Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Relationship between Moral Elevation and Prosocial Behavior among College Students: The Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support and Moderating Role of Moral Identity

School of Educational Science, Anhui Normal University, Wuhu, 241000, China

* Corresponding Author: Shuanghu Fang. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(3), 343-356. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.027442

Received 30 October 2022; Accepted 28 November 2022; Issue published 21 February 2023

Abstract

Objectives: The present study examined the relationship between college student’s moral elevation and prosocial behavior. As well as the mediating role of perceived social support and the moderating role of moral identity. Methods: A sample of 489 college students was recruited for the study. They were asked to complete a series of questionnaires, including Moral Elevation Scale (MES), Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), Moral Identity Scale (MIS) and Prosocial Tendency Measure (PTM). As part of the data analysis, we used correlation analysis and the method of constructing latent variable structural equation model to explore the mechanism of action among variables. Results: After controlling for gender, discipline, the research found that: (1) Moral elevation positively predicted the prosocial behavior among the college students; (2) Perceived social support mediated the relationship between moral elevation and prosocial behavior; (3) Moral identity moderated the second half of the model (i.e., the link between perceived social support and prosocial behavior). Specifically, the mediating effect of perceived social support was stronger for college students with high-level moral identity compared to those with low-level moral identity. Conclusions: Moral identity significantly moderates the mediating effect of perceived social support, and the mediating model with moderated is established.Keywords

With the rise of positive psychology, prosocial behavior has become one of the interesting topic of research in China and abroad. Prosocial behavior refers to behaviors that benefit others, such as helping, sharing, donating, cooperating with others, and comforting others, regardless of the situation or expression [1] Research has shown that prosocial behavior benefits not only the recipient of the behavior but also the initiator of the behavior. The implementation of prosocial behaviors can enhance the initiator’s psychological well-being [2], subjective well-being [3], interpersonal relationships [4], attainment of fame and social status [5], and more outstanding personal achievement [6]. Most of the current research focuses on the initiator and recipient roles, while little attention is paid to the bystander role in prosocial behavior. Due to the specificity of prosocial behavior in social life, such as openness and compliance [7], there is a large number of potential spectators, i.e., bystanders, in prosocial behavior situations. Therefore, it may be inadequate to examine only the gainful functions of prosocial behavior on the individual psychological health of the initiator and recipient, and existing studies tend to ignore the effects of prosocial behavior contexts on bystanders and their behaviors. According to social learning theory, bystanders at this point may model prosocial behavior in subsequent social interactions after the initiator of the prosocial behavior [8]. From a social perspective, the prosocial behavior of “bystanders” also plays an important role in maintaining interpersonal relationships and promoting social harmony, but little is known about the mechanisms underlying bystanders’ prosocial behavior. Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to examine the mechanisms underlying the role of bystanders’ prosocial behavior.

1.1 Moral Elevation and Prosocial Behavior

With the current growing public interest in prosocial behavior, moral emotions have been favored by many researchers in the search for influences that enhance the level of prosocial behavior among college students. Researchers believe that moral emotions such as gratitude [9], admiration [10], guilt [11], and shame [12] play an important role. Haidt defines moral elevation as a positive moral emotion that arises when an individual sees the moral behavior of others, appreciates their virtues, and feels his or her moral sentiments are elevated [13]. Zheng et al. and Huang et al. also believed that this moral intention of “Follow the example of a virtuous and wise teacher” can be regarded as one of the typical moral emotions [14,15]. Therefore, moral elevation may play an important role in prosocial behavior as well as other moral emotions.

Empirical studies have shown that moral elevation experienced by bystanders in prosocial behavior situations is as much a moral motivator for moral behavior as any other moral emotion [16], for example, mothers who experience a sense of moral elevation are more likely to soothe and breastfeed their children [17]; prompting whites to overcome racial perceptions and be willing to provide more donations to blacks [18]. Other studies have found that witnessing rare moral behaviors in others can lead people to feel more moral elevation and thus donate more to charity, confirming the relationship between moral elevation and authentic prosocial behavior [19]. Researchers also found that moral elevation not only enhances individuals’ tendency to prosocial behavior, but also causes people to show more authentic volunteer behavior [16]. Therefore, this study proposes hypothesis 1: The moral elevation positively predicts prosocial behavior among college students.

1.2 The Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support

Perceived social support refers to an individual’s expectation or evaluation of social support in facing of stress, and it is the belief that family, friends and other support is available [20]. As an important part of positive psychology, perceived social support is effective in promoting psychological well-being, mainly in terms of its beneficial effects on individuals’ subjective well-being [21,22], life satisfaction [23] and sense of security [24,25]. Previous studies on perceptual social support have focused on perceptual social support for psychological health, but little attention has been paid to the role of perceived social support for prosocial behavior among college students. According to Social Exchange Theory, when individuals perceive more social support, they also provide more support to others [26]. Empirical studies have also shown that high levels of perceived social support significantly contribute to individuals’ prosocial behavior [27,28]. Thus, perceived social support may be another important influencing factor of prosocial behavior.

The Broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions provides the theoretical basis for this study to examine the influence of moral elevation on prosocial behavior through perceived social support. The theory suggests that positive emotions promote the recovery of individuals’ physical and psychological resources and lead to the construction of lasting personal and social resources [29,30]. Research has shown that positive emotions significantly contribute to individuals’ perceived social support [23], positive emotional experiences can facilitate individuals’ perception of social support from various sources. On the one hand, moral elevation, as a positive emotional experience triggered by hearing or witnessing others’ moral behaviors, gives rise to positive perceptions of others, such as the “psychological reality” that “human nature is good and others will help me”, individuals gain a sense of social support from others when they are in distress. On the other hand, as a bystander of moral behavior, this emotional experience may not only motivate individuals to want to help or be close to the initiator of the behavior, but may also motivate individuals to use the initiator of the behavior as a moral role model to provide support and help to others [13,18]. Thus, a sense of moral elevation may enhance individuals’ perceived social support, which is an important influencing factor of prosocial behavior. Therefore, it is hypothesized that perceived social support may be a mediating factor in the relationship between moral elevation and prosocial behavior. Accordingly, this study proposes hypothesis 2: Perceived social support mediates the relationship between moral elevation and prosocial behavior.

1.3 The Moderating Role of Moral Identity

Although the moral elevation may have important effects on prosocial behavior through indirect pathways, it is undeniable that there may be some individual differences in such effects. Therefore, it is important to examine whether the influence of moral elevation on prosocial behavior through perceived social support is moderated by other factors. This will help to clarify “when moral elevation works” in order to examine more deeply the mechanism of moral elevation on prosocial behavior. Empirical studies have shown that moral identity is an important moderator of moral behavior [16,31,32], which means that the level of individual moral identity affects the magnitude of the effect of moral elevation on prosocial behavior. Therefore, this study will examine whether moral identity plays a moderating role in the direct and indirect relationship between moral elevation and prosocial behavior.

Moral identity, an important source of prosocial behavior, refers to moral self-importance, that is, the degree to which virtue is important to oneself [33]. From the social cognitive perspective, moral identity is a self-concept or self-schema composed of moral traits associated with moral behavior, which is stored in memory as a knowledge structure. This knowledge structure varies from person to person due to individual life learning experiences, so moral identity has been considered a relatively stable individual difference variable [33–35]. A meta-analysis of evidence suggests that individuals’ moral identity significantly and positively predicts their prosocial behavior [36]. A systematic review of related research by Hardy et al. also found that moral identity is a stable predictor of prosocial behavior and that individuals with high levels of moral identity exhibit more prosocial behavior relative to individuals with low levels of moral identity [37,38]. Given that previous studies on the interaction of moral identity with moral enhancement and perceived social support are not in-depth, the present study only hypothesized that moral identity positively moderates the direct effect and the second half of the mediating path of “moral enhancement → perceived social support → prosocial behavior” among college students. Specifically, this direct/indirect relationship is relatively strong for individuals with high moral identity and relatively weak for individuals with low moral identity (hypothesis 3).

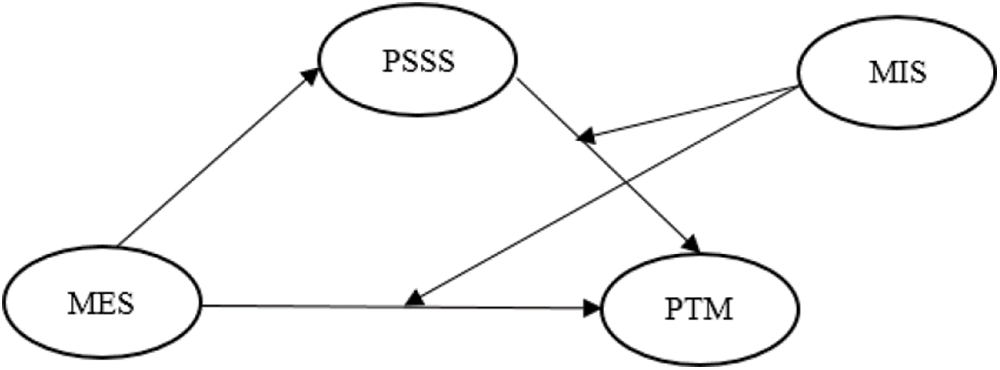

In summary, although the direct relationship between feelings of moral elevation and prosocial behavior has been examined in previous studies, few studies have examined its further mechanisms of action. Based on social exchange theory and positive emotion expansion and construction theory, and by combing and analyzing the existing literature, this study thus constructs a moderated mediating hypothesis model to investigate three main questions: whether bystanders’ moral elevation positively predicts their prosocial behavior; whether perceived social support plays a mediating role between moral elevation and prosocial behavior; and whether moral identity has a positive moderating effect on this mediation model. The model deepens the direct relationship between moral elevation and prosocial behavior, and can answer not only “how” moral elevation influences prosocial behavior, but also “when” this influence is stronger or weaker, in order to explain the mechanism of bystanders’ prosocial behavior. In this way, we can provide reasonable and effective suggestions for enhancing the moral elevation and cultivating prosocial behaviors among college students (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: A moderated mediation model (MES, Moral Elevation Scale; PSSS, Perceived Social Support Scale; PTM, Prosocial Tendency Measure; MIS, Moral Identity Scale)

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Anhui Normal University. All students voluntarily participated in the research and none of them had significant clinical psychological symptoms. All participants were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its latest amendments and were given written informed consent before participating in the study.

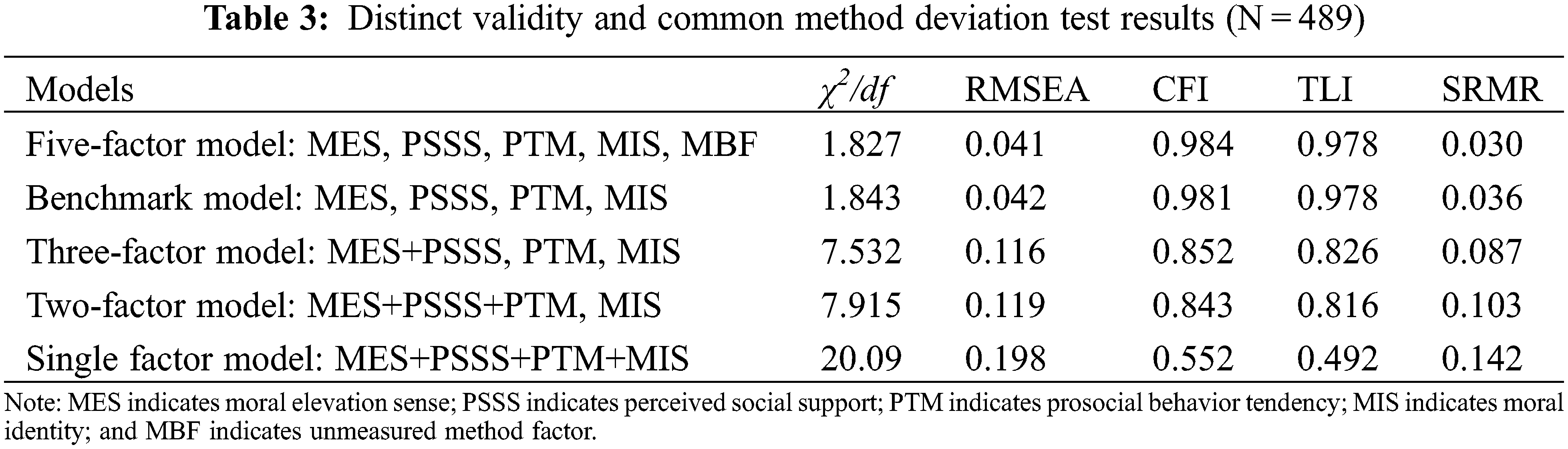

Data were collected using the convenient sampling method, participants were recruited online to complete the questionnaire (Sojump-wenjuanxing) from two full-time colleges and universities in Anhui Province in June 2020. And the questionnaire link was forwarded to class counselors, who then forwarded it to students (non-psychology majors) to fill out. After submitting the questionnaire, participants received a certain reimbursement. In order to prevent subjects from answering regularly, sieve-order questions were randomly set in each part of the questionnaire to eliminate those that did not select the specified option (e.g., “Please select strongly disagree for this question”). After eliminating invalid questionnaires, 489 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective rate of 93.14% with the average age being 20.71 years old (SD = 1.53) (see Table 1).

2.2.1 Prosocial Tendency Measure

The Chinese version of the Prosocial Tendency Measure [7,39] was used in this study. The scale consists of 26 items, which are composed of 6 dimensions: openness, anonymity, altruism, compliance, emotion, and urgency, and using a 5-point Likert scale from 1–5, ranging from “very unlike me” to “very much like me”. “The higher the score, the higher the level of prosocial tendency of the individual”. The scale presents good psychometric qualities among Chinese university students [40]. In this study, the results of the validation factor analysis showed good fit indices: χ2 = 460.87, df = 284, RMSEA = 0.036, CFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.032, and the internal consistency coefficient of the total questionnaire was 0.94.

This study used the Moral Elevation Scale developed by Ding et al. [41], the total scale has 21 items divided into 4 dimensions: emotions and their flow, perceptions of self, perceptions of others and behavioral tendencies, and scored on a scale of 1 to 5 points (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree). The scale has good applicability in measuring college students’ moral elevation [16]. In this study, the results of the validation factor analysis showed good fit indices: χ2 = 388.01, df = 183, RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.945, SRMR = 0.036, and the Alpha coefficient of the total scale was 0.94.

2.2.3 Perceived Social Support Scale

The Perceived Social Support Scale was developed by Dahlem et al. to measure individuals’ perceptions of support from others [42]. The questionnaire was later Chine seized by Yan et al. [43] and consists of three dimensions: family support, friend support, and other support, each with four items, and is scored on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree); higher scores indicate higher Perceived Social Support. In this study, the results of the validation factor analysis showed good fit indices: χ2 = 139.68, df = 51, RMSEA = 0.060, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.966, SRMR = 0.029, and the Alpha coefficient of the total scale was 0.93.

The Chinese version of the Moral Identity Scale was adapted by researcher Chi et al. [44] on the basis of the Moral Identity Scale developed by Aquino et al. [33]. The scale consists of two parts, the first part consists of representative moral traits such as sincere, polite, kind, helpful, upright, loyal and so on; the second part consists of 10 test questions with 2 dimensions, one dimension is the internalized dimension referring to the importance of the above positive moral traits to the self, such as “I aspire to be a person with the above traits”. The other dimension, externalization, refers to the extent to which the individual desires to show that he or she possesses the above positive moral traits in some way, e.g., “My activities in my free time show that I have the above traits”. The researcher found that only the internalization dimension of moral identity is a true predictor of prosocial behavior [33]. Therefore, this study used only the five questions of the internalization dimension of moral identity and asked individuals to rate them on a 7-point scale, 1–7 (completely disagree-completely agree), the higher the score, the higher the level of internalization of moral identity. In this study, the results of the validation factor analysis showed a good fit index: χ2 = 20.66, df = 5, RMSEA = 0.080, CFI = 0.980, TLI = 0.960, SRMR = 0.028, and the Alpha coefficient of this scale was 0.83.

This study mainly used SPSS 22.0 to collate and analyze data, and the confirmatory factor analysis and path analysis were carried out for each questionnaire with AMOS 23.0. First, SPSS 22.0 was used for correlation analysis of variables. Then use Harman separately Single factor test and confirmatory factor analysis were used to test the common method deviation. We also use AMOS 23.0 to construct a latent variable structural equation model to analyze the partial mediation effect of perceived social support and the moderating effect of moral identity on this mediation effect.

The following parameters were used to identify the model fit: χ2, CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), and SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual). The values of CFI and TLI >0.90 were judged to a good fit and the values >0.80 were judged to an acceptable fit [45] (McDonald, Ho, 2002). The values of RMSEA and SRMR <0.08 were judged to an acceptable fit and <0.06 were judged to an excellent fit [46].

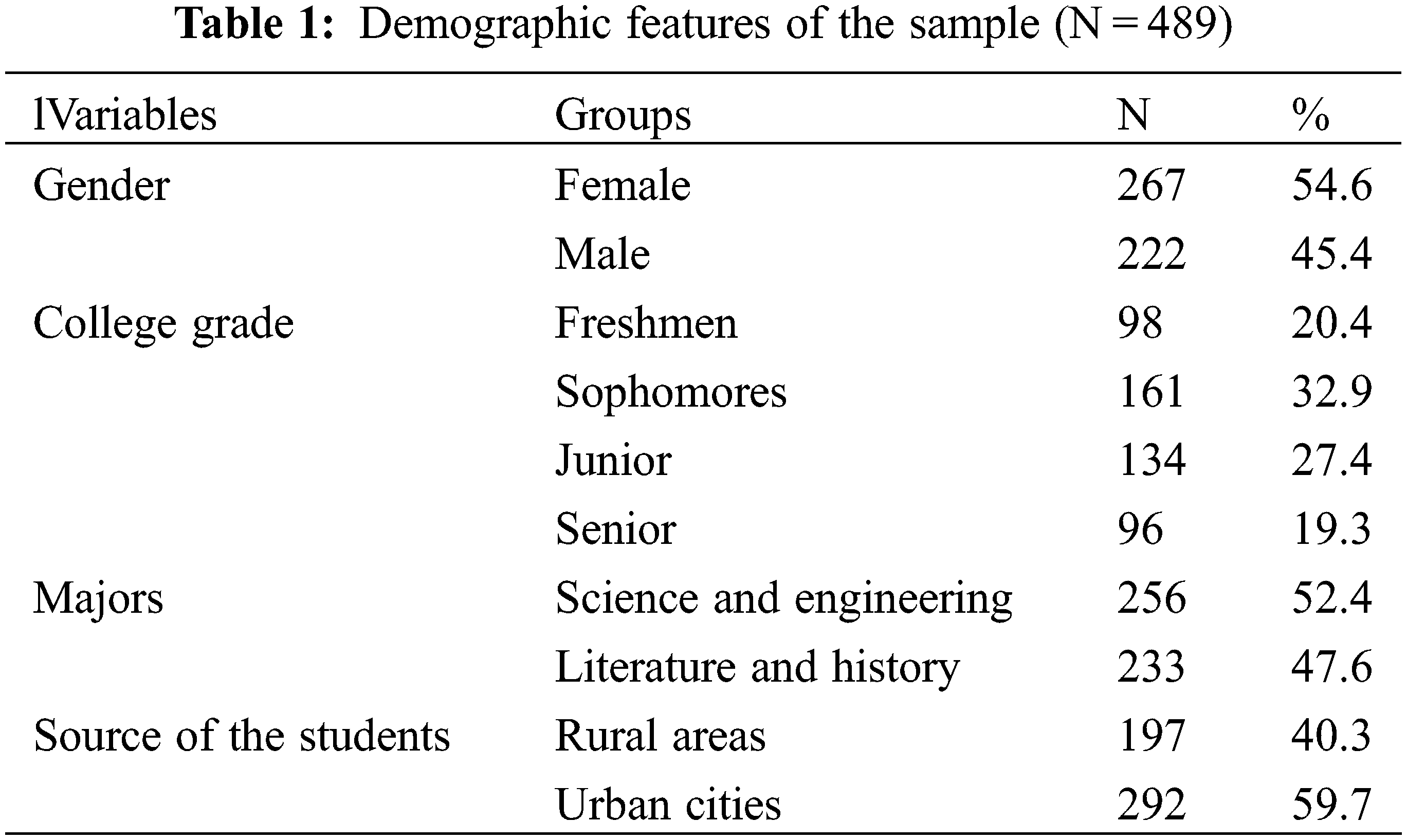

3.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of each variable were performed using SPSS 22.0, and the results are shown in Table 2. Prosocial behavior was significantly negatively correlated with gender, significantly negatively correlated with type of profession, and significantly positively correlated with the moral elevation, significantly positively correlated with perceived social support, and significantly positively correlated with moral identity; moral elevation was significantly positively correlated with perceived social support and significantly positively correlated with moral identity; perceived social support was significantly and positively correlated with moral identity. The demographic variables gender and type of profession were subsequently used as control variables.

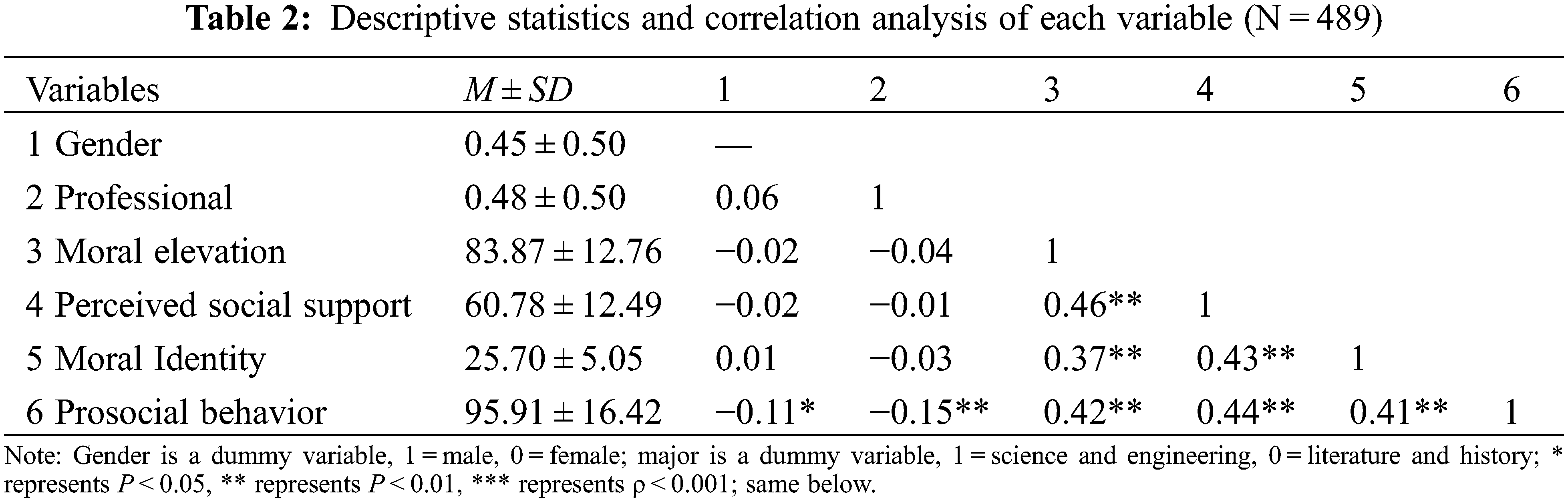

3.2 Discriminant Validity and Common Method Bias Test

In this study, validated factor analysis was used to assess the discriminant validity among variables. Due to the large number of measurement items and small sample size, a question packing strategy was used [47], with dimensional synthetic scores as indicators for each variable: the moral elevation sense questionnaire was divided into 4 dimensions and synthesized into 4 indicators; the comprehension social support questionnaire had 3 dimensions and synthesized into 3 indicators; the prosocial behavior tendency had 6 dimensions and 6 indicators; and the moral identity 5 questions, in order of factor loading size, questions 1 and 5, questions 2 and 3, and question 4 were questions were packaged into 3 indicators. Multi-model validation factor analysis was conducted using AMOS 23.0, and as shown in Table 3, the fit indices of the baseline model (four-factor) were all better than the other competing models, and the fit indices became significantly worse from the three-factor model to the one-factor model. It shows that this research tool can effectively measure the corresponding constructs with good discriminant validity.

The study was procedurally controlled to some extent by anonymous surveys and reverse scoring of some questions. Also, a control unmeasured single method latent factor method was used to test for the presence of common method bias [48]. As shown in Table 3, after adding method factors to the baseline model, the five-factor model fit improved to a limited extent (CFI and TLI improved by less than 0.1, and RMSEA and SRMR decreased by less than 0.05), and the single-factor model fit was extremely poor. Meanwhile, the results of Harman’s one-way test using SPSS 22.0 showed that the amount of variance explained by the common factor with the greatest explanatory power of the data without rotation was 27%, which was lower than the judgment criterion of 40%, and the results indicated that although common method bias might exist, it had a small impact on this study.

3.3 Intermediary Model Test with Moderation

First, referring to the test for moderated mediated effects developed by Wen et al. [49], before the inclusion of mediating variables, the direct predictive effect of moral elevation on prosocial behavior was examined, controlling for the effects of gender and type of profession. The results showed that χ2 = 74.96, df = 53, RMSEA = 0.029, CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.994, SRMR = 0.024, and the overall fit of the model was satisfactory. Moral elevation was positively predictive of prosocial behavior (β = 0.45, ρ < 0.001), and Hypothesis 1 was confirmed.

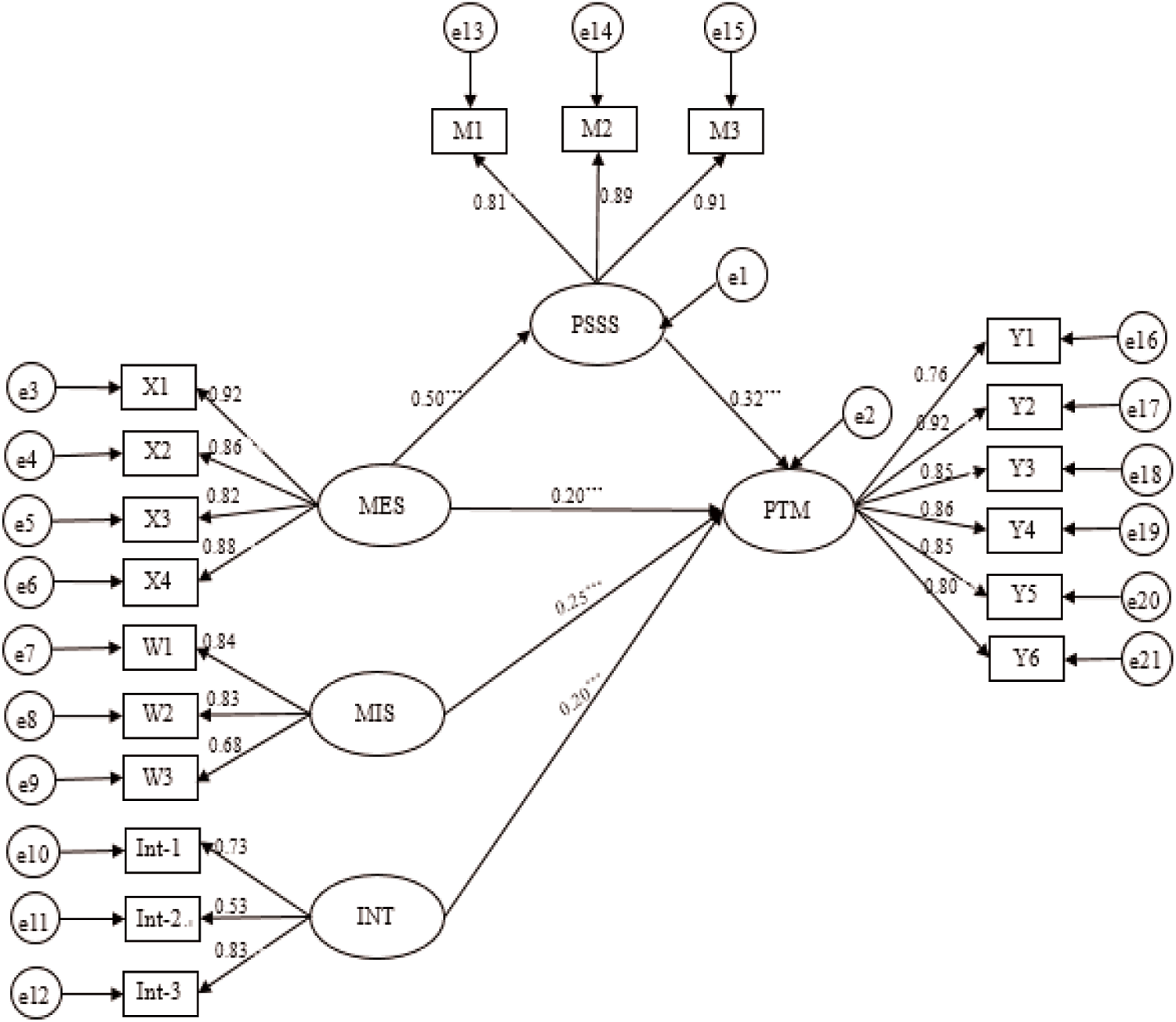

Secondly, the new indicator scores were formed by packing the variables into topics using the paired product method recommended by Wu et al. [50], and the interaction terms were constructed by multiplying the variables in order according to the principle of “large matching with large, small matching with small”. After adding mediating variables, moderating variables and interaction terms, the model χ2 = 652.68, df = 240, RMSEA = 0.059, CFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.928, SRMR = 0.060 fitted well. The results are shown in Fig. 2, with moral elevation positively predicting prosocial behavior (β = 0.20, ρ < 0.001), moral elevation positively predicting perceived social support (β = 0.50, ρ < 0.001), and perceived social support positively predicting prosocial behavior (β = 0.32, ρ < 0.001). Bootstrap tests for the mediating effect of perceived social support indicated that the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval did not include 0 (Partial indirect effect 0.16, Ratio of intermediary effect to total effect is 0.44, SE = 0.01%, 95% CI [0.105, 0.162], ρ < 0.001), indicating that the mediating effect was valid and hypothesis 2 was confirmed.

Figure 2: The influence of moral elevation on prosocial behavior--mediation of perceived social support and moderation of the second half of moral identity (Standardized; MES, Moral Elevation Scale; PSSS, Perceived Social Support Scale; PTM, Prosocial Tendency Measure; MIS, Moral Identity Scale; X1∼Y6 were indicators after packaged; INT (interaction term) was perceived social support × moral identity (e.g., Int-1 = W1 × M3); e1∼e21 were the residual error of each observed variable; control variables and insignificant paths are not shown for the sake of brevity)

Finally, the direct effect was tested to see if it was moderated: the interaction term of moral elevation and moral identity did not predict prosocial behavior significantly (β = −0.07, ρ > 0.05). Then, we tested whether the mediating effect was moderated: the interaction term of perceived social support and moral identity predicted prosocial behavior significantly (β = 0.19, ρ < 0.001), indicating that moral identity moderated the second half of the model’s path significantly, and according to the standardized estimation formula of the interaction term proposed by Wu et al. [50], the standardized estimate of the interaction term of perceived social support and moral identity β = 0.20, hypothesis 3 was confirmed.

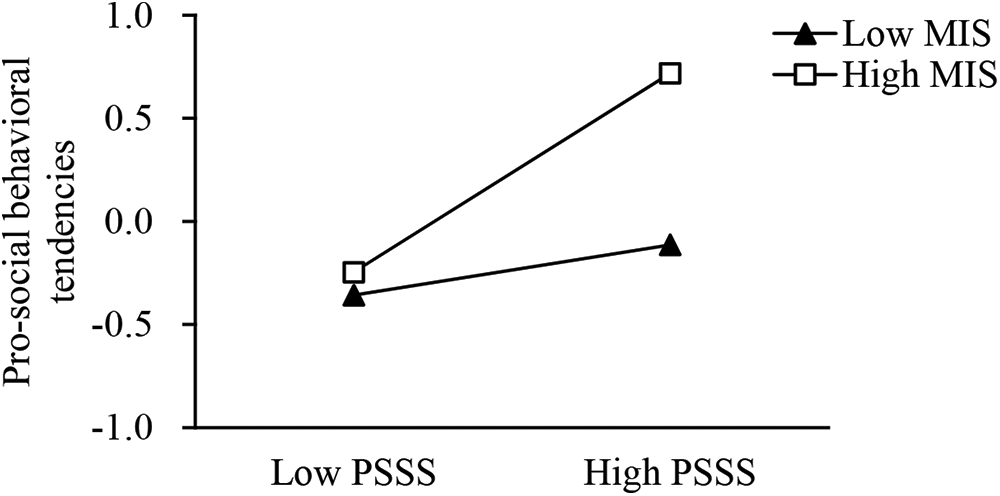

To further reveal the nature of the moderating effect, a simple slope analysis was conducted with the mean moral identity score ±1 standard deviation, divided into a “high moral identity group” and a “low moral identity group” as shown in Fig. 3. The results showed that at high levels of moral identity, perceived social support had a significant positive predictive effect on prosocial behavior (Bsimpleslope = 0.52, ρ < 0.001) with 95% confidence interval [0.347, 0.708], while at low moral identity level, perceived social support was not a significant predictor of prosocial behavior tendency (Bsimpleslope = 0.07, ρ > 0.05) with 95% confidence interval [−0.094, 0.322].

Figure 3: (Standardized) simple slope analysis of moral identity as a moderating effect (MIS, Moral Identity Scale; PSSS, Perceived Social Support Scale)

The current research results showed that: Moral elevation significantly and positively predicted prosocial behavior among college students. Perceived social support mediates between feelings of moral elevation and prosocial behavior, i.e., feelings of moral elevation indirectly influence prosocial behavior through perceived social support. Moral identity level positively moderated the indirect effect of moral elevation perceptions on prosocial behavior through perceived social support. Specifically, this indirect effect was significant for individuals with high moral identity levels, but no longer significant for individuals with low moral identity levels.

4.1 Moral Elevation and Prosocial Behavior of College Students

The findings suggest that feelings of moral elevation significantly and positively predict prosocial behavior among college students, validating hypothesis 1 of this study and consistent with previous research findings [16,51]. This positive emotional experience of following the example of a virtuous and wise teacher after individuals witness their praiseworthy moral behavior motivates individuals to imitate the initiator of the learned behavior and want to engage in more prosocial behavior toward the initiator or unrelated people [13]. Thus, bystander prosocial behavior may be learned by observing the behavior of the initiator of the prosocial behavior, the recipient in a particular setting, and the reinforcement or alternative reinforcement they receive [52]. Once the bystander engages in prosocial behavior at this point, it creates the next meaningful prosocial behavior situation for other “bystanders”, thus building a continuous pattern of positive interactions.

4.2 Perceive the Mediating Role of Social Support

This study found that perceived social support partially mediates the relationship between feelings of moral elevation and prosocial behavior, which verified the hypothesis 2 of this study. This is consistent with previous research findings that positive emotional experiences facilitate perceived social support [23] and that perceived social support plays a positive role in prosocial behavior [27,28]. This study included all three variables in the examination at the same time, revealing that moral elevation is an important factor in enhancing perceived social support and in promoting prosocial behavior among college students. This result also highlights the Positive Emotion Expansion and Construction Theory and Social Exchange Theory perspectives. Positive emotion expansion and construction theory emphasizes that positive emotion experience expands individual psychological and social resources and motivates individuals to actively engage in activities [29,30].

College students are proactive subjects nested in family, community, and sociocultural contexts. After hearing or witnessing the ethical behavior of others in their daily lives, individuals will strengthen their beliefs of receiving support and help from various sources, have a higher sense of security, and thus view and respond to their surroundings with a more positive mindset. Conversely, individuals with lower levels of perceived social support may respond to their surroundings in a negative, apathetic manner. In addition, according to social exchange theory, this “all for one, one for all” reciprocity must conform to the rule that all reciprocal behaviors will reach a fair balance over time; those who do not follow the rules (do not help others) will be punished, and those who do (offer help) will be helped in the future [26]. Thus, in the tradition of reciprocal behavior, the behavior of one party depends on the behavior of the other. In a meaningful prosocial behavior situation, the process begins when at least one person “acts,” and if the bystander responds (offers support to help), a new round of reciprocal behavior begins [16]. Once the process has begun, each outcome creates a cycle of alternative reinforcement [8]. So that individuals who have experienced a positive emotional experience like the moral elevation are motivated to create the next meaningful situation for others by gaining more psychological resources-the perception that they can receive help from others- and thus motivate the individual’s prosocial behavior [27,28].

4.3 The Moderating Role of Moral Identity

This study found that moral identity not only has a direct influence on prosocial behavior, but also positively moderated the second half of the “moral elevation → perceived social support → prosocial behavior” pathway, which confirmed the hypothesis of this study. Specifically, at high levels of moral identity, perceived social support significantly and positively predicted prosocial behavior among college students. At low levels of moral identity, perceived social support was not a significant predictor of prosocial behavior among college students. Possible reasons for this are that high levels of moral identity can promote positive social comparison and attribute behaviors in prosocial behavior situations to positive qualities of individuals, which can enhance the influence of perceived social support on prosocial behavior and motivate individuals to imitate and learn moral behaviors, while individuals with low levels of moral identity tend to attribute behaviors to fulfillment of obligations and situational influences when making social comparisons, rather than spontaneous, voluntary, morally motivated behavior [15]. Therefore, college students with high level of moral identity, they will pay more attention to and maintain the internalized moral norms in their daily lives, and are more willing to imitate the initiators of prosocial behaviors to provide helpful support to others when they experience a sense of moral elevation and appreciate social support; while college students with low level of moral identity, even if they experience a sense of moral elevation to gain a stronger belief of social support, due to ignoring the moral quality importance, they do not necessarily implement prosocial behaviors positively, which ultimately shows that the mediation model is not significant.

This result also provides an empirical basis for the social cognitive model of moral identity, which assumes that moral identity is a self-concept or schema that is stored in memory by a complex knowledge structure. Because knowledge structures are acquired through an individual’s life experiences, the level of moral identity varies from person to person [33–35]. Individuals with high levels of moral identity are more likely to have this moral self-schema activated by prosocial behavior situations and thus more likely to engage in prosocial behavior than those with low levels of moral identity [16,31].

4.4 Research Value and Limitations

This study reveals the mechanisms underlying the effect of a sense of moral elevation on prosocial behavior, which has both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, this study examined the mediating effect of perceived social support and the interaction between perceived social support and moral identity on prosocial behavior on the basis of their direct relationship, which not only helps to understand how a sense of moral elevation acts directly and indirectly on prosocial behavior, but also further reveals the differences in this mediating effect at different levels of moral identity. Thus, this integrated model that examines both mediating and moderating factors on the basis of a direct relationship has higher explanatory strength than the mediating or moderating models alone [53,54]. In addition, this study provides an empirical basis for social exchange theory and positive emotion expansion and construction theory.

In practice, the exploration of the mechanisms of prosocial behavior of college students has implications for the cultivation of prosocial behavior of college students. First, in the process of cultivating prosocial behaviors among college students, educators should consciously cultivate individuals’ sense of moral elevation. Encouraging students to participate in volunteer activities [54], recalling virtuous behaviors in their lives [16] and keeping a diary of moral behavior situations [55] can effectively improve the level of individuals’ sense of moral elevation and thus promote the cultivation of their prosocial behaviors. Second, educators should not only vigorously promote specific moral examples in society to students, but also encourage students to take the initiative to discover moral deeds around them, so as to strengthen individuals’ perception of social support through the inculcation of moral thoughts and moral demonstration over time, and help students perceive that “whenever I am in trouble, I have the support of my family, teachers and friends, or good people in the society”, thus enhancing their level of prosocial behavior. Finally, improving the level of moral identity of individuals is also an important way to promote the development of prosocial behavior. Educators should guide individuals to make reasonable attributions and positively compare prosocial behaviors, and help individuals gradually identify with the importance of the moral traits expressed in prosocial behaviors to themselves, so that they can positively view and emulate prosocial behaviors.

The main shortcomings of this study are the following, which need to be deepened in future studies. First, although the analysis of the relationship between the variables in this study is based on existing theories and studies, the cross-sectional study could not lead to a causal relationship, and longitudinal follow-up studies and experimental studies could be used in the future to reveal the causal relationship between the variables. Second, because all data in this study were collected by self-report method, in which the moral elevation and prosocial tendency questionnaires have high surface validity, subjects’ responses may have social approvability effects leading to bias. Therefore, it is necessary for future studies to collect data using a combination of sources such as individuals, peers, parents, and teachers. Finally, because prosocial behavior is the result of a combination of factors, in addition to perceiving the mediating role of social support between feelings of moral elevation and prosocial behavior and the moderating role of moral identity, other variables such as empathy, interpersonal trust, just world beliefs, and moral inference may also be included. This study was not able to explore the deeper internal mechanisms of this study because it was limited by the initial research idea. Future studies can further investigate the role of different variables at different levels, which will help to truly reveal the mechanism of bystanders’ prosocial behavior and thus better guide practice.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the support of Anhui Provincial Women’s Federation and Anhui Provincial Department of Education 2022 Annual Women’s Theory Research Key Project (2022-FNYJ-002), Open Fund Project of Key Laboratory of Philosophy and Social Science of Anhui Province on Adolescent Mental Health and Crisis Intelligence Intervention, The University Synergy Innovation Program of Anhui Province (GXXT-2022-101), and Anhui Topnotch Talents of Disciplines in Universities and colleges (Shuanghu Fang).

Funding Statement: This project was one of the key projects of the Chinese Ministry of Education and was funded by the Chinese National Office for Education Sciences Planning (Grant No. DBA190311).

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Anhui Normal University. All students voluntarily participated in the research and none had significant clinical psychological symptoms. All participants were treated under the Declaration of Helsinki and its latest amendments and were provided with written informed consent before participating in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial development. In: Eisenberg, N., Damon, W., Lerner, R. M. (Eds.Social, emotional, and personality development, vol. 3, pp. 646–718. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. DOI 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Raposa, E. B., Laws, H. B., Ansell, E. B. (2016). Prosocial behavior mitigates the negative effects of stress in everyday life. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(4), 691–698. DOI 10.1177/2167702615611073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang, J., Zou, H., Hou, K., Tang, Y., Wang, M. et al. (2016). The effect of family function on adolescents’ subjective well-being: The sequential mediation effect of peer attachment and prosocial behavior. Journal of Psychological Science, 39(6), 1406–1412. DOI 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20160619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Carlo, G., White, R., Streit, C. (2017). Longitudinal relations among parenting styles, prosocial behaviors, and academic outcomes in U.S. Mexican adolescents. Child Development, 89(2), 577–592. DOI 10.1111/cdev.12761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hardy, C. L., van Vugt, M. (2006). Nice guys finish first: The competitive altruism hypothesis. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(10), 1402–1413. DOI 10.1177/0146167206291006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang, Y., Li, W., Sheldon, K. M., Kou, Y. (2019). Chinese adolescents with higher social dominance orientation are less prosocial and less happy: A value–environment fit analysis. International Journal of Psychology, 54(3), 325–332. DOI 10.1002/ijop.12474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kou, Y., Hong, H., Tan, C., Li, L. (2007). Revisioning prosocial tendencies measure for adolescent. Psychological Development and Education, 23(1), 112–117. DOI 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2007.01.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Nook, E. C., Ong, D. C., Morelli, S. A. (2016). Prosocial conformity: Prosocial norms generalize across behavior and empathy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(8), 1045–1062. DOI 10.1177/0146167216649932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang, W., Wu, X. (2020). Mediating roles of gratitude, social support and posttraumatic growth in the relation between empathy and prosocial behavior among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 52(3), 307–316. DOI 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2020.00307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xie, J., Zheng, C. (2019). The influence of admiration and group membership on college students’ prosocial behavior. China Journal of Health Psychology, 27(6), 149–153. DOI 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2019.06.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Tang, M., Li, W., Liu, F. (2019). The association between guilt and prosocial behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 27(5), 17–32. DOI 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2019.00773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Fan, W., Ren, M., Xiao, J. (2019). The influence of shame on deceptive behavior: The role of self-control. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(9), 992–1006. DOI 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2019.00992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Haidt, J. (2000). The positive emotion of elevation. Prevention & Treatment, 3(1). DOI 10.1037/1522-3736.3.1.33c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zheng, X., Sun, Z., Miao, F. (2009). The research tendency of moral emotions: From separation to integration. Journal of Psychological Science, 32(6), 1408–1410. DOI 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2009.06.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Huang, X., Liang, H., Li, F. (2018). Moral elevation: A positive moral emotion associated with elevating moral sentiment. Advances in Psychological Science, 26(7), 1253–1263. DOI 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2018.01253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ding, W., Shao, Y., Sun, B. (2018). How can prosocial behavior be motivated? The different roles of moral judgment, moral elevation, and moral identity among the young Chinese. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 814. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Silvers, J. A., Haidt, J. (2008). Moral elevation can induce nursing. Emotion, 8(2), 291–295. DOI 10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Freeman, D., Aquino, K., McFerran, B. (2009). Overcoming beneficiary race as an impediment to charitable donations: Social dominance orientation, the experience of moral elevation, and donation behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(1), 72–84. DOI 10.1177/0146167208325415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Aquino, K., Mcferran, B., Laven, M. (2011). Moral identity and the experience of moral elevation in response to acts of uncommon goodness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(4), 703–718. DOI 10.1037/a0022540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dunkel-Schetter, C., Bennett, T. L. (1990). Differentiating the cognitive and behavioral aspects of social support. In: Sarason, B. R., Sarason, I. G., Pierce, G. R. (Eds.Wiley series on personality processes. Social support: An interactional view, pp. 267–296. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

21. Zeng, X. (2010). Effect mechanism of parenting style on college students subjective well-being. Psychological Development and Education, 26(6), 641–649. DOI 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2010.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yang, Q., Ye, B. (2014). The effect of gratitude on adolescents’ life satisfaction: The mediating role of perceived social support and the moderating role of stressful life events. Journal of Psychological Science, 37(3), 610–616. DOI 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2014.03.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Niu, G., Bao, N., Zhou, Z., Fan, C., Kong, F. et al. (2015). The impact of self-presentation in online social network sites on life satisfaction: The effect of positive affect and social support. Psychological Development and Education, 31(5), 563–570. DOI 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.05.07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li, Y., Wang, Y. (2008). Correlations of perception social support, security and suicide attitude. Chinese Journal of School Heath, 29(2), 141–143. DOI 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2022.09.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Han, J., Leng, X., Gu, X. (2021). The role of neuroticism and subjective social status in the relationship between perceived social support and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Difference, 168. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Cropanzano, R. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. DOI 10.1177/0149206305279602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Guo, Y. (2017). The influence of social support on the prosocial behavior of college students: The mediating effect based on interpersonal trust. English Language Teaching, 10(12), 158–163. DOI 10.5539/elt.v10n12p158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li, W., Guo, F., Chen, Z. (2019). The effect of social support on adolescent prosocial behavior: A serial mediation model. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(4), 817–821. DOI 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.04.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300–319. DOI 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1377. DOI 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198567523.003.0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yang, J., Wang, X., Gao, L. (2015). Moral disengagement and college students’ deviant behavior online: The moderating effect of moral identity. Psychological Development and Education, 31(3), 311–318. DOI 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.03.08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ding, F., Na, W. (2015). Effect of empathy on college student’s charitable donation in real acute disease situation: Moderated mediating effect. Psychological Development and Education, 31(6), 694–702. DOI 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.06.08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Aquino, K., Reed, A. II. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Shao, R., Aquino, K., Freeman, D. (2008). Beyond moral reasoning: A review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(4), 513–540. DOI 10.5840/beq200818436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed, A. (2009). Testing a social cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 123–141. DOI 10.1037/a0015406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hertz, S. G., Krettenauer, T. (2016). Does moral identity effectively predict moral behavior? A meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 20(2), 129–140. DOI 10.1037/gpr0000062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hardy, S. A., Carlo, G. (2005). Identity as a source of moral motivation. Human Developmen, 48(4), 232–256. DOI 10.1159/000086859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Hardy, S. A., Carlo, G. (2011). Moral identity: What is it, how does it develop, and is it linked to moral action? Child Development Perspectives, 5(3), 212–218. DOI 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00189.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Carlo, G., Randall, B. A. (2002). The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 31(1), 31–44. DOI 10.1023/A:1014033032440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Hong, H., Kou, Y. (2008). The further study on the correlations of prosocial tendencies and prosocial moral reasoning with canonical correlation analysis. Psychological Development and Education, 24(2), 113–118. DOI 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2008.02.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ding, W., Wang, X., Sun, B. (2014). The structure and measurement of the moral elevation. Advances in Psychology, 4(6), 777–787. DOI 10.12677/ap.2014.46102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, G. D., Walker, R. R. (1991). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: A confirmation study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47(6), 756–761. DOI 10.1002/1097-4679(199111)47:6<756::aid-jclp2270470605>3.0.co;2-l. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Yan, B., Zheng, X. (2006). Researches into relations among social-support, self-esteem and subjective well-being of college students. Psychological Development and Education, 22(3), 60–64. DOI 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2006.03.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Chi, Y. (2005). The influence of personality and situational priming on prosocial behavior (Doctoral Dissertation). East China Normal University, China. DOI 10.7666/d.y904531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. McDonald, R. P., Ho, M. H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64–82. DOI 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(3), 320–341. DOI 10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wu, Y., Wen, Z. (2010). Item parceling strategies in structural equation modeling. Advances in Psychological Science, 19(12), 1859–1867. DOI 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2011.01859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wen, Z., Huang, B., Tang, D. (2018). Preliminary work for modeling questionnaire data. Journal of Psychological Science, 41(1), 204–210. DOI 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20180130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Wen, Z., Ye, B. (2014). Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: Competitors or backups? Acta Psychologica Sinica, 46(5), 714–726. DOI 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.00714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wu, Y., Wen, Z., Hou, J., Herbert, W. M. (2011). Appropriate standardized estimates of latent interaction models without the mean structure. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 43(10), 1219–1228. DOI 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2011.01219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Pohling, R., Diessner, R., Stacy, S. (2019). Moral elevation and economic games: The moderating role of personality. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1381–1381. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Bandura, A. (1978). Social learning theory of aggression. Journal of Communication, 28(3). DOI 10.1111/j.1460-2466,1978.tb01621.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Yu, S., Liu, Q. (2019). The relationship between body dissatisfaction and suicidal ideation of adolescents: A moderated mediating model. Psychological Development and Education, 35(4), 486–494. DOI 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2019.04.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Bao, Z., Zhang, W., Li, W. (2013). School climate and academic achievement among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Psychological Development and Education, 29(1), 61–70. DOI 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2013.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Cox, K. S. (2010). Elevation predicts domain-specific volunteerism 3 months later. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(5), 333–341. DOI 10.1080/17439760.2010.507468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools