Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Qualitative Exploration and Correction Strategies of the Criminal Psychological Mechanism of the Burglars

1 Postdoctoral Station, China University of Political Science and Law, Beijing, 100088, China

2 College of Humanities and Management, Guilin Medical College, Guilin, 541000, China

3 School of Social Sciences, China University of Political Science and Law, Beijing, 100088, China

* Corresponding Author: Bo Yang. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(4), 595-611. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.027321

Received 24 October 2022; Accepted 12 December 2022; Issue published 01 March 2023

Abstract

In order to explore the criminal psychological mechanism of burglars, this study adopts the qualitative research method of grounded theory to conduct in-depth interviews with 41 burglars in two prisons in Jiangxi Province, China. Nvivo 11.0 was used to code-construct and qualitatively analyze the interview content in order to refine the influencing factors and psychological evolution process of burglary behavior. The findings revealed that (1) burglary risk factors include burglary cognition, burglary motivation, burglary decision-making, delinquent peers, burglary opportunity, and incomplete reformation. (2) There are three stages in the psychological evolution process of burglars: cognitive formation, motivational dominance, and behavioral decision. (3) The interpretation of the criminal psychological mechanism of burglars is a comprehensive and dynamic outcome of the interaction of internal and external factors that shape the individual. Participants’ inspection and non-participants’ inspection were adapted to verify the research results’ validity, which showed that the results were reliable.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

With the advancement of socialization, China’s economy has been growing steadily and rapidly, but crime remains a major problem in social governance. According to the most recent data from the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s public security departments accepted and investigated as many as 2.285 million and 1.872 million theft crimes in 2019 [1]. In China, property theft cases accounted for 30.3% of the total number of criminal cases from 2018 to 2019, with theft cases comprising more than half (62.2% of the total number of property theft cases). The incidence rate of burglary cases is the highest among theft cases (67.4%) [2]. A theft crime is also one of the crimes with the highest incidence rate in global property crime. As reported by the FBI, burglary accounted for 62.1% of all property crimes in 2018, with 376 burglary cases per 100,000 people [3]. Crime survey reports indicate that burglary is one of the most terrifying types of crime [4]. In spite of the fact that burglaries do not cause as much damage as violent crimes such as murder, rape, and robbery, burglary cases occur frequently with low clear-up rates, high recidivism rates, diverse locations, and easy commitment [5], which not only cause negative effects such as loss of citizens’ property, the decline in quality of life and anxiety at the personal level but also seriously endangering social order and public security [6]. Therefore, studies on burglary crimes and other problems have attracted a great deal of attention from scholars around the world.

Burglary is the act of repeatedly or repeatedly stealing a large quantity of public or private property for illegal possession [7]. The perpetrator of a burglary enters the residence of another person with the intention to commit theft [8]. The British “Theft Act” stipulates that it is theft to maliciously occupy the property of another and knowingly deprive him of his rights permanently. In Japanese criminal law, theft is the most common form of crime [9]. Burglary, on the other hand, refers to the act of illegally breaking into other people’s houses to steal their valuables [10]. It is stated in Article 242 of the German Criminal Code that burglary must take place “for the purpose of illegal possession by oneself or a third party”, that is, committing theft from another person’s house [11]. Currently, China’s academic circles focus primarily on the criminal subject, criminal behavior, sentencing, and other legal research and judgment on the crime of burglary in order to assist with the trial and detection of theft cases [12–14]. From the perspective of criminal law, burglary is a social phenomenon, and its genesis is a combination of socially established facts and legal considerations. The occurrence of burglary is the result of the interaction of situational factors and multiple causal factors, from a criminological standpoint. From a psychological perspective, burglary is the result of individual criminal psychological activity and is influenced by the offender’s psychological factors; thus, burglary is the result of the combined influence of the offender’s psychology and behavior [15]. Professor Fang Bo believes that criminal psychology emerges from a multilevel system. On the basis of his theory, Professor Luo Dahua proposed the synthetic agent theory of crime. This theory also considers the dynamic, structural, hierarchical, and holistic nature of individual crime causes. The internal and external factors of the offender, which interact and constrain one another, are responsible for the development of criminal psychology [16].

In Western countries, there have been a number of relatively systematic theoretical perspectives on burglary crimes, including rational choice theory, situational crime prevention theory, crime form theory, and the “center eight” criminal behavior risk factor framework, for instance [17–20]. In “Center Eight”, the framework of risk factors for criminal behavior proposes that personality, cognition, social connections, and history of behavior are the four most important factors for individuals to engage in criminal behavior, referred to as the “big four” risk factors [21]. A personality trait is a unique pattern that constitutes a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. This unique pattern contains the stable and unified psychological qualities that distinguish a person from others and often determine the consistent behavioral tendency of an individual. Cognition is the thought schema formed in the brain by the experience acquired through the cognitive process, and it is a kind of knowledge and experience network, which usually plays a role in facilitating individual behavior. Social connection mainly refers to the interaction among individuals, the external environment, and the interpersonal network that has an impact on individual behavior. Behavior history reflects the individual’s bad behavior history or criminal history. For burglars, a high recidivism rate is a common situation among burglars. Thus, the behavioral history of burglars and the evolution of their psychological processes of repeated theft are areas worthy of further research in the future.

In the aspect of empirical research, questionnaires or behavioral experiments are used nowadays in China to investigate the psychological and behavioral characteristics of burglars [22,23]. Based on the current research on the influencing factors of criminal behavior, it is found that individual personality, family-rearing style, social support, self-control level, coping style, and decision-making behavior are all important factors in the system of factors that constitute criminal [24–27]. However, due to the late kick-off of empirical research on burglars in China, the current research on the psychological and behavioral traits of burglars lacks systematization and depth. In terms of criminal correction, there is little attention and investment in burglars. In contrast, the theoretical research systems on burglary crimes in western countries are comparatively advanced. There are more empirical research findings [28–30]. Among them, the study of burglars’ spatial-geographic travel behavior (Journey-to-Crime) is an area that has received a lot of attention from western scholars. It focuses on the burglars’ selection of distance, location, geographic location, and travel tools during the commission of the crime. The objective of the research is to comprehend burglars’ behavioral patterns in order to provide an effective theoretical foundation for the prevention, control, and investigation of burglary cases. Why do burglars have such a high recidivism rate? How can burglary offenses be effectively prevented? In many aspects, it is still necessary for empirical research to determine whether the theoretical and practical experience of Western burglars is applicable to China’s local circumstances. In today’s society, it is difficult to prevent burglaries, and the problem of organized, gang-based, and diverse burglary crimes is prevalent. To effectively prevent the occurrence of burglary, in the first place, it is to comprehend the causes and processes of behavior formation; therefore, it is imperative to study the psychological and behavioral mechanisms of burglary.

Coleman has said, “The key to effective deterrence and control of criminal behavior is to understand the perpetrator’s process” [31]. Burglary, as a typical deviant behavior, cannot be induced by controlling the psychological variables to get the psychological variables associated with burglary in a way that induces individuals to commit crimes. Previous studies on deviant behaviors usually adopt a retrospective research approach, in which people with deviant behaviors are used as the research objects to invert the risk factors that are closely related to deviant behaviors. Based on this, this paper adopts the qualitative research method of Grounded theory to comprehensively explore the psychological mechanisms of burglars.

In recent years, qualitative research has been widely used in the fields of criminal psychology, psychological counseling and health care abroad, and starts to gain momentum in China. There are three reasons for adopting the qualitative research method in this study. First, the qualitative research method is exploratory and can well reveal the psychological process of burglars. Second, the researcher is participatory in qualitative research, which is conducive to obtaining deep information related to burglary behavior. Third, Grounded Theory, as a means of qualitative research, has unique advantages in theory construction [32]. This paper takes burglars as the research object, explores the risk factors closely related to burglary behavior through in-depth interviews, combines the research method of Grounded Theory, clarifies the inner mechanism of burglary behavior, and tries to construct an explanatory model of the psychological mechanism of burglary crime in order to provide a theoretical basis and correction basis for preventing and controlling burglary crime.

According to the principle of “purposive sampling,” the 41 most representative and information-rich inmates from two prisons in Jiangxi Province of China were chosen as interview subjects [33]. The requirements for inclusion in the group of burglary offenders must be at least 18 years old. Subjects who had experienced mental illness or were currently experiencing an episode of mental illness, as well as subjects with severe traumatic brain injury and brain disease were excluded.

Basic information about the subjects of the study: There are 10 women (coded F1 to F10) and 31 men (coded M1 to M31). The mean age of the subjects was 40.46 ± 9.06 years, with males having a mean age of 41.97 ± 8.53 years and females having a mean age of 35.18 ± 9.25 years. 19 people obtained an elementary school education, representing 46.3% of the total number, 19 people had junior high school education, representing 46.3% of the total number, 1 person had a high school education, representing 2.4% of the total number, and 2 people had university education or higher, representing 4.8% of the total number. There were 21 rural residents, representing 51.2% of the total population, and 20 urban residents, representing 48.8% of the total population. There were 5 first-time burglars, representing 12.2% of the total, and 36 multiple burglars, representing 87.8% of the total. There were 11 drug addicts, representing 17.7% of the total population.

Initially, an interview outline was developed. The interview outline included family environment and parenting style, growth experience, employment history, financial status, history of substance abuse, criminal history, and burglary behavior. A semi-structured interview outline containing 38 questions was the result of multiple stages of development, including a first draft, expert feedback, a pre-interview, and a supervisor’s approval.

Second, the pre-interview preparation work. The basic information and criminal history of the interviewees were initially determined by retrieving their sentence files, which included registration forms, indictments, and judgments. Before the formal interview, the interviewee was asked for permission to record the entire conversation and to sign a consent form.

Third, in-depth interviews were conducted. During the formal interview, the researcher and interviewee engaged in in-depth, one-on-one conversations. Based on the respondent’s responses and emotional state, the researcher modified the interview’s questions and sequences, and even paused or ended the interview. As compensation for the study, daily necessities were provided following the interview.

2.2.2 Data Processing and Analysis

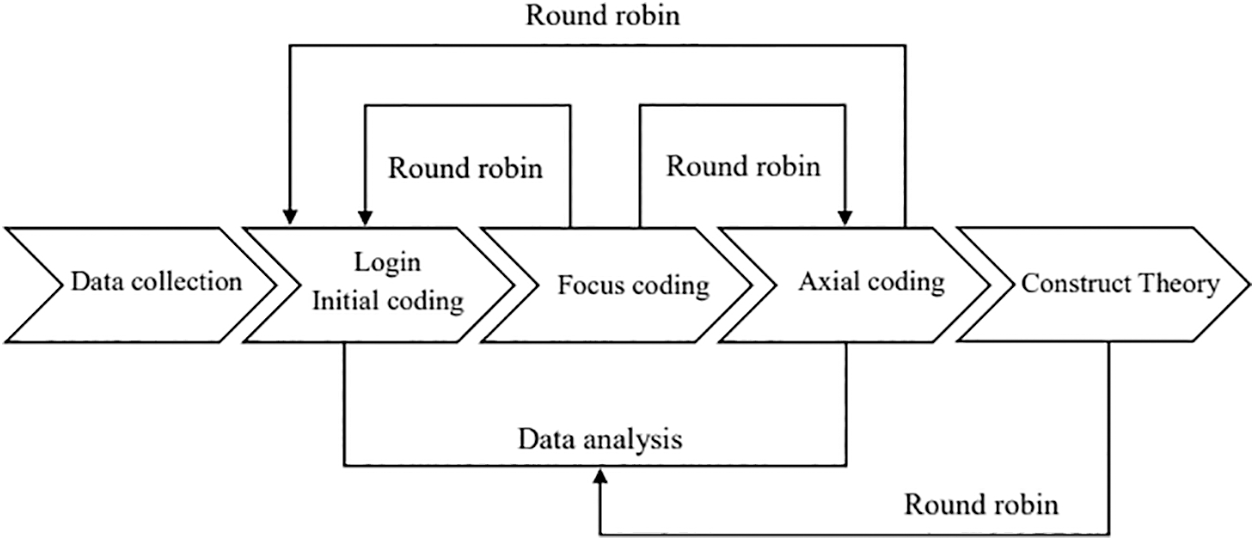

The grounded theory was adopted to collect, analyze, and theoretically construct the raw materials [34]. The processing and analysis of data were divided into three sections: (1) Audio data collection and text transcription. (2) Textual data tertiary coding. (3) The generation and testing of theories [35].

Following the above steps, 41 subjects were interviewed for a total of 67 h, and each interviewee spent approximately 80 to 100 min with the researchers. The collected speech data were imported using Nvivo 11.0, and the non-numerical, unstructured textual data were indexed and theorized to create a 380,000-word draft verbatim [36]. The textual material was accordingly coded at the first, second, and third levels. Three researchers participated in the discussion during the entire coding process, including a professor, a lecturer, and a postdoctoral fellow, to ensure the objectivity of information extraction. Firstly, the postdoctoral researcher analyzed the manuscript word by word, stating the sentences and paragraphs of the same question objectively and completely. The first level of encoding is to convert these similar statements into generalized items (a1, a2, a3…), that is, the initial encoding. Afterward, the lecturer and researchers extracted semantic repetitions and similar expressions from the first-level codes and merged them, and then separated and classified the compound semantic words based on a comprehensive analysis of the remaining independent entries, identified and established the relationships between the first-level codes, summarized, integrated, and named the first-level codes (A1, A2, A3…), i.e., the second-level codes (focused codes). Lastly, the postdoctoral researcher extracted the core concepts from the secondary coding and named them (B1, B2, B3…) [37], which was the tertiary coding (axis coding). To ensure the independence and scientific validity of the items, three researchers reviewed and summarized the above items and extracted the influencing factors and psychological evolution process of theft from the logical relationship between the core concepts and other items. Fig. 1 displays the particular research procedure.

Figure 1: Flow chart of data analysis

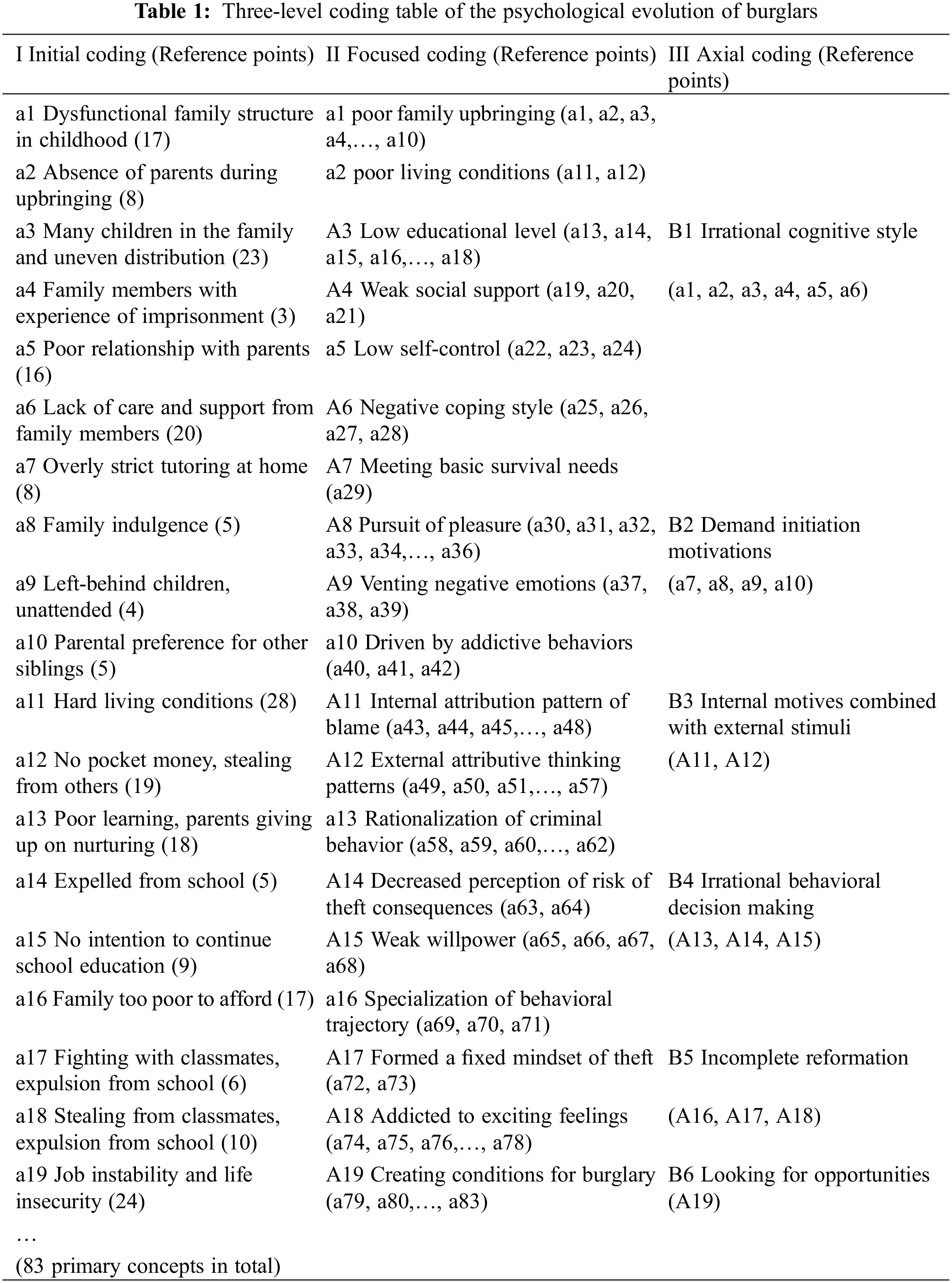

The extracted, analyzed, and organized word-by-word transcribed text yielded a total of 748 reference points. Each piece of information was conceptualized, and 83 initial codes were extracted, including parental absence during childhood (a2), difficult living conditions (a11), unstable job and insecure life (a19), lack of self-control (a54), lack of legal awareness (a66), and careless friendships (a83) (a73). The interview materials were reorganized based on the results of the initial coding, with the 83 initial codes summarized into 19 focus codes. The core concepts were extracted from the focused codes during the selection coding phase to form six axial codes (see Table 1).

3.2 Analysis of the Elements Influencing Burglary Behavior

Diverse influencing factors have led to a complex situation in the interpretation of the psychology of burglary.

To increase the study’s explanatory power and generalizability, semi-structured interviews were used to systematically delve deeper into the factors that influence individual burglary. By sorting the core concepts and other items in logical relationships, it was determined that the factors influencing burglary behavior consisted of six major components: burglary cognition, burglary motivation, burglary decision-making, delinquent peers, burglary opportunity, and incomplete reformation.

In the generation of burglary behavior, burglary cognition plays a pioneering role. The unreasonable cognition of burglars manifests itself primarily in the following aspects: (1) Inappropriate self-positioning. Intruders frequently attributed their criminal behavior to a lack of self-control, an inability to overcome their desire for money, and the influence of drug (gambling) addiction. (2) Externally attributed model. Respondents emphasized external factors as the primary cause of their own criminal behavior. (3) Rationalization for burglary. Some interviewees viewed burglary as a way to “rob the rich to help the poor” and minimize the victim’s suffering. (4) Disregard legal consequences. Some interviewees stated that they cared more about the immediate benefits of burglary than the legal repercussions.

Motivation for burglary is the internal driving force behind the commission of a burglary. The interviews revealed that burglars’ primary motivations fell into four categories: (1) Meet basic living needs. Some of the interviewees lived in extreme poverty and improved their lives through burglary. (2) Seek pleasure. Some burglars were greedy for pleasure, burglary has become the lowest-cost means to eat, drink, and entertain. (3) Revenge in society. Some burglars vented their dissatisfaction with society by violating other people’s property. (4) Addictive conduct (drug use, gambling, etc.). Individuals are under the control of addictive behavior and indirectly satisfy the addictive behavior by stealing sufficient funds.

According to interviewees, burglary is preceded by analysis, evaluation, and selection of burglary behavior, i.e., burglary decision-making. The decision to commit a burglary is influenced not only by the external environment and the timing of the crime, but also by the offender’s personality traits, cognitive level, personal experience, and other internal factors. For instance, interviewee M7 stated that: “I used to enjoy gambling and owed a lot of money to others. Once I went out to dinner with a friend and heard that all of the valuables in his house were kept in a safe. It was my intention to steal the safe. Before opening the safe, I checked online what tools are available for prying it open.” The investigation results show that burglars plan to purchase the master key, the hanging rope, the window chisel hammer, and some other theft tools. To accurately identify the target of the crime in the nearby community, and to avoid the peak of the flow of people, a clear monitoring range must be established from the monitoring dead end into the residence. They also gave adequate consideration to the time of the crime, the method of operation, and the escape route. It should be noted that the recidivist of burglary is more decisive and resolute in behavior decision-making than the first offender based on his rich experience in burglary, and his “success rate” of burglary is higher.

Delinquent peers emphasize the influence of peer groups on burglary. Peer groups are more attractive and influential to individuals who enter society at a younger age, and their group norms and values are crucial to the socialization of individuals. In general, groups at the bottom of the social hierarchy are susceptible to subcultures. Long-term exposure to their value system may result in the development of deviant behavior. Most burglars are unable to obtain a positive acknowledgment from the dominant culture and turn to subcultures to find their own values as a result of structural family dysfunction, economic hardship, and academic failure. This study found that the majority of burglars committed their crimes in groups comprised primarily of their peers, demonstrating the influence of bad peer groups on individual burglary behavior.

Burglary opportunity refers to the potential criminal’s search for an appropriate occasion to commit a crime. Inadequate supervision of daily living environments or objects and security system flaws create ideal conditions for burglars and prompt the occurrence of burglary. In addition, burglars plan ahead and select cunning times to avoid the supervision of others, destroy the surveillance system, or with the help of others to keep a lookout to complete the burglary successfully.

Incomplete reformation is the root cause of the high recidivism rate associated with property theft. Several studies have demonstrated that the concept of delinquency significantly influences the recidivism of released prisoners [38]. As proved by the survey results, the majority of recidivists have a low level of education, an inability to distinguish between right and wrong, good and evil, a profound subjective evil, and a psychology of getting something for nothing while ignoring the law; therefore, prison reform is insufficient to convince them of the gravity and harm of their crimes. It is easy to take the risk of committing crimes again after returning to society and encountering discrimination or other obstacles.

3.3 The Psychological Process of Burglary Formation

3.3.1 Cognitive Formation Stage

According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, the interaction of innate genetics and acquired environment influences cognitive formation [39]. The interviewers revealed that the environment of one’s upbringing, one’s life experiences, and one’s personality traits play a significant role in the cognitive formation of an individual burglar. Concerning the growth environment, the majority of respondents reported dysfunctional family structure during childhood (a1) and inappropriate family parenting style (a2) (a7). School and social experiences were included in life experiences. They had generally poor academic performance (a13) and poor relationships with classmates during their school years (a17). Individuals lack stable jobs and income (a19), are not respected by others (a20), and even complain about unfair social allocation (a21). Some individuals gradually develop hostility toward society and others and pathological thoughts of revenge against society in the space between reality and their dreams (a25). In terms of individual personality characteristics, burglars tend to be impulsive (a21), risk-taking (a23), and emotionally unstable (a24). Individual perceptions gradually deteriorate as a result of the interaction of negative upbringing, disillusioning life experiences, and negative personality traits, resulting in the germination of a seed that teeters on the edge of morality and law.

3.3.2 Motivational Dominance Stage

Under the influence of negative cognition, the urge to steal is triggered in varying degrees by different individuals [40]. Some interviewees assert that inadequate social assistance and severely-ill family members compel them to steal to meet their basic needs (a29). Some interviewees are dissatisfied with their boring life and seek corrupt pleasure through burglary (a30). Long-term exposure to negative influences has ended in a deformed antisocial personality, the violation of moral and legal boundaries, and making use of burglary to express their dissatisfaction with society and real life (a38). Even those whose pathological needs are driven by addictive behaviors such as drug abuse, gambling, and kleptomania have been known to steal others’ properties (a41). At this stage, burglary motivation caused by different needs is the most direct force affecting individual burglary behavior.

3.3.3 Behavioral Decision-Making Stage

At this stage, the majority of respondents have irrational decision-making preferences prior to committing a crime, i.e., they make irrational behavioral predictions based on the integration of multiple pertinent data. After the motivation for burglary becomes apparent, individuals typically evaluate whether to commit a crime, how to commit a crime, the benefits of the crime, and the repercussions of the crime. Yang et al. [41] discovered that individual psychological characteristics and risk context variables have a significant impact on the decision to commit a crime. Some interviewees highlighted an inability to self-regulate emotions when confronted with unexpected events (a45), risk-taking and impulsive behavioral traits (a43), and a preoccupation with immediate benefits. Individuals have a tendency to justify burglary (a63) and attribute criminal behavior to external factors such as poor life circumstances (a52) and low social inclusion (a55). After individuals are exposed to extreme cognition and inappropriate motivational cues, irrational coping styles drive behavior to the verge of delinquency. Compared to first-time burglars without practical experience, the recidivists of burglary are more composed during the behavioral decision-making stage, specialize in theft methods, and gradually improve their anti-surveillance ability (a67). Quite a few recidivists of burglary even enjoy the thrill of committing crimes (a75).

3.3.4 The Psychological Evolution of Burglars

The burglary is not achieved overnight, but a process of mutual influence of cognition, motivation and behavior. In the case of first-time burglaries, the psychological evolution of burglary proceeds is as follows: burglary cognition, burglary motivation, and burglary behavior. According to the majority of burglars, a lack of family education and negative school experiences during childhood motivate individuals to want to escape from such a trap. Due to a lack of desirable social skills, entering society at a young age makes it difficult to obtain a desirable job and compensation. Long-term, under severe economic pressure and actual oppression, individuals are susceptible to criminal behavior if they are inducted or stimulated by undesirable peers. Consequently, early adverse experiences can easily result in cognitive deficits and an inability to tell right from wrong. The motivation to commit burglary stems from real needs or the influence of others, and burglaries arise when a suitable opportunity presents itself.

In this study, recidivists of burglary accounted for 87.8% of the total number, which confirmed once again the high recidivism rate of burglary crimes in China. Why do burglars relapse after completing rehabilitation? This issue appears more pertinent for investigation. According to interviews with recidivists, incomplete correction of offenders is a significant reason why individuals commit crimes again. For instance, recidivism M3 stated that: “When I went to prison, I was surrounded by people who were good at burgling, and when they were free, they were talking about what they had stolen, how they had stolen it, how they were going to protect themselves from the police. Some of my friends agreed to commit burglary together after they got out of prison.” Recidivism F5 stated that: “I am addicted to drugs. My main objective is to make money, whether it is by stealing or robbing. Anyway, I would like to make money and purchase drugs”. Not only did she not repent while serving her sentence, but she also held a grudge against the public security police, and she was determined to exact revenge. It is evident that a negative rehabilitation experience has a direct effect on a person’s burglary motivation. Recidivists of burglary exhibit a marked antisocial behavior in contrast to first-time burglars. Recidivists of burglary possess a calmer mentality, more skilled burglary techniques, more vigilance to the external environment, and improved anti-reconnaissance methods due to previous burglary experience. As time has passed, the manner in which burglaries committed has changed from independent action in the early stages to committing crimes in partnership with others, from accessory to principal, etc. Changes in the method of burglary and in burglary behavior reflect the process of recidivism from being unskilled in the methods of burglary at the beginning to gradually becoming professional in the methods of burglary over the course of time. Additionally, this is a manifestation of the motivational changes occurring during the behavioral decision-making stage of recidivism. The recidivists of burglary stole more money, the antisocial personality gradually developed, and the individual even normalized their burglary behavior. Contrary to initial burglaries, recidivism results from a change in motivation stemming from the act of burglary. The burglary motivation affects burglary cognition, and burglary cognition determines the burglary behavior process. In conclusion, the psychology of burglary is the interaction between cognitive formation, motivation dominance, and behavioral decision-making (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Psychological evolution and axial coding distribution of burglary crimes

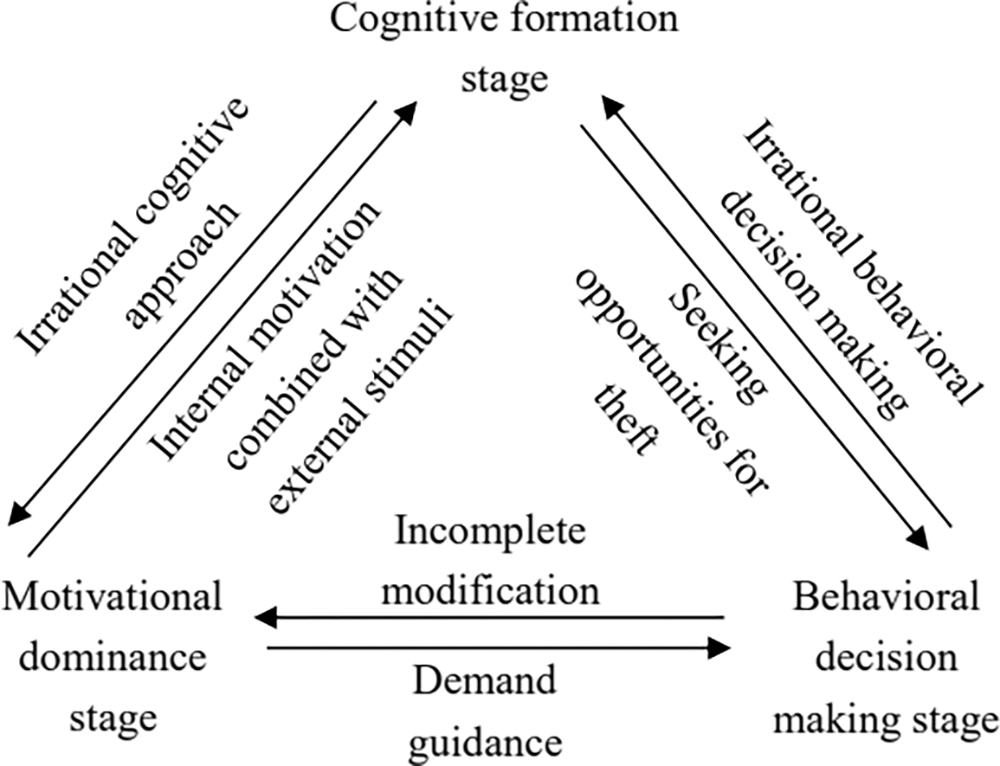

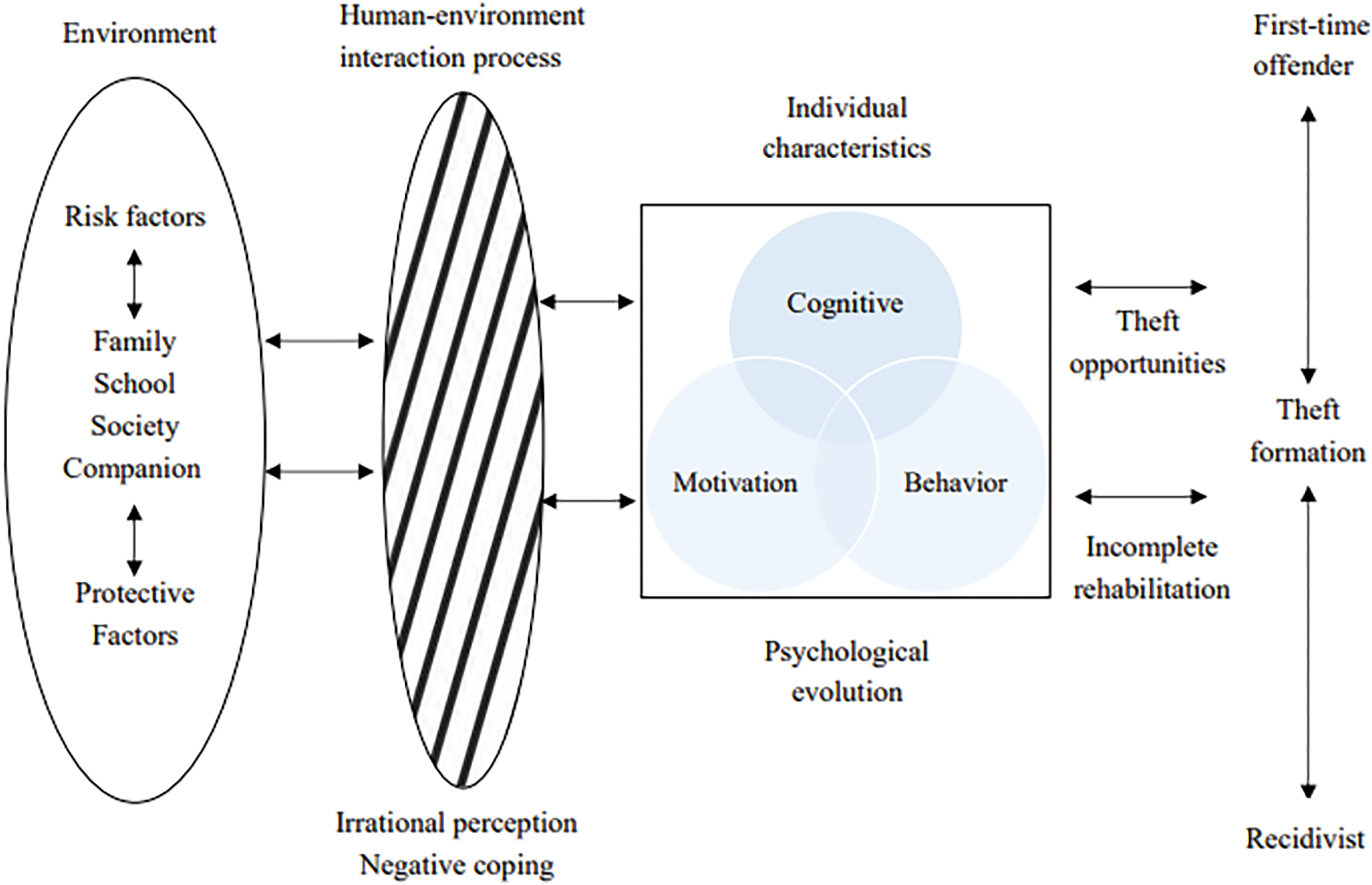

3.4 Explanatory Model of the Psychological Mechanism of Burglary Crimes

According to the theory of ecosystems, individuals do not passively accept the influence of their environment, but rather actively interact with the outside world and construct their own world. This paper attempts to construct an explanatory model of the psychological mechanism of burglary by integrating the risk factors influencing burglary with the psychological evolution process (see Fig. 3). The model is framed by a dynamic change process along the lines of human-environment interaction and consists of three components: (1) Risk factors and protection factors from the environment. (2) The subject characteristics of burglars. (3) The individual reaches a negative developmental outcome alongside life adversity as a result of numerous dynamic processes that mediate between the individual and the environment and the outcome. Specifically, this includes environmental history, adverse experiences, individual traits, behavioral outcomes, and the dynamic processes of interaction between the environment and the individual, and the individual and the outcome.

Figure 3: Explanatory model of the psychological mechanism of burglary

Specifically, adverse environmental factors (e.g., family, school, society, etc.) can disrupt an individual’s internal dynamic equilibrium and lead to thoughts of burglary. Once the risk factor, which is essential for the individual’s development, outweighs the protective factor, the individual actively or passively attempts to confront the dilemma, explain and overcome it, and create a safer environment. In other words, when individuals are exposed to a series of negative circumstances, such as dysfunctional family structures, inappropriate family upbringing, poor education, poor friendships, and lack of material security, the desire to commit crimes is intensified. The dynamic interaction between the individual and the environment, in which the individual’s characteristics transform an unfavorable environment into a more dangerous outcome. For instance, the perception that burglary is an improvement to one’s material life. Cognitive deconstruction reinforces the irrational belief that burgling is a means of achieving a more equitable distribution of wealth in society. After release from prison, friendship with delinquent peers who conspire to commit burglary. Negative coping, conforming to adversity rather than attempting to alter their lives through their own efforts. Individual characteristics, including burglary cognition, burglary motivation, burglary decision-making. Individuals rationalize their motivation to burgle based on extreme cognitive styles when confronted with an unfavorable situation, and when they perceive that the benefits of burgling outweigh the costs, they are likely to act on their inner thoughts once fetch a suitable opportunity to burgle. Intruders are categorized as first-time burglars or the recidivists based on whether they commit burglary again after their release from prison. Individuals repeat criminal behavior due to insufficient reformation and entrenched criminal attitudes. In conclusion, burglary is a comprehensive and dynamic consequence of the individual’s internal and external factors.

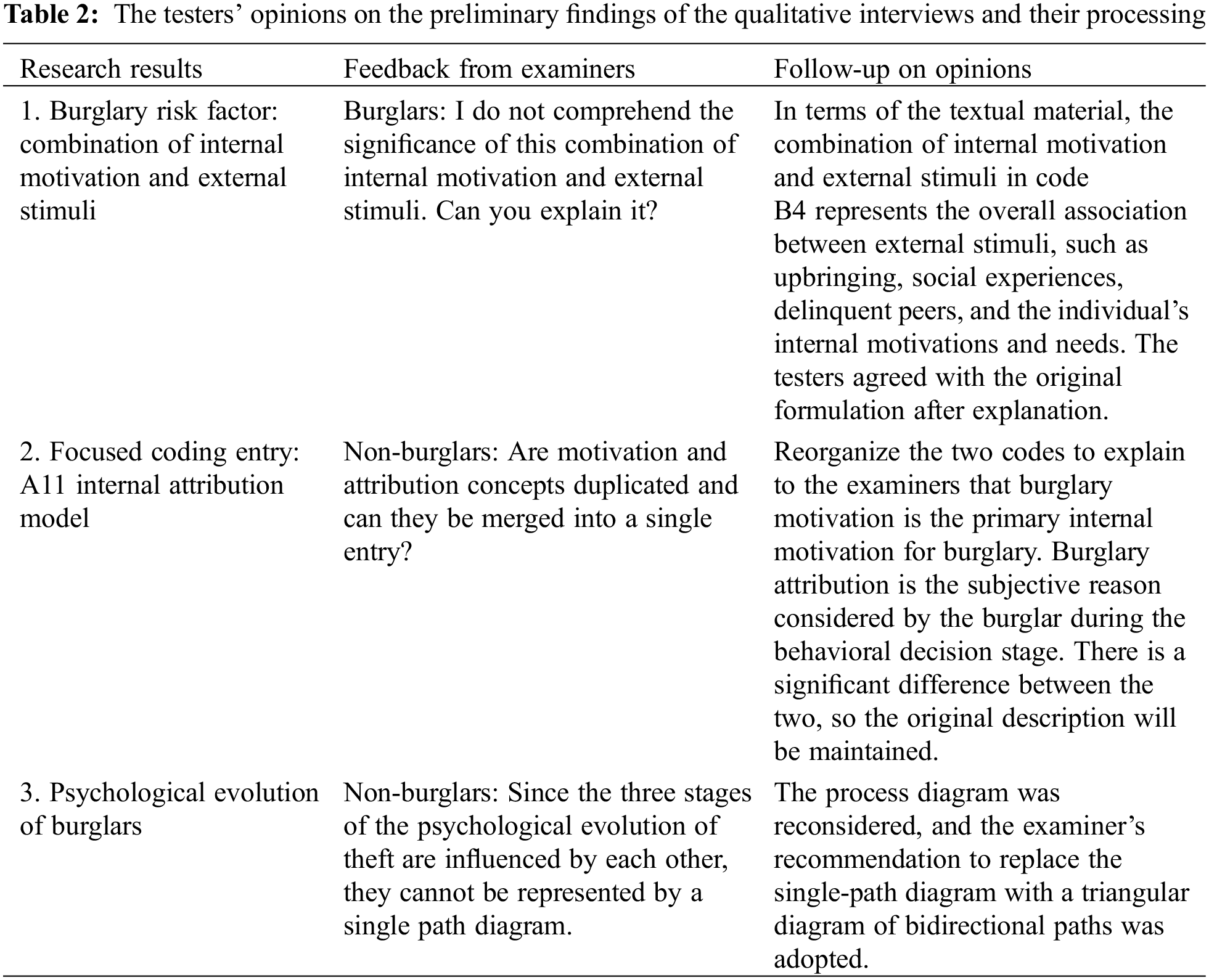

In contrast to quantitative studies, qualitative research results can extrapolate from sample characteristics to general characteristics. Numerous researchers have employed “validity” tests to determine the dependability of qualitative research findings. This study employed participant and nonparticipant validity tests to evaluate the dependability of coding results, psychological evolutionary processes, and explanatory models of burglars’ psychological mechanisms.

4.1 Validity Tests of Participants and Non-Participants

Participant testing is the feedback of coding results to the study’s participants after the researcher has repeatedly read, labeled, coded, classified, and extracted themes from the transcribed textual material. To prevent bias in the research findings resulting from the researcher’s subjective assumptions, validity testing was conducted in terms of both description and interpretation. From the study population, four burglars of different genders, educational levels, and occupations were selected to provide feedback on the coding results.

The non-participant test is to feedback the preliminary results of the study to other subjects who did not participate in the study. Four burglars who did not participate in this interview were selected from prison A and prison B. In addition, two PhDS, one of whom was a criminal psychology PhD, were invited to make comments and suggestions on the study’s findings.

These 10 examiners’ comments were summarized (see Table 2). When the testers’ feedback was consistent with the study’s initial findings, the initial findings were kept. In the contrary scenario, this section was repeated for validation. In this instance, the original source material is reviewed to assess the adequacy of the basis for the distillation of this result. If the reliability of this result can be demonstrated, the original conclusion is maintained; otherwise, it is modified based on the testers’ feedback [42].

A comparison of the test results from participants and non-participants revealed that the feedback from the eight burglars represented the perspective of “crime perpetrators,” whereas the feedback from the two normal people represented the perspective of “crime interpreters.” The feedback dissected the psychological evolution of the burglars from multiple perspectives, which significantly improved the validity of the qualitative findings.

4.2 Validity Risk in Qualitative Research

The first thing is the associated validity risk with purposive sampling. Qualitative research emphasizes the population’s representativeness. In order to ensure the validity of the sampling, police officers in the prison area were fully informed of the purpose of the study prior to the selection of interviewees. In an effort to maximize interview data, typical burglars were chosen as study subjects with the assistance of the police.

Secondly, the risks associated with the researcher’s perspective as a “crime interpreter” in terms of validity. To fully investigate information regarding burglary, the researcher must earn the full confidence of the respondent. Prior to the formal study, the researcher conducted a number of legal lectures and group counseling sessions in the prison, which diminished the interviewees’ sense of unfamiliarity and apprehension towards the researcher.

Again, there was a risk of validity associated with the process of material collection and text analysis. In this regard, prior to the formal interview, the researcher had multiple conversations with the prison warden and the head of the education section to gain a foundational understanding of the burglars and their offenses. For a full restoration of the true crime process, the researcher maintained a neutral and objective attitude during the interviews and communicated in the language that was familiar to the burglars.

5.1 Psychological Evolution of Burglars

The stages of a burglar’s psychological development are cognitive formation, motivational dominance, and behavioral decision-making. Individuals exhibit distinct psychological characteristics based on their developmental stage. The following discussion focuses on the impact of these psychological traits on criminal behavior.

For the cognitive formation stage, the results of the study revealed that the vast majority of respondents lived in difficult circumstances during adolescence, in families with financial difficulties, and achieved a low education level on average. The parents of burglars have a polarized parenting style that is either overly strict or overly permissive. In a study of 599 school-aged children, Prinzie et al. [43] discovered that negative family parenting styles were a significant factor in the development of poor cognition. According to a study conducted by Zheng et al. on adult male burglars, inconsistent parenting styles were associated with the development of delinquent behavior and delinquency problems [44]. The family is where a person’s socialization begins and has a profound and lasting impact on his or her life. Love and emotions within the family are essential for the development of a healthy personality and the acquisition of good character in individuals. This interview revealed that the parents of burglars are unable to fulfill their educational responsibilities due to financial, parental bias, or capacity constraints. Individuals’ perceptions are easily skewed due to a lack of proper restraint and discipline, their limited ability to distinguish right from wrong, and the influence of bad habits and desires.

Motivation is the premise of individual behavior during the stage of motivation dominance. Motivation is the driving force that produces behavior, and it is the primary internal motivation that causes behavior, maintains behavior, and directs behavior towards a particular goal [45]. The loneliness and helplessness inside, after repeated setbacks in employment, emotions, family, and other aspects, it is very easy to become hostile to society and develop the psychology of revenge. Under such circumstances, it is quite easy to generate burglary motivation when coming across a bad person, plus embarrassed material needs. Motivation can push an individual from a state of rest to action [46]. The motivation for burglary dominates the cognitive formation and behavioral decision-making stages in this study. Under the influence of undesirable thoughts, it rouses individuals in a resting state and propels them into a state of behavioral activity. The strong motivation of burglary encourages individuals to take risks and to gradually approach the decision-making stage where burglary occurs.

Burglary is the consequence of burglary-related choices. As a result of their limited rationality, burglars are only able to consider one or a few of the factors when determining whether or not to burgle. The study conducted by Lerner revealed that negative personality, impulsivity, and emotionalism are associated with high-risk behavior [47]. Guo et al. [48] also discovered that individuals with impulsive characteristics have enhanced responses to immediate reward signals and decreased responses to delayed punishment signals during behavioral decision making. This partially explains why the burglars in this study disregarded legal and moral constraints and pursued a life of crime. In general, burglars lack self-control and are risk-taking and impulsive. The motivation of burglary and the influence of irrational behavioral decisions make it simple for individuals to pursue delinquency for immediate benefits. In contrast to typical thieves, burglars usually have a more comprehensive criminal plan in mind when making their behavioral decisions. Several researchers have examined the factors that influence the burglar’s choice of target [49]. A recent study concluded that when burglars are looking for the best target, they consider the target and various environmental variables surrounding it, try to enter the house with a shorter and more convenient path, and plan how to clear out all obstacles which may prevent them from entering the house, and stole more valuable items as much as possible [50]. Crimes of theft can be committed at various times depending on the type of theft [51]. In general, pickpocketing occurs between 10 a.m. and noon, as well as between 3 p.m. and 6 p.m., when commercial activities are relatively busy. Most burglaries occur between 9:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m., between 3:00 p.m. and 5:00 p.m., when people go to work, and during sleep between 12:00 a.m. and 3:00 a.m.

The aforesaid three stages of psychological evolution of a burglar reflected the interrelationship among the needs, motivations, and actions. The Maslowian theory of motivation states that when needs reach a certain level and they can be met in a timely manner, the needs will transform into motivation, which then controls the behavior of the individual [52]. In the process of growing up, burglars are affected by poor family upbringing, low education level, and weak social support, which result in individual self-cognition defects and promote the formation of the initial stage of burglary. A stage of motivational dominance is the stage in which cognitive defects in burglars influence the development of the burglary personality. Personality characteristics such as impulsivity, poor self-control, and hedonism result in different material and spiritual needs in an unfavorable growth environment. In order to meet different needs, individuals create an incentive to burgle. At the final stage of behavioral decision-making, the burglar waits for the right moment to burgle, it is therefore necessary to adopt a suitable burglary plan in order to commit the crime.

5.2 Psychological Mechanisms of Burglary Crimes

Based on the interaction between human and environment, this study develops a model to explain the psychological mechanisms of burglary offenders. This study contends that the psychology of burglary crimes is the product of a dynamic and all-encompassing nature. The synthetic agent theory of crime proposed by Luo Dahua contends that the individual crime causation system is an integrated, dynamic result of the combined action of psychological and behavioral factors, which is consistent with the perspective of this study.

The internal and external factors that contribute to the causes of crime are interconnected and interactive. The act of burglary is the result of the interaction between a person’s negative psychological traits and an unfavorable external environment. Children with a lack of moral and legal awareness, emotional apathy, and a skewed mindset may be the result of inadequate family and school education. All of these give children opportunities to become delinquent. The disparity between reality and ideal creates tension within individuals. On the one hand, the beauty of modern society fills their imaginations with visions of a happy life, while on the other, their desire for a better life is obstructed by the harsh reality. In the conflict between desire and reality, hope and disillusionment, the stimulation of negative peers or surroundings piques their interest in the unknown world. In the absence of the ability to distinguish right from wrong and self-control, their inner desires are likely to exceed the bottom line of morality and law in certain situations or conditions, and to be satisfied by the most extreme method of burglary when given the chance. When a burglar commits his first offense, he possesses one or more personality flaws and a disconnect between his understanding and evaluation of society and the objective reality. If reformation is incomplete, negative psychological traits will be reinforced. When they return to society and are confronted with the harsh reality of life, it is easy for them to commit crimes again.

As a typical property crime, burglary has existed since ancient times and has been one of the crimes that successive dynasties had vigorously surpressed. Its incidence rate is significantly higher than other types of crime and poses a significant threat to social security. Punishment and burglary crime prevention must be based on a thorough comprehension and scientific analysis. In-depth interviews with 41 burglars revealed that a deprived upbringing is a fertile ground for the development of burglary attitudes. Peers are the catalyst for the development of perceptions of theft. Individuals shift from a static mental state to a behavioral state when they are highly motivated to commit burglary. When a person perceives that the benefits of committing a crime outweigh the costs, he or she becomes determined to burgle. In order to complete the burglary successfully, the individual takes the initiative to create a burglary-friendly environment, i.e., opportunities for burglary. Incomplete correction is a significant factor in recidivists’ recidivism. Briefly, the psychology of burglary consists of cognitive formation, motivational dominance, and behavioral decision making, and is the result of dynamic human-environment interaction. These findings provide a new perspective for burglary crime research and an empirical foundation for the reduction of burglary.

In the future, we can establish a diverse social supporting system, including prisons, communities, and families; improve the psychological cognition level of burglary prisoners; assist them in actively complying with the reforms during their imprisonment; enhance the utilization of social supporting services; help them to take positive coping measures to cope with setbacks and difficulties in life in the future; encourage the family members and friends to visit the prisoner; encourage communication between prison guards and inmates; encourage family members, friends, prison guards, and inmates to provide care that they can feel; besides improving the mental heath of burglars, we should also facilitate their smooth return to society and prevents recidivism in the long run.

This study has the following limitations, which will be addressed in future research: To begin with, the limitations of sampling. Given the specificity of the offender population, this sample was drawn solely from men’s and women’s prisons in a certain province, which is insufficient to represent the basic situation of all burglars. The locality has an effect on the study’s results, reducing their representativeness. According to the geographical distribution of the sample, the sample of burglars should be expanded to include more countries in the future. Second, the study’s design limitations. Even though the results of the study’s validity test were satisfactory, the study’s scientific rigor and the reliability of its findings would have been enhanced if a combination of quantitative and qualitative research had been used to collect data. Lastly, future research can develop and test the efficacy of individualized group counseling or case counseling programs that match the causal needs of different burglars.

Funding Statement: Supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC0831002).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. National Bureau of Statistics (2019). China statistical yearbook. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press. [Google Scholar]

2. Jin, G. F., Shou, J. L., Lin, X. N. (2019). Analysis and forecast of crime situation in China (2018–2019). Journal of the Chinese People’s Public Security University (Social Science Edition), 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

3. Park, S. Y., Lee, K. H. (2021). Burglars’ choice of intrusion routes: A virtual reality experimental study-science direct. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74(4), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

4. Thrush, M. A. (2016). Book review: Rural crime and community safety. Contemporary Rural Social Work Journal, 8(2), 113–115. [Google Scholar]

5. Yan, J. H., Hou, M. M. (2020). Research on time series prediction of theft crimes based on LSTM network. Data Analysis and Knowledge Discovery, 4(11), 84–91. [Google Scholar]

6. Xiao, L., Liu, L., Song, G. (2018). Journey-to-crime distances of residential burglars in China disentangled: Origin and destination effects. International Journal of Geo Information, 7(8), 325–329. DOI 10.3390/ijgi7080325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Qu, X. G., Ruan, Q. L., Zhang, L. (2008). Criminal law. Beijing, China: China University of Political Science and Law Press. [Google Scholar]

8. Chen, Y. (2021). The criminalization standard and criminal form of burglary. Western Journal, 1, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhao, B. Z., Wang, Z. X. (2010). Anglo american criminal law. Beijing, China: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

10. Zhang, M. K. (2006). Japanese criminal code: 2006 edition. Beijing, China: Law Press. [Google Scholar]

11. Zhang, M. K. (2007). Outline of foreign criminal law. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press. [Google Scholar]

12. Ren, T. (2021). The doctrinal analysis and judicial determination of multiple burglaries. Academic Communication, 3, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

13. Wang, J. (2021). The objective construction of property interest theft. Politics and Law, 3, 40–56. [Google Scholar]

14. Peng, W. H. (2021). An empirical study on the standardization of sentencing for theft. Journal of East China University of Political Science and Law, 24(2), 101–113. [Google Scholar]

15. Xu, F. M. (2002). On the mechanism of crime generation–A sociological analysis of crime generation. Chinese Journal of Criminal Law, 1, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

16. Dahua, L. (2003). Criminal psychology. Beijing, China: China University of Political Science and Law Press. [Google Scholar]

17. Davies, T., Johnson, S. D. (2015). Examining the relationship between road structure and burglary risk via quantitative network analysis. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 3(3), 481–507. DOI 10.1007/s10940-014-9235-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Clarke, R. V. (1980). Situational crime prevention. Crime and Justice, 20(2), 91–150. [Google Scholar]

19. Bernasco, W., Nieuwbeerta, P. (2005). How do residential burglars select target target areas? A New approach to the analysis of criminal location choice. British Journal of Criminology, 48(4), 124–127. [Google Scholar]

20. Apel, R. (2012). Sanctions, perceptions, and crime: Implications for criminal deterrence. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

21. Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J. (2010). The psychology of criminal conduct. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

22. Ding, Y., Zhang, Q., Lu, H. (2017). A survey of personality disorder tendencies among male offenders in custody. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 27(5), 331–333. [Google Scholar]

23. Ge, W. Y. (2018). A survey of personality disorder co-morbidity among adult male inmates and its influencing factors (Master Thesis). Nanjing Normal University, China. [Google Scholar]

24. Yang, Y. Z. (2018). A study on the relationship between personality characteristics of offenders and family parenting style (Master Thesis). Changjiang University, China. [Google Scholar]

25. Fu, J. H., Tao, X. H. (2016). Analysis of the mediating effect of narrative disorder between childhood abuse, coping style. Advances in Psychology, 6(3), 248–254. DOI 10.12677/AP.2016.63032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Thimm, J. C. (2010). Mediation of early maladaptive schemas between perceptions of parental rearing style and personality disorder symptoms. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 41(1), 52–59. DOI 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. de Wit, H., Flory, J. D., Acheson, A. (2007). IQ and nonplanning impulsivity are independently associated with delay discounting in middle-aged adults. Personality & Individual Differences, 42(1), 111–121. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2006.06.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Morrice, C. L. (2020). Potential uses of ultrasound in investigation and management of the burglars from home alone. Academic Emergency Medicine, 3, 245–148. [Google Scholar]

29. Ling, S. C., Amerudin, S., Yusof, Z. M. (2020). A spatial analysis of the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics with burglar behaviours on burglary crime. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

30. Sanders, A. N., Kuhns, J. B., Blevins, K. R. (2016). Exploring and understanding differences between deliberate and impulsive male and female burglars. Crime & Delinquency, 63(12), 1547–1571. DOI 10.1177/0011128716660519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bechara, A., Dolan, S., Hindes, A. (2002). Decision-making and addiction (part IIMyopia for the future or hypersensitivity to reward? Neuropsychologia, 19(5), 652–663. DOI 10.1016/S0028-3932(02)00016-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wu, J. X., Huang, X. T. (2012). A preliminary investigation of integrity structure. Journal of Psychology, 44(3), 354–368. [Google Scholar]

33. Chen, X. M. (2000). Qualitative research methods and social science research. Beijing, China: Educational Science Press. [Google Scholar]

34. Kathy, K., Bian, G. Y. (2009). Constructing rooted theory: A practical guide to qualitative research. Chongqing, China: Chongqing University Press. [Google Scholar]

35. Guo, R. (2016). A study of factors influencing family well-being based on rootedness theory (Master Thesis). Nanchang University, China. [Google Scholar]

36. Zhang, X. M., Yang, L. P. (2018). A qualitative exploration of human-god attachment relationship in christian prayer process. Journal of Psychology, 50(1), 115–129. [Google Scholar]

37. Kathy, K., Bian, G. Y. (2009). Constructing rooted theory: A practical guide to qualitative research. Chongqing, China: Chongqing University Press. [Google Scholar]

38. Luo, Y. H. (2013). Research on the personality characteristics and behavior of criminal groups (Ph.D. Thesis). Central South University, China. [Google Scholar]

39. Ribaupierre, A. D. (2015). Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition), 3, 120–124. DOI 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.23093-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen, Y. (2006). A study of motivation in modern chinese study abroad education (Master Thesis). Northeast Normal University, China. [Google Scholar]

41. Yang, F., Lan, Z. (2019). Problems and solutions to the reasoning of criminal sentence in China: Analysis of the criminal sentence of local basic courts as an example. Nanjing Journal of Social Sciences, 7, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

42. Zhang, X. M., Yang, L. P. (2018). A qualitative exploration of human-god attachment relationships in christian prayer processes. Journal of Psychology, 50(1), 115–129. [Google Scholar]

43. Prinzie, P., Onghena, P., Hellinckx, W. (2010). The additive and interactive effects of parenting and children’s personality on externalizing behaviour. European Journal of Personality, 2, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

44. Zheng, Y., Liu, X. H. (2010). Research on parental rearing patterns and family dynamics of male thieves. Journal of Sichuan University: Medical Edition, 41(6), 1047–1050. [Google Scholar]

45. Perkins, D. D., Meeks, J. W., Taylor, R. B. (1992). The physical environment of street blocks and resident perceptions of crime and disorder: Implications for theory and measurement. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12(1), 21–34. DOI 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80294-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Peng, D. L. (2001). General psychology (Revised Edition). Beijing, China: Beijing Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

47. Lerner, J. S., Keltner, D. (2000). Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cognition & Emotion, 38 (4), 315–326. DOI 10.1080/026999300402763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Guo, X., Song, P., Zhao, H., Zhang, F., Wang, Q. L. et al. (2017). The characteristics of face recognition of psychopathic violent criminals. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 25(4), 591–596. [Google Scholar]

49. Hanayama, A., Haginoya, S., Kuraishi, H., Kobayashi, M. (2018). The usefulness of past crime data as an attractiveness index for residential burglars. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 15(3257–270. [Google Scholar]

50. Langton, S. H., Steenbeek, W. (2017). Residential burglary target selection: An analysis at the property-level using google street view. Applied Geography, 86(3), 145–153. DOI 10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.06.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Nee, C. (2015). Understanding expertise in burglars: From pre-conscious scanning to action and beyond. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 20, 53–61. DOI 10.1016/j.avb.2014.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Abraham, M. (2007). Motivation and personality (translated by Xu Jinsheng et al.). Beijing, China: China Renmin University Press. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools