Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Comparison of Self-Strength, Seeking Help and Happiness between Pakistani and Chinese Adolescents: A Positive Psychology Inquiry

1 Department of Education, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, 510006, China

2 Department of Education, The University of Lahore, Lahore, 54950, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Xing Qiang. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(3), 389-402. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.024130

Received 22 June 2022; Accepted 15 August 2022; Issue published 21 February 2023

Abstract

Adolescents’ emotions and preferences are influenced by their childhood experiences. In today’s world, there is a pervasive eagerness for happiness. Happiness has been linked to feelings of self-strength, seeking help, and psychological health. The current quantitative research was designed with a positive psychological perspective to compare Pakistani and Chines adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness. The research design of the study was causal-comparative. The study population consisted of 400 Pakistani and 409 Chinese adolescents studying in the elementary grades of both countries. The sample was selected by using a simple random sampling technique. It consisted of 413 boys (51%) and 396 girls (49%), 319 (39) of them were from the age group of 13–14 years, 386 (48%) of them were from the age group of 15–16 years, and 104 (12.9%) were from the age group of 17–18 years. Three different scales were developed to collect study data. Independent sample t-test and simple linear regression were used to test study hypotheses. The analysis revealed that Pakistani adolescents have significantly higher self-strength, seeking help and happiness than their counterparts. It was also found that adolescents’ self-strength and seeking help significant affect their happiness. Based on the findings, it was suggested to investigate the factors contributing to the improved self-strength, seeking help, and happiness of Pakistani adolescents. It was also recommended to investigate the mediating effect of adolescents’ self-strength on the relationship between their happiness and seeking help.Keywords

Positive health effects, such as creating a solid self-concept entwined with consciousness and increasing pro-social activities, are possible because of the social setting [1]. A healthy self-concept and improved pro-social behavior can be achieved by providing an excellent social atmosphere for youngsters to grow up [2]. It also emphasizes that healthy bodies and strong social ties are essential for identifying one’s strengths and flaws [3]. According to Azizah et al. [4], a positive self is critical for people to survive and prosper. The strength of a person’s relations with their social influences is thought to play a role in their feelings.

The ability to focus and respond to multiple tasks at once and possess a sense of self-adequacy and vigor, as well as regulate one’s impulses, is considered a sign of strength [5]. The structure and viewpoint provided by positive traits can assist people, teams, and organizations in functioning and flourishing [6]. It is evident from the literature that Suroso et al. [7] arranged activities that create courage in the face of various situations as a sign of self-strength. At the same time, self-strength concerns how people deal with life’s challenges and obstacles [8]. Literature reveals that self-strengthening, pursuing happiness with consciousness development, and vastly improving adolescents’ personalities can help them live a balanced and friendly life [9].

Happiness is a state of mind that comes from a firm belief in oneself. It has also been found that happier people have more excellent interpersonal skills, empathy for others, a good outlook on life, and a strong sense of self-worth and fulfillment [10]. Adolescence necessitates a sense of well-being. Unhappy adolescents have more behavioral and emotional issues than joyful adolescents [11]. Asking someone how they think regarding their fulfillment, enjoyment, and enthusiasm might yield information about happiness’s physiological and behavioral components [12]. Content people have faith in their abilities. A good sense of well-being, strong social skills, understanding, and a positive attitude toward life are signs of someone content with their life, relaxed, and high self-esteem [12].

Ford et al. [13] argued that people’s feelings and desires are shaped by their cultural upbringing. The desire for happiness is widespread in modern nations. Happiness is positively linked to well-being and mental health, but current research reveals that a strong desire to feel happy, or a high value placed on happiness, is detrimental to one’s well-being. Happiness is defined as having the most positive impact over the negative impact, emphasizing the aesthetic judgment of one’s current condition. Despite its all-encompassing character, happiness is a topic that has received little attention in nursing research. Since happiness affects all aspects of life, health-related studies will continue to be fruitful in this field [14].

Studies have shown helpful-seeking behavior to be an effective strategy for engaging students on multiple levels: intellectually, behaviorally, and psychologically. Adaptability and the ability to overcome hurdles in the classroom may be linked to students’ willingness to ask for help [15]. According to Hendriks et al. [16], enhancing personal qualities such as cognitive empathy and friendliness may even reduce the stigma associated with people seeking care for psychological issues. In addition, seeking help can help adolescents develop critical social skills that help them stay focused in school. As a result, as part of a transactional process, it is crucial to examine how seeking help impacts expectancy-value attitudes over time [17]. Understanding the psychological mechanisms that foster help-seeking behavior is vital since adolescents frequently postpone seeking aid and advice when needed [18]. It is critical to understand what attitudes motivate adolescent help-seeking behavior and how help-seeking can enhance achievement motivation [19].

Research has shown psychological characteristics to predict future help-seeking behavior. According to their findings, educational performance has distinct personal contributions, and interpersonal showcase aims to determine help-seeking behavior [20]. In schools and other studying situations, being able to draw on the support of others when facing problems is an effective method. Because they miss out on valuable social interactions with their instructor and classmates that might help them learn and succeed, learners who need assistance but do not ask for it will struggle in their grades. It is also found that educational consciousness influences people’s willingness to seek help [21].

A lack of definitive positive psychology therapies can decrease psychological symptoms and promote well-being in students, considering their possible contribution to preventive research [22]. People who study the causes and effects of extreme sadness have traditionally supported psychological research. This trend continues today. Despite increased investigations on happy people over the past years, there is still a shortage of studies focusing explicitly on the potential advantages of being extremely happy [23]. To the researcher’s best knowledge, no study has been yet conducted to explore the impact of self-strength on adolescent happiness in positive psychology with the mediating role of seeking help. Keeping in view the emerging relationships between the Pakistan and China governments and the exchange of students’ delegations to understand cultural differences in more depth, the researcher conducted this study and compared the perceptions of Chinese and Pakistani adolescents on said phenomenon.

The following research objectives guide this paper:

1. To compare Pakistani and Chinese adolescents across self-strengths, seeking help attitude, and happiness.

2. To investigate the effect of adolescents’ self-strength on their happiness.

3. To determine the effect of adolescents’ seeking help on their happiness.

This paper section presents an extensive literature review of the study variables. Relevant literature was searched from the research databases like Google Scholar, ERIC, Springer, and different educational psychology journals. Summaries of relevant data have been given below under appropriate headings. The current study’s findings are compared and contrasted with those of these studies under the discussion heading.

Shoshani et al. [22] evaluated a positive psychology classroom program to improve psychological health and strengthen the total academic teachers and learners at an elementary school. It was determined that the experimental group, but not a long waiting list-controlled group, encouraged improvements in mental conditions and stress and specific well-being indicators, using a 2-year longitudinal repeated measures design. People in the treatment group witnessed profound declines in overall discomfort, nervousness, and depressed mood, while those in the control group saw a substantial increase in ailments. Aside from these positive effects, the treatment lowered signs of empathic concern and increased participants’ feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy. Norrish et al. [24] addressed academics and psychological development, and educational practitioners engaged in the scientific data supporting the use of positive psychology therapies with teenagers. The positive psychology topics examined include the true happiness theory, optimism, mentoring, appreciation, compassion, and abilities therapies. Though positive psychology is still developing, and more study in teenage communities is required, evidence for psychosocial interventions in promoting teenagers’ psychological health is growing.

Deep aquifers of innovation and well-being can be tapped into when one has a particular strength of character. Although it is now dormant, you possess an inherent vital energy and enthusiasm source [25]. Self-strength and self-confidence are essential for dealing with psychological and social issues of all sizes. At the heart of it all is the ability to regulate one’s feelings and natural drives in a self-confident and adaptable way. It can be hard to execute these abilities in household, career, and performance contexts [26].

Maintaining integrity can be challenging, while interacting with people more healthily can be difficult. A family’s ability to maintain a self-image can ironically be the secret to improving the home. An autonomous and interdependent environment fosters a sense of self-determination and self-confidence, leading to greater productivity and success. People in a relationship can recognize and help each other progress through different phases of self-development, which can lead to better cooperation and well-being [27].

An online self-reporting questionnaire gathered direct personal experiences of male sexual help-seeking conduct. An analysis of relevant literature on men’s refusal to acknowledge help overall, particularly for counseling, is presented. Social and personal constraints influence men’s readiness to seek help for mental health difficulties [28]. Likert and open-ended statements were included in the questionnaire developed. The answers of male participants have shown adherence to male standards. Male counselees’ attitudes about therapy are examined, and new directions for study are proposed.

However, unintended data shows that people with greater optimism may have a significantly larger willingness to seek support than individuals with lower levels of optimism in the broad sense. The possible connections between hope and assistance intentions should profoundly depend on the specific help-seeking situation [23]. McDermott et al. [23] argued that in addition to being purposeful, regulating cognition or knowledge, looking for assistance can serve as vital support for learners’ commitment and psychological capability, even after eliminating learners’ help-seeking behavior and understanding. Pupils may have been given underlying psychological management structuring through specific help-seeking cues found in research [21].

While studying help-seeking behavior in sixth grade (N = 217), Ryan et al. [20] evaluated the psychological factors and consequences. Learners’ scores were acquired twice a year from academic records. Educators believed in adolescents’ help-seeking attitudes; children stated their academic identity and personal performance aspirations. Achieving adaptable help-seeking was significantly linked to first quarterly scores and students’ happiness. An adapted help-seeking aim was also inversely connected to individual performance. Another study also witnessed that successful students are not only persevering on their own; they are engaged in social interactions with people who help them learn. According to their research, it is also evident from the literature that learners’ instructional behavior is linked to their social aspirations, and social problems consequently influence learners’ school tasks [29].

On the other hand, adolescents are less likely to seek therapy for their problems than adults or adolescents without similar issues [30]. The importance of help-seeking behavior is that it can reduce the persistence and severity of the problems for which help is sought. According to Toren et al. [31], children and adolescents who talked about their concerns with their mothers or friends had a significantly lower rate of behavioral disorders. According to a survey, university students’ top three perceived benefits of obtaining therapy for mental health disorders were reduced stress, increased cognitive functioning, and the settlement of one’s condition [32].

Females ask for assistance, and males attempt suicide. One study showed that 75% of those who started helping in a suicide awareness facility were females, while 75% of all who died by suicide in the same year were males [8]. According to experts, males are reluctant to seek or use professional assistance because they are afraid of being judged. Considering the literature on seeking help, the researcher developed the following hypothesis.

The demographics of adolescents experience very significant happiness levels. Exceptionally happy adolescents exhibited considerably better mean values on all classroom, social, and interpersonal relations factors and statistically lower scores on despair, adverse impact, and societal pressures than adolescents with medium and relatively low happiness levels. For the meager, personal value, compassion, identity, and positive affect were found to have a significantly more significant positive effect on overall life happiness than extreme happiness [33].

Thus, studies on adolescents’ mental health have primarily focused on concerns of psychological functioning [34]. But according to the WHO, mental health is a state of well-being in which the individual realizes their strengths, manages life’s usual struggles, functions effectively and meaningfully, and contributes to their community [35]. As per the best knowledge of the researcher, there was no literature found on these variables, especially compared to Pakistani and Chinese adolescents. That is why the researcher designed the following hypothesis to fill this gap in the literature. The following hypotheses guided the current study based on the above-narrated literature review:

H10: There is no significant difference between Pakistani and Chinese adolescents’ self-strengths, seeking help, and happiness.

H1a: There is a significant difference between Pakistani and Chinese adolescents’ self-strengths, seeking help, and happiness.

H20: There is no effect of adolescents’ self-strength on their happiness.

H2a: There is an effect of adolescents’ self-strength on their happiness.

H30: There is no effect of adolescents’ seeking help on their happiness.

H3a: There is an effect of adolescents’ seeking help on their happiness.

This paper explores self-strength, happiness, and seeking help among Pakistani and Chines adolescents. The positivistic school of thought guided the research. A descriptive design was adopted to investigate the phenomenon under study.

Because this study aims to compare adolescents’ self-strengths, seeking-help attitudes, and happiness in China and Pakistan, the study’s population comprises all adolescent pupils in both countries. Adolescence is the period between 12 and 18 and is the sixth stage in a child’s development [36]. A sample is a subset of a population, and the sample was chosen from the population using a random sampling procedure. Two distinct samples were selected. The first sample was from Pakistani high schools, while the second was from Chinese schools. Students between 12- and 18-year old studying in Pakistani and Chinese high schools were randomly chosen. The minimum sample size for a descriptive study should be a minimum of 100 [37]. As a result, 809 students were selected as a sample for the data-gathering procedure: 400 Pakistani adolescents and 409 Chinese adolescents.

For data collection, the researcher developed three different questionnaires having demographic parts. There are three variables in this study: self-strength, seeking help, and happiness, and they were all intended to be studied in the context of positive psychology. Therefore, the researcher developed three scales on the five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to agree strongly) for data collection. The first scale was developed to measure adolescents’ self-strength, and items like, I am helpful to the ill persons, and I consolidated others when they got hurt are included in this scale. The second scale was developed to measure their seeking help on items like asking for help from my teachers in learning and asking for help in balancing my emotions. The third scale was developed to measure their happiness on the items like, I feel pleased with my capabilities, and I feel that life is rewarding. Adolescents were first asked to complete the Self-Strength Scale for Adolescents (SSS-A). Seeking Help Scale for Adolescents (SHS-A) was developed to measure adolescents seeking help. In addition, another scale called the Happiness Scale for Adolescents (HS-A) was developed to measure adolescents’ happiness. These scales were developed on a three-point Likert scale with options 1 (not at all for me), 2 (somewhat true to me), and 3 (true to me).

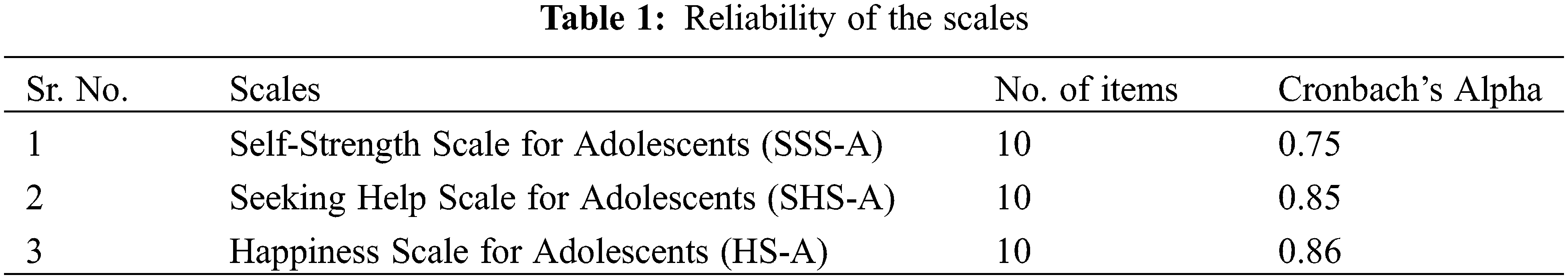

The questionnaires were validated through expert opinion and pilot testing. Five positive psychology experts were requested to give expert opinions, and scale items were modified in light of feedback given by the experts. Then these questionnaires were piloted and tested, and again, the problematic items were revised to match the students’ level. The scales’ reliability was also ensured, and Cronbach’s Alpha was used to measure the internal consistency of the items in all three scales of Table 1.

For this paper, data was collected in the post-COVID situation when schools were reopened in Pakistan. After taking informed consent from the school heads, the researcher collected data personally by visiting the classrooms. Students were informed of the purpose and value of their contribution to this study. All the questionnaires were distributed personally to Pakistani adolescents. After a week, they were given a gentle reminder for the completion by phone calls to their respective school teachers. From Pakistani students, data was collected in August 2021. While from the Chinses adolescents’ data was collected using the question star site in September 2021.

While collecting data, the researcher ensured the ethical considerations for the research. Informed consent was taken from the school heads before data collection. After meeting the students, the researcher shared the paper objectives with them and assured them that the data collected would be used only for this research and not for any other purpose. They were assured of their confidentiality and anonymity. Considering the potential threats, they were also allowed to withdraw from the study settings at any research stage.

After collecting the adolescent questionnaires, the researcher recorded data in a Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) file. The data were screened out, and after identifying missing values, they were managed by the mean values. For data analysis, the researcher used the software SPSS version 26. Socio-demographic information was analyzed using the frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation, and the results are given below. Furthermore, after data screening, study hypotheses are tested for inferential statistical analysis using the independent sample t-test and simple linear regression at an Alpha level of .001.

The results of the socio-demographic information and the instrument scales are below under relevant sections according to the study objectives and hypotheses.

4.1 Locality, Gender, and Age Analysis of the Adolescents

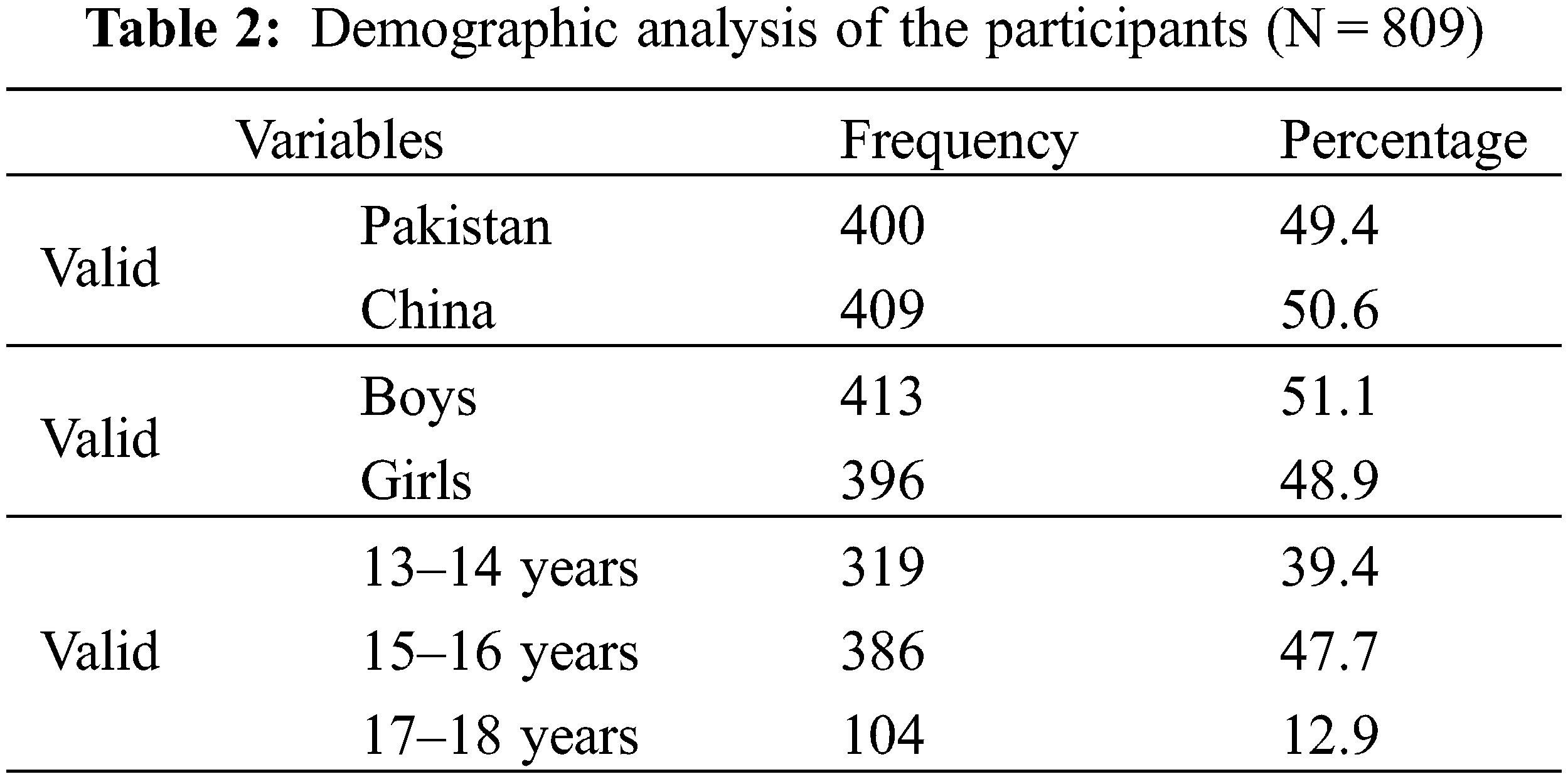

Overall, 809 adolescents from both countries took part in the study. A demographic analysis is given below (Table 2).

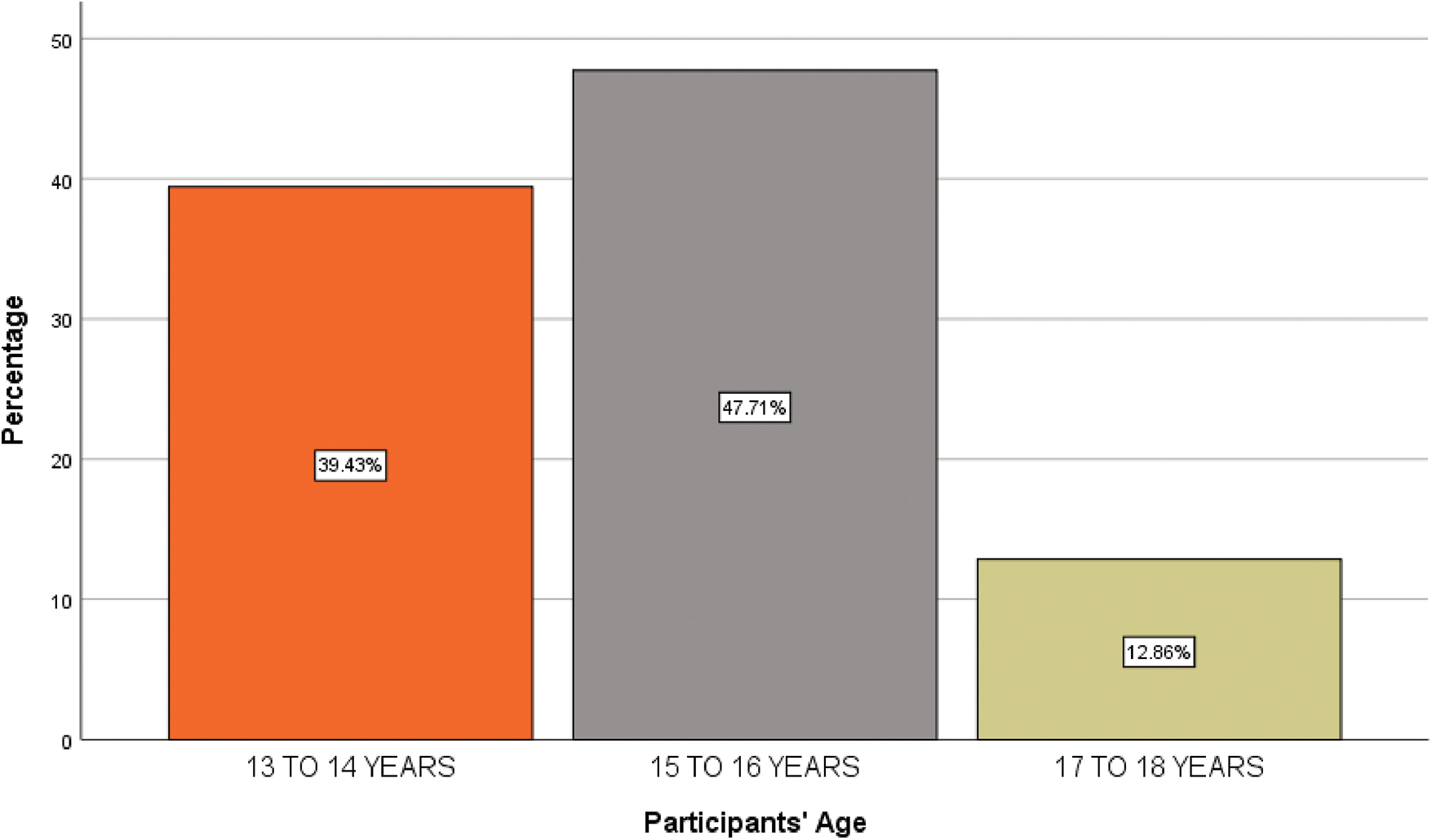

The above table shows that 809 respondents participated in the current study, among which there are 400 Pakistani and 409 Chinese Adolescents, 413 girls, and 396 boys. Besides, almost half (47%) of respondents were 386 aged 13 to 14 years, followed by 319 (39.4%) in the age group of 15–16 years and 104 (12.9%) from the age group 17–18 years. Demographic information is also shown in the form of graphs in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Country-wise detail of adolescents

The above graph shows that the overall number of Chinese adolescents (50.56%) is higher than that of Pakistani adolescents (49.44%).

The Fig. 2 bar chart shows that the number of girls (51.05%) was higher than their counterparts (48.95%).

Figure 2: Gender-wise detail of adolescents

The Fig. 3 bar chart expresses that most adolescents (47.71%) belong to the age group of 15 to 16 years, followed by the adolescents (39.43%) of the age group 13 to 14 years. At the same time, only 13% of the respondents are 17 to 18 years old.

Figure 3: Age-wise detail of adolescents

4.2 Difference between Pakistani and Chinese Adolescents in Self-Strengths, Seeking Help, and Happiness

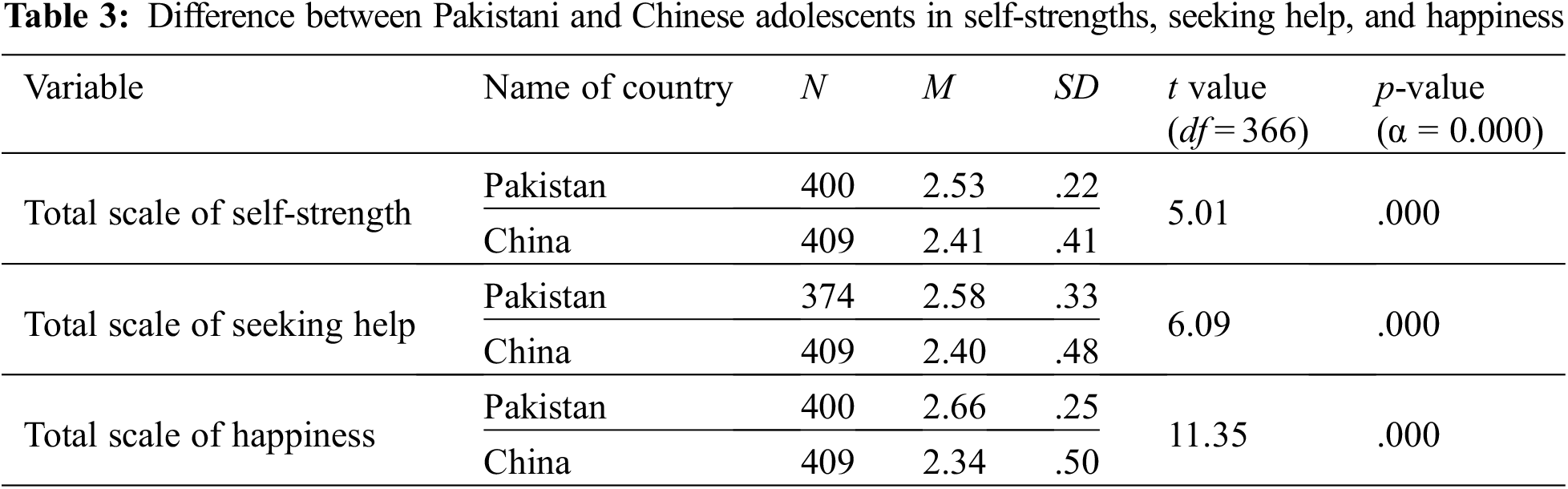

The study’s first hypothesis was tested using the independent sample t-test to see the difference between Pakistani and Chines adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness. The results of the independent sample t-test are presented in Table 3.

From the above table, it is clear that Pakistani adolescents’ self-strength (M = 2.53, SD = .22) is higher than that of the Chinese’ adolescents (M = 2.41, SD = .41) and is statistically different at t (807) = 5.01, p = .000 at the Alpha value of .001. From the analysis, it is also clear that Pakistani adolescents’ seeking help (M = 2.58, SD = .33) is higher than that of Chinese adolescents (M = 2.40, SD = SD = .48) and is also statistically significant at t (807) = 6.09, p = .000 at Alpha level of .001. The above table also indicates that Pakistani Adolescents’ happiness (M = 2.66, SD = .25) is higher than that of their counterparts (M = 2.34, SD = .50) and is also statistically significant at t (807) = 11.35, p = .000 at Alpha level of .001. From the analysis, it is clear that Pakistani adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness are significantly higher than Chinese adolescents.

The researcher deployed the simple linear regression to investigate the effect of adolescents’ self-strength and to seek help for their happiness. The second and third hypotheses are tested at the significance level of .001. The results are provided in the following table.

4.3 Effect of Adolescents’ Self-Strength on Their Happiness

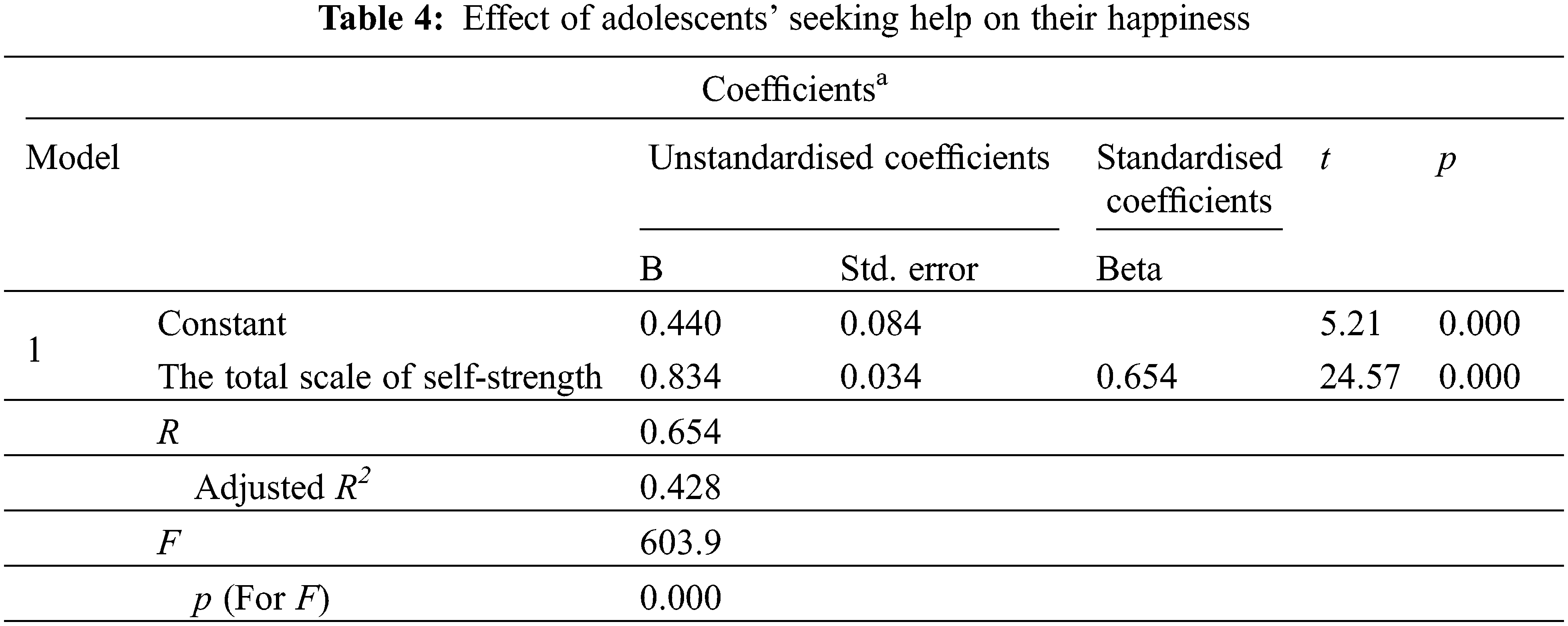

To test the study’s second hypothesis, the researcher deployed simple linear regression to investigate the effect of adolescents’ self-strength on their happiness. The results are given in the following Table 4.

The above table reveals the results for the second hypothesis. The R-value is 0.654, which strongly correlates with adolescents’ self-strength and happiness. The value of R2 is .43, which explains that adolescents’ self-strength can account for a 43% variation in their happiness. The value of the F-Ratio is 603.09, which is statistically significant, p = 0.000 at the Alpha level of 0.001. Adolescents’ self-strength has a statistically significant effect on their happiness. Besides, adolescents’ self-strength is also a good predictor of their happiness.

4.4 Effect of Adolescents’ Seeking Help on Their Happiness

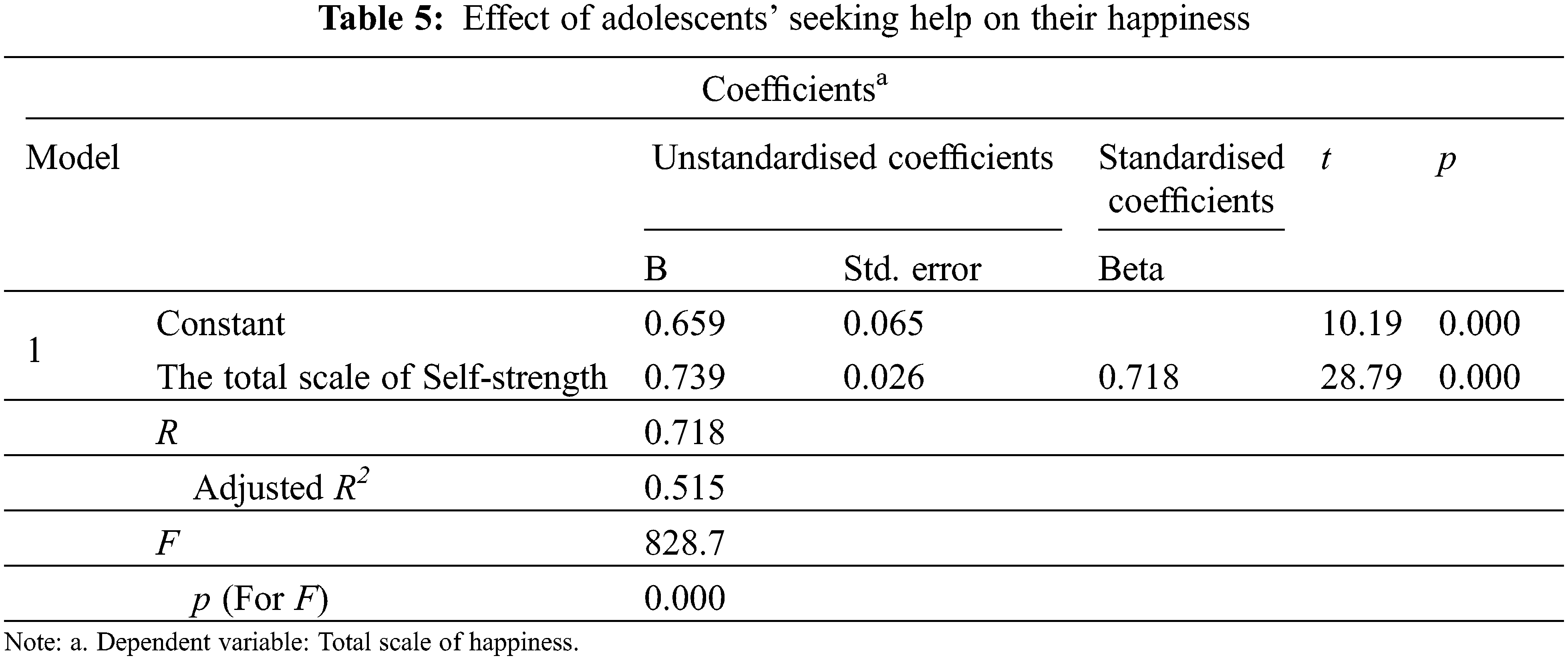

In this part of the paper, data analysis has been performed to test the third hypothesis of the study. The effect of adolescents seeking help has been investigated on their happiness at the significance level of 0.001. Data has been interpreted in the following Table 5.

The above table indicates the results of the third hypothesis of the study. The R-value is 0.718, which strongly correlates with adolescents’ seeking help and happiness. The value of R2 is .52, which explains that adolescents’ self-strength can account for a 52% variation in their happiness. The value of the F-ratio is 828.7, which is statistically significant, p = 0.000 at the Alpha level of 0.001. From the above data analysis, it is clear that adolescents’ seeking help significantly affects their happiness. Having a strong correlation is a good predictor of their happiness.

Positive psychology is very influential in the development of adolescents. It provides them with experience and competencies that will have a long-term, meaningful effect on their lives. There has recently been an upsurge in calls to use personality reinforcement in schools and youth-oriented setups. Even though learning positive thinking constructs for teenagers is appealing, more research into the usefulness of such practices is required [24]. The current quantitative study was designed to see the influence of positive psychology on adolescents’ lives. The study’s significant variables are adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness. Shoshani et al. [22] evaluated an elementary school’s positive psychology classroom program to improve teachers’ and students’ psychological health. As a result of the current research, adolescents’ self-strength significantly impacts their happiness. Self-confidence is also a good predictor of adolescent happiness. Therefore, the study results supported the argument presented by Shoshani et al. [22].

The study’s first research objective and hypothesis were developed to compare Pakistani and Chinese adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness. After deploying the independent sample t-test, the results confirmed the rejection of the null hypothesis. It revealed that Pakistani adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness are better than Chinese adolescents, not only better but significantly different. It is one of the critical findings of the study. There is a need to identify the factors contributing to the happiness of Pakistani adolescents, and they had improved happiness and other study variables than their counterparts. In the literature, no past studies were found comparing Pakistani and Chinese elementary school adolescents. Still, the way Pakistani show higher self-strength, seeking help, and happiness can result from their self-confidence [38] and self-determination [39], which helps them have better self-strength [40]. Pakistani adolescents are physically strong and are more focused; therefore, they have strong self-strength [41]. It is also evident that Pakistani adolescents have higher help-seeking [42] because they are more involved in their religious activities [43]. The current study also supported the findings of Kholifah et al. [44], who revealed that Pakistani students feel more happiness because they tend to be more emphatic.

The current study also revealed that adolescents’ self-strength significantly affects their happiness and rejects the second null hypothesis of the study. Ha [25] mentioned that when one possesses a particular strength and courage, one can tap into unconfined aquifers of transformation and well-being that can be accessed. Although it is currently dormant, you have a natural source of vital energy and enthusiasm. His argument continues by stating that self-strength and happiness are intimately linked. The current study also supports the argument of Ha [25] by revealing that adolescents’ self-strength and happiness are strongly correlated. With an R-value of 0.654, adolescents’ self-strength and happiness are strongly linked. This means that adolescents’ self-strength accounts for 43% of the variation in their happiness. Suppose adolescents’ self-strength increases one unit, and their happiness will increase by 0.43. Also, according to Zhang [9], our research found that self-strength and social worlds form a dialogue that strengthens each other. These people still had confidence in the psychological task, believing that it could help them improve their well-being. The current study also supported the study findings of Kholifah et al. [44], who argued when adolescents meet new friends, they become much happier, and their happiness is derived from their self-strength.

The current study also revealed that adolescents’ seeking help significantly affects their happiness and rejects the third null hypothesis of the study. In a study conducted by Shin et al. [38], it was found that happiness and prior seeking help behavior are associated in a significant manner. Moreover, our research found that adolescents’ willingness to seek help significantly impacts their happiness, supporting the current study’s argument. A strong correlation between their happiness and work is a good predictor of their happiness. The R-value is 0.718, which indicates that seeking help and being happy are highly correlated among adolescents. This means that adolescents’ self-strength can account for a 52% variation in happiness. If seeking help increases by one unit, adolescents’ happiness will increase by 0.52 units. It is important to note that these results depend more and more on groups of students from two countries. They show how seeking help behaviors, and adolescent happiness is strongly associated. The current study also supported the findings of a study conducted by Suka et al. [39], which was used to measure anxiety help-seeking intentions during communications. In addition, people who took the follow-up study were asked how likely they would get treatment for anxiety and how likely they would get help for their psychological health [40].

The current quantitative study compared Pakistani and Chinese adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness. Which revealed that Pakistani adolescents had a higher level of self-strength, seeking help and happiness. The current study has strong applicability in the field of education for managing adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness. It is essential to make them feel comfortable in their classrooms so that they may learn better social, emotional, and intellectual skills to improve their mental health and sociability in the classrooms. The current study also had a few limitations: the data was only collected using the questionnaire, which may lead to biased responses. This limitation can be managed in future research by validating the data through participants’ observations. This phenomenon may be investigated further. Future researchers can investigate the factors which contribute. There is a lack of research on the study variables, but it can be enhanced, and qualitative and mixed-method research approaches can also be deployed to replicate the study. As Chinese adolescents have a lower level of self-strength, seeking help and happiness can be improved, and the Chinese Government can take further steps to improve their elementary school education. On the other hand, the Pakistani school education department can seriously consider transforming the kind of self-strength, seeking help and happiness into their adult ones to develop a peaceful and prosperous society.

The focus of the current paper was to compare Pakistani adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness with Chinese adolescents’ self-strength, seeking help, and happiness. With the help of parametric statistics, it was witnessed that Pakistani Adolescents had better self-strength, seeking help and happiness than their counterparts. Moreover, this difference was also statistically significant. The current study’s second and third hypotheses were designed to investigate the effect of self-strength and seeking help on their happiness. It was also concluded that both variables significantly affected their happiness. And also significant predictors of their happiness.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by “13th Five-Year Plan” of National Education Science in China (No. BBA200033).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Simon, P. (2020). Enabling relations as determinants of self-satisfaction in the youth: The path from self-satisfaction to pro-social behaviors as explained by strength of inner self. Current Psychology, 39(2), 656–664. DOI 10.1007/s12144-018-9791-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Rahmatullah, A. S. (2021). Kyai’s psychological resilience in the perspective of pesantren: Lesson from Indonesia. Journal Pendidikan Islam, 10(2), 235–254. [Google Scholar]

3. Lenka, D. R. M. (2021). The impact of emotional intelligence in the digital age. Psychology and Education Journal, 58(1), 1844–1852. DOI 10.17762/pae.v58i1.1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Azizah, N., Wibowo, M. E., Purwanto, E. (2019). The effectiveness of strength based intervention motivational interviewing group counseling to improve students’ self compassion. Journal Bimbingan Konseling, 8(4), 189–193. [Google Scholar]

5. Kumar, D. (2020). Adolescents’ personality traits in context of teachers’ ethics and responsibility. Ideal Research Review, 21(21). https://journalirr.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/1.-Dinesh-Kumar-.pdf. [Google Scholar]

6. Lavy, S. (2020). A review of character strengths interventions in twenty-first-century schools: Their importance and how they can be fostered. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 573–596. DOI 10.1007/s11482-018-9700-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Suroso, E., Hidayah, N., Ali, A. J. (2021). Discovering self strength, building entrepreneurial spirit among senior high school students at Kembangan subdistrict West Jakarta. ICCD, 3(1), 121–125. DOI 10.33068/iccd.vol3.iss1.318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Thurasingam, V., Bakar, A. B. (2020). Level of resilience among academically intelligent students. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research, 54(3), 195–203. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhang, L. (2018). Cultivating the therapeutic self in China. Medical Anthropology, 37(1), 45–58. DOI 10.1080/01459740.2017.1317769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sulistyaningsih, W., Ervika, E. (2018). Effective of mindfulness training for increasing happiness in adolescence’ with authoritarian parenting style.International Research Journal of Advanced Engineering and Science, 3(3), 167–170. [Google Scholar]

11. Anyan, F., Hjemdal, O. (2016). Adolescent stress and symptoms of anxiety and depression: Resilience explains and differentiates the relationships. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203, 213–220. DOI 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Medcalf, B. (2017). Exploring the music therapist’s use of mindfulness informed techniques in practice. Australian Journal of Music Therapy, 28, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

13. Ford, B. Q., Shallcross, A. J., Mauss, I. B., Floerke, V. A., Gruber, J. (2014). Desperately seeking happiness: Valuing happiness is associated with symptoms and diagnosis of depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(10), 890–905. DOI 10.1521/jscp.2014.33.10.890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mahon, N. E., Yarcheski, A. (2002). Alternative theories of happiness in early adolescents. Clinical Nursing Research, 11(3), 306–323. DOI 10.1177/10573802011003006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Karabenick, S. A., Newman, R. S. (2013). Help seeking in academic settings: Goals, groups, and contexts. Routledge, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

16. Hendriks, T., Warren, M. A., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T. et al. (2019). How WEIRD are positive psychology interventions? A bibliometric analysis of randomised controlled trials on the science of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(4), 489–501. DOI 10.1080/17439760.2018.1484941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Eccles, J. S., Wang, M. T. (2016). What motivates females and males to pursue careers in mathematics and science? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(2), 100–106. DOI 10.1177/0165025415616201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Amemiya, J., Wang, M. T. (2017). Transactional relations between motivational beliefs and help seeking from teachers and peers across adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(8), 1743–1757. DOI 10.1007/s10964-016-0623-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Schenke, K., Lam, A. C., Conley, A. M., Karabenick, S. A. (2015). Adolescents’ help seeking in mathematics classrooms: Relations between achievement and perceived classroom environmental influences over one school year. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 133–146. DOI 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ryan, A. M., Shin, H. (2011). Help-seeking tendencies during early adolescence: An examination of motivational correlates and consequences for achievement. Learning and Instruction, 21(2), 247–256. DOI 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Järvelä, S. (2011). How does help seeking help?–New prospects in a variety of contexts. Learning and Instruction, 21(2), 297–299. DOI 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shoshani, A., Steinmetz, S. (2014). Positive psychology at school: A school-based intervention to promote adolescents’ mental health and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(6), 1289–1311. DOI 10.1007/s10902-013-9476-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. McDermott, R. C., Cheng, H. L., Wong, J., Booth, N., Jones, Z. et al. (2017). Hope for help-seeking: A positive psychology perspective of psychological help-seeking intentions. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(2), 237–265. DOI 10.1177/0011000017693398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Norrish, J. M., Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2009). Positive psychology and adolescents: Where are we now? Where to from here? Australian Psychologist, 44(4), 270–278. DOI 10.1080/00050060902914103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ha, Q. (2017). ‘An early morning’ and ‘moonlit night’ by Thach Lam translated from the Vietnamese by Quan Manh Ha. Asian Literature and Translation, 4(1). DOI 10.18573/j.2017.10133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Casadaban, A. B. (2010). Self strength work. www.PerformanceAndRealization.com. [Google Scholar]

27. Schore, A. N. (2009). Right brain affect regulation: An essential mechanism of development, trauma, dissociation, and psychotherapy. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

28. Horner, R. (2020). Men’s help-seeking behavior (Doctoral Dissertation). City University of Seattle. [Google Scholar]

29. Schenke, K., Ruzek, E., Lam, A. C., Karabenick, S. A., Eccles, J. S. (2018). To the means and beyond: Understanding variation in students’ perceptions of teacher emotional support. Learning and Instruction, 55, 13–21. DOI 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Leach, L. S., Rickwood, D. J. (2009). The impact of school bullying on adolescents’ psychosocial resources and help-seeking intentions. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 2(2), 30–39. DOI 10.1080/1754730X.2009.9715702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Toren, S. J., van Grieken, A., Lugtenberg, M., Boelens, M., Raat, H. (2020). Adolescents’ views on seeking help for emotional and behavioral problems: A focus group study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 191. DOI 10.3390/ijerph17010191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Vidourek, R. A., King, K. A., Nabors, L. A., Merianos, A. L. (2014). Students’ benefits and barriers to mental health help-seeking. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 1009–1022. DOI 10.1080/21642850.2014.963586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Proctor, C., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J. (2010). Very happy youths: Benefits of very high life satisfaction among adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 98(3), 519–532. DOI 10.1007/s11205-009-9562-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Keyes, C. L. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95–108. DOI 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lambert, M., Fleming, T., Ameratunga, S., Robinson, E., Crengle, S. et al. (2014). Looking on the bright side: An assessment of factors associated with adolescents’ happiness. Advances in Mental Health, 12(2), 101–109. DOI 10.1080/18374905.2014.11081888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Huitt, W., Hummel, J. (2003). Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. Educational Psychology Interactive, 3(2), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

37. Mills, G. E., Gay, L. R. (2019). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications, 07458. One Lake Street, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

38. Shin, H. I., Jeon, W. T. (2011). “I’m Not happy, but I don’t care”: Help-seeking behavior, academic difficulties, and happiness. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 23(1), 7–14. DOI 10.3946/kjme.2011.23.1.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Suka, M., Yamauchi, T., Yanagisawa, H. (2018). Comparing responses to differently framed and formatted persuasive messages to encourage help-seeking for depression in Japanese adults: A cross-sectional study with 2-month follow-up. BMJ Open, 8(11), e020823. DOI 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Asher, S. N., Ur Rehman Khattak, N., Haider, S. K. F. (2015). Credit improves self-confidence among females: A case study of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Putaj Humanities & Social Sciences, 22(1), 33–43. [Google Scholar]

41. Ab Razak, N. H., Johari, K. S. K., Mahmud, M. I., Zubir, N. M., Johan, S. (2018). Module of cognitive behavior play therapy on decision making skills and resilience enhancement (CBPT module). International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development. DOI 10.6007/IJARPED/v7-i4/4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Nizam, H., Ali, S. M. (2021). Perceived barriers and facilitators to access mental health services among Pakistani adolescents. BioSight, 2(2), 4–12. DOI 10.46568/bios.v2i2.46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Inam, A., Fatima, H., Naeem, H., Mujeeb, H., Khatoon, R. et al. (2021). Self-compassion and empathy as predictors of happiness among late adolescents. Social Sciences, 10(10), 380. DOI 10.3390/socsci10100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kholifah, S., Margono, H. M., Fitryasari, R., Yusuf, A. (2020). Effect of therapeutic group therapy on self-confidence among adolescent with orphanages in mojokerto regency. International Journal of Nursing and Health Services (IJNHS), 3(1), 72–79. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools