Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Do Child Characteristics Matter to Mitigate the Widowhood Effect on the Elderly’s Mental Health? Evidence from China

School of Economics, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, 230601, China

* Corresponding Author: Yuxin Wang. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(5), 673-686. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.026394

Received 02 September 2022; Accepted 12 December 2022; Issue published 28 April 2023

Abstract

This study empirically examines whether child characteristics mitigate the negative impact of widowhood on the elderly’s mental health using follow-up survey data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). A total of 5,326 older adults aged 60 years and older are selected from three waves of panel data (2013, 2015, and 2018). The findings suggest that respondents who experienced widowhood exhibit an increase in depressive symptoms. However, the higher income of children and frequent face-to-face emotional interactions improve the mental health of the widowed elderly. Moreover, heterogeneity analyses show that the buffering effect of higher child income is more significant among men and the Midwestern widowed elderly, and frequent face-to-face emotional interactions are more effective in improving the psychological status of women and the Midwestern widowed elderly. In the special social and cultural background of China, family members remain the main support for the elderly, and the current social pension system is still imperfect. Therefore, children should strengthen emotional communication with their parents while increasing their economic income. In that way, widowhood can achieve both material and spiritual prosperity. The government should identify the vulnerable groups among the elderly widows and introduce policies aimed at improving their mental health and reducing the disparity in mental health status.Keywords

Population aging is a global issue, especially in China, where the aging situation is becoming increasingly serious. There will be 267 million people over the age of 60 by the end of 2022, accounting for 18.9 percent of the total population. It is projected that the size and proportion of China’s population above the age of 65 will exceed those of all developed countries combined by 2040 [1]. As their physiological functions gradually decline with age, the elderly are at higher risk for psychological disorders such as dementia and depression, with a prevalence rate of dementia of 5.14% among the Chinese population over 65 years old [2]. The number of widowed elderly in China is gradually increasing as the country’s elderly population grows. According to the sixth national population census in 2010, there were 47.74 million widowed elderly in China, of whom 33.45 million were widowed women and 14.19 million were widowed men, accounting for 26.89% of the total older population. By 2025, the number of widowed people over 60 is predicted to reach 118 million, of whom 94.49 million are women and 23.91 million are men, 2.5 times larger than those in 2010 [3]. Therefore, the increasing number of elderly widows in China will greatly raise the strain on families and the social security system.

As one of the most devastating events in our lives, being widowed has a negative effect on older adults, with those who have lost their spouses experiencing deteriorating physical health, increased mortality risk, and exhibiting more psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety [4–7]. The loss of a spouse suggests that the elderly lose their long-term stable resources for emotional and functional support, leading to being more dependent on their children and other family members than before. In particular, children are the most important resource on which the widowed elderly can rely in China, due to the culture of filial piety. Therefore, children’s support plays an important role in ensuring the mental health of the widowed elderly. Considering the intergenerational ties of Chinese families, child support can be divided into two aspects: economic support and non-economic support. In light of that, it is essential to examine the impact of widowhood on the elderly’s mental health as well as the mechanism through which children’s support affects the widowed elderly, to promote active aging and achieve the strategic goal of a “Healthy China”. There are disparities in regional economic development in China. In addition, men and women have different degrees of psychological response to family relationships due to innate differences in perception. There is no doubt that these factors should be considered to ensure the proper implementation of social security policies.

This paper attempts to provide empirical evidence for promoting the widowed elderly’s mental health from the perspective of child support by using data from three rounds of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), conducted in 2013, 2015, and 2018. At present, few studies have explored the causal relationship between widowhood and health degradation among the Chinese elderly population. Specifically, this study contributes to the literature in the following ways. First, most of the existing studies focus on the correlation analysis between widowhood and mental health rather than the causal analysis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first rigorous empirical study using Chinese data to examine the causal relationship between widowhood and the mental health of the elderly. Second, as children are the most important resource for the widowed elderly to rely on in the Chinese traditional family-based pension model, this study examines the moderating effect of being widowed on the mental health of the elderly from the new perspective of child support. Furthermore, we investigate whether regular face-to-face communication and children’s average income level can mitigate the effect of being widowed on the mental health of the elderly. Third, this paper provides new insight into the mechanism through which children’s characteristics might affect the mental health of the widowed elderly. We also examine whether there are significant differences in mechanism between genders and regions, focusing on the differences between males and females when it comes to widowhood. Therefore, this paper estimates the impact of widowhood on the elderly’s mental health in a more comprehensive manner, which helps understand the health status of the widowed elderly and provides decision-making implications for effectively utilizing social and family support resources to improve their health level as a group.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the literature review. Section 3 introduces the data, variables, and empirical design. Section 4 reports empirical results, and Section 5 concludes the paper and provides some discussions.

2 Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1 Widowhood and Mental Health

The marital protection theory holds that marriage can promote health and survival by improving health behaviors and providing social and financial support for both spouses. As a supportive resource, a high-quality marital relationship can bring affection, stimulation, and behavioral confirmation to the elderly, which is beneficial for the individual’s mental health [8–10]. Therefore, a spouse plays a pivotal role in the later lives of older adults. Whereas the loss of a spouse is a painful life event that individuals are likely to experience in their later years, it often results in a loss of health for the widowed, precisely due to the loss of the sheltering role provided by the marriage itself. In terms of mental health, widowhood is associated with a range of subjective emotions, such as depression, loneliness, and reduced subjective well-being [11–13], so unexpected widowhood can lead to more long-term negative mental health outcomes [14]. Nakagomi et al. [15] found that widowhood is associated with an increased risk of depression in the older population. In a study of elderly people in Taiwan, Tseng et al. [11] found that spousal bereavement increases individual depression symptoms, but time could downplay the negative health impact of bereavement.

While it is generally accepted that widowhood is associated with an increased risk of depression, other studies find that widowhood does not necessarily lead to increased depression in older people. Using data from the American Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), McGarry et al. [16] found that the widowed often have to pay large amounts of out-of-pocket medical expenses for some time before the loss of their spouse, thus leading to a severe decline in their economic well-being, which they no longer need to experience after the death of their spouse. Based on the longitudinal data from the Elderly Welfare Survey in Anhui Province from 2009 to 2015, Liu et al. [17] found that widowhood significantly reduces the risk of death in rural older people. Wade et al. [18] suggested that the elderly with widowhood experience might have a more optimistic attitude to cope with the pressures of future life. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Compared to people who have been married, older people who have experienced widowhood suffer from more depressive symptoms.

2.2 The Moderating Effect of Face-to-Face Contact

In developed Western countries, it is more common to use the social pension model due to the existence of a sound social security system and abundant pension resources. The social security system in China, however, is still underdeveloped. Coupled with the extensive influence of Confucian philosophy and traditional concepts on society, the family is the strongest spiritual pillar for individuals. In addition, the current mainstream values of Chinese society emphasize the obligation of children to support their parents, which makes intergenerational ties within the family stronger than in the West. Kinship relationships formed by marital ties, such as those between spouse and children, play a role in protecting the physical and mental health of the elderly and their retirement life [12,19]. The elderly are more emotionally vulnerable after losing their spouse, and social interaction can help them reduce psychological stress reactions, relieve mental tension, and improve social adaptability [20]. Since emotional care is considered the most important filial act of children for older adults [21], emotional support provided by children can meet their missing spiritual needs, increase their sense of security and confidence in the future, and strengthen their sense of role control, which in turn positively impacts their physical and mental health [22]. Regular intergenerational interaction between children and parents through visits and greetings is beneficial to ensure the quality of life of the elderly [23], but adult children are often too busy with work to neglect their emotional needs. Intergenerational communication reflects a balance between traditional support culture and reality. The higher the frequency of communication, the more it reflects the children’s recognition of their obligation to support their parents. It also indicates that the closer the intergenerational psychological distance, the higher the probability of parents receiving spiritual support [23]. Therefore, frequent emotional interactions with children after the death of a spouse can provide older adults with some spiritual comfort, help them to resolve their pessimistic emotions and get rid of their low state, and effectively narrow the estrangement between generations, which may contribute to regulating older adults’ mourning of widowhood. Based on these, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Frequent face-to-face emotional interactions with children significantly reduce depression levels in widowed older adults.

2.3 The Moderating Effect of Children’s Income

People’s physical health depends not only on whether they receive sufficient spiritual support but also on the abundance of material resources available to them [24]. As one of the most intimate social relationships, marriage unites two people into an economic community, where spouses share family resources, share the cost of living, and face accidents and risks together. The death of one spouse means that the other spouse loses financial support from the deceased spouse, so she has to look for substitute economic support. According to Antonucci’s convoy model, the person progresses through three concentric circles, with each circle representing a different level of proximity to the focal person. Compared to the outer circle, the elderly tend to place their spouse and children in the inner core circle, have closer and more frequent contact with them, and receive more support from members of the inner circle [25]. As a result of the loss of a spouse, children become the main body of the inner core circle. According to the Grossman model expanded by Jacobson, each family member is a producer of health for herself and other family members, so her income and wealth can produce the health of all family members [26]. In China, dominated by the interactive family pension mode, financial support serves as a major aspect of aging. On the one hand, children with a steady income can assist their elderly parents in maintaining financial stability; on the other hand, some parents are relieved of the stress of having to work for their children. Higher-income levels of children can relax the financial constraints faced by the family and improve parents’ access to better medical resources by increasing the consumption and investment of family members, which in turn effectively relieves the psychological burden on the elderly parents and, to some extent, improves their mental health [27]. When children’s income levels are low, the scarcity of resources between children’s generations can increase the psychological burden of the widowed elderly. In addition, He [28] found that, from the perspective of network capital, the average economic income of older adult network members had a significant impact on their physical and mental status. Hence, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: The increase in the average income of children significantly reduces the level of depression among widowed older adults.

We use the panel data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) database in 2013, 2015, and 2018. The CHARLS1 is a nationwide field survey conducted by the National Development Research Institute of Peking University every two years since 2011, including about 10,000 households and 17,500 individuals in 150 counties and 450 villages. The questionnaire survey covers demographic information, family structure and transfer, income and consumption, health status, and other information that can meet our research needs.

Considering that the elderly over 60 are more likely to nominate their spouses and adult children than their parents as the inner circle of guardians in convey mode [25], this paper excludes samples from those under the age of 60. Then, following previous literature, this paper excludes individuals who were separated, divorced, widowed, or never married. Further, after classifying the two marital statuses of cohabitation and temporarily not living with a spouse due to work and other reasons into the group of being married, we divide the sample into two categories: individuals who had been married during 2013–2018; and individuals who experienced the shock of widowhood during the same period. The final sample includes a total of 5326 older adults, of whom 4796 had been married and 530 experienced widowhood shock during 2013–2018. Among them, 196 elderly people lost their spouses between 2013 and 2015, and 334 elderly people lost their spouses between 2015 and 2018.

3.2.1 Dependent Variable: Mental Health

We use a simplified version of the CES-D Scale2 [29] to measure whether the respondent is positive and optimistic, or anxious and depressed. This scale is widely applied in studies on mental health [30–35]. Lei et al. [32] verified the credibility and validity of the simplified CES-D Scale by using CHARLS data. First, there are ten questions in the CHARLS questionnaire to describe the symptoms of depression. Specifically, respondents were asked whether, in the last week, they had been bothered by small things; had trouble concentrating on things; depressed; found it hard to do anything; had hope for the future; scared; had trouble sleeping; were happy; lonely, and were unable to move on with their lives. Then, the simplified CES-D Scale requires the respondent to choose from the following four options: rarely or never (less than 1 day); some or a little of the time (1–2 days); occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3–4 days); and most or all of the time (5–7 days). The four options correspond to scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively, while the fifth through eighth symptoms have the inverse order, namely, 3, 2, 1, and 0. The CES-D Scale is the sum of these scores, which range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression and worse mental health status. Thus, a negative coefficient would suggest an improvement in mental health.

3.2.2 Independent Variable: Widowhood

This is a dummy variable: 1 for the widowed and 0 for the married.

Most scholars believe that factors like age, household, children’s quantity, and the logarithm of household consumption per capita would influence the elderly’s mental health [35,36]. We also include these factors as control variables to reduce potential biases.

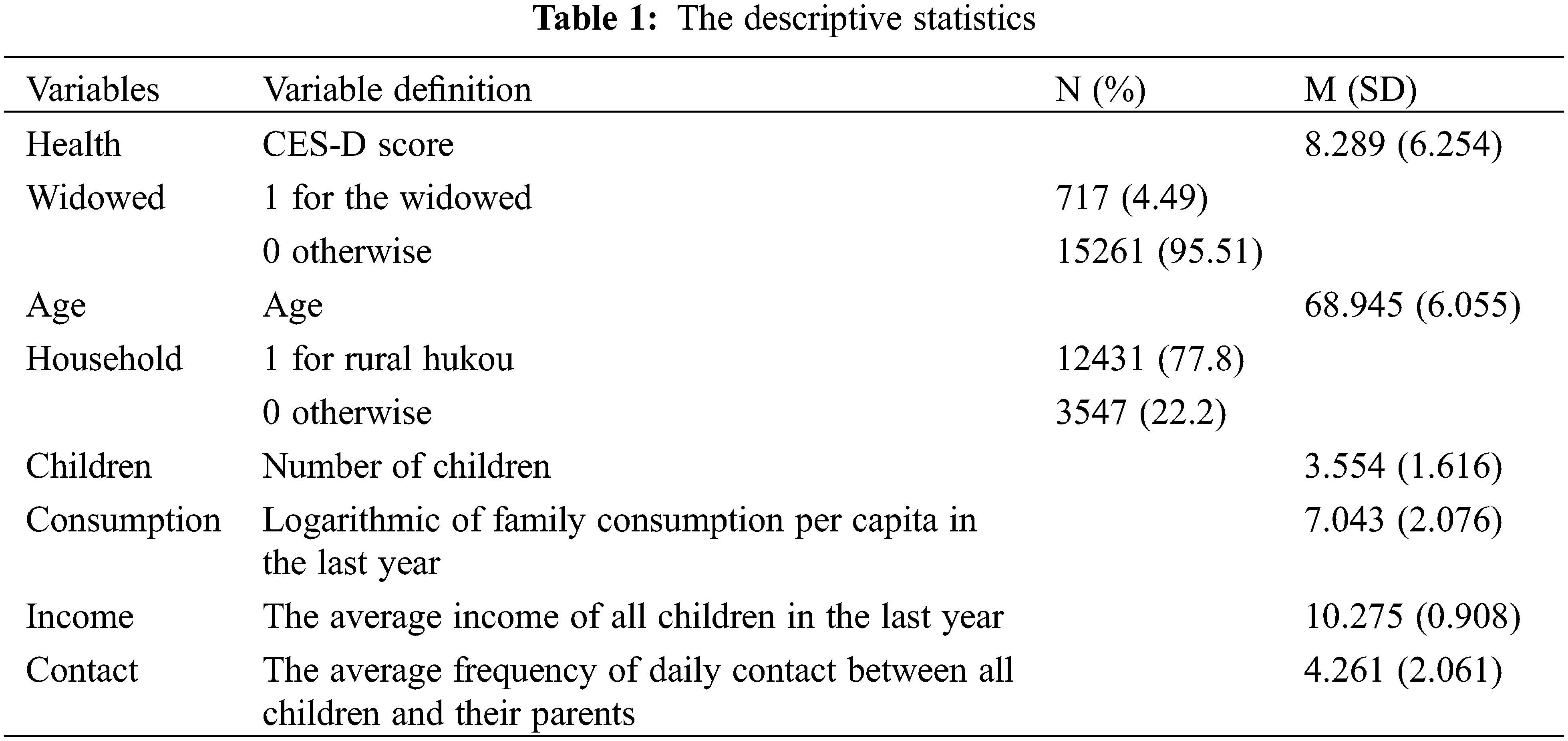

The children’s income and face-to-face contact are moderator variables to explore the mechanism through which child characteristics affect widowed older people. Specifically, children’s income is measured by the question “the child and her partner’s aggregate annual income for last year”. Since there may be more than one child in each household, this paper uses the average income of all children to analyze its moderating effect. Face-to-face contact is measured by the question “how often do you see your children” and the average frequency of daily contact between all children and their parents is used [37] (see Table 1)

To investigate the relationship between widowhood and mental health in elderly people, we use the difference-in-differences (DID) method and construct an empirical model as follows:

where Yit is the mental health status of the ith individual in year t. Widowedit is a dummy variable indicating whether the ith individual is widowed in year t, Controlit represents a group of control variables and T is a time trend variable. λi and λt represent individual fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively. In addition, Countiesi is a county dummy variable and εit is the stochastic error term.

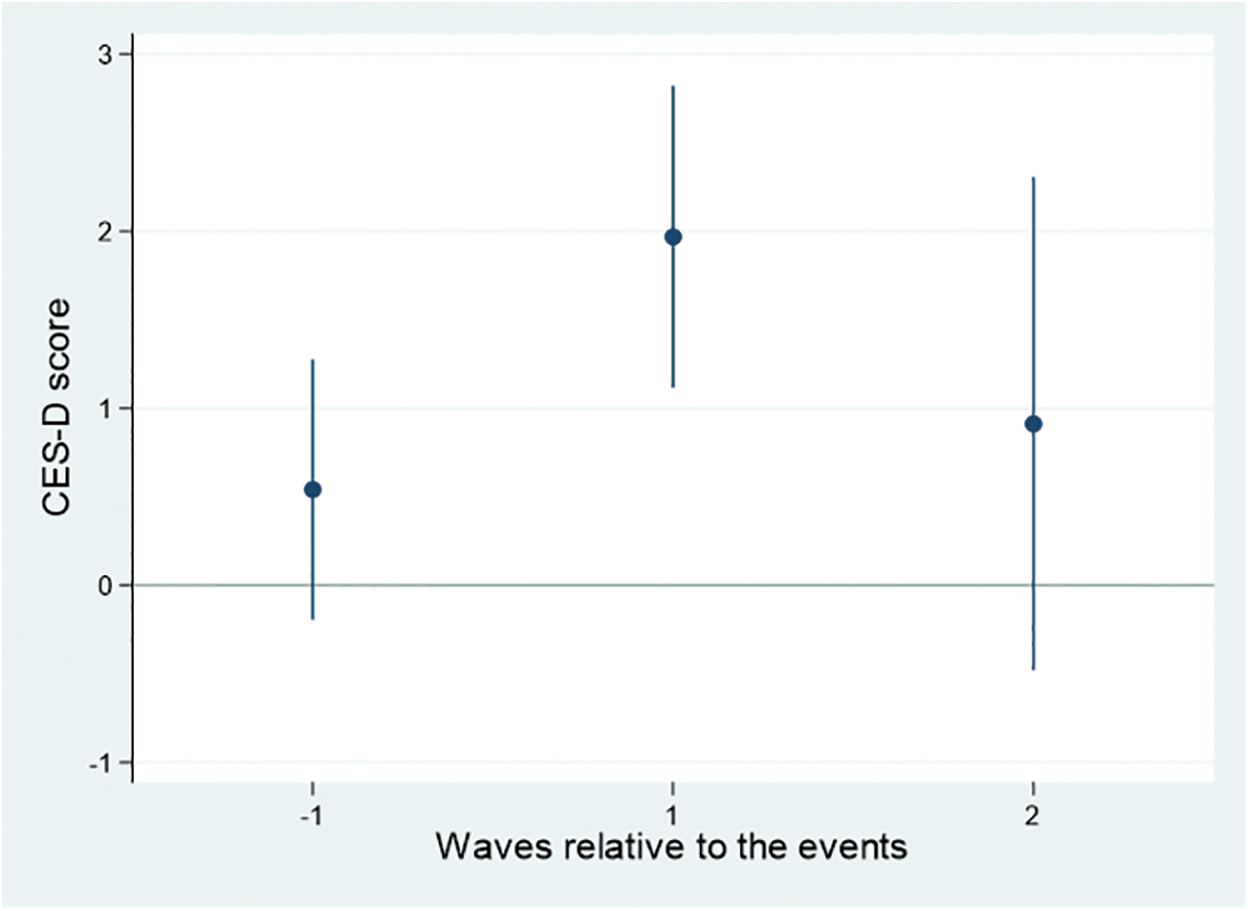

The premise of using the difference-in-differences (DID) method is to meet the parallel trend assumption, that is, that the health trend of the older people who have experienced the loss of a spouse is consistent with that of those who had not experienced it before the experiment. Otherwise, there is no comparability between the treatment and control groups. Therefore, a parallel trend test is necessary before using the DID method. We then used an event study model to investigate the parallel trends in the treatment and control groups3 [38]. The specifications of the event study model are as follows:

where k represents the k periods before or after the death of the spouse, ranging from the value of −2 to 2. To be specific, k = −2 indicates two periods before the loss of the spouse. Similarly, k = 2 indicates two periods after the loss of the spouse. For example, for the elderly who lost their spouses between 2013 and 2015, the year 2013 was the first period before widowhood (k = −1), the year 2015 was the first period after widowhood (k = 1), and the year 2018 was the second period after widowhood (k = 2). Postit is a dummy variable indicating whether the individual i has experienced the loss of a spouse in year t. It is equal to 1 only if the individual i experienced the loss of a spouse between waves k − 1 and k; otherwise, it is 0. In addition, we set the remaining variables as in the benchmark model. To avoid multicollinearity, this paper excludes the case where k is equal to −2 [39]. We assume that the coefficient of time trend dummy variables before the loss of the spouse is not significant, while the coefficient of time trend dummy variables after the loss of the spouse is significant. In that case, there is a parallel trend between the control group and the treatment group. The parallel trend test result is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The result of the parallel trend test

4 Empirical Results and Discussion

4.1 Impact of Widowhood on the Mental Health of Older People

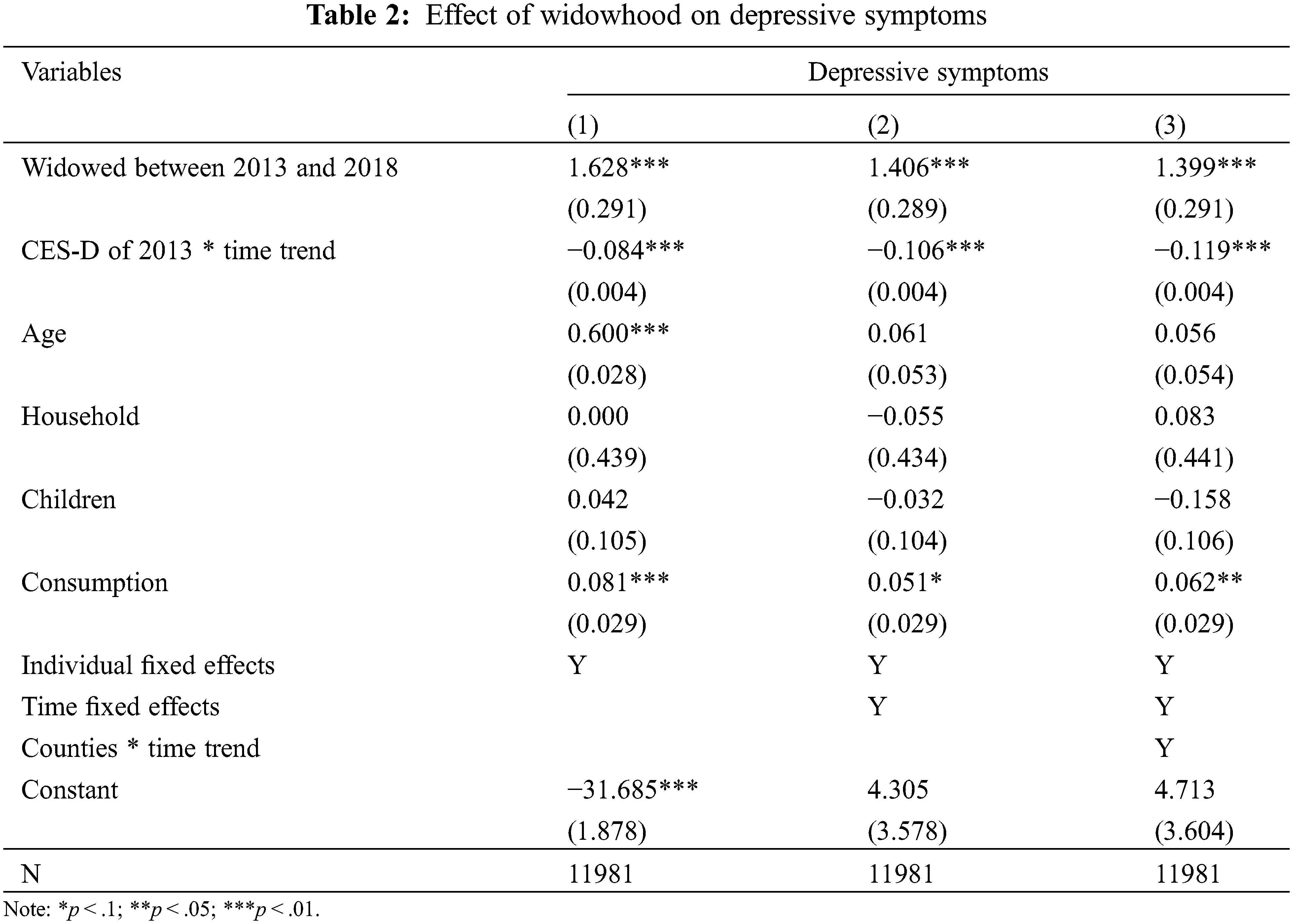

Table 2 reports estimated results of the aggregate effect of widowhood on the depressive symptoms of the elderly. Column 1 shows the regression results controlling for individual fixed effects only, column 2 shows the regression results adding time fixed effects to column 1, and column 3 introduces the interaction term between county dummy variables and time trends based on column 2. The results in column 3 show that the loss of a spouse has a negative impact on the mental health status of the elderly. The depression score of the elderly who experienced the shock of widowhood from 2013 to 2018 is 1.399 points higher than that of those who had been married, with significance at the 1% level. In addition, the increase in household per capita consumption also significantly increases the depressive symptoms of older adults. As mentioned above, the loss of a spouse deprives older adults of the supportive resources of their spouse, and the increase in consumption tightens the budgetary constraints faced by the household, thus increasing the psychological burden of the widowed elderly and triggering their mental depression. The number of children born to the elderly does not significantly affect the depressive symptoms of the elderly, indicating that “more children do not necessarily bring more happiness” in the current Chinese society. It can be seen that the increase in the number of children does not significantly improve the subjective well-being of the elderly [40].

4.2 The Moderating Effect of Child Characteristics

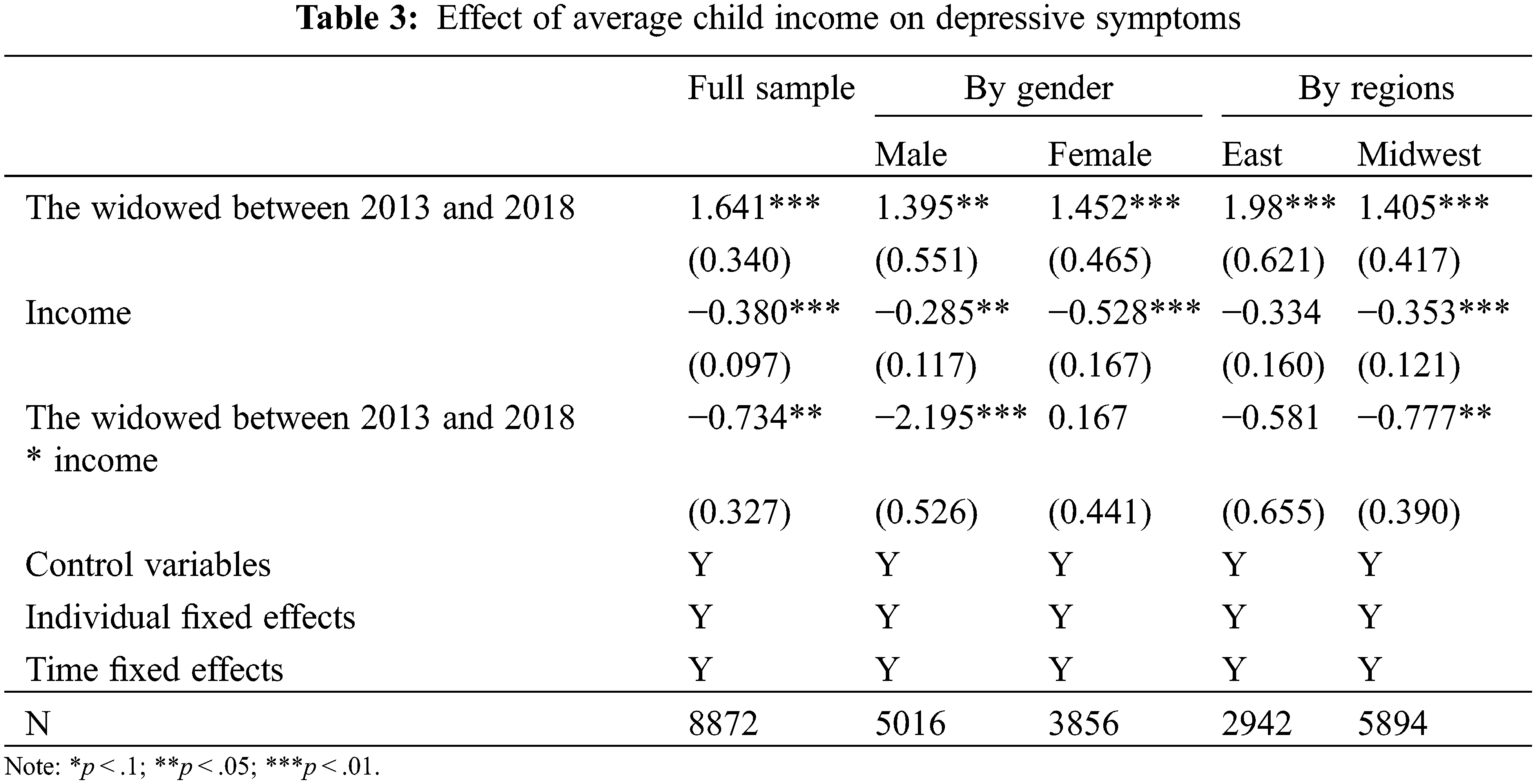

4.2.1 Moderating Effect of Average Child Income

The regression results shown in Table 3 consider the interaction between widowhood and children’s average income to examine the mechanism of average child income and test whether this moderating effect is significant. As seen from the interaction coefficient, children’s average income significantly reduces the negative impact of widowhood on the mental health of the elderly. The higher income level of children reduces the possibility of parents’ needing to give financial support and other assistance to their children. This fulfills the traditional wish of parents to see their children succeed while relieving the stress and anxiety caused by parents’ worries about their children. Thus, parents can better enhance their children’s sense of self-identity in their later years.

To further analyze the heterogeneity in this moderating effect, first, the subsamples are divided into groups of males and females according to gender to test whether there are gender differences in the moderating effect of average child income. The results show that children’s average income significantly reduces the scores of the elderly in the male group, but this finding does not hold in the female group. This may be due to the traditional division of labor in the family: that is, the male goes out to work while the female has to look after the house. In this way, women generally have less control over material resources. In the male group, the impact of intergenerational support from children is mainly material. Higher children’s income increases older males’ sense of control and allows them to maintain their role as “head of the household”. The higher the children’s income, the more adequate the potential retirement resources of the elderly. Children with higher incomes can provide direct financial rewards for their parents, and the material needs of older adults can be more easily met. Thus, older males can achieve better health by taking full advantage of the resources provided by their children.

Second, given the differences between regional economic development levels, two subsamples are divided into the Eastern and Midwest regions to test whether there are regional differences in the moderating effect of children’s average income. The results indicate that for the Midwest region, the average child’s income significantly mitigates the negative impact of widowhood on the elderly’s mental health. However, for the Eastern region, children’s income plays a minor buffering role. This may be due to the uneven economic development of regions. Generally, the income level tends to be higher in the Eastern region, so the widowed elderly have abundant material resources. They are more financially independent, suggesting that their better personal economic status provides strong protection and support for their physical and mental health [41]. As a result, the moderating effect of children’s income is greatly diminished by their lower economic dependence. In addition, the high level of social security in the Eastern region also dilutes the role played by children’s income. In contrast, in the Midwest region, due to relatively low levels of socio-economic development, the elderly generally lack independent economic ability. Thus, children’s higher income relaxes the budget constraint of the widowed elderly, which could better guarantee their quality of life in later life and improve their mental health.

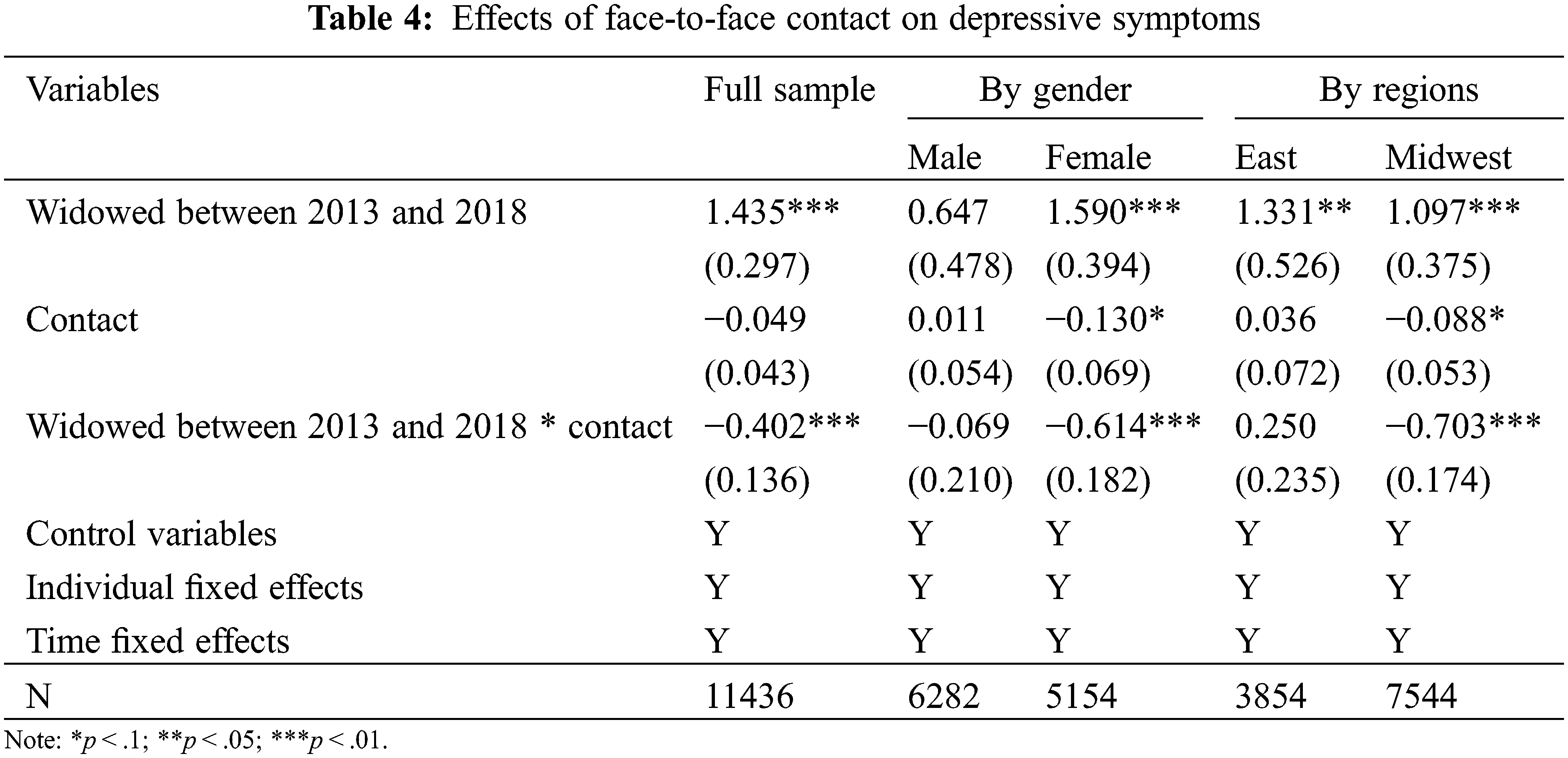

4.2.2 Moderating Effect of Face-to-Face Contact

The regression results shown in Table 4 consider the interaction between widowhood and face-to-face contact as a way to examine the moderating effect of face-to-face contact. The coefficient on the interaction shows that face-to-face contact significantly attenuates the negative impact of widowhood on the elderly’s mental health. After the loss of a spouse, older people are cut off from emotional communication with their spouse and are more eager for their children to connect with them emotionally. They can have a positive attitude toward life by interacting regularly with at least one child [42]. Frequent face-to-face contact can bring positive emotional experiences and help the elderly develop a better psychological state. The emotional care generated through face-to-face contact brings spiritual comfort to the elderly and strengthens intergenerational bonds, which in turn effectively reduces depressive symptoms in the elderly. Therefore, emotional support from children often acts as a buffer, and frequent face-to-face communication with children can be an effective measure to calm the negative emotions of the widowed elderly.

To further examine the heterogeneity of this moderating mechanism, first, two subsamples of males and females are divided according to gender to analyze whether there are gender differences in the moderating effect of face-to-face contact. The results show that frequent face-to-face contact with children significantly reduces the depressive symptoms of older people in the female group, but this finding does not hold in the male group. This may be because, in terms of emotional comfort, men and women differ in their degree of psychological response to family relationships due to innate differences in their perception. Women’s greater emotional needs make them more sensitive to intergenerational interactions than men, and more inclined to construct self-identity based on others’ responses in interactions with others. Older females, bound by traditional family roles, play a bonding role in the family and tend to have closer intergenerational ties with their children. In addition, they are less socially engaged because of their long-term involvement in family caregiving. After the death of a spouse, they are more dependent on children and more sensitive to children’s perception of intergenerational support; thus, frequent face-to-face contact with children can help them ease the grief of widowhood. Older males, however, have lower levels of emotional communication with their children [43]. They are generally less dependent on children and more resilient to negative life events than women. Thus, their strong social adaptation skills enable them to access a variety of ways to relieve their negative emotions, such as seeking social support outside the family.

Second, considering the regional differences in economic development levels, two subsamples are divided into the East and Midwest regions to test whether there are regional differences in the moderating effect of face-to-face contact. The results show that, for the Midwest region, face-to-face contact with children significantly buffers the negative impact of widowhood on the elderly’s mental health. For the East region, however, face-to-face emotional interaction does not exhibit a significant buffering effect. This could be attributed to the East region’s higher level of modernization and shifting intergenerational family attitudes. So the elderly in the East region are less dependent on their children for emotional support relative to those in the Midwest region. In addition, the East region has a high level of socio-economic development and abundant social security and welfare resources to meet the spiritual needs of the widowed elderly. In contrast, in the Midwest region, due to the constraints of economic development and financial expenditure, the pension service provided by the government remains at a lower level of material security and care services, and the ability to meet higher-level needs such as spiritual culture and mental health needs to be improved, which leads to the higher spiritual comfort needs of the widowed elderly for their children.

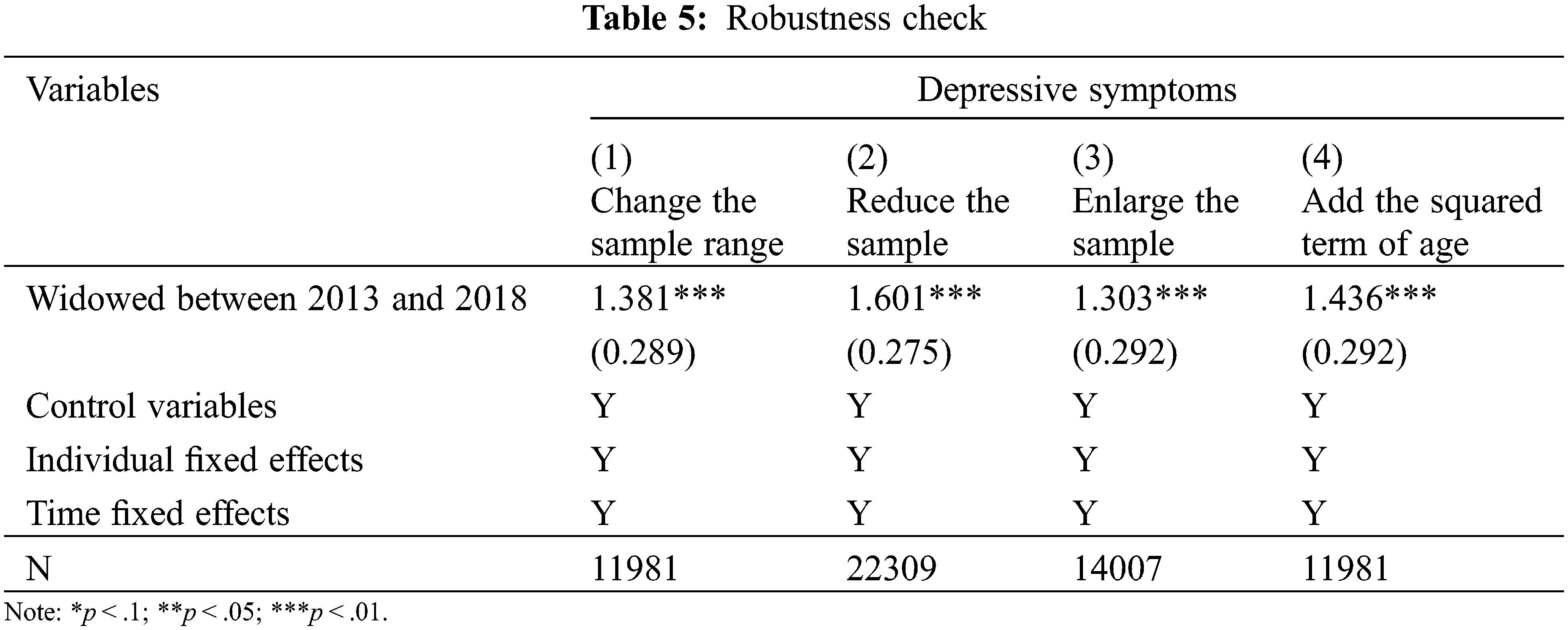

To ensure the reliability of our estimations, we conduct the following robustness tests. The results are presented in Table 5.

To eliminate bias due to measurement error or outliers, we exclude older people from the sample who have relatively fewer and relatively more depressive symptoms, i.e., the 1% at both ends of the depressive symptom distribution.

Considering that older people may be in better health due to genetic factors and other influences, this study further examines the effect of widowhood shock on health by limiting the sample to ages 50 to 75. The regression shows there is little change in the results, and the conclusions remain robust.

4.3.3 Increase the Sample Size

In the baseline analysis, the study removes the sample that had been in a state of widowhood, so this section retains this sample and retests the previous findings. The test results showed that older people who experienced spousal death are more likely to be depressed, indicating that the findings of this paper are robust.

4.3.4 Add the Squared Term of age

To avoid the deterioration of older people’s health as they age, and to account for the possible non-linear relationship between age and mental health in the elderly, this study refines the effect of age on depression in the elderly by incorporating the squared term of age into the model, and the results remain robust.

5 Conclusions and Implications

To actively address the various socio-economic challenges of population aging, the government should include the widowed elderly as a key vulnerable group for health management. Based on three rounds of panel data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) in 2013, 2015, and 2018, this paper empirically explores the impact of widowhood on the elderly’s mental health from the perspective of child characteristics. This study reveals the importance of accurately identifying filial support to protect the widowed elderly’s mental health and provides a useful exploration of the pathways of adjusting to negative emotions after widowhood, thus helping the government introduce relevant support measures in a targeted manner. We control for unobservable factors that do not vary over time by using a difference-in-difference model, which weakens the omitted variable bias of the model, thus bringing the results of the empirical analysis close to causality identification. The main findings of this paper are: first, widowhood significantly increases the level of depressive symptoms among older people as a whole; second, the higher income of children relaxes the family budget constraint and reduces the psychological burden of parents, which is beneficial to alleviating the psychological depression of the elderly; and third, face-to-face emotional communication with children can effectively alleviate the negative impact of widowhood on the mental health of the elderly, especially for women and the widowed elderly group in the Midwest region. These results also have implications for similar populations in other countries, especially in the Confucian cultural circle such as Korea, Japan, Singapore, etc. In response to the above findings, this paper makes the following recommendations:

In the special social and cultural background of China, family members remain the main support for the elderly, and the current social pension system is still imperfect. Children should strengthen emotional communication with their parents while increasing their economic income. In that way, widowhood can achieve both material and spiritual prosperity.

First, in terms of humanistic care, we advocate that children visit their parents frequently, talk to them regularly, and listen to their concerns, which could better utilize the tradition of spiritual support in contemporary society. In view of the sensitivity of elderly women to emotional care, it is suggested that the implementation of social security policies should reflect a gender perspective and be more inclined toward elderly women. Taking regional differences into account, it is also advised that more emotional care be provided to the elderly in the Midwest and that regular programs for psychological care for the elderly be implemented.

Second, in terms of economic resources, the government can increase support for families whose children are in poor economic conditions and introduce tilted policies to support them, such as providing various forms of employee compensation to low-income children. At the same time, based on the existing heterogeneity among different regions, the government should increase the allocation of economic resources in the Midwest region. This will gradually diminish the disparity in health quality between different regions and groups, enhance social equity, and eliminate policy bias.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China under Grant No. 17BJL044.

Author Contributions: All listed authors have substantially contributed to the manuscript and have approved the final submitted version.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1The database aims to collect high-quality microdata from Chinese residents over 45 for scientific research on the elderly.

2This is the Depression Scale used by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies.

3The event study method is routinely used by researchers to assess the credibility of the underlying parallel-trends assumption.

References

1. Du, P., Li, L. (2021). Long-term trends projection of China’s population aging in the new era. Journal of Remin University of China, 35(1), 96–109(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Jia, J., Wang, F., Wei, C., Zhou, A., Jia, X. et al. (2014). The prevalence of dementia in urban and rural areas of China. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 10(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.012 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wang, G., Ge, Y. (2013). Status of widowed elderly population in China and its development trend. Scientific Research on Aging, 1, 44–55(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

4. Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J. (2002). Health in household context: Living arrangements and health in late middle age. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 43(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090242 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Williams, B. R., Sawyer, P., Allman, R. M. (2012). Wearing the garment of widowhood: Variations in time since spousal loss among community-dwelling older people. Journal of Women & Aging, 24(2), 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2012.639660 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Jadhav, A., Weir, D. (2017). Widowhood and depression in a cross-national perspective: Evidence from the United States, Europe, Korea, and China. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73(8), 143–153. [Google Scholar]

7. Xu, J., Wu, Z., Schimmele, C. M., Li, S. (2019). Widowhood and depression: A longitudinal study of older persons in rural China. Aging & Mental Health, 24(4/6), 914–922. [Google Scholar]

8. Scafato, E., Galluzzo, L., Gandin, C., Ghirini, S., Baldereschi, M. et al. (2008). Marital and cohabitation status as predictors of mortality: A 10-year follow up of an Italian elderly cohort. Social Science & Medicine, 67(9), 1456–1464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.026 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Umberson, D. (1992). Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Social Science & Medicine, 34(8), 907–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(92)90259-S [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Schone, B. S., Weinick, R. M. (1998). Health-related behaviors and the benefits of marriage for elderly persons. The Gerontologist, 38(5), 618–627. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/38.5.618 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Tseng, F. M., Petrie, D., Leon-Gonzalez, R. (2017). The impact of spousal bereavement on subjective wellbeing: Evidence from the Taiwanese elderly population. Economics and Human Biology, 26, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2017.01.003 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Yang, F., Gu, D. (2021). Widowhood, widowhood duration, and loneliness among older people in China. Social Science & Medicine, 283(2), 114179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114179 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Cheng, X., Jiang, Q. (2017). Widowhood and the subjective well-being of elderly: Analysis of gender and location difference. Population and Development, 23(4), 59–69+79(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

14. Siflinger, B. (2016). The effect of widowhood on mental health-an analysis of anticipation patterns surrounding the death of a spouse. Health Economics, 26(12), 1505–1523. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3443 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Nakagomi, A., Koichiro, S., Hanazato, M., Kondo, K., Kawachi, I. (2020). Does community-level social capital mitigate the impact of widowhood & living alone on depressive symptoms? A prospective, multi-level study. Social Science & Medicine, 259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113140 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. McGarry, K., Schoeni, R. F. (2005). Widow(er) poverty and out-of-pocket medical expenditures near the end of life. The Journals of Gerontology, 60(3), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/60.3.S160 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu, H., Yang, R. (2019). A study on the correlation of the rural elderly’s widowhood to their mortality risk: The moderating effect of living arrangement and age group difference. South China Population, 34(4), 59–69(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

18. Wade, J. B., Hart, R. P., Wade, J. H., Bekenstein, J., Ham, C. et al. (2016). Does the death of a spouse increase subjective well-being: An assessment in a population of adults with neurological illness. Healthy Aging Research, 5(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

19. Li, A., Wu, R., Yin, X. (2020). The effect and mechanism of remarriage on the health of Chinese elderly. Population and Economics, 6, 78–95(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

20. Wei, Y., Liu, X., Zhang, Y. (2010). Impact of social support on loneliness of rural female elderly. Population Journal, 4, 41–47(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

21. Jia, C., He, W. (2021). Influence of intergenerational support on the health of the elderly: Re-examination based on the endogenous perspective. Populations and Economics, 3, 52–68(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

22. Tao, Y., Yu, S. (2014). The influence of social support on the physical and mental health of the rural elderly. Population & Economics, 3, 3–14(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

23. Zhou, R., Li, G., Wang, J. (2020). A study on the influence of intergenerational living distance on loneliness in elderly people living alone: An empirical analysis of 2661 elderly people living alone in urban. Northwest Population, 41(6), 2–14(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

24. Zhao, Y. (2008). Social network and people’s wellbeing in urban and rural areas. Society, 28(5), 1–19(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

25. Antonucci, T. C., Akiyama, H. (1987). Social networks in adult life and a preliminary examination of the convoy mode. Journal of Gerontology, 42(5), 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/42.5.519 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Jacobson, L. (2000). The family as producer of health−An extended grossman model. Journal of Health Economics, 19(5), 611–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6296(99)00041-7 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lv, G., Liu, W. (2020). Research on the heterogeneous effects of children’s education on the health of elderly parents in China. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 4, 72–83+127–128(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

28. He, Z. (2002). Socioeconomic status and social support network of the rural elderly and their physical and mental health. Social Sciences in China, 3, 135–148+207(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

29. Radloff, L. S. (1977). The ces-d scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhou, Q., Qin, X., Liu, G. (2018). To worry more about unequal distribution of wealth than poverty-impact of relative living standard on mental health among Chinese population. Economic Theory and Business Management, 9, 48–63(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

31. Zimmerman, F. J., Katon, W. (2010). Socioeconomic status, depression disparities, and financial strain: What lies behind the income-depression relationship? Health Economics, 14(12), 1197–1215. https://doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1050 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lei, X., Sun, X., Strauss, J., Zhang, P., Zhao, Y. (2014). Depressive symptoms and SES among the mid-aged and elderly in China: Evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study national baseline. Social Science & Medicine, 120, 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.028 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Qin, X., Wang, S., Hsieh, C. R. (2018). The prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among adults in China: Estimation based on a national household survey. China Economic Review, 51(2), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2016.04.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang, Y., Wang, L., Wu, H., Zhu, Y., Shi, X. (2019). Targeted poverty reduction under new structure: A perspective from mental health of older people in rural China. China Agricultural Economic Review, 11(3), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-12-2018-0243 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li, Q., Zhao, R., Zhang, T. (2021). Does the old-age insurance system mitigate the adverse impact of widowhood on health of the elderly? The Journal of World Economy, 9, 180–206(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

36. Tan, C., Luo, X., Li, Q. (2021). Analysis of the influence of widowhood on depression of Chinese elderly: Evidence from CHARLS. South China Population, 36(3), 56–66(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

37. He, Q., Tan, Y., Xie, P. (2020). Happiness or burden: The impact of grandchild care on the well-being of middle-aged and elderly people. China Economis Studies, 3, 121–136(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

38. Beck, T., Levine, R., Levkov, A. (2010). Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. The Journal of Finanace, 65(5), 1637–1667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01589.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhou, M., Lu, L., Du, Y., Yao, X. (2018). Special economic zones and region manufacturing upgrading. China Industrial Economics, 3, 62–79(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

40. Shi, Z. (2016). Does the number of children matter to the happiness of their parents? The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 5, 189–215+246 (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-016-0031-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wu, H., Jia, Y. (2017). Self-related health of the widowed elderly in rural and urban areas: Findings from the perspective of social support. Population and Development, 23(1), 66–73(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

42. Li, Q., Dong, J., Zhang, X. (2021). The effects of children’s quantity and quality on parental subjective well-being. Journal of China Normal University, 4, 150–165+184(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

43. Zhao, X., Li, J. (2019). The effect of widowhood on loneliness among Chinese older people: An empirical study from the perspective of family support. Population Journal, 41(6), 30–43(in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools