Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Experiences of Counselors Who Provided Psychological Support during COVID-19 Disaster: A Qualitative Study

1

Namgu Mental Health Welfare Center, Daegu, 42424, South Korea

2

Department of Nursing, Kyungil University, Gyeongbuk, 38428, South Korea

* Corresponding Author: So Yeon Yoo. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(5), 687-697. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.026759

Received 24 September 2022; Accepted 20 December 2022; Issue published 28 April 2023

Abstract

Background: In crisis intervention sites such as infectious disease disasters, counselors are repeatedly exposed, directly or indirectly, to the traumatic experiences of victims. Disaster counseling has a negative effect on counselors, which can eventually interfere with the counseling process for disaster victims. Therefore, exploring and understanding the experiences of counselors is necessary to ensure that qualitative counseling for disaster victims can be continuously and efficiently conducted. Objectives: This study investigated the experiences of counselors who participated in mental health counseling as psychological support for victims of the COVID-19 disaster in Korea. Design: This is a qualitative study. Participants: The study participants comprised 18 counselors who had mental health professional qualifications of level 2 or higher and who had provided mental health counseling for COVID-19 confirmed cases and quarantined persons. Methods: Data were collected using focus group interviews from February 21 to May 29, 2021. The duration of each interview was 60–90 min, and the data were analyzed using content analysis. Results: The final theme was “Continuing to walk this road anytime, anywhere.” The participants’ experiences were identified in four sub-themes: “being deployed to unprepared counseling,” “encountering various difficulties,” “feeling full of meaning and value,” and “hoping to become a better counselor.” Conclusions: In order to continuously provide qualitative counseling in case of an infectious disease disaster such as COVID-19, it is important to develop a qualification and competency strengthening program through education and training to secure the crisis intervention expertise of counselors according to the characteristics of the disaster. In addition, a psychological support manual for each disaster should be prepared at the national level according to the type of disaster.Keywords

Infectious disease disasters such as the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which is still spreading worldwide, cause not only physical damage but also extreme stressful situations [1–4]. The outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015 also caused anxiety and fear among many Koreans, and 70.8% of the confirmed patients had psychiatric problems such as depression, insomnia, tension, aggression, memory loss, and auditory hallucinations [5]. According to a 2021 survey that examined the mental health outcomes of COVID-19 in Korea, 55% of the respondents complained of anxiety and depression due to COVID-19, and the severity of the symptoms increased with increasing age [6]. The stress level during COVID-19 was 1.5 times that of MERS and 1.4 times that of the Gyeongju and Pohang earthquakes, which was higher than that of the Sewol ferry disaster [4].

As these mental health problems affect not only persons afflicted with infectious diseases but also the people around them and the local community [7], efforts to alleviate their psychological pain are necessary. According to the National Mental Health Survey in Korea, half of the people expressed their desire to receive mental health counseling services in relation to COVID-19 [6]. As such, the importance of counseling and the role of counselors are being emphasized to respond sensitively to the needs of those afflicted during infectious disease disasters. Counseling plays an important role in minimizing psychological pain and damage and promoting mental health.

The counseling process with victims of disasters, including infectious diseases, greatly impacts counselors as well. In crisis intervention sites such as earthquakes and fires, counselors are repeatedly directly or indirectly exposed to the traumatic experiences of victims during the counseling process [8]. This negatively affects counselors, engendering symptoms such as fatigue and loss of vitality [8]. Moreover, in cases where they are unable to help disaster victims, an added sense of guilt has a serious emotional impact on counselors [9]. Disaster counselors often experience symptoms similar to those experienced by disaster victims [10], such as nightmares and fears, and experience physical and emotional exhaustion [11]. Exhausted counselors may gradually become indifferent to caring for disaster victims [12]. This can happen when counselors empathize and focus on the emotional difficulties of victims, eventually hindering counseling for disaster victims [13].

Therefore, continuous provision of qualitative counseling is necessary to improve the psychiatric health of disaster victims. To this end, counselors’ experiences during the counseling process must be understood and efforts to prevent the exhaustion of counseling manpower should be promoted. In the case of city D in Korea, where many coronavirus infections occurred in a short period of time in early 2020, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation were higher than the overall average in Korea; among them, the rate of reporting suicidal ideations was particularly high [14,15]. This qualitative study examines the experiences of counselors who participated in mental health counseling for confirmed COVID-19 patients and quarantined persons in Korea’s city D. It aims to determine the essence of the meaning experienced by counselors in the course of counseling and to understand how these experiences affect their lives. The study results intend to provide basic data to organize a program to prevent the exhaustion of counselors and promote their growth in the event of infectious disease disasters such as COVID-19.

This study is a qualitative research that applies the focus group interview method to explore and understand the experiences of counselors who consulted COVID-19 confirmed patients and quarantined persons by phone.

The study participants comprised 18 counselors (13 women and 5 men) who were members of the Integrated Psychological Support Group in city D and had a mental health professional certificate of level 2 or higher. Participants were mental health professionals at an intermediate or higher level, and had acquired first and second grade certificates. They had expertise and skills in the field of mental health, had received training from an institution prescribed by the Ordinance of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and had been recognized by the Minister of Health and Welfare of Korea. To recruit participants, the purpose of the study was explained to the Integrated Psychological Support Group officials. They were requested to recommend suitable participants for the study and a notice was posted on the bulletin board. The snowball technique was used for participant recruitment. The purpose, methods, and ethical considerations of the study were explained to the interested candidates and interviews were conducted with those who agreed to participate. The interview was conducted in an easeful atmosphere and could be stopped at any time upon the participants’ request without any disadvantage. The criterion sampling method, which is mainly used in qualitative research, was used to select participants. It comprises two aspects: relevance and sufficiency. Relevance refers to selecting participants who can provide the best information about the research topic, and sufficiency refers to collecting data until saturation is reached for a sufficient and rich explanation of the research phenomenon. The number of participants was thus finally determined when the data saturation point of this study was reached [16]; that is, until no new information was found. The participant inclusion criteria comprised counselors who had conducted phone consultations for psychological support of COVID-19 confirmed patients and quarantined people and those who could communicate and understand the purpose of this study. The exclusion criteria were being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder or treated for an acute illness and requesting withdrawal from the study.

2.3 Data Collection and Procedure

The data were collected from February 21 to May 29, 2021. Six focus group interviews were conducted with each group consisting of two to four persons. One researcher with qualitative research experience conducted the interviews, each lasting 60–90 min, which were recorded.

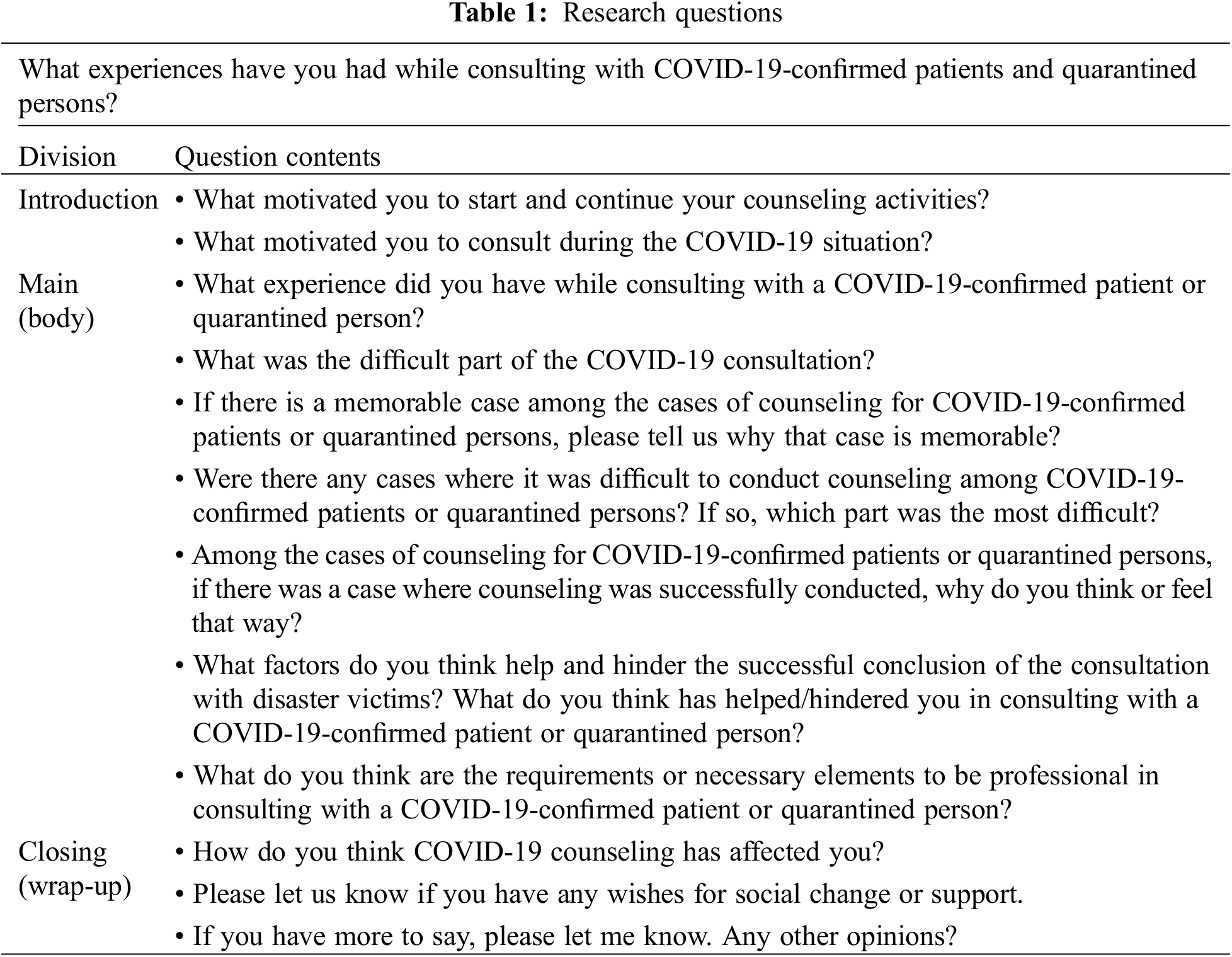

The focus group interviews used semi-structured questionnaires consisting of introduction, main questions, and closing questions regarding the experiences and changes during counseling activities for COVID-19 confirmed and quarantined patients (Table 1). During the interview, the researcher listened to the participants’ statements and encouraged them to express their experiences as abundantly as possible, recording the themes, main points, non-verbal content (expressions, gestures, etc.) and atmosphere. The recorded contents were transcribed immediately, and the contents were repeatedly analyzed while reading and listening for the vocabulary and intensity of emotions used by the participants.

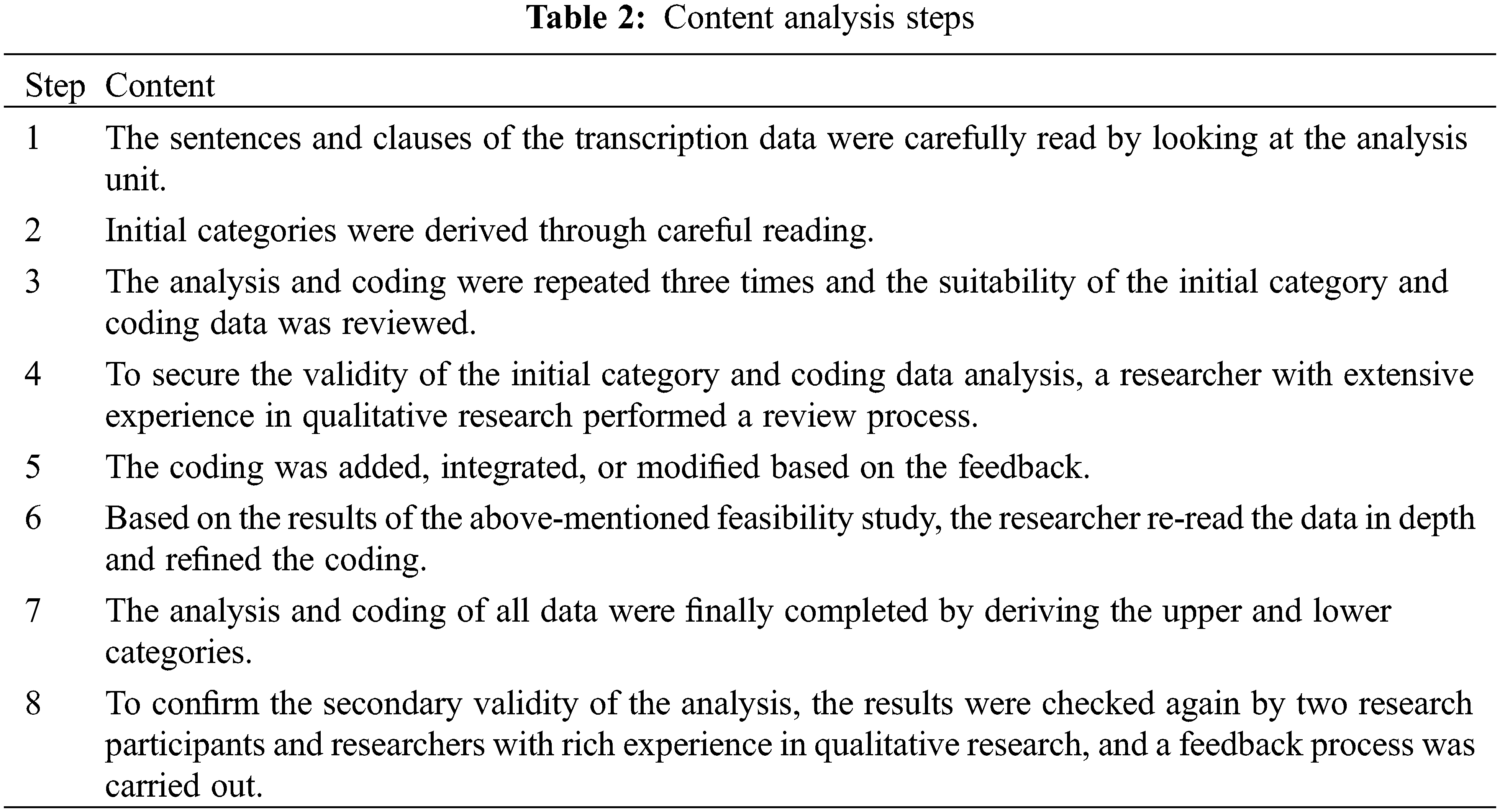

Data analysis was conducted simultaneously with data collection using Downe-Wamboldt’s [17] eight steps of content analysis to derive essential themes from the counselors’ experiences. The detailed analysis process is shown in Table 2. After no further content was found in the analysis result, the analysis was terminated. The content analysis findings were evaluated according to the criteria for reliability, applicability, auditability, and neutrality [18]. To ensure reliability, three study participants confirmed the data used in the analysis and the results obtained. The applicability of the study results was confirmed by two counselors who had experience consulting with COVID-19-confirmed patients or quarantined persons, but did not participate in the study. Two researchers with extensive research experience in the field of qualitative research were consulted regarding the procedure and research results of this study to ensure auditability. Finally, neutrality was secured by comparing the conclusions of this study with previous studies.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kyungil University (1041459–202012-HR-004-01) in Korea. All participants signed a written consent form, indicating their willingness to participate voluntarily. The researcher assured the participants that the data would be used for research purposes only and that confidentiality would be ensured by not including identifiable information about the participants in the interview data. It was also explained that the data identifying the participants and the consent forms would be deleted after being securely stored for three years after the end of the study without Internet/password access.

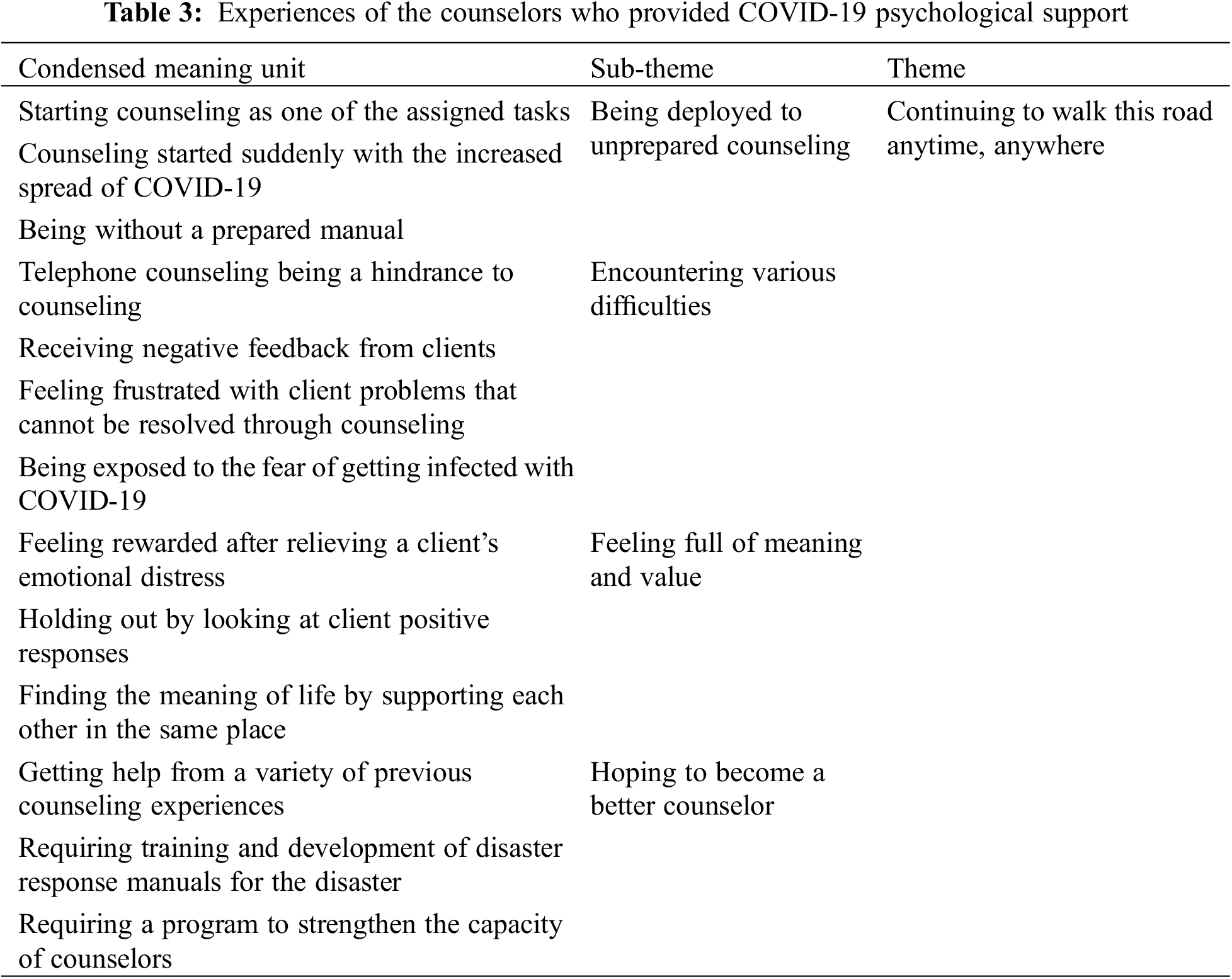

The participants were between 28 and 55 (average 40) years old, had worked as a counselor for 6 to 156 months (average 66 months), and had 1 to 13 months’ (average 10 months) experience as a counselor for COVID-19 patients. From the 13 condensed meaning units that were derived from the analysis of the counselors’ experiences, four sub-themes and one overall theme were identified. The four sub-themes were ‘being deployed to unprepared counseling,’ ‘encountering various difficulties,’ ‘feeling full of meaning and value’ and ‘hoping to become a better counselor,’ and the final theme was ‘Continuing to walk this road anytime, anywhere’ (Table 3).

3.1 Sub-Theme 1: Being Deployed to Unprepared Counseling

Counselors said that when they were deployed to provided psychological support to COVID-19 clients after the outbreak of the pandemic, they were embarrassed that no specific manual had been prepared for it.

“I am working at the D Metropolitan Mental Health Welfare Center, so as COVID-19 spread in D city, I participated because I heard that I had to do psychological support, so I joined.” (Counselor 14)

“At that time, basic information related to COVID-19 was changed from time to time and the response method was also changed. If I guide you through this uncertain information, there was confusion, so it was difficult to proceed with the counselling. It would have been nice if there was a manual for responding to basic COVID-19 information, or an information sharing system.” (Counselor 2)

3.2 Sub-Theme 2: Encountering Various Difficulties

Participants experienced various difficulties while conducting psychological counseling with COVID-19 clients. Counseling over the phone hindered the counseling process. Counselors received negative feedback from clients and felt frustrated by problems that could not be solved by counseling. Moreover, the counselors were in a situation where they were exposed to the fear of getting infected.

“Since it was a phone consultation, it was difficult to consult if I could not hear well. When counseling, an environment for counseling should be created, but if the surrounding environment is not created, it seems to interfere with the counseling process.” (Counselor 1)

“Since it is telephone counseling rather than face-to-face counseling, I thought that I needed skills and competency to conduct telephone consultations because I had to understand the person’s inner intentions, desires, emotional state, etc., only through the voice.” (Counselor 2)

“There are people who unconditionally get angry with the counselor and say negative things. In this case, when the counselor could not resolve these feelings, it seems that it was difficult not only to consult with the person but also to proceed with the next counseling.” (Counselor 3)

“This part was very difficult because we could not directly help physically, and there were administrative limitations that could not help the situation of those infected with COVID-19.” (Counselor 13)

“As COVID-19 continues and is prolonged, the number of confirmed cases continues to increase, even today emergency disaster text message alerts are ringing from time to time on mobile phones. During the phone consultation, several people were confirmed with COVID-19, and I suffered from anxiety that I might have overlapped the movements with those confirmed patients.” (Counselor 7)

“As I am also a human being, I think I always worked nervously at the thought of not knowing when and how I might get infected. I’ve been in counseling for a long time, but I think it’s the first time I’ve been scared while doing counseling.” (Counselor 4)

3.3 Sub-Theme 3: Feeling Full of Meaning and Value

Counselors realized the value and meaning of the counseling and psychological support they provided when they saw client emotions get resolved and when clients expressed their gratitude to them. This allowed them to hold on to the difficult position of a counselor.

“The most rewarding thing is when the client’s anxiety is lowered through counseling, so the client says ‘thank you’ to me.” (Counselor 11)

“I wondered if this counseling would be worthwhile. Nevertheless, when I listened to the client’s difficulties and received direct feedback saying that the client problem has been resolved, I thought, “Oh, it’s still meaningful for us to counsel on the phone.” (Counselor 2)

3.4 Sub-Theme 4: Hoping to Become a Better Counselor

When the counselors were asked to provide COVID-19 counseling without preparation, their previous experiences helped significantly during the consultations. Therefore, it was emphasized that programs to strengthen the capacity of counselors, including education and the development of response manuals for each disaster, need to be developed and applied to ensure better counseling in the future.

“I have experienced clinical psychology at the hospital, I have consulted at the National Mental Hospital, and have done the counseling for MERS, humidifier damage, disasters, and wildfires. So, the things that came out of those experiences helped me a lot when I was consulting with people who were affected by this coronavirus. Also, since I am in my 50 s, I think I was able to form a consensus well thanks to the experience gained in previous years.” (Counselor 8)

“During the counseling, I realized that I needed to continue training and felt the need to study. I think it is necessary to study and gain experience to strengthen your competencies.” (Counselor 10)

“It seems that I have been thinking a lot about wanting to develop my own capabilities. I hope there will be many opportunities to develop my capabilities. Even if I want to improve my capabilities, I am sad that there are not many places like that.” (Counselor 16)

3.5 Theme: Continuing to Walk This Road Anytime, Anywhere

Although the participants were tasked with providing counseling without much preparation and experienced various difficulties, they hoped to do better as they recalled the rewards and meanings associated with their work. Accordingly, in the future, they could be suddenly deployed for counseling during similar difficult situations but they hope to continue doing their work.

“There were many difficult moments, but there were also people who said thank you for the help, so I thought that was the driving force that made me endure, and I think it was the opportunity to continue counseling.” (Counselor 5)

In this study, four sub-themes were derived from the experiences of counselors who consulted with COVID-19 confirmed patients and quarantined persons. The first and second sub-themes were “being deployed to unprepared counseling” and “encountering various difficulties,” respectively. After the first COVID-19 confirmed case in Korea, the number of confirmed and quarantined cases rapidly increased in city D, and counselors were urgently deployed to the COVID-19 crisis intervention sites. The study participants stated that at the time of the intervention, all citizens of city D availed themselves of counseling and most counselors consulted with COVID-19 confirmed cases, quarantined persons, and their families. The participants had worked as community mental health counselors and received education on suicide prevention and mental health; they were unfamiliar with crisis intervention counseling in infectious disease disaster situations such as COVID-19. In addition, they felt a lot of anxiety, uncertainty, and pressure regarding whether they were properly prepared as experts. This is similar to the results of a previous study in which counselors who participated in the Ferry Sewol disaster counseling experienced anxiety, fear, and hopelessness about whether they could adequately play the role of counselors [19]. The participants of this study said that city D was enveloped in a fearful atmosphere and the confirmed and quarantined people complained of extreme anxiety and fear. In particular, counselors experienced feelings of frustration and helplessness because they could not provide practical help to clients who complained of physical pain or difficulty in breathing due to high fever and severe cough. Since most of the counselors were residents of city D, they became empathetic toward the distressed clients. Previous studies have demonstrated that while counseling patients who have experienced trauma, counselors also experience considerable stress and vicarious trauma just by listening to the pain and difficulties of clients [3,20]. Several studies have reported that counselors’ feelings are involved while empathizing with the sadness or pain of clients [9,21] and that continuous counseling and empathy with distressed clients negatively affect counselors’ personal lives [22]. Therefore, it is necessary to provide programs to prevent exhaustion and vicarious trauma of counselors assigned in disaster crises intervention such as COVID-19.

According to Ursano et al. [23], the most demanded psychosocial support in the event of a disaster is to ensure that disaster victims are safely protected and provided with food and medical supplies. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, research participants in city D experienced more exhaustion because they could not address the priority needs of the victims as they had to provide psychological support for them. In the event of a disaster, physical and psychological support should be provided simultaneously with disaster-related information [23,24]. The study participants pointed out that the major problems comprised a lack of disaster counseling specialists, inadequate administrative support system, and the absence of a non-face-to-face response manual. This is consistent with the experiences of mental health experts who have participated in disaster and crisis interventions [25]. In the United States, the support contents and roles of each organization in the event of a disaster are specified by law and the disaster-related service delivery system has been compiled into a manual, enabling prompt and appropriate response [26,27]. However, in Korea, the National Trauma Center was opened in 2018 but the legal system for crisis intervention or psychological support activities in the event of a disaster is still insufficient. Therefore, it is necessary to prepare specific policy alternatives to respond quickly and appropriately in the event of an infectious disease disaster in Korea.

The third and fourth sub-themes were “feeling full of meaning and value” and “hoping to become a better counselor.” Although counselors faced many difficulties in the process of crisis intervention during COVID-19, they felt rewarded after watching clients resolve their negative emotions through counseling. This not only became a source of strength to endure the difficulties but also motivated counselors to improve counseling by upgrading their qualifications and capabilities. In a disaster situation, the network of relationships between people becomes more vulnerable [28]. In such cases, counseling for disaster crisis intervention helps clients overcome or cope with psychological difficulties. It can be inferred that the support provided by counselors and the relationships formed with clients contributed to the psychological stability and healing of clients during the COVID-19 crisis intervention counseling process. In addition, the counselors supported and depended on their fellow counselors when they were exhausted and this helped them significantly with the counseling. This result is in line with other studies on counselors who participated in crisis intervention in disaster situations [29,30]. This suggests that encouragement and support among counselors is important in the counseling process for disaster crisis intervention as it helps them grow as counselors and demonstrate self-efficacy. Furthermore, countries and institutions should not only endeavor to create environments where counselors can manage themselves on a regular basis, but also design specific programs or systems that provide appropriate psychological support to counselors, to help them continue counseling healthily.

The study participants emphasized that the disaster counseling experience helped them reflect on their lives and provided an opportunity to think about the competencies and qualities required for counselors participating in crisis intervention. They looked back on their lives and experienced insight and growth as a counselor. This is similar to the research results of Lee et al. [19]. Therefore, it can be said that the counselors have undergone post-traumatic growth [31], which refers to a change that occurs in people who have directly or indirectly experienced various traumatic events.

Psychological first aid is important for disaster victims, which is different from traditional counseling methods [32]. The participants’ previous experiences of counseling people with severe mental illness and suicidal tendencies in the local community were helpful in the COVID-19 crisis intervention counseling process. However, crisis intervention at the disaster site is an important activity for the healing of clients and since disaster counseling is different from the traditional counseling methods, it is necessary to have a response manual according to the type of disaster and a separate professional education. Therefore, counselors’ qualifications and competency must be strengthened through education and training to secure their expertise in crisis intervention according to the characteristics of disasters, and at the national level, a psychological support manual and professional manpower training process are required for each disaster.

The results of this study evidence the need for research on the development and application of psychological support guides specific to the ongoing crisis, and competency enhancement programs for counselors. However, this study has some limitations. This study was conducted during the first half of 2020, when psychological support for COVID-19 was being actively provided, rather than when the provision of this support ended. Additionally, the study involved counselors who were active in a specific region where a large number of COVID-19 infections occurred in a short period of time. Hence, caution should be exercised while generalizing the findings. Nevertheless, these limitations can be attenuated as this study derived in-depth results through focus group discussions and documents the actual experiences of counselors.

This study examined the experiences of counseling personnel for psychological support with COVID-19 through a qualitative research method and the four sub-themes that emerged were integrated under the theme “Continuing to walk this road anytime, anywhere.” The results of this study can be used as basic data to educate and strengthen counseling personnel so that the exhaustion caused by difficult circumstances can be prevented and high-quality psychological support and counseling can be provided to those in crisis due to infectious disease disasters.

Funding Statement: This study was conducted with support from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021R1I1A3052264).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kim, S. B., Choi, T. Y., Kim, J. W., Yoon, S. Y., Won, G. H. et al. (2022). The psychological impact of quarantine during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Journal of the Korean Society of Biological Therapies in Psychiatry, 28(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.22802/jksbtp.2022.28.1.27 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Buliva, E., Elhakim, M., Tran Minh, N. N., Elkholy, A., Mala, P. et al. (2017). Emerging and reemerging diseases in the World Health Organization (WHO) Eastern Mediterranean Region-progress, challenges, and WHO initiatives. Frontiers in Public Health, 19(5), 276. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00276 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Trippany, R. L., Kress, V. E. W., Wilcoxon, S. A. (2004). Preventing vicarious trauma: What counselors should know when working with trauma survivors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00283.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Park, J. E., Kang, S., Won, S., Roh, D., Kim, W. (2015). Assessment instruments for disaster behavioral health. Anxiety and Mood, 11(2), 91–105. [Google Scholar]

5. Shin, J., Park, H. Y., Kim, J. L., Lee, J. J., Lee, H. et al. (2019). Psychiatric morbidity of survivors one year after the outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in Korea, 2015. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, 58(3), 245–251. https://doi.org/10.4306/jknpa.2019.58.3.245 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lee, E., Kim, W. (2021). A study on the effect of the infectious disease disaster on the mental health due to COVID-19. Gyeonggi: Gyeonggi Research Institute. https://www.gri.re.kr/web/contents/resreport.do?schM=view&schPrjType=ALL&schProjectNo=20210121&schBookResultNo=14850 [Google Scholar]

7. Lee, D. H., Shin, J. Y. (2016). A study on counselors’ counseling experience participated in crisis intervention for Sewol ferry disaster: A phenomenological approach. Korea Journal of Counseling, 17(2), 373–398. https://doi.org/10.15703/kjc [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Campbell, R. (2002). Emotionally involved: The impact researching rape. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

9. Bride, B. E. (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 52(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/52.1.63 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Carmassi, C., Foghi, C., Dell’Oste, V., Cordone, A., Bertelloni, C. A., et al. (2020). PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lee, J. Y., Nam, S. K., Park, H. R., Kim, D. H., Lee, M. K. et al. (2008). The relationship between years of counseling experience and counselors’ burnout: A comparative study of Korean and American counselors. The Korean Journal of Counseling and Psychotherapy, 20(1), 23–42. [Google Scholar]

12. Maslach, C. (1982). Burnout, the cost of caring. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

13. Jenkins, S. R., Baird, S. (2002). Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma: A validation study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(5), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1573-6598 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. KSTSS (2020). The fourth national mental health survey: Korean society for traumatic stress studies. http://kstss.kr/?p=2065 [Google Scholar]

15. KSTSS (2021). The fourth national mental health survey: Korean society for traumatic stress studies. http://kstss.kr/?p=2065 [Google Scholar]

16. Guest, G., Namey, E., Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One, 15(5), e0232076. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Down-Wamboldt, B. (1992). Content analysis: Method, application, and issues. Health Care Women International, 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399339209516006 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. McInnes, S., Peters, K., Bonney, A., Halcomb, E. (2017). An exemplar of naturalistic inquiry in general practice research. Nurse Researcher, 24(3), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.2017.e1509 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lee, D., Kim, Y., Shin, J. (2015). A life history of the female counselor’s participated in Sewol ferry disaster counseling. The Korean Journal of Woman Psychology, 20(3), 369–400. https://doi.org/10.18205/kpa [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. James, R. K., Gilliland, B. E. (2001). Crisis intervention strategies. California: Brooks/Cole Thomson Learning. [Google Scholar]

21. Cunningham, M. (2003). Impact of trauma work on social work clinicians: Empirical findings. Social Work, 48(4), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/48.4.451 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Nam, H. K., Chang, S. S. (2016). The concept maps of novice and expert trauma counselors’ perceived impact of vicarious trauma and their coping strategies. Korea Journal of Counseling, 17(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.15703/kjc [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ursano, R. J., Fullerton, C. S., Norwood, A. E. (1995). Psychiatric dimensions of disaster: Patientcare, community consultation, and preventive medicine. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 3, 196–209. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229509017186 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Miller, L.(2002). Psychological interventions for terroristic trauma: Symptoms, syndromes, and treatment strategies. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 39(4), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.39.4.283 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Oh, M., Paik, J., Na, K., Kim, N. R., Chung, C. et al. (2015). Review of disaster mental health system in Japan. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, 54(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.4306/jknpa.2015.54.1.6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lee, D. H., Kang, H. S. (2015). The current status and implications of disaster psychological support system and crisis counseling program in the U.S. Korea Journal of Counseling, 16(3), 513–536. https://doi.org/10.15703/kjc [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cho, Y. (2017). A phenomenology study on vicarious trauma experience of counselor: Focusing on counselors who worked on disaster sites. Korea Journal of Counseling, 18(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.15703/kjc [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., Watson, P. J. (2002). 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part II. Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry, 65(3), 240–260. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kim, E. M. (2017). A qualitative study on growth of volunteer counsellor in disaster counseling. Korean Journal of Correctional Counseling, 2(2), 51–73. [Google Scholar]

30. Choi, H., Baek, H., Cha, J., Kim, E. (2015). A qualitative study on the experience of recovery from burnout among counselors in college counseling centers. The Korean Journal of Counseling and Psychotherapy, 27(4), 825–848. https://doi.org/10.23844/kjcp.2015.11.27.4.825 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Tedeschi, R. G., Calhoun, L. G. (2013). Posttraumatic growth in clinical practice. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

32. Gard, B. A., Ruzek, J. I. (2006). Community mental health response to crisis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(8), 1029–1041. https://doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1097-4679 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools