Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health of Healthcare Workers–A Perception of Indian Hospital Administrators

Faculty of Public Health, Poornima University, Jaipur, 303905, India

* Corresponding Author: Anahita Ali. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(7), 833-845. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.028799

Received 07 January 2023; Accepted 20 February 2023; Issue published 01 June 2023

Abstract

Since the coronavirus pandemic, many factors led to the change in the mental well-being of hospital administrators and their staff. The pandemic negatively impacted the availability and capability of health professionals to deliver essential services and meet rising demand. Therefore, this study aimed to understand the perspective of hospital administrators about issues and challenges that negatively impacted their staff’s mental health and hospital administrators’ coping response to mitigate those challenges and issues. An exploratory qualitative study was conducted with 17 hospital administrators (superintendents, deputy superintendents, nursing in charge and hospital in charge) working in a government district hospital of Rajasthan state during September 2022 and October 2022. This study revealed various emerging themes on mental health-related issues, challenges and coping strategies reported by the administrators. Themes and sub-themes that emerged from this study were 1) Perceived mental health of HCWs-perceived importance of mental health, 2) Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of HCWs– common mental health issues, changes in mental health pre and post-pandemic, 3) Impact of COVID-19 on health behavior of HCWs-increased self-care and awareness, 4) Challenges responsible for poor mental health of HCWs-organizational, ethical and societal challenges and 5) Strategies to retain mental health of HCWs-effective coping strategies. The most common problems were increased levels of stress, feeling fatigued, tiredness, weak and anxiety among the HCWs. Keeping their staff motivated was the biggest challenge reported. Social support, counseling through professionals and demystifying myths were the most effective coping strategies adopted by the participants. In conclusion, this study reported poor mental health-related issues, challenges faced by the HCWs and effective strategies adopted by hospital administrators during tough situations. This study will assist hospital administrators in developing interventions such as regular training programs and workshops to teach effective coping skills to address poor mental health during crises.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

After 2 years of coronavirus (COVID-19), the pandemic is still not over. This pandemic has not only influenced all aspects of human health but also the human lifestyle [1]. Workers in the healthcare sector have emerged as the key workforce in the battle against this pandemic. The most important factor is their safety and well-being because they are not only responsible for constant patient outcomes but also maintain and control infection as they work in the hospital [2].

Mental health issues are disorders or illnesses that affect the mood, way of thinking and behavior of a person. According to research, frontline HCWs are more prone to experience mental health problems like anxiety, depression, sleeplessness, and stress globally [3]. The pandemic negatively impacted the availability and capability of health professionals to deliver essential services and meet rising demand [4]. Many factors led to the change in the mental well-being of health professionals including hospital administrators and their staff. These factors may act as an independent source of stress (commonly called stressors) during emergencies. For instance, limited availability and affordability of hospital resources including personal safety equipment (PPE), face masks, gowns, respirators, poor infrastructure, incomplete guidelines on patient handling and many others. During the COVID-19 second wave in India, the country faced the maximum number of mortalities and morbidities. These resources (potential stressors for HCWs) were in short supply in the majority of healthcare institutions including India [5,6]. HCWs in India claimed that prolonged usage of personal protective equipment (PPE) is to account for both work and social challenges [7]. Previous studies suggest that due to higher-than-usual demand for these resources made them re-use PPEs, masks and gowns for many days in hospitals which affected their health and posed an increased risk of getting COVID-19 infection [8]. Also, the HCWs were responsible to look after both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 infected patients admitted in the hospitals which demonstrated the unfair distribution of work responsibilities-another risk factor for stress. In terms of infrastructural resources, the HCWs found the rapid change of wards into isolation rooms to be a source of stress [9].

Healthcare organizations are responsible to provide safe working environments. These are complicated structures that function in a hierarchy. In these organizations such as hospitals, HCWs need managers above them who can provide leadership and supervision to manage their staff at all levels. Hospital managers are important decision-makers also. These decisions not only ensure perfect healthcare service delivery to the patients but also the health and well-being of the workers who work under them. Unfortunately, there is limited literature on the studies that focused on the perception of Indian hospital administrators during the COVID-19 pandemic including issues reported to them by their staff, challenges they faced such as shortage of PPE, lack of hospital space, unclear guidelines and the effective strategies adopted by them to retain their staff’s mental health. Additionally, there is a scarcity of literature on how Indian hospital administrators perceive their staff’s mental health and its importance during public crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Most studies have focused on the experiences of Indian frontline HCWs such as nurses and doctors who handled and treated COVID-19-infected patients through a quantitative approach while the qualitative approach is used in limited studies. The qualitative approach gives the opportunity to keep the study design flexible, make assumptions and develop hypotheses for testing through a quantitative approach. Because we aimed to conduct a quantitative study simultaneously (for data triangulation and hypothesis testing), we used a qualitative approach in this study to gain a deeper understanding.

Given the gaps above, to understand the perception of hospital administrators about staff’s mental health, issues and challenges within the context of an organization, it is important to know what are the workplace challenges, mental health-related issues reported to the Indian hospital administrators during a public health crisis and effective coping strategies adopted to address the emerging problems. Therefore, the objective of this study was to understand the perspective of hospital administrators on mental health issues, challenges that negatively impacted their staff’s mental health and their coping response to mitigate those challenges and issues.

An exploratory qualitative study was conducted to understand the perspective of hospital administrators about mental health issues, challenges that negatively impacted their staff’s mental health and their coping response to mitigate those challenges and issues.

Therefore, we included hospital administrators (superintendents, deputy superintendents, nursing in charge and hospital in charge) working in a government district hospital in Rajasthan state from September 2022 to October 2022. Face-to-face semi-structured interviews in the English language were conducted with every participant that lasted for 35–40 min. This hospital is situated in a northwestern district of the Indian state with the second highest population in the state, which is approximately 3.6 crores. It also has 24 government healthcare facilities which are the highest in the state. The district hospital provides a tertiary-level healthcare services where approximately 3000 healthcare staff is employed of which 20 administrators handle the facilities. The different departments include cardiology, neurosurgery, cardiothoracic, gastroenterology and many others.

Study participants and selection

The study participants for the study were all the hospital administrators employed in the district hospital such as the superintendent, deputy superintendent, nursing in charge and hospital in charge. Because of the small number of administrative staff (n = 20), we included all of them in our study. By applying non-probability purposive sampling, all those who were available during the time of the interview and gave their consent to participate in the study were included.

The participants were approached and interviewed as per their availability. Those who were not available during the time of interview and could not be contacted after three attempts were excluded from the study. Of total 20 administrators, 17 administrators participated voluntarily in the study. There were eight male and nine female participants. No compensation or incentive was given to the participants. Face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted with the participants in the English language during which, the initial 5 min were spent on the introduction of the researcher, information about the study (purpose, aim and methods), related risks and benefits of participating in the study, verbal consent for participation and audio taping using a digital voice recorder. The interviews took place in the respective chambers (dedicated hospital administration office) of the participants. To ensure that their chamber was quiet and has no external noise or disturbances during the interview, patients and other hospital employees were not allowed to come inside during the interview. To maintain privacy, only participants were present in their respective chambers during the interview. The entry gate was guarded by their assistants and security guards to avoid interruption. After receiving the consent, the interview was initiated by asking demographic data such as name, age, designation, marital status, education level and experience level from the participants. The researcher also took field notes during the interview to note down all the important points. The interviews were ceased based on pragmatic grounds as we achieved theme completeness because themes were replicated indicating a completeness level rather than a theoretical saturation level.

The interview protocols were developed and revised after testing [10]. The interview protocol was narrowed down to three sections namely issues reported, challenges faced during the COVID-19 pandemic that affected the mental-health of staff and coping strategies adopted to mitigate the challenges and issues. It contained open-ended questions related to the three sections as mentioned. The key questions were developed before the study but the interview format was kept flexible to add or change questions according to the interview. Questions about common issues and challenges such as “challenges in work life since COVID-19 pandemic, challenges faced at organizational, individual and societal levels” [8,11,12] and coping strategies were asked based on the Brief–COPE Inventory. It is a condensed version of Carver’s COPE scale [13]. These questions were also part of the mixed method study (quantitative part). The key questions were the following:

“How important is the mental health of your staff in this hospital?”

“What were the common mental health related issues that your staff reported to you?”

“Since the COVID-19 pandemic, what were the various mental health related challenges that your staff have faced at work?”

“How did you handle or still handle those issues and challenges at managerial level?”

“What were the coping strategies adopted by you as a leader/manager to manage the mental well-being of the staff?”

Data analysis and quality control

As the interviews were audiotaped, the first researcher transcribed verbatim into English language and transferred it to ATLAS.ti version 22 software for analysis. Further, the analysis was done using an inductive approach in which both researchers independently read the transcripts to identify emerging themes and codes. Firstly, a framework for the codebook was developed that helped to code all the transcripts. Secondly, the notes made by the first researcher during the interview were also summarized. Thirdly, both researchers read the transcripts repeatedly to identify more themes and sub-themes. Finally, to address the similarities and differences that emerged from the coding done by both researchers independently, both of them discussed the themes and agreed on the best-representing data to fulfill this study’s purpose.

To ensure the validity of this study, a quantitative method was conducted simultaneously to compare the results. The results of the quantitative study are published separately. To ensure comprehensive reporting of the qualitative results, consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist of sampling method, data collection, analysis, description of themes and supporting quotations was followed [14].

Both the researchers that conducted this study were experts in the public health field. The first researcher was a female Ph.D. student and she conducted the interviews. She has previous experience in conducting qualitative research. The second researcher was a male Professor with Ph.D. in hospital administration. He supervised all the steps in this study, contributed to study proposal development, interview guide development, data coding, theme development and final approval of this paper. Because he also works as a hospital director in a private hospital, his experience of facing potential issues and challenges faced during public health crises as an administrator helped to develop interview questions relevant to the study purpose. No relationship with the participants was established before the commencement of the study. The participants were informed about the researcher’s personal goal and reason for doing the research.

The ethical clearance was obtained from the ethics committee of the tertiary hospital and university. The participants gave their verbal consent for voluntary participation. All participants were made aware that taking part in the interview was completely voluntary, they were free to withdraw at any moment, their answers will only be used for publication purposes and their identities will remain confidential. Additionally, respondents were notified that in the event of unpleasant sentiments, they might seek a psychological assistance service. The interviews were recorded and then transcribed.

This study was conducted in accordance with Institutional Review Board approval (JSPH-IRB/2022/06/26) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of S.N. Medical College (SNMC/IEC/2022/618 dated 18/08/2022). Informed verbal consent was obtained from the study participants.

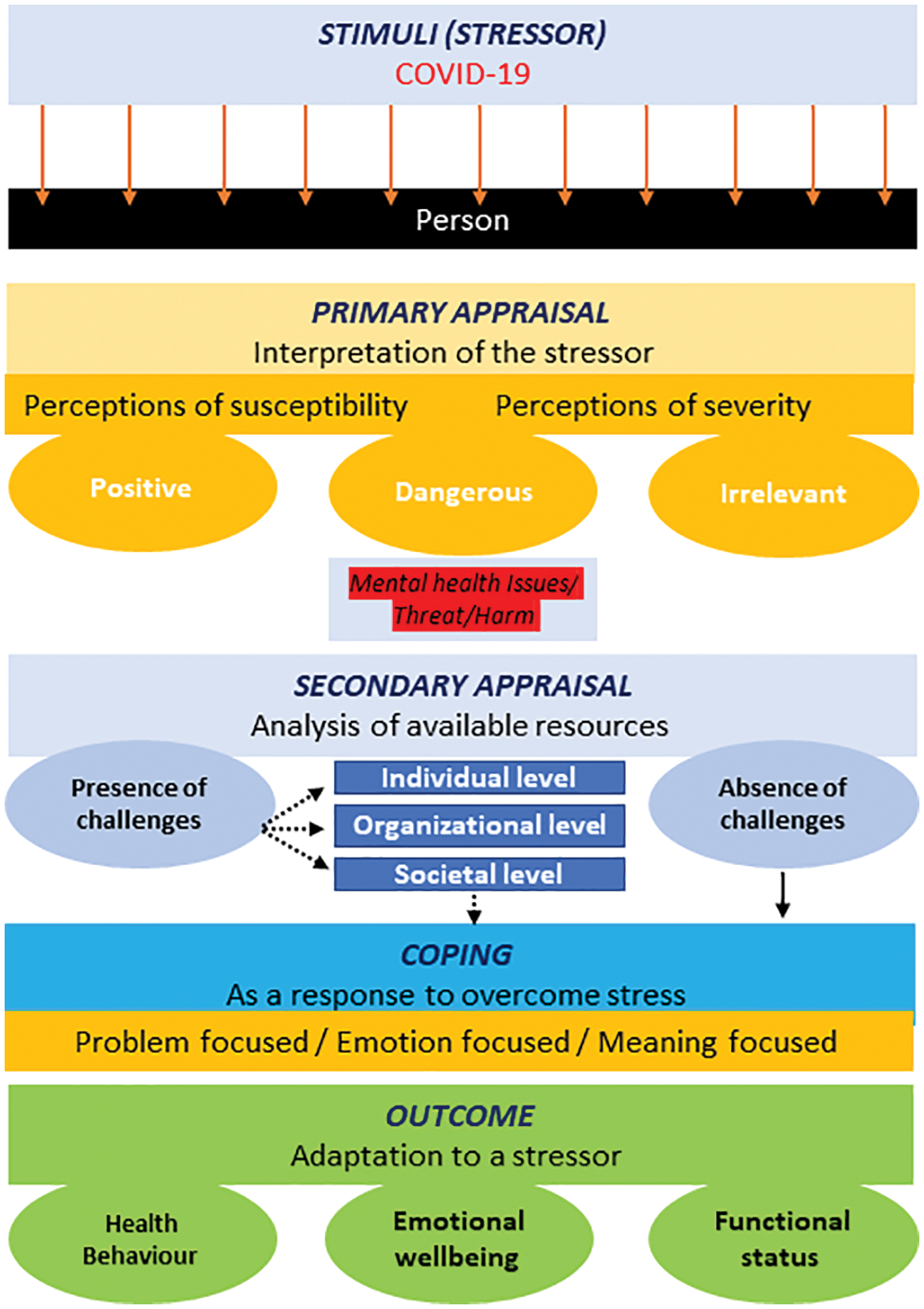

The coping strategies used by people who are diseased or at risk of getting the disease may influence their overall health. Amid stress, support from friends and family can have a profound effect on cognitive and emotional outcomes. Previous research has focused on the risks and extenuating circumstances associated with trauma and stress-related disorders. Currently, there is a lack of understanding of the risk factors and stressors that contribute the most to psychological distress in people [15]. Furthermore, knowing this theory on stress and coping is critical for nurses and healthcare providers to design effective techniques and approaches to improve coping and promote physical, mental, and somatic well-being, the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping [16] may prove to be a helpful framework for examining coping processes with stressful occurrences in this study.

Fig. 1 below illustrates the adoption of the transactional model of stress and coping in the current study. As some people may feel the high intensity of the stressor while others may not get much disturbed by it. The effect of the stressor on a person decides the adoption of the primary appraisal. Few people may continue to feel threatened and that their life is in danger while others may feel that they are safe and are not as vulnerable to the virus as others during the COVID-19 pandemic. The possible reasons for these variations in the perceived susceptibility and severity are age group, socio-economic status, designation, and other demographic characteristics. These factors may act as a challenge and add stress to the situation. The mutual stress caused by the situation itself and the challenges led to the adoption of a coping strategy to reduce the overall stress. Furthermore, challenges faced at different levels (individual, organizational and societal) may act as a challenge to mental health and affect coping behavior. The positive coping strategy adoption may show up as enhanced emotional well-being, positive change in health behavior, or positive change in health status while the negative or no coping strategy adoption may deteriorate the mental health of the HCWs (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Adapted transactional model of stress and coping.

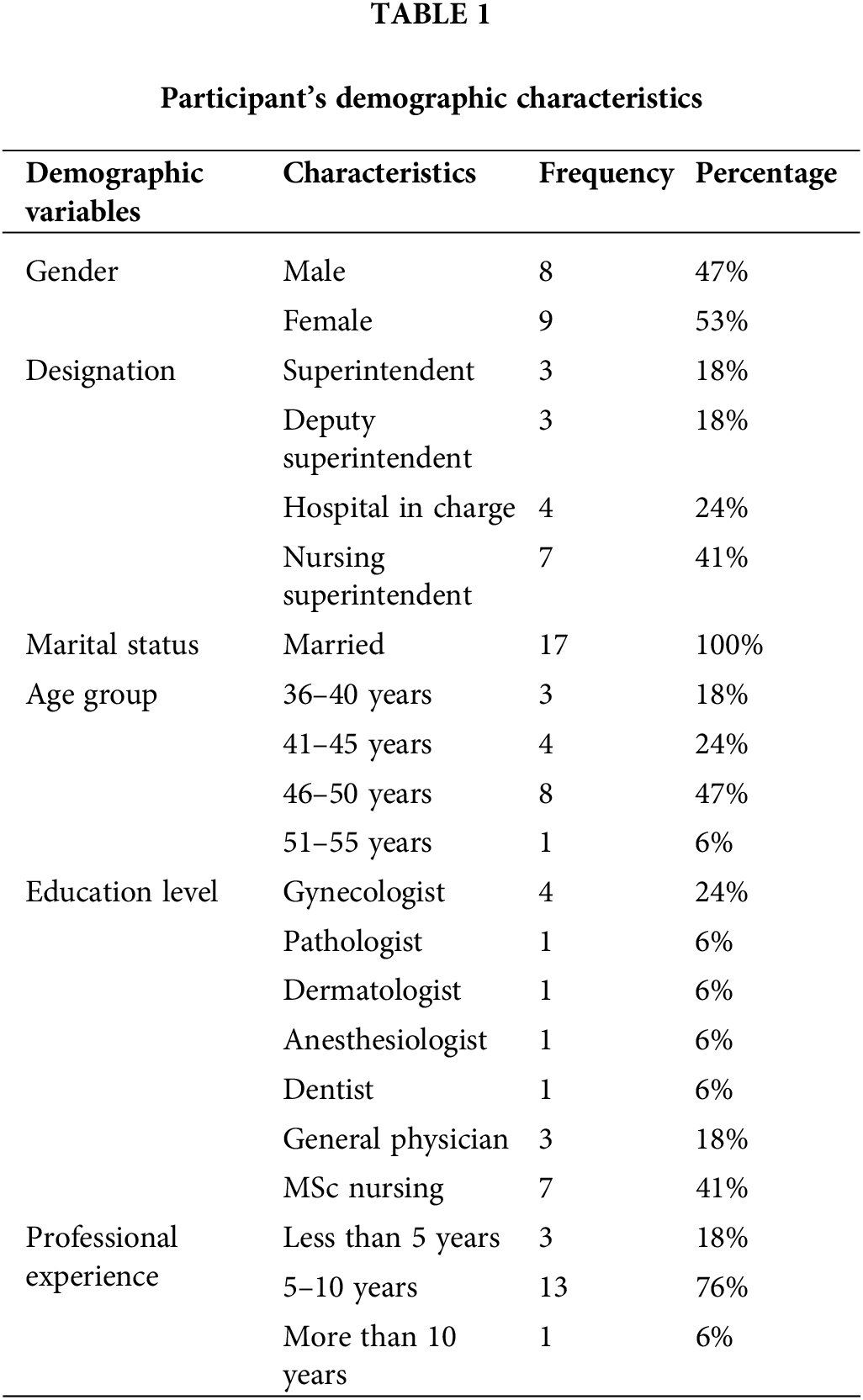

Of the 17 participants, 8 (47%) were male and 9 (53%) were female (see Table 1). The mean age was 45 years and 48 years for women and men, respectively.

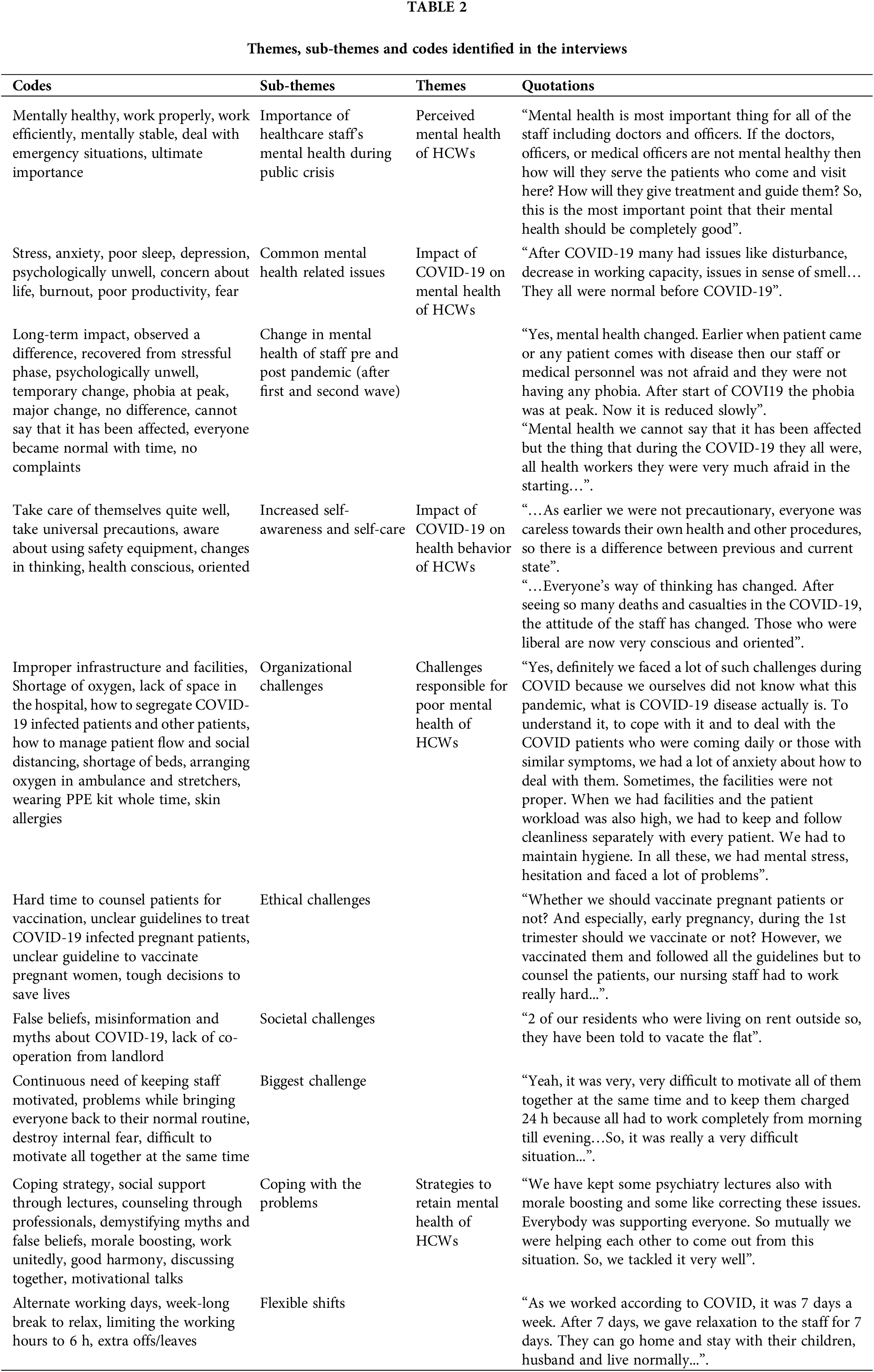

The following section discusses different themes that emerged from this study–1) Perceived mental health of HCWs, 2) Impact of COVID-19 on mental health of HCWs, 3) Impact of COVID-19 on health behavior of HCWs, 4) Challenges responsible for poor mental health of HCWs, 5) Strategies to retain mental health of HCWs. The sub-themes, codes and main themes supported by quotations are given in Table 2.

Theme 1: Perceived mental health of HCWs

Sub Theme 1: Importance of healthcare staff’s mental health during public crisis

All the participants perceived mental health of their healthcare staff important as they mentioned that the complete well-being of their staff, including mental and physical health is important to treat the patients. Additionally, they accepted the importance of mental health while handling emergencies and patients. Altogether, they agreed that the overall fitness of the HCWs is important to work efficiently in the hospital.

“Mental health is important for all of us, the nursing staff because if we are not mentally prepared or mentally stable then how will we treat the patients. We have to deal with emergency situations also; we have to cope up with the patients also. So, it is very important to have proper mental health.” (Respondent 2, nursing in charge).

Theme 2: Impact of COVID-19 on mental health of HCWs

Sub Theme 1: Common mental health related issues

A few participants experienced a positive change in their relationship with their staff. They felt their staff is like their second family due to which their staff is quite open to sharing their problems with them. The staff did not hesitate to share the issues they faced since the COVID-19 pandemic. This changed relationship helped the administrators to manage their staff’s mental health. However, they accepted that the COVID-19 pandemic created stress in everyone’s life.

“Definitely COVID has affected them a lot. Because everybody knows that the COVID pandemic was real stress to life also. So even though they were the frontline warriors, and they were fighting day-night with the disease in helping the patients to come out from the disease, definitely that has affected them also.” (Respondent 3, superintendent).

According to the administrators, the most common problems were the increased levels of stress and anxiety among their staff. Some HCWs felt physical stress such as felt fatigue, tiredness and weak. Being afraid of getting COVID-19 infection was commonly reported by them. The participants mentioned that their staff was scared of getting infected as they were concerned for the safety of their families and close relatives and they could have spread the infection to them.

“The staff was very much scared, and they were all afraid of the infection. And especially, overall, they had this fear that because of them, the family might suffer. They all were so afraid. And all the time, they had the fear factor in their mind that because of patients, either they would catch the infection or because of themselves being healthcare workers, they might go and give infection to the family and friends.” (Respondent 5, hospital in charge).

Skin allergies from wearing masks, PPE kits for long duration such as up to 12 h were also reported by the HCWs.

“They faced difficulties that they could not get time for even for tea or water. Whole time they were working while wearing masks and PPE kit. So, it was very hard and they were all wet from inside due to the heat. I myself have seen that some had skin allergies because of wearing PPE kit the whole time. They did wear masks for 12–13 h, due to the triple layer mask their skin got marks. So, they faced such kinds of problems.” (Respondent 15, superintendent).

A participant experienced a difference in the stress levels of the staff as a high number of young female workers and those who had children reported more stress than male workers.

“Here I had noticed that females do have more stress and in females particularly young females, child bearing females. Many times, the duty assigned to them is night in COVID time. They were fearful of infection so they used to come and report us.” (Respondent 15, superintendent).

Sub Theme 2: Change in mental health of staff pre and post pandemic (after first and second wave)

Most participants accepted that the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the mental state of their staff. Some participants observed a difference in mental well-being pre-pandemic and post-pandemic indicating the negative impact of COVID-19. According to them, most of their staff had recovered from their stressful phase; however, some were still suffering from the long-term impact of this pandemic.

“As recently, the COVID-19 phase has passed, there was no problem before it. After this, some people became COVID-19 positive, some were not but still they are psychologically unwell, they are in tension.” (Respondent 4, nursing in charge).

“After COVID many had issues like disturbance, decrease in working capacity, issues in sense of smell, problem in breathing and some of them even got diabetes problems. They were hypertensive. They all were normal before COVID.” (Respondent 7, nursing in charge).

Theme 3: Impact of COVID-19 on health behavior of HCWs

Sub Theme 1: Increased self-awareness and self-care

Interestingly, some participants revealed the other side of the COVID-19 pandemic as they experienced a positive difference in their staff’s behavior pre and post-pandemic. They observed increased self-awareness among their staff. This has changed the self-care behavior of the HCWs in a positive manner. However, some participants mentioned no long-term effect of the pandemic.

“Yes definitely, there is a visible difference. As earlier we were not precautionary, everyone was careless towards their own health and other procedures, so there is a difference between previous and current state.” (Respondent 2, nursing in charge).

“Yes, the mental state has changed a lot. Everyone’s way of thinking has changed. After seeing so many deaths and casualties in the COVID, the attitude of the staff has changed. Those who were liberal are now very conscious and oriented.” (Respondent 17, deputy superintendent).

Theme 4: Challenges responsible for poor mental health of HCWs

Sub Theme 1: Organizational challenges

Managing a team of HCWs effectively who work at several levels is a challenging task in itself. In this study, the participants experienced a sudden occurrence of the COVID-19 disease that resulted in organizational challenges they faced while managing their teams such as a lack of facilities, preparedness, a sudden increase in the flow of patients and many others. This created a challenge for the HCWs’ mental health.

“Yes, definitely we faced a lot of such challenges during COVID because we ourselves did not know what this pandemic, what is COVID-19 disease actually is. To understand it, to cope with it and to deal with the COVID patients who were coming daily or those with similar symptoms, we had a lot of anxiety about how to deal with them. Sometimes, the facilities were not proper. When we had facilities and the patient workload was also high, we had to keep and follow cleanliness separately with every patient. We had to maintain hygiene. In all these, we had mental stress, hesitation and faced a lot of problems.” (Respondent 2, nursing in charge).

Because the participants reported a high flow of patients in their hospitals, it created a lack of space to manage the flow and at the same time had to follow social distancing. One participant experienced a challenge while segregating the COVID-19-infected and non-COVID-19-infected patients in the outpatient department (OPD).

“At an organizational level, the biggest problem was how to segregate the patients who visit here, who are COVID infected and who are not. However, we bought temperature checking machines and arranged a staff nurse outside so that they can check the temperature of patients who enter here. All those whose temperature is not appropriate; they will be segregated. So, we faced a problem in this segregation.” (Respondent 17, deputy superintendent).

One participant in the present study shared an experience struggling to save the lives of those who were in immediate need of oxygen beds in their hospital. Due to the shortage of beds, they arranged stretchers and ambulances to give oxygen and saved them. A few participants experienced challenges due to the shortage of supplies in the initial phase. Shortage of oxygen and beds was commonly reported as the participants shared their struggles while arranging the supplies.

“We had this challenge to provide oxygen and a bed to anyone coming to the hospital. But in one situation, for some days we kept two patients on one bed. There was a situation where we kept oxygen on a stretcher. We kept one device that could provide oxygen to five patients from one cylinder. We did that too. So, when one patient comes, we attach the tube through a server and device. Be it a patient on a stretcher or bed, we kept two patients on one bed by keeping “T” on bed. We had managed this. Many times, it happened that a patient came by 108 ambulances, so we had to go there and give them oxygen because we didn’t have a bed.” (Respondent 15, superintendent).

“Back then at the time of COVID we didn’t have availability of oxygen immediately. Then we had to manage at our personal level to avail oxygen from here and there. We managed at our personal capacity to get oxygen at earliest. If oxygen is available at that time, then the patient can be cured soon.” (Respondent 9, deputy superintendent).

Sub Theme 2: Ethical challenges

The participants experienced some ethical challenges while dealing with the patients and their families during the pandemic. As mentioned, some participants felt the concern for their patients such as maintaining distance while checking the patient. Some participants reported stressful situations where they had to take tough decisions in light of their ethical responsibility as an HCW. They also expressed their concern that those decisions were hard to explain to the patient but were important for their sake.

“Yeah, sometimes patients used to have that thing in mind that the doctors are not touching them. The doctors are examining them from very far off. So, they used to really feel very bad also that earlier we used to check up very nicely and by touching it, used to spent time for us but now it feels like we are tied with strings and then they used to feel bad also that we are making them sit a little far away from us and we are not touching them and examining them that was really a little painful situation for the patients.” (Respondent 5, hospital in charge).

After the introduction of a vaccine against the corona virus, hospital administrators experienced unique ethical challenges in vaccinating pregnant women, lactating mothers and many others. Initially, they were not informed about the safety of the vaccine for pregnant women and its effect on their fetus. Therefore, their staff faced problems while handling such patients and their families in the hospital and were not able to answer their queries.

“Whether we should vaccinate pregnant patients or not? And especially, early pregnancy, during the 1st trimester should we vaccinate or not? However, we vaccinated them and followed all the guidelines but to counsel the patients, our nursing staff had to work really hard to decide whether COVID vaccine should be given during pregnancy or not.” (Respondent 17, deputy superintendent).

A participant in this study observed a sudden increase in the abortion rates because of the lack of information about the adverse effect of COVID-19-positive pregnant women on their fetuses. Due to this, women terminated their early pregnancies.

“Here we had many early pregnancy cases who had abortions at increased level. Early abortion rates increased during COVID time. In some cases, those who became COVID positive, their mother, attendant became very conscious that she is COVID positive and has early pregnancy, the child will be defective. This factor was dominating a lot and they were all in trouble as they used to ask us thousands of questions. And during that time, guidelines were also not available. There were many cases who used to come and ask us whether we should terminate it or not? This was a major ethical issue.” (Respondent 17, deputy superintendent).

Many times, the HCWs face ethical dilemmas where they have to take tough decisions to save the life of the patient. A similar challenge was experienced by the participants of this study where they took some risks to save the patient regardless of the COVID-19 infection status of the patient.

“Many times, it did happen that a patient came all of a sudden and due to change in duty, the staff is changing dress, wearing gloves but then patients come in an emergency and they have to rush out without taking precautions to save the patient.” (Respondent 15, superintendent).

Sub Theme 3: Societal challenges

Some participants experienced challenges from society due to misinformation and myths attached with to COVID-19 pandemic. The false beliefs created a problem for their staff to work efficiently and affected their mental well-being. Seeing the other side, the participants experienced a sense of responsibility and serving the community by staying away from social gatherings to break the chain of transmission.

“People nearby, they are all afraid, oh, she’s a doctor, she might give us infection, and she might spread it. So, it is better to stay a little far off from her. And in society also, I also used to feel if I’m meeting my elders or my relatives, so I should stay a little away from them, I should wear proper masks, I should keep myself protected. Because of me, they are not infected, because I was meeting almost 100 to 200 people per day.” (Respondent 5, hospital in charge).

“2 of our residents who were living on rent outside so, they have been told to vacate the flat.” (Respondent 11, hospital in charge).

However, most participants did not experience any challenges from their society or local community. Rather, they expressed their society’s positive support towards them.

Sub Theme 4: Biggest challenge

The participants perceived various challenges as their biggest challenge. A few of them expressed the continuous need of keeping their staff motivated was the biggest challenge. They faced problems while bringing everyone back to their normal routine of work.

“The biggest thing was to make everyone understand, although everyone is well trained and well qualified that the effect of COVID-19 has become less so we should now follow our normal routine. The main thing was to destroy the internal fear among people and start a normal routine again. This was the only challenge that now most of the officers and workers have understood and have become normal also.” (Respondent 12, hospital in charge).

“Yeah, it was very, very difficult to motivate all of them together at the same time and to keep them charged 24 h because all had to work completely from morning till evening. And anytime they could be called for any work. So, it was really a very difficult situation and a very big challenge and tasks to keep them motivated 24 by 7.” (Respondent 8, hospital in charge).

Interestingly, some participants agreed that during this pandemic they were well prepared in terms of physical and mental state and had sufficient resources such as personal protective kits, masks, and others to handle the situation. Preparing in advance helped them to maintain a good mental state of their staff during the second wave.

“At that time, I was in charge of COVID-19 ward. So, we have to take care of everything including the manpower, their allotment and the disease. Yes, it came very suddenly. So, there was very less time for preparedness as in the first wave but in the second wave we are well prepared. Although, the mortality was high but still on part of the mental level so, for the first we have, we don’t have much time, but for the second wave we have managed things very well.” (Respondent 3, superintendent).

Theme 5: Strategies to retain mental health of HCWs

Sub Theme 1: Coping with the problems

As the participants experienced different problems and challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, not having a common coping strategy helped all of them deal with the problem. Rather, different strategies helped them to manage their staff within their hospitals. In general, social support through lectures, counseling through professionals and demystifying myths and false beliefs were the most effective coping strategies adopted by the participants.

“We have kept some psychiatry lectures also with morale boosting and some like correcting these issues. Everybody was supporting everyone. So mutually we were helping each other to come out from this situation. So, we tackled it very well.” (Respondent 3, superintendent).

“Discussing together and motivating each other such as motivational talks and motivational stories that we shared with each other. And the biggest thing was our unity. Our unity helped us all to cope up.” (Respondent 2, nursing in charge).

Some participants organized their staff’s work shifts by giving them alternate working days in the hospital while some provided a week-long break to relax. Additionally, limiting the working hours to 6 h also helped them to relieve the stress of their staff.

“For this, the workers have a routine duty. We don’t keep the duty continuously. For example, they had 7 days continuous duty then we made changes after 3 or 4 days” (Respondent 4, nursing in charge).

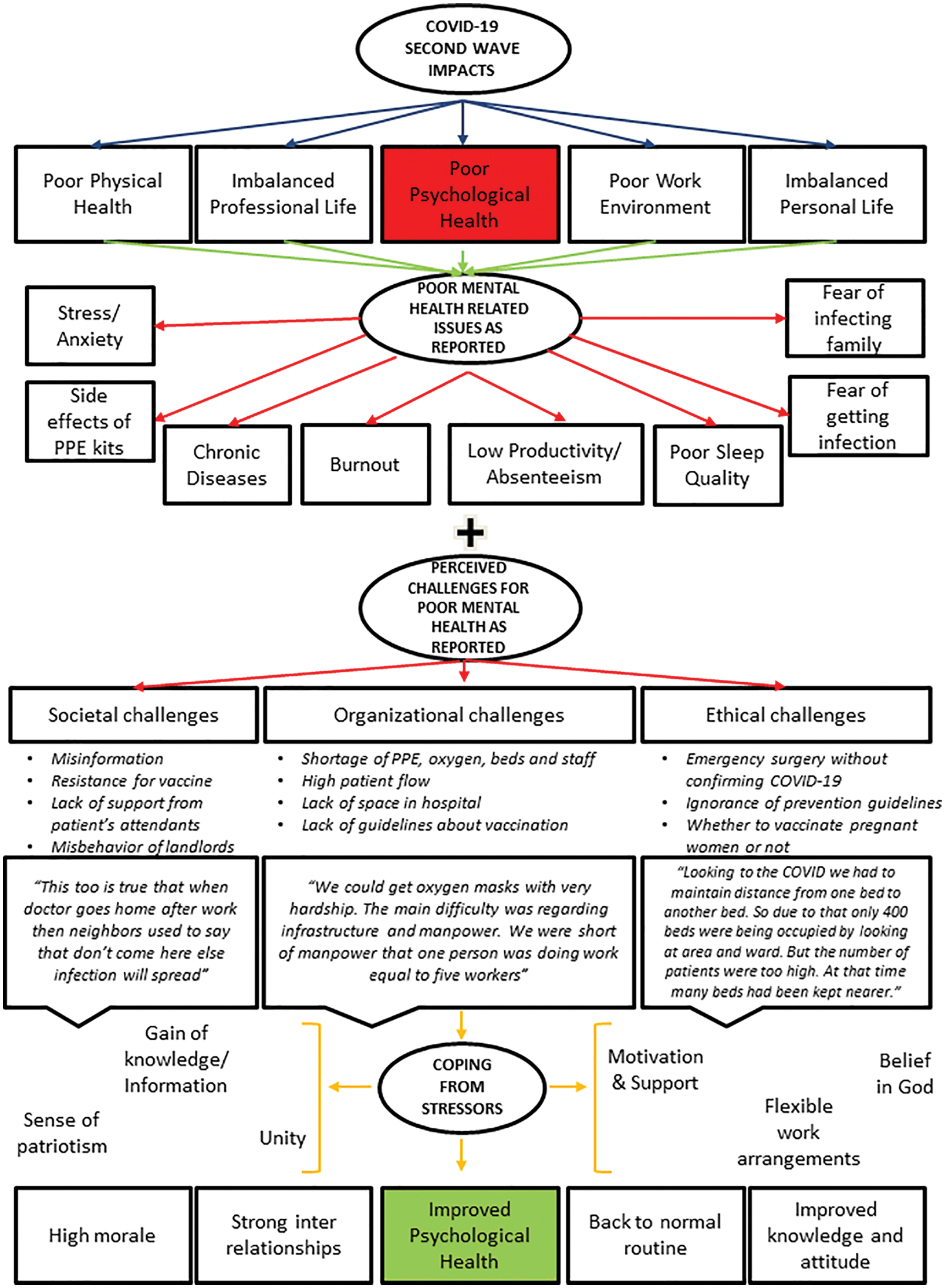

Fig. 2 below provides a summary of how COVID-19 pandemic impacted HCWs in India and resulted in poor physical health, a stressful work environment, imbalanced professional and personal life and poor psychological well-being. This study focused on COVID-19 pandemic impacts on mental well-being in response to which, several issues were reported by the HCWs to their respective hospital administrators such as increased stress, anxiety, burnout, skin infections, uncomfortable while wearing PPE kits for a long time, poor sleep quality due to increased working hours, less productivity and fear of getting COVID-19 infection. They also faced challenges at different levels such as personal, organizational and societal levels that increased their work stress during the COVID-19 pandemic and resulted in poor mental health. Altogether, in response to the issues reported to the hospital administrators by their staff and the challenges faced by them, a few coping strategies were effective handling the stressful situation and retaining good mental health. These coping strategies were more centered towards emotion-focused coping such as motivation and peer support to the staff on an everyday basis, working with unity, demystifying COVID-19 pandemic-related myths with the help of appropriate information and arranging flexible shifts for the staff. These strategies, in turn, resulted in the improved mental well-being of the HCWs, high morale for the work, improved relationships with the hospital administrators and improved attitude and self-awareness (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Summary of the emerging themes.

This qualitative study aimed to understand the perspective of hospital administrators about issues and challenges that negatively affected their staff’s mental health and their coping response to mitigate those challenges and issues. The participants reported that stress, anxiety, poor sleep and fear of getting COVID-19 infection were common issues reported to them. Their staff faced challenges at different levels that resulted in poor mental health such as shortage of PPE, long working hours, improper guidelines, disbalance in professional and personal life and many others. To address these problems, the participants adopted a few strategies that helped them manage their staff effectively such as motivation, counseling, a sense of serving and others. Overall, it was overserved that the participants used a combination of emotion-focused and problem-focused coping strategies to retain their staff’s mental health.

Previous studies suggest disrupted psychological well-being due to various factors such as poor sleep quality, nature of work and many more among the HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic [17–22]. The results of the present study are suggestive of similar risk factors and common stressors that may alter the psychological well-being of the health workforce during a crisis or biological disaster. Good mental health at the workplace is of utmost importance as demonstrated in this study [23]. History suggests the negative impacts of an outbreak, epidemic, or even a pandemic on the HCWs’ mental health. A qualitative study conducted with the HCWs of Sierra Leone during the 2014 Ebola outbreak reported fear of getting the infection, breakdown, increased stress at work and many more [24]. These mental health issues are in line with those reported by the participants in the present study. Similar issues were also reported by the nursing officers during the ongoing first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in India including mental and emotional distress at work [2]. A questionnaire-based study among the frontline HCWs across India reported increased levels of stress, anxiety and nervousness [21,25] which were also reported by the participants in this study. The qualitative approach of this study helped obtain a deeper understanding of the potential risk factors, stressors and reasons for poor mental health. The quantitative study designs in previous studies may lack this deeper understanding and have presented the issues superficially. On the other side, the findings of this study are in line with nurses from Iran that stated their concerns about living in a state of uncertainty because they were afraid of becoming infected [26]. Similar studies suggest that young healthcare professionals [27] and those working in clinical departments [12] have higher stress levels, anxiety, and depression than their senior coworkers and those in non-clinical departments [28]. Contrastingly, a participant experienced higher stress levels reported by female HCWs than their male staff. Altogether, all these factors are likely to lead to burnout among HCWs as evidenced by the emotional exhaustion, detachment, and feeling of worthlessness stated by HCWs in China [29]. In general, this study found that a few demographic characteristics such as being female and having children may act as risk factors for increased stress at work during crises, suggesting the influencing role of gender on anxiety and coping which was not frequently reported in previous studies [30].

Regardless of being a frontline HCW in a developed economy or developing economy, the COVID-19 pandemic has equally affected them across the globe. This study demonstrates the importance of appropriate infrastructural facilities, complete disaster or emergency preparedness and many other important resources, a shortage of which, may act as risk factors and challenges for poor mental health among the workers. Many HCWs from previous studies reported similar challenges [5,24,31] that negatively impacted their mental health. For instance, those from the UK during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic reported a lack of personal protective kits and guidance as a common challenge [5]. The participants also faced challenges with the limited availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) at the workplace which was commonly reported in the present study [3,32–35]. Similar experiences with the shortage of PPE have made working in the healthcare industry the most challenging time [33,36,37]. Due to the higher-than-usual demand for PPE and an inability to provide it, healthcare personnel was under unusual pressure to re-use their PPEs for many days [32]. All these challenges are in line with the present study and strengthen the existing supporting literature. Following the appropriate resources for good mental health, comes ethics-related practice in the professional lives of HCWs on an everyday basis. Unfortunately, during the COVID-19 pandemic, these ethical practices were compromised to save the lives of the patients. For instance, participants in this study experienced a hard time while taking instant decisions such as handling patients without getting their COVID-19 positive report, attending patients in an emergency without PPE and many others. These decisions were taken as part of their moral duty to serve the people during an emergency. These experiences of the ethical dilemma are in line with nurses from various hospitals around the globe during the COVID-19 pandemic who faced ethical challenges while serving patients with limited resources [12,28,38]. In general, this study emphasizes the need for appropriate resources such as proper infrastructure, complete guidelines and many others. This study also provides evidence that a shortage of these resources may act as a risk factor for the poor mental health of HCWs during crises.

Coping with mental health issues such as stress or a stressful situation is important to achieve complete well-being. For instance, dealing with a sudden flow of patients while maintaining their mental health was challenging for HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. With the highest mortality rates in India during the second wave, the COVID-19 pandemic was a big challenge for frontline workers to cope with this phase. This study demonstrates the importance of coping skills of HCWs as well as the effective strategies of hospital administrators, reflecting a sense of leadership needed to cope with stressful situations. The participants in this study shared their strategies that were effective to retain the mental health of HCWs. The combination of problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies such as regular use of sanitizers, online lectures to provide complete information and motivation and moral support proved to be effective in maintaining the good mental health of the HCWs in the present study. These findings are in line with a similar study conducted with the HCWs during the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone who used social media platforms to stay connected with their team and spread the information [24]. However, on the other side, nurses of a tertiary hospital in India used only emotion focused strategies such as the use of mobile phones and watching serials to relax during the COVID-19 pandemic [2] while those from China reported seeking support and active planning as their coping style [39].

Finally, on a positive note, this study demonstrates a positive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of the improved relationship of hospital administrators with their staff, self-awareness, self-care and changing health behavior among the HCWs. The participants in this study considered their staff as their family, sat together, discussed issues during the pandemic and even celebrated together as a part of the motivation to work. Similar acts were reported by the nurse managers and their assistants who reported professional support as an important factor in to fight against the COVID-19 pandemic [40]. The results from the present study suggest that in light of professional development, the participants in the present study experienced a change in the behavior of their staff as they became more aware of their health and served the patients with increased self-confidence levels than before. The nurse managers of other countries who served during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, reported a sense of development as they gained strength in their profession and personal development which is in line with the present study [28,32,41,42]. In general, this study emphasizes the importance of healthy interprofessional relationships to address the complete well-being of professionals in the workplace.

There is scarce literature that reports the perception of hospital administrators in terms of poor mental health-related issues reported to them, challenges faced by their staff and coping strategies adopted by them to retain the mental health of their staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the original findings of this study will guide hospital administrators by demonstrating the negative impact of a public crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. As reported in this study, the healthcare staff was given online lectures and counseling through professionals such as psychiatrists, it is evident that there is a need for organizing regular training and workshops to enhance the coping skills of hospital administrators and their staff to help them deal with stress during emergencies. This study will provide scientific pieces of evidence by equipping hospital administrators with a variety of issues, challenges and evolving best and effective strategies as reported in this study. Finally, this will guide the administrators to plan interventions to prevent poor mental health among the HCWs in the organizations such as teaching cognitive behavior therapy and mindfulness techniques that are feasible because improving the well-being of the health workforce will directly improve the quality of the nation’s healthcare system.

This study has some strengths and limitations. Firstly, the qualitative approach in this study allowed the investigators to explore the issues and challenges at different levels that negatively impacted the mental health of their staff. It allowed gaining a deeper understanding of the problems and effective strategies to retain mental health at the workplace during crises such as COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this study will provide strong evidence for the quantitative study which was carried out simultaneously. Secondly, as the participants in this study were working at different designations in different hospitals, they gave broad insights into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, it is the only study of its kind conducted with government district hospital administrators. As a limitation, firstly, getting in touch with the hospital administrators was difficult as they stay loaded with their roles and responsibilities. A lot of follow-ups were done to get their consent and availability for the interviews. This resulted in limited access to the participants. Secondly, this study was retrospective in nature and questions were related to past perceptions and experiences. It may have induced recall bias as the participants may have forgotten or missed important information to share. Finally, the perceived issues and challenges reported to the hospital administrators may have faded with time because this study was conducted after the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, the coping behavior may change with time. As reported in this study, most of the HCWs had temporary mental health-related issues that resolved with time, therefore, this study may not have captured the true perceptions of the administrators being retrospective in design.

History reveals many biological disasters such as H1N1, SARS, Spanish flu and others that came into existence and impacted human health quite strongly but the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is the highest to date. HCWs all over the world were put in a unique situation where they had to make difficult decisions and work under pressure as the virus spread. Many health systems were taken off guard by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to anxiety and uncertainty in the battle against it. This study reported poor mental health-related issues, challenges faced by the HCWs and effective strategies adopted by hospital administrators during tough situations. Unusual from other diseases, the COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges that added to the worse mental health of the HCWs at organizational, individual and societal levels. This study suggests developing interventions such as regular training programs and workshops to teach effective coping skills to address poor mental health during crises.

Acknowledgement: We thank all the participants of this study for their participation.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: AA., SK.; data collection: AA.; analysis and interpretation of results: AA., SK.; draft manuscript preparation: AA. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data is available on request from the corresponding author and is not available publicly.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dyer O. COVID-19: Omicron is causing more infections but fewer hospital admissions than delta, South African data show. BMJ [Internet]. 2021;375:n3104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n3104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Kalal N, Kumar A, Rani R, Suthar N, Vyas H, Choudhar V. Qualitative study on the psychological experience of nursing officers caring COVID 19 patients. Indian J Psy Nsg [Internet]. 2021;18:2–7. [Google Scholar]

3. Golechha M, Bohra T, Patel M, Khetrapal S. Healthcare worker resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study of primary care providers in India. World Med Health Policy [Internet]. 2022 Mar 1;14(1):6–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Nyashanu M, Pfende F, Ekpenyong M. Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J Interprof Care [Internet]. 2020;34(5):655–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1792425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Bhatia S, Pal S, Saha D. Challenges faced by community health workers in COVID-19 containment efforts [Internet]. 2021. https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/human-development/challenges-faced-by-community-health-workers-in-covid-19-containment-efforts.html. [Google Scholar]

6. Viplav V. Health Care Workers are facing several challenges during COVID-19 pandemic: Times of India [Internet]. 2020. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/readersblog/newspost/health-care-workers-are-facing-several-challenges-during-covid-19-pandemic-dr-prof-raju-vaishya-11529/. [Google Scholar]

7. Dang P, Grover N, Srivastava P, Chahal S, Aggarwal A, Dhiman V, et al. A qualitative study of the psychological experiences of health care workers during the COVID 19 pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021;37(1):93–97. [Google Scholar]

8. Sengupta M, Roy A, Ganguly A, Baishya K, Chakrabarti S, Mukhopadhyay I. Challenges encountered by healthcare providers in COVID-19 times: an exploratory study. J Health Manag [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1;23(2):339–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/09720634211011695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tapas C, Beena ET, Simran K, Rony M, Geetha RM, Murugesan P, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in India & their perceptions on the way forward-a qualitative study. J Dent Educ [Internet]. 2012;76(11):1532–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23144490. [Google Scholar]

10. Jacob S, Furgerson S. Writing interview protocols and conducting interviews: tips for students new to the field of qualitative research. The Qualitative Report [Internet]. 2015;17(42):1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2012.1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Vejdani M, Foji S, Jamili S, Salehabadi R, Adel A, Ebnehoseini Z, et al. Challenges faced by nurses while caring for COVID-19 patients: a qualitative study. J Educ Health Promot [Internet]. 2021 Nov 1;10(1):423–30. [Google Scholar]

12. Sperling D. Ethical dilemmas, perceived risk, and motivation among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Ethics [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1;28(1):9–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020956376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub KJ. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol [Internet]. 1989;56(2):267–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQa 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care [Internet]. 2007 Dec;19(6):349–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Agha S. Mental well-being and association of the four factors coping structure model: a perspective of people living in lockdown during COVID-19. Ethics Med Public Health [Internet]. 2021;16(2):100605. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemep.2020.100605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Mccauley M, Minsky S, Viswanath K. The H1N1 pandemic: media frames, stigmatization and coping. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2013;13(1):1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Gupta B, Sharma V, Kumar N, Mahajan A. Anxiety and sleep disturbances among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in India: cross-sectional online survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill [Internet]. 2020 Oct 1;6(4):e24206. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/24206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Parthasarathy R, TS J, K T, Murthy P. Mental health issues among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic–a study from India. Asian J Psychiatr [Internet]. 2021 Apr 1;58(3):102626. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Al-TA, Johnson J, Biyani CS, Connor DO. Psychological and occupational impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK surgeons: a qualitative investigation. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2021;11(4):e045699. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Raven J, Wurie H, Witter S. Health workers’ experiences of coping with the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone’s health system: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2018;18(251):1–9. [Google Scholar]

21. Mulla R, Gopalaswamy V, Saini R, Vajipeyajula A, Santosh K, Thimmarayappa VMK. Prevalence of stress and associated changes in the personal habits of frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: a questionnaire based study. Int J Health and Clin Res [Internet]. 2021;4(4):169–77. [Google Scholar]

22. Baloran ET. Knowledge, attitudes, anxiety, and coping strategies of students during COVID-19 pandemic. J Loss Trauma [Internet]. 2020;25(8):635–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1769300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Søvold LE, Naslund JA, Kousoulis AA, Saxena S, Qoronfleh MW, Grobler C, et al. Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: an urgent global public health priority. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 May 7;9:679397. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.679397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Babore A, Lombardi L, Viceconti ML, Pignataro S, Marino V, Crudele M, et al. Psychological effects of the COVID-2019 pandemic: perceived stress and coping strategies among healthcare professionals. Psychiatry Res [Internet]. 2020 Jan;293(7):113366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Skapinakis P, Bellos S, Oikonomou A, Dimitriadis G, Gkikas P, Perdikari E, et al. Depression and its relationship with coping strategies and illness perceptions during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece: a cross-sectional survey of the population. Depress Res Treat [Internet]. 2020;2020:1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3158954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Bijani M, Karimi S, Khaleghi A, Gholampoor Y, Fereidouni Z. Exploring senior managers’ perceptions of the COVID-19 Crisis in Iran: a qualitative content analysis study. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1;21(1):1071. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07108-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Razu SR, Yasmin T, Arif TB, Islam MS, Islam SMS, Gesesew HA, et al. Challenges faced by healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative inquiry from bangladesh. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Aug 10;9:e831. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.647315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Jia Y, Chen O, Xiao Z, Xiao J, Bian J, Jia H. Nurses’ ethical challenges caring for people with COVID-19: a qualitative study. Nurs Ethics [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1;28(1):33–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020944453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Sam CP, Mamat NH, Nadarajah VD. An exploratory study on the challenges faced and coping strategies used by preclinical medical students during the COVID-19 crisis. Korean J Med Educ [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1;34(2):95–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2022.222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Li L, Ai H, Gao L, Zhou H, Liu X, Zhang Z, et al. Moderating effects of coping on work stress and job performance for nurses in tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2017 Jun 12;17(1):401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2348-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Waselewski EA, Waselewski ME, Chang T. Needs and coping behaviors of youth in the U.S. during COVID-19. J Adolesc Health [Internet]. 2020:67:649–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

32. Koontalay A, Suksatan W, Prabsangob K, Sadang JM. Healthcare workers’ burdens during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative systematic review. J Multidiscip Healthc [Internet]. 2021;14:3015–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

33. Specht K, Primdahl J, Jensen HI, Elkjær M, Hoffmann E, Boye LK, et al. Frontline nurses’ experiences of working in a COVID-19 ward–a qualitative study. Nurs Open [Internet]. 2021;8(6):3006–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Al-Ruzzieh M, Ayaad O. Work stress, coping strategies, and health-related quality of life among nurses at an international specialized cancer center. Asian Pac J Cancer P [Internet]. 2021 Sep 1;22(9):2995–3004. doi:https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.9.2995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hayat K, Arshed M, Fiaz I, Afreen U, Khan FU, Khan TA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study from Pakistan. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Apr 26;9:3345. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.603602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Huang L, Lei W, Xu F, Liu H, Yu L. Emotional responses and coping strategies in nurses and nursing students during COVID-19 outbreak: a comparative study. PLoS One [Internet]. 2020;15(8):1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. White JH. A phenomenological study of nurse managers’ and assistant nurse managers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. J Nurs Manag [Internet]. 2021 Sep 1;29(6):1525–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Gebreheat G, Teame H. Ethical challenges of nurses in COVID-19 pandemic: integrative review. J Multidiscip Healthc [Internet]. 2021;14:1029–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

39. Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, Guo Q, Wang XQ, Liu S, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2020;8(6):e790–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hølge-Hazelton B, Kjerholt M, Rosted E, Hansen ST, Borre LZ, McCormack B. Improving person-centred leadership: a qualitative study of ward managers’ experiences during the COVID-19 crisis. Risk Manag Healthc Policy [Internet]. 2021;14:1401–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S300648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Ness MM, Saylor J, di Fusco LA, Evans K. Healthcare providers’ challenges during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: a qualitative approach. Nurs Health Sci [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1;23(2):389–397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Deldar K, Froutan R, Ebadi A. Nurse managers’ perceptions and experiences during the COVID-19 crisis: a qualitative study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res [Internet]. 2021 May 1;26(3):238–44. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools