Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Methods Used to Reduce Bullying in Kindergarten from Teachers’ Perspectives

King Saud University, Riyadh, 999088, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Lina Bashatah. Email: ;

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(5), 639-653. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.025878

Received 03 August 2022; Accepted 21 November 2022; Issue published 28 April 2023

Abstract

This study identified the methods used by kindergarten teachers to reduce bullying among their students in and out of the classroom and examined differences based on the teachers’ years of experience and the number of courses on bullying they had taken. A descriptive survey using a questionnaire tool collected responses from 208 public kindergarten teachers in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The participants agreed with using such methods to reduce bullying among children as responding to parents’ reports and following up on the reasons for a child’s absence. They also agreed that bullying in the classroom could be reduced by methods such as avoiding comparisons between children and helping to build friendships among them. Moreover, the teachers agreed to use some methods in which the teacher relies on her authority, such as depriving the bully of play time and transferring him/her to another class. These methods were endorsed more strongly by teachers with at least 10 years of experience than by those with less experience, but no significant difference was observed according to the number of bullying courses taken. In addition, there is a lack of courses that focus on dealing with and confronting bullying in educational environments. The study highlights the need to provide teachers with training on how to deal with bullying and to set specific and clear policies on addressing bullying in kindergarten.Keywords

Kindergarten is an important preschool stage for young children because it contributes to building their personality as they begin to interact with their social environment. Interactions with peers take different forms, such as cooperation, competition, and building friendships, that help them increase their awareness of social values and envision their future social roles.

Interactions in kindergarten can be negative and hostile. This affects the balance and stability of the kindergarten and exerts negative psychological and social effects on the lives of the children [1]. Some children engage in negative behaviors with their peers, such as biting, hitting, teasing, ridiculing other children, excluding others from play, or trespassing on other children’s possessions. When these behaviors are repeated intentionally to cause harm, they are considered a kind of bullying [2,3]. Several studies have confirmed that bullying has become prevalent and can occur anywhere in kindergartens, such as in the classroom or the playground [4–6]. Bullying is aimed at harming another child, who becomes the victim of bullying. Snow [7] cited statistics from the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) showing that 20.4% of children aged two to five years who were bullied were subjected to physical bullying and 14.6% to verbal harassment.

Bullying has negative effects on bullied children, making them feel afraid, anxious, and uncomfortable. Because of their fear of bullies, they may prefer to withdraw from activities or refrain from attending kindergarten. They may also suffer more severe impacts, such as an inability to establish social relationships, low self-esteem, and an unwillingness to play with peers [8]. Bullies themselves may have difficulty benefiting from the educational programs provided to them and engage in serious criminal acts in the future if no serious action is taken to address their behavior [9].

Bullying has received global attention. Several laws have been enacted to prevent bullying and intentional and repeated persecution in schools and society. These include the Gun-Free Schools Act and other federal laws in the United States, the Child Safety Act adopted in the United Kingdom [10], and several local measures. The Personal Safety Project has been initiated to enhance personal safety among children, and a child support line has been established to take calls and provide immediate emergency assistance [11].

Moreover, many preventative programs have been designed to reduce bullying and its effects on children, such as the Dan Elwes Anti-Bullying Program and the Kiva Anti-Bullying Program. These programs aim to modify the school environment and train teachers to improve their ability to manage bullying behaviors and prevent bullying [12]. Global efforts to combat bullying emphasize the need to provide a psychologically safe environment from an early stage. This is consistent with the objectives of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s (KSA) Vision 2030 for educational development, which commits the nation to ensure quality education at the kindergarten stage. The KSA Ministry of Education’s [13] programs and campaigns for addressing bullying in public education are based on guidance service units that are responsible for implementing them and educating their employees. Since public kindergartens lack such guidance units or other resources designed to address children’s problems, the mechanism for addressing bullying in kindergarten may be unclear and dependent upon the teachers’ judgments. Thus, kindergarten teachers require preventive and curative interventions because their response to bullying among children can provide a sense of psychological security, and reassurance is among the most essential conditions that must be afforded to all children [14].

Therefore, further studies on bullying and how to address it are required in the KSA context, especially since the Arab world began paying attention to bullying in kindergarten at the local level relatively recently. Only Al-Hamid [8] and Al-Tuwaiher [15] have examined bullying at the local level in this context. Several Middle Eastern studies have revealed the effectiveness of specific teaching strategies or programs in reducing bullying among kindergarten children [4,16,17]. Several studies have also pointed to the importance of the teacher’s role in creating a safe classroom environment using these methods and strategies [15,18,19]. However, researchers have yet to identify which methods of reducing bullying at the kindergarten and grade school levels are suitable from the perspective of the teachers, who are responsible for providing a psychologically and socially safe environment for their students. This study addresses this research gap by seeking to answer the following questions:

What methods do teachers think are effective in reducing bullying among kindergarten children in general?

What methods do teachers think are effective in reducing bullying among kindergarten children specifically in the classroom?

Do participants’ responses regarding methods of reducing bullying differ based on their functional experience and the number of courses on bullying they have taken?

2 Addressing Bullying in Kindergarten

Different researchers have defined bullying in different ways, but most follow Olweus’s [20] definition: “when an individual is exposed continuously, and over long periods, to unacceptable practices by another individual or group of individuals” (p. 98). Bullying may consist of direct acts, such as hitting and verbal threats, or indirect ones, such as spreading rumors and excluding people from groups. It is often practiced in a hidden way, out of sight of adults [21].

Children in kindergarten participate as members of a group in an environment away from their families for the first time. This makes kindergarten a crucial stage in children’s social development, as it helps them understand relationships and develop the functional skills required for social interaction. Studies have revealed that kindergarten students may engage in negative behavioral patterns and bullying behaviors. These behaviors may continue until they enter the primary stage unless adults intervene and apply preventive and curative methods [22]. According to Tepetaş et al. [23], the most noticeable forms of bullying among children include forcing the victims to do things they do not want to do: bullies typically make the victims get wet, exclude them from joining the playgroup, call them bad names and ask other children to do so, and use their property without permission while threatening to break it if they ask back for it.

Alsaker [24] and Kochenderfer et al. [25] were among the first to examine the prevalence of bullying in kindergarten. Alsaker [24] interviewed 120 Norwegian children aged five to seven years and found that 17% and 10% of the children were perpetrators and victims of bullying, respectively. Similarly, Kochenderfer et al. [25] interviewed 200 American children of the same age and found that 20.5% of them were victims of bullying. Jansen et al. [26] found in the Netherlands that 17% of children aged five to six years were bullies, 13% were bullies/victims, and 4% were victims. Shin [6] found that 18.5% and 23.6% of Korean children aged four to six years were bullies and victims, respectively. Prevalence rates of 31.4%, 29.4%, 39%, and 4% have been found for verbal bullying, physical bullying, social exclusion, and spreading rumors, respectively, in Greek kindergartens [27].

Gender affects children’s practice and experience of bullying. Grünigen et al. [28] found that male kindergarten students were bullied more frequently and were more likely to practice bullying behaviors than their female counterparts. Females have been found to practice indirect forms of bullying, such as excluding and isolating victims from groups and spreading rumors, whereas males appear to practice direct forms of bullying, such as beating and uttering insults [29,30]. Vlachou et al. [31] found that female victims of bullying are more likely to be bullied in relationships than males, who were found to be more frequently subjected to physical bullying; however, both sexes were equally vulnerable to verbal bullying.

Sakran et al. [32] proposed that family values may contribute to the development of bullying among children. They argue that some families encourage their children to be dominant and controlling because they believe that intimidating others is a good way to solve problems. Additionally, the high popularity of bullies among peers and their status as favorite playmates may aggravate their bullying behavior [12,33]. Peer relationships in kindergarten are fundamental to social development. Children who lack friends are easy targets for bullying. According to Coloroso [34], another reason for bullying is the existence of differences among children, including biological (e.g., age, color, height, weight, physical ailments), cultural (e.g., race, regional location, religion, language), and less significant (e.g., wearing glasses, being new in class) differences. For example, Repo et al. [35] found that children with special needs between the ages of three and six years were highly vulnerable to bullying.

Vlachou et al. [31] showed that bullying in kindergarten occurred almost twice as often in the playground and other outdoor spaces as it did in the classroom because of the lack of supervision of children by authorities like teachers. Bullying also occurred more often in places beyond the teachers’ line of sight, such as in toilets, corridors, and the back of classrooms. Moreover, bullying in kindergarten can be enabled through the provision of “educational corners” in the classroom. For example, noisy, dramatic play and building/demolition corners provide a child greater freedom in their play and thus more opportunities to practice bullying; by contrast, bullying is less encouraged in quiet corners because the child is required to adhere to specific rules [36].

Bullying among children has gained considerable attention because of its negative effects on all parties (the bully, the victim of bullying, and the onlookers). Many educational institutions suffer from its consequences, which may appear soon after its occurrence or later in life [14,29]. For example, Almuneef et al. [37] found via the KSA’s National Family Safety Program that male participants who were bullied during the first 18 years of their lives had a higher prevalence of smoking, drinking alcohol, and drug use, while their female counterparts were more predisposed to suicidal thoughts and psychological problems.

2.2 Preventive and Remedial Methods for Bullying

Proactive preventive measures based on the principle that children in kindergarten must be protected and provided a psychologically safe environment are the first steps in confronting bullying behaviors. These measures must eliminate the factors that lead to the behaviors and help provide children with the social and emotional skills they need to address bullying behaviors prospectively [38].

Reducing bullying requires cooperation between kindergartens, parents, and teachers. Enhancing their awareness of its nature is the first step toward a safe kindergarten that does not accept bullying [39]. Al-Omari [40] indicated that kindergartens can prevent bullying among children in three ways. The first is by training kindergarten staff in the mechanisms of detecting bullying and methods of dealing with it. The second is by holding awareness-raising workshops on bullying to introduce children to its forms and to ways of dealing with bullies. The third is by conducting awareness-raising meetings for parents to educate them about bullying and its effects, signs, and indicative measures. Goryl et al. [41] found that kindergarten staff was weak in responding to bullying because of a lack of awareness of the issue, their view of bullying as a normal part of a child’s development, and their sense that it was an unacceptable behavior without a clear definition of its nature and characteristics. Therefore, bullying prevention policies are often non-existent or are integrated into another policy such as a behavior management policy that does not classify bullying behaviors as bullying.

Some kindergartens attempt to reduce bullying by providing teachers with guides on how to use kindergarten activities and curricula in a way that allows them to manage bullying children and teach them how to practice positive behaviors with their peers and present other activities that can enhance the social skills of their victims [29]. Kindergarten teachers are a model for children in their dealings with others because of their strong social and emotional relationships with the children and the time the children spend with them throughout the school day. Accordingly, teachers must show respect and acceptance of the differences in abilities and cultural, social, and economic backgrounds of the children in their class, without distinction or discrimination [42]. Moreover, dialoguing with the children about bullying, including giving examples and discussing strategies for dealing with it, helps prepare them to deal with any future bullying situations they may face. To prevent bullying, children’s awareness should be raised continuously throughout the school year by regularly supplying the library with comics and books dealing with bullying, accepting human differences, and social values, such as helping others [38]. Saracho [3] argued that kindergarten teachers should work to develop friendships between children, prevent the isolation of any children, and encourage withdrawn children to participate in group activities, as a lack of friends can put a child at risk of becoming a victim of bullying. Such children can benefit from having a friend by their side to protect them from bullies. Teachers must also set clear classroom standards and rules against bullying and inform the children of them; establish consequences for violating them; integrate the need to confront bullying into the content of classroom education and activities; and promote attitudes of acceptance, respect, and tolerance among the children [43].

The teacher directly dealing with bullying situations when observed shows the bully that the teacher does not tolerate these behaviors, which will reduce them. The first step in dealing with bullying is starting a dialogue between the bully and the victim individually and separately. This dialogue should make clear to the bully that his/her behavior is unacceptable. It should also provide support to the victim by listening carefully to everything he/she has to say and helping him/her express his/her feelings through appropriate activities, such as discussion, drawing, writing, and role-playing [44]. The teacher should help develop the social skills of bullying victims, including the skills of making friendships, self-control, helping others, and expressing and defending their rights. This can be achieved through social modeling, role-playing, discussion and dialogue, and social reinforcement [45].

Burger et al. [39] identified three methods used by teachers to address bullying. The first is directed toward the bullies and involves asking them for suggestions on how to solve the problem, helping them achieve a sense of self-respect and self-esteem, and occupying them with activities. The second is directed toward the victims and involves training them to act decisively while being bullied and to stand up to the bully. The last requires the assistance of adults, who are expected to refer the matter to the school administration, communicate with parents to intervene to solve the problem, and engage in discussions with teachers. Burger et al. [39] indicated that methods in which teachers rely on their authority, such as depriving the child of play time or verbally reprimanding him/her in front of the teacher’s colleagues, have a negative impact. The bully may respond to this by limiting his/her direct bullying and replacing it with indirect forms that are difficult for the teacher to detect, which may prove harmful and achieve behavioral change only in the short term. Many programs have been developed to address bullying. Some of them are discussed below.

This program aims to enhance teachers’ ability to detect and prevent bullying behaviors in kindergartens and primary schools in Switzerland. It gives teachers confidence in their knowledge of bullying and enhances their ability to take necessary action. The principles of the program include cooperation and mutual support between teachers to solve bullying in their classes and continuous communication between kindergartens and parents. It also includes prevention strategies, such as identifying positive and negative punishments, using rules in class management, encouraging children to report undesirable behavior, promoting empathy, and understanding gender differences [46].

Established by the United States (US) Children’s Committee in 2013, this program aims to develop the social skills of children between the ages of 4 and 14 years. It focuses on improving the children’s social competence and aims to reduce impulsive and aggressive behaviors through modeling, practice, and role-playing to help children develop their abilities in empathy, impulse control, anger management, risk assessment, and decision-making. It includes a family guide and curricula, the content of which varies depending on the age of the children [47].

2.2.3 Olweus Bullying Prevention Program

This program, widely used in the US and Northern Europe, includes preventive and other curative methods designed to reduce bullying among children aged 8 to 15 years. It is implemented by the program’s employees, students, and parents and aims to improve peer relations and provide a safe school environment. It offers specific measures and interventions for use at the school, grade, and individual levels, all of which are required for success, based on several basic principles, including the need for the support and participation of adults, providing basic systems and regulations to prevent unacceptable behavior, and the need for adults to act as positive role models for children [48].

2.2.4 Kiva Anti-Bullying Program

This is an anti-bullying program used in Finnish schools with funding from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. It targets students aged 10 to 12 years. The program is based on research indicating that bullying behavior arises from the bully’s pursuit of a privileged position within the peer group and that bullying can thus be reduced through changes in peer group behaviors that reinforce bullying behavior. Its main objectives are to increase awareness of the role played by the peer group in the persistence of bullying, enhance empathy with and supportive strategies for victims, and provide students with the skills required to deal with bullying situations [49].

Some of these programs, such as the Second Step Program, focus on enhancing the social and emotional competencies of children. Other programs, such as the Bern Program, focus on raising awareness of the problem among teachers and students and training them to address it. These programs are implemented within a comprehensive school-wide anti-bullying policy. Perren et al. [50] stated that the characteristics of kindergarten bullies and their victims are very similar to those of older bullies and victims; therefore, many basic elements of prevention and treatment programs directed at older children can be used with younger children. Humphrey [22] excluded intervention aspects that kindergarten children may find difficult to comprehend and program activities that may require writing or reading skills.

The Ministry of Education estimates that about 2,082 public kindergarten teachers work in Riyadh, KSA [51]. This study’s participants consisted of 208 female teachers from government kindergartens in Riyadh, selected by simple random sampling. They represented 10% of Riyadh’s kindergarten teacher population. This number was chosen because the homogeneity of society in a given characteristics requires a small number of individuals to represent it [52]. This holds for our sample, as the population of female teachers agrees in several characteristics: They all work in the government public sector in the classes of children aged between four and six years, and they follow the national curriculum in environments that are almost identical in their characteristics and in the applicable laws and regulations.

This study used a descriptive survey design. Data were collected using an online survey, and informed consent was obtained from all participants before the survey process. The data were analyzed by identifying statistically significant and anomalous results. SPSS was used for the statistical analyses. After verifying the validity and reliability of the questionnaire and obtaining the approval of the Scientific research Ethics Committee at King Saud University, the researchers distributed 213 questionnaires electronically to potential participants through a text message sent by the Education Department in Riyadh region; 208 responses were obtained.

The two-part questionnaire was designed to match the environment and education system relevant to the kindergarten stage. It was created after a careful review of the literature and several international and local bullying-reduction programs. The first part deals with the participants’ backgrounds (i.e., years of experience and number of courses taken on bullying). The second part covered the methods used to reduce bullying and was divided into two sections. The first comprised 15 statements concerning methods used at the kindergarten level. The second comprised 14 statements concerning methods used in the classroom. For each statement, a Likert scale ranging from 4 (“strongly agree”) to 1 (“strongly disagree”) was used.

The questionnaire’s content validity and internal consistency were checked. In terms of validity, its initial form was validated by 12 faculty members with specialization and experience in the fields of early childhood, psychology, and bullying. Its internal consistency was tested in an exploratory sample, outside of the study sample, consisting of 30 parameters. The Pearson correlation coefficient was compared between the degree of each statement, the total degree of the axis to which it belonged, and the total score of the questionnaire. The correlation coefficient value for the 15 items on the kindergarten level (0.804) and the 14 items on the grade level (0.781) was high and statistically significant at the 0.05 level, indicating a high degree of internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess the questionnaire’s reliability. Cronbach’s alpha for the 15 items on the kindergarten level, the 14 items on the grade level, and the overall questionnaire were 0.941, 0.875, and 0.935, respectively, indicating high reliability.

The validity and reliability of the tool were confirmed by applying it to a small sample that was not part of the basic sample. The approval of the university’s Scientific Research Ethics Committee was then obtained, and the questionnaire was distributed electronically to the participants via text messages from the Education Department in Riyadh as well as from the researchers.

A t-test was used to test the differences in participants’ responses based on their years of experience, and a one-way analysis of variance (F-test) was used to test the differences based on the number of courses taken on bullying. The results of the t-test showed that the responses of participants with more than 10 years of experience (kindergarten level: M = 3.12, SD = 0.58; school grade level: M = 3.50, SD = 0.33) were significantly different from the responses of those with fewer than 10 years of experience (kindergarten level: M = 2.88, SD = 0.61; classroom: M = 3.34, SD = 0.41; kindergarten level: t = 2.87, p < .01; classroom: t = 3.22, p < .01). These results were consistent with Berger et al. [39] finding that more experienced teachers were more likely to use strategies based on working with the bullying child and the victim than teachers with less experience. However, they were inconsistent with Gurrell et al. [53] finding that there was no relationship between teacher experience and the ability to manage bullying incidents.

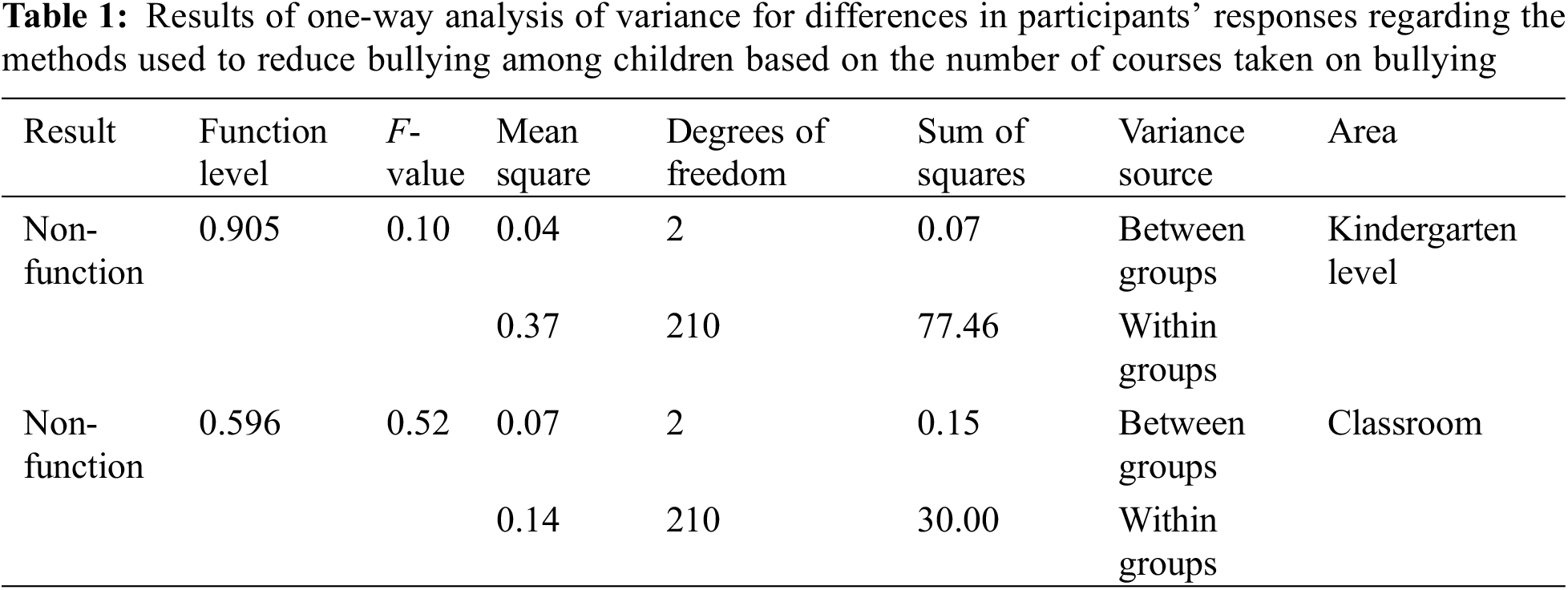

The responses showed no statistically significant differences based on the number of courses taken on bullying. Of the participants, 32% had taken courses and 68% had not (see Table 1). This may be attributable to a lack of training courses on bullying for teachers, especially kindergarten teachers, or keenness among the teachers to attend such courses. Moreover, the researchers observed that voluntary training courses aim to raise bullying awareness and discuss its causes and effects. They do not provide teachers with guidance on methods to reduce bullying in educational environments.

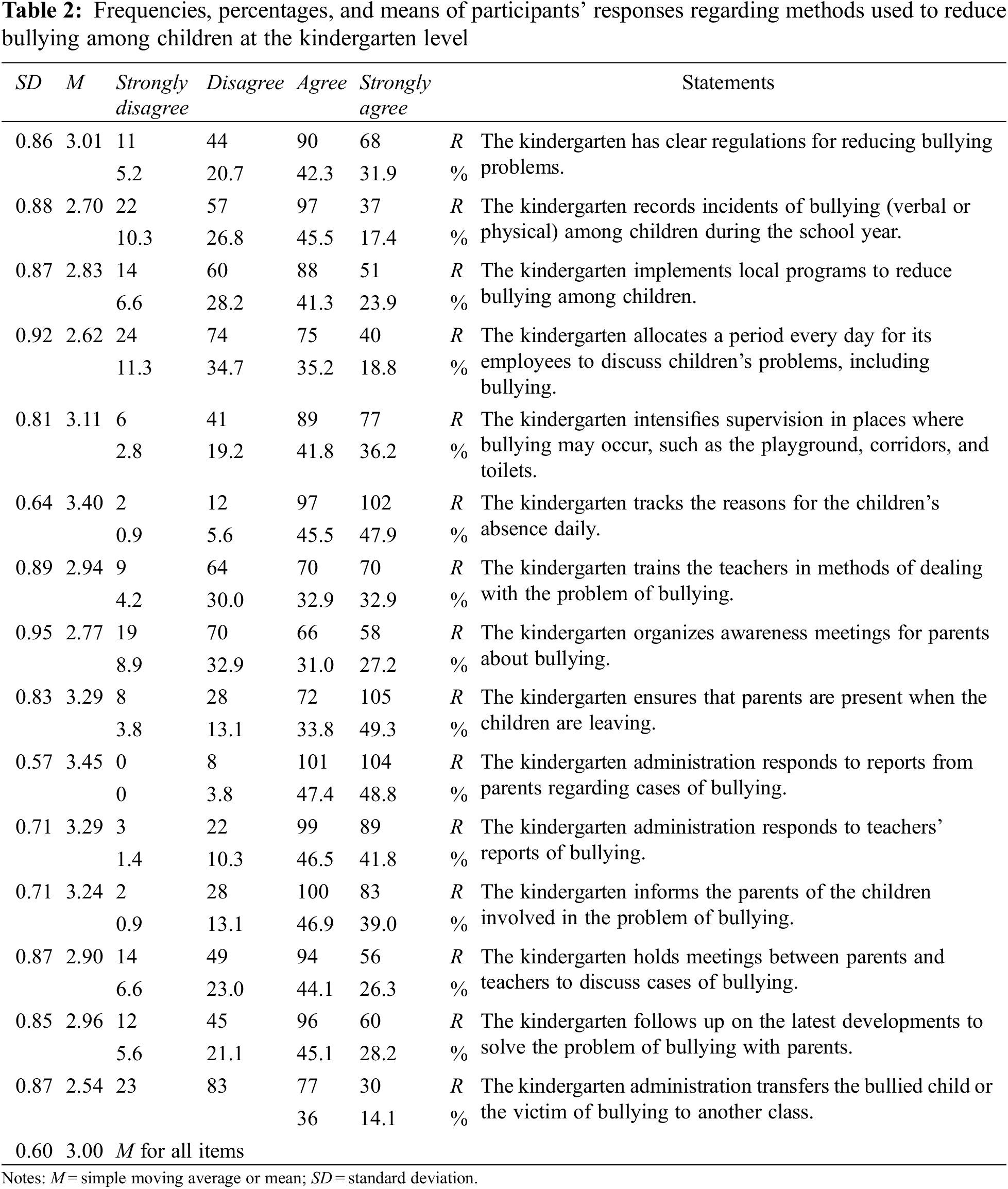

Table 2 presents the frequencies, percentages, means (M), and standard deviations (SD) of the participants’ responses to the questions on the methods used to reduce bullying among children at the kindergarten level.

The participants generally agreed with all the statements, with average responses corresponding to either “strongly agree” or “agree” (M for each item = 2.54–3.45, M for all items = 3; see Table 2). The statement “The kindergarten administration responds to parents’ reports regarding cases of bullying” obtained the highest mean score, 3.45 out of 4. This may be attributable to the kindergarten management’s awareness of the importance of working in partnership with parents to correct children’s behavioral problems and implement early intervention to reduce misbehavior so that it does not develop into more dangerous behaviors. This was consistent with the finding of Berger et al. [39] and Al-Zoubi [54] that cooperation and strengthening channels of communication with parents are important for reducing bullying.

The statement “The kindergarten tracks the reasons for the children’s absence” ranked second (M = 3.40), perhaps because the kindergarten management is aware that an unusually continuous absence may be an indicator of bullying. Recording absences is among the basic duties assigned to administrative assistants, as stated in the organizational guide for kindergartens [55].

The statements “The kindergarten allocates a period every day for its employees to discuss children’s problems, including bullying” (M = 2.62) and “The kindergarten administration transfers the bullied child or the victim of bullying to another class” (M = 2.54) ranked lowest. Regarding the former, this may indicate that the kindergarten management is aware that listening to teachers’ viewpoints on and experiences with bullying is important for identifying conditions that contribute to bullying and thus for controlling and reducing it. This result was consistent with Hussein [56], who argues that a kindergarten administration’s keenness to hold periodic meetings with teachers and listen to their views helps to eliminate and prevent bullying. Engaging adults, such as in discussing the problem with kindergarten teachers, is a useful strategy for developing bullying solutions [15,39]. Regarding the other statement (with the lowest score), separating the bully from the victim may help protect the victim from continuous harm and its effects. However, this may not sufficiently address the problem, as the perpetrator may resort to other forms of bullying. As indirect bullying is not punishable, this method may stigmatize both children without achieving the behavioral change needed to prevent the behavior. This interpretation is consistent with the claim of behavioral theory that bullying behavior will repeat if it is reinforced by individuals in the environment. Moreover, if the bullying child achieves his/her goal, he/she will repeat such behaviors to achieve a new goal and use it as a weapon to achieve his/her desires [57].

These results indicate that the participants’ viewpoints were consistent with the international programs and methods used to reduce bullying (such as the Bern, Always, and Kiva programs). These methods involve cooperation between teachers to solve the problem, and continuous communication between the school and parents to raise awareness about bullying. It also involves training teachers about bullying and how to confront it, holding periodic meetings to discuss problems, conducting periodic surveys to identify bullies and victims in classrooms, activating supervision and control over children, and applying the rules of behavior [46,58,59]. Some methods may be applied as legal norms that are not necessarily aimed at limiting bullying, such as following up on the absence of children and monitoring and supervising children in their gathering places. This was consistent with the finding in Goryl et al. [41] that 70% of the teacher participants cited policies for confronting bullying that included aspects of policies not specifically dedicated to bullying.

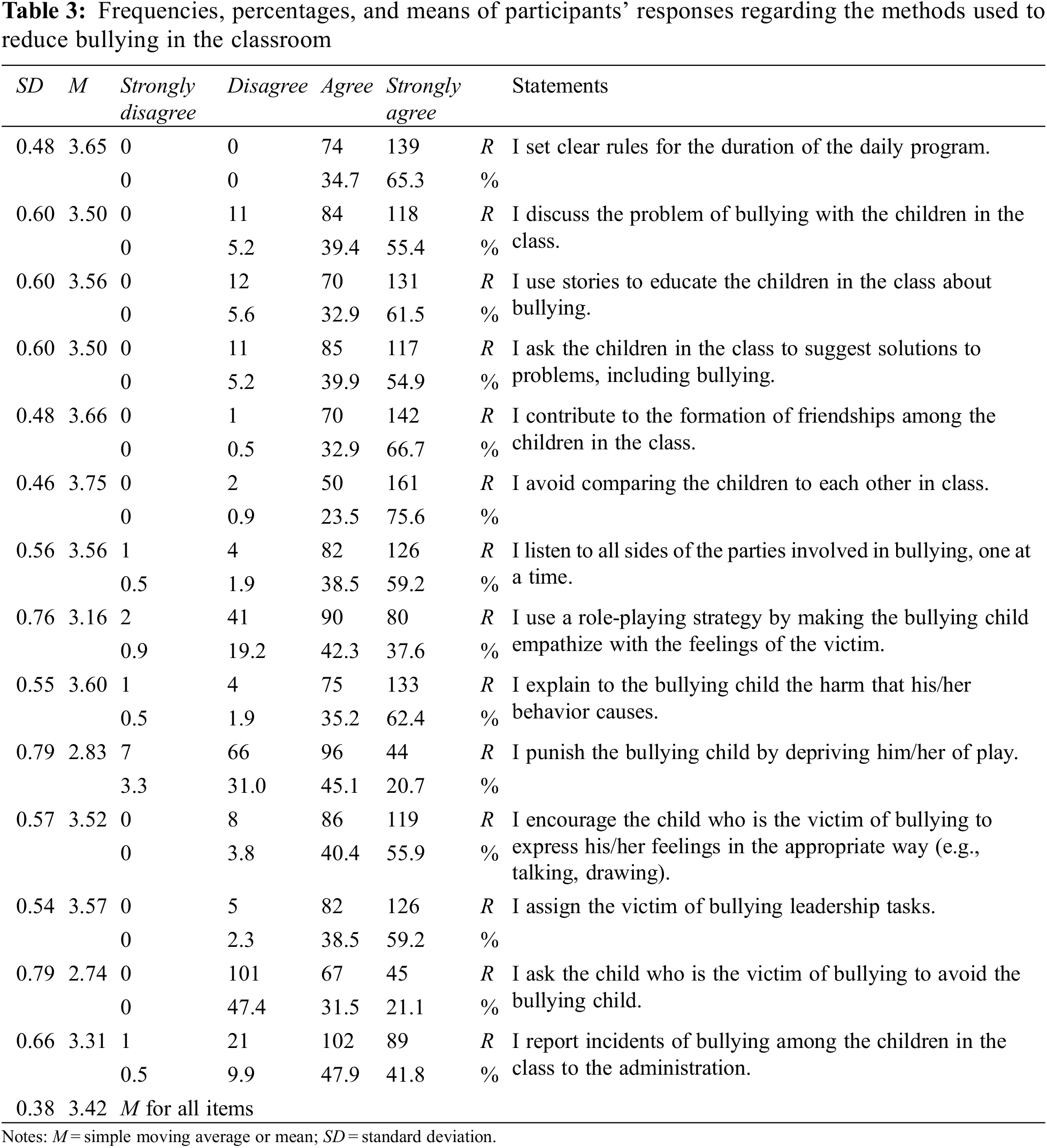

Table 3 presents the data on participants’ responses to the questions on the methods used to reduce bullying in the classroom.

The participants generally agreed with all the statements, with their average responses corresponding to either “strongly agree” or “agree” (M for each item = 2.74 –3.75, M for all items = 3.42; see Table 3). The statement “I avoid comparing the children to each other in the class” received the highest score (M = 3.75). This may be attributable to the teachers’ realization that comparing children creates a feeling of inferiority or a lack of self-confidence in them. In turn, this may cause some children to bully to increase their popularity or gain attention. This result was consistent with Dereli [42] finding that teachers’ acceptance of and respect for differences in children’s abilities and cultural and social backgrounds offer a positive model for children in their dealings with others.

The statement “I contribute to the formation of friendships among the children in the class” ranked second (M = 3.66). This may be attributable to teachers’ awareness of the importance of peer relationships in kindergarten as a key aspect of social development. Moreover, a lack of communication skills or difficulty making friends may put a child at risk of becoming a victim of bullying. Previous findings indicate that making friends is among the social skills that help reduce bullying among children [8,60].

The two statements “I punish the bullying child by depriving him/her of play time” (M = 2.83) and “I ask the child who is the victim of bullying to avoid the bullying child” (M = 2.74) ranked lowest. In the former case, this may be attributable to a lack of awareness among some teachers of the harmful effects of this method, which generates anger, frustration, and a lack of self-confidence. For this reason, the bullying child continues his/her behavior and frightens his/her peers to derive satisfaction from the suffering and misfortune of others. This result was consistent with Dereli [42], who found that 12% to 29% of teachers used this method to address aggressive behavior. Burger et al. [39] found that bullying children may respond to the teachers’ reliance on their authority by reducing direct bullying but increasing indirect bullying that is undetected by teachers. This is harmful as it achieves only short-term behavioral change. Regarding the statement with the lowest score, this result may be attributable to teachers’ poor knowledge about alternative methods of reducing bullying. This method may protect the victim only temporarily; the child may have difficulty when facing similar or more severe bullying in the future. This finding was consistent with those of Psalti [61], who found that teachers directed the victim to ignore the bully; of Dereli [42], who found that kindergarten teachers lacked knowledge of alternative functional methods and how to use them to reduce bullying; and of Lee et al. [62], who showed that mothers of bullying victims directed their bullied children to avoid the bullying.

Thus, the study participants’ general agreement with the questionnaire statements was consistent with the international programs and methods used to reduce bullying at the classroom level (such as the Bern, Second Step, Always, Kiva, and Respect Steps programs). These methods involve applying classroom rules; enhancing empathy skills; using strategy role-playing, problem-solving, dialogue, and discussion; encouraging children to make friends; encouraging victims to express their feelings; avoiding discriminating between children; talking seriously with the bullies and victims, and promoting supportive methods for victims [46,47,49,58].

This study’s findings revealed a high degree of agreement among participants about the necessity of interventions to reduce bullying. Such interventions are lacking in KSA kindergartens. Generally, the school’s administrative and educational staff respond to bullying by seeking to reduce it. They deal with parents’ complaints about bullying cases, and they inform the parents of children involved in such acts.

Additionally, the findings showed that teachers endorsed several negative methods to reduce bullying among children in the classroom, such as punishing the bullying child by not allowing him/her to play.

This highlights the importance of training programs for teachers to deal with bullying using effective educational methods and setting specific and clear policies on addressing the issue. These policies should provide a clear definition of bullying behavior, its forms, procedures for reporting it, and possible methods of limiting its effects.

The results of the current study may prompt researchers to conduct future qualitative studies on bullying in KSA kindergartens. Future studies should attempt to identify the prevalence of bullying, its causes, and its effects on children and determine kindergarten teachers’ awareness of these factors. Also, based on the results of the study the researchers, we see the necessity of adopting a policy to reduce bullying in early childhood educational environments, and the importance that this policy be based on the child rights approach, which emphasizes the right of the child to learn in a psychologically safe environment. Research has shown that the methods included within this policy are appropriate for the children’s age and are based on global experiences and scientific evidence, serving to create a safe environment that enhances positive social interactions between children. We recommend that future studies be conducted complementing this study with the aim of identifying the reality of bullying in early childhood, its prevalence, causes, and effects on the participating children, and applying experimental studies to proposed programs targeting children to enhance their awareness of the problem of bullying and ways to confront it.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gharib, N. (2017). The relationship between school bullying among middle school students and some personality characteristics and family relationships. Journal of Scientific Research in Education, 4(19), 257–286. [Google Scholar]

2. Helgeland, A., Lund, I. (2017). Children’s voices on bullying in kindergarten. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0784-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Saracho, O. N. (2017). Bullying: Young children’s roles, social status, and prevention programmes. Early Child Development and Care, 187(1), 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2016.1150275 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. El-Shinawy, M. (2018). Puppet theater as a method to reduce bullying in kindergarten. Childhood and Education Journal, 10(33), 385–444. [Google Scholar]

5. Sezgin, Y. (2018). Okulöncesi öğretmenlerin akran zorbalığı ilişkin algı ve görüşleri : Zorbalık davranışları tespitleri, zorbalık davranışları karşısında uyguladıkları stratejiler ve aldıkları önlemler. Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 33, 85–104. [Google Scholar]

6. Shin, Y. (2011). Social behaviors, psychosocial adjustments, and language ability of aggressive victims, passive victims, and bullies in preschool children. Journal of the Korean Home Economics Association, 49(6), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.6115/khea.2011.49.6.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Snow, K. (2014). Bullying in early childhood. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/blog/bullying-early-childhood [Google Scholar]

8. Al-Hamid, S. (2015). Differences in emotional intelligence among bullying categories of kindergarten children in Buraidah in light of some demographic variables [Unpublished Master’s Thesis]. Qassim University, Saudi Arabia. [Google Scholar]

9. Al-Ammar, A. (2017). Attitudes toward emerging patterns of cyberbullying and its relationship to internet addiction in light of some demographic variables among students of applied education in the state of Kuwait. Journal of Scientific Research in Education, 17, 223–250. [Google Scholar]

10.Al-Saud, J. (2020). Causes, effects, and methods of dealing with cyberbullying among primary school students from the point of view of primary school teachers. Saudi Journal of Educational Sciences, 68, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

11. Bunnouna, A. (2016). Kindergarten personal safety towards a safe environment for the child. Ministry of education. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Kindergarten Personal Safety Program. [Google Scholar]

12. Saracho, O. N. (2017). Bullying prevention strategies in early childhood education. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(4), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0793-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ministry of Education (2019). Education confronts bullying with awareness and discipline measures. https://moe.gov.sa [Google Scholar]

14. Hammam, N., Sweifi, G. (2018). A training program based on the borba theory of moral intelligence was used to reduce bullying behaviour in childhood and education. Journal of Studies in Childhood and Education, 5, 61–143. [Google Scholar]

15. Al-Tuwaiher, S. (2020). The role of the kindergarten teacher in reducing the bullying behavior of the kindergarten child. The Arab Journal for Scientific Publishing, 22, 205–234. [Google Scholar]

16. El-Sawy, I. (2019). A proposed program of kinetic activities to reduce bullying behavior among children from the perspective view of kindergarten teachers in Matrouh governorate. Childhood Education Journal, 11(37), 145–198. [Google Scholar]

17. Hashad, I., Ibrahim, H. (2018). Simplifying some modern concepts for the kindergarten child using the kinetic story and its impact on bullying behavior. Journal of Childhood and Education, 10(36), 227–286. [Google Scholar]

18. Al-Qahtani, N. (2015). The extent of awareness of bullying among primary school teachers and the reality of the procedures followed to prevent it in government schools in Riyadh from their point of view. Arab Studies in Education and Psychology, 58, 79–102. [Google Scholar]

19. Al-Shennawy, M. (2018). Puppet theatre as a method to reduce bullying in kindergarten childhood. Education Journal, 10(33), 385–444. [Google Scholar]

20. Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at school. In: Huesmann, L. R. (ed.Aggressive behavior, pp. 97–130. USA: Springer Book Archive. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9116-7_5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Omar, M. (2011). The next danger, riotous behavior in the school environment. Amman, Jordan: Zhahran Publishing and Distribution House. [Google Scholar]

22. Humphrey, L. (2013). Preschool bullying: Does it exist, what does it look like, and what can be done [Unpublished Master’s Thesis]. Catherine University, USA. [Google Scholar]

23. Tepetaş, Ş, Akgun, E., Altun, S. (2010). Identifying preschool teachers’ opinion about peer bullying. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 1675–1679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.964 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Alsaker, F. D. (1993). Isolement et maltraitance par les pairs dans les jardins d’enfants : Comment mesurer ces phénomènes et quelles sont leurs consequences. Enfance, 46(3), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.3406/enfan.1993.2060 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kochenderfer, B. J., Ladd, G. W. (1996). Peer victimization: Cause or consequence of school maladjustment? Child Development, 67(4), 1305–1317. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131701 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jansen, P. W., Verlinden, M., Dommisse-van Berkel, A., Mieloo, C. (2012). Prevalence of bullying and victimization among children in early elementary school: Do family and school neighborhood socioeconomic status matter? BMC Public Health, 12, 494. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-494 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Vlachou, M., Botsoglou, K., Andreou, E. (2013). Assessing bully/victim problems in preschool children: A multimethod approach. Journal of Criminology, 301658. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/301658 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Grünigen, R., Perren, S., Nägele, C., Alsaker, F. (2010). Immigrant children’s peer acceptance and victimization in kindergarten: The role of local language competence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28(3), 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151009X470582 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ibrahim, I. (2017). Building a scale of depicted bullying for a kindergarten child. Journal of Educational Psychology Research, 55, 648–677. [Google Scholar]

30. Smith, H., Polenik, K., Nakasita, S., Jones, A. (2012). Profiling social, emotional and behavioral difficulties of children involved in direct and indirect bullying behaviors. Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties, 17(3–4), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2012.704315 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Vlachou, M., Andreou, E., Botsoglou, K., Didaskalou, E. (2011). Bully/victim problems among preschool children: A review of current research evidence. Educational Psychology Review, 23(3), 329–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9153-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sakran, E., Alwan, E. (2016). The global construction of the phenomenon of school bullying as an integrative concept and its prevalence and justifications among students of general education in the city of Abha. Journal of Special Education at Zagazig University, 4(16), 1–60. [Google Scholar]

33. Alsaker, F. D., Stefan, V. (2012). The bernese program against victimization in kindergarten and elementary school. New Directions for Youth Development, 2012(133), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20004 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Coloroso, B. (2016). The bully, the bullied, and the bystander: From pre-school to high school: How parents and teachers can break the cycle of violence. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

35. Repo, L., Sajaniemi, N. (2015). Bystanders’ roles and children with special educational needs in bullying situations among preschool-aged children. Early Years, 35(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2014.953917 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Adams, J. (2008). Preschool aggression within the social context: A study of families, teachers, and the classroom environment [Unpublished Doctoral Thesis]. University of Florida, USA. [Google Scholar]

37. Almuneef, M., Hassan, S., ElChoueiry, N., Al-Eissa, M. (2019). Relationship between childhood bullying and addictive and anti-social behaviors among adults in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional national study. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 31(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2017-0052 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Freeman, G. (2014). The implementation of character education and children’s literature to teach bullying characteristics and prevention strategies to preschool children: An action research project. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(5), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-013-0614-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Burger, C., Strohmeier, D., Spröber, N., Bauman, S., Rigby, K. (2015). How teachers respond to school bullying: An examination of self-reported intervention strategy use, moderator effects, and concurrent use of multiple strategies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.07.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Al-Omari, S. (2019). The reality of the problem of school bullying among primary school students, prevention, and treatment. Arabian Journal of Science and Research Dissemination, 3(7), 30–44. [Google Scholar]

41. Goryl, O., Hewett, N., Sweller, N. (2013). Teacher education, teaching experience and bullying policies: Links with early childhood teachers’ perceptions and attitudes to bullying. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(2), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911303800205 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dereli, E. (2020). Physical and relational aggressive behavior in preschool: School teacher rating, teachers’ perception, and intervention strategies. Journal of Educational, 6(1), 228–252. https://doi.org/10.5296/jei.v6i1.16947 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Al-Miraj, S., Saad, X. (2020). Murad and Juma’a, Omaima. Bullying in the school: Risks, prevention, and intervention. Cairo: House of Science and Faith for Publishing and Distribution. [Google Scholar]

44. Hussain, T., Hussein, S. (2010). Strategies and programs for confronting violence and disturbance in education. Alexandria: Dar Al-Wafaa for Dunya Printing and Publishing. [Google Scholar]

45. Al-Khafaji, A. (2015). The effect of a counselling program on developing social skills for victims of school bullying [Unpublished Master’s Thesis]. Al-Mustansiriya University, Iraq. [Google Scholar]

46. Alsaker, F. D., Valkanover, S. (2012). The bernese program against victimization in kindergarten and elementary school. New Directions for Youth Development, 133, 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20004 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Committee for Children (2015). Second step. Bullying Prevention Unit: Second Step. [Google Scholar]

48. Olweus, D., Limber, S. (2010). The olweus bullying prevention program: Implementation and evaluation over two decades. In: Jimerson, S., Sweare, S., Espelage, D. (eds.Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective, pp. 377–401. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

49. Kiva Program (2020). KiVa is an anti-bullying programme. https://cutt.us/3Qr9z [Google Scholar]

50. Perren, S., Alsaker, F. (2006). Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01445.x [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. The General Administration of Education in Riyadh (2020). Statistical manual for the year 1441–1442. Planning and Information Department. [Google Scholar]

52. Abbas, M., Nofal, M., Al-Issa, M., Abu Awwad, F. (2015). Introduction to research methods in education and psychology. Amman, Jordan: Dar Al Masirah for Publishing and Distribution. [Google Scholar]

53. Gurrell, O., Hewett, N., Sweller, N. (2013). Teacher education, teaching experience and bullying policies: Links with early childhood teachers’ perceptions and attitudes to bullying. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(2), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911303800205 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Al-Zoubi, R. (2015). The degree of awareness of trainees about the causes of bullying in the first three grades and the procedures to address it. Al-Quds Open University Journal of Educational and Psychological Research and Studies, 3(12), 87–108. [Google Scholar]

55. Ministry of Education (2017). The Organizational Guide for Nursery and Kindergarten. 2nd edition. https://moe.gov.sa [Google Scholar]

56. Hussein, Y. (2019). The apparent bullying, the solution, and the state’s efforts to confront it. Cario: House of Flowers of Knowledge and Blessing. [Google Scholar]

57. Abu Al-Diyar, M. (2012). The psychology of bullying between theory and treatment. 2nd edition. Kuwait: Kuwait National Library. [Google Scholar]

58. Olweus, D. (2005). A useful evaluation design, and effects of the Olweus bullying prevention program. Psychology, Crime and Law, 11(4), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160500255471 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Salmivalli, C., Kaukiainen, A., Voeten, M. (2005). Anti-bullying intervention: Implementation and outcome. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(3), 465–487. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X26011 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Salem, A., Al-Nujihi, T., Abdel-Aal, N. (2020). Modifying the behavior of children who are victims of bullying in the light of a proposed cognitive-behavioral program. Journal of Scientific Research in Education, 21(14), 369–404. [Google Scholar]

61. Psalti, A. (2017). Greek in-service and preservice teachers’ views about bullying in early childhood settings. Journal of School Violence, 16(4), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2016.1159573 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Lee, S. H., Ju, H. J. (2019). Mothers’ difficulties and expectations for intervention of bullying among young children in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060924 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools