Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Effects of Job Insecurity, Emotional Exhaustion, and Met Expectations on Hotel Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Test of a Serial Mediation Model

1 Faculty of Tourism, Eastern Mediterranean University, Gazimagusa, 99628, Turkey

2 Department of Management and Business Administration, Faculty of Economics, “Constantin Brancusi” University of Targu-Jiu, Targu-Jiu, 210135, Romania

* Corresponding Author: Osman M. Karatepe. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(2), 287-307. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2022.025706

Received 26 July 2022; Accepted 24 October 2022; Issue published 02 February 2023

Abstract

There are a plethora of empirical pieces about employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. However, the extant literature has either ignored or not fully examined various factors (e.g., negative or positive non-green workplace factors) that might affect employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. Realizing these voids, the present paper proposes and tests a serial mediation model that examines the interrelationships of job insecurity, emotional exhaustion, met expectations, and proactive pro-environmental behavior. We used data gathered from hotel customer-contact employees with a time lag of one week and their direct supervisors in China. After presenting support for the psychometric properties of the measures via confirmatory analysis in LISREL 8.30, the abovementioned linkages were gauged using the PROCESS plug-in for statistical package for social sciences. The findings delineated support for the hypothesized associations. Specifically, emotional exhaustion and met expectations partly mediated the effect of job insecurity on proactive pro-environmental behavior. More importantly, emotional exhaustion and met expectations serially mediated the influence of job insecurity on proactive pro-environmental behavior. These findings have important theoretical implications as well as significant implications for diminishing job insecurity, managing emotional exhaustion, increasing met expectations, and enhancing eco-friendly behaviors.Keywords

Protecting and preserving the ecological environment has become a priority in many organizations’ agendas [1]. However, management of these organizations cannot reach the abovementioned environmental goals without the involvement of employees in the company’s environmental sustainability program. That is, employees should help the organization to achieve these goals by displaying pro-environmental behavior (PEB) [2]. Proactive PEB, which is defined as “…the extent to which employees take initiative to engage in environmentally-friendly behaviors that move beyond the realm of their required work tasks” [3, p. 158], enables employees to make constructive suggestions regarding the solutions of environmental problems and engage in environmentally-friendly actions.

One of the most critical hindrance stressors in today’s competitive market environment that may hamper employees’ proactive PEBs is job insecurity (JIS) [4]. JIS, which highlights the “…perceived powerlessness to maintain desired continuity in a threatened job situation” [5, p. 438], is prevalent in many industries including the hospitality and tourism industry [6–11], and has been intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic [12–14]. Employees suffering from heightened JIS exhibit emotional exhaustion [13], which denotes the depletion of emotional resources as a result of excessive job demands [15]. Emotional exhaustion is a work-related strain, is the initiator of the burnout syndrome, and is experienced by a number of individuals as a consequence of excessive work or nonwork-related demands [13,15–19].

Met expectations highlight “…the discrepancy between what a person encounters on [this] job in the way of positive and negative experiences and what he expected to encounter” [20, p. 152]. Once employees’ expectations about various factors in the workplace are met, this may trigger their willingness to engage in eco-friendly behaviors. This is due to the fact that employees are likely to exhibit positive behaviors or attitudes such as an increase in job satisfaction and a decrease in quitting intentions if their expectations concerning the financial aspects, the kind and amount of work they have been doing, and/or the quality of the relationship with their supervisors and coworkers are substantially met [21,22].

1.1 Purpose and Research Questions

Taking note of what has been delineated above, our paper proposes and tests a serial mediation model. Specifically, the objectives of our paper are to assess: (1) the impact of JIS on proactive PEB; (2) emotional exhaustion as a mediator between JIS and proactive PEB; (3) met expectations as a mediator of the link between JIS and proactive PEB; and (4) emotional exhaustion and met expectations as the two mediators linking JIS to the aforesaid PEB in a sequential manner.

The objectives of this paper are to address the following research questions:

(1) What is the nature of the relationship between JIS and PEB?

(2) Does JIS influence PEB through the mediating role of emotional exhaustion?

(3) Does JIS affect PEB through the mediating role of met expectations?

(4) Do emotional exhaustion and met expectations serially mediate the association between JIS and PEB?

The contributions of our paper are the following: First, there is a growing amount of literature on PEBs. However, there are still many unanswered questions. Specifically, there is limited knowledge about the impact of JIS on employees’ PEBs. As a matter of fact, there is limited research about the impact of JIS on performance-related outcomes [10]. Excluding Karatepe’s [4] work which reported that JIS impeded hotel employees’ green recovery performance and proactive PEBs, past and recent writings do not shed light on whether employees suffering from the threat of job loss in the future do not contribute to the hotel’s environmental sustainability efforts through their PEBs [23,24]. Using conservation of resources (COR) theory, we contend that JIS is a stressor that impedes employees’ proactive PEBs.

Second, there are still calls for additional research concerning the psychological mechanism relating JIS to employee outcomes [4,19,25,26]. Therefore, our paper unravels the psychological mechanism through which JIS is associated with proactive PEB. To elucidate this, we use emotional exhaustion and met expectations as the two mediators. Under the umbrella of stress-strain-outcome model [27], we propose that emotional exhaustion (strain) mediates the link between JIS (stressor) and proactive PEB (outcome). In light of psychological contract theory [28], we also propose that met expectations mediate the impact of JIS on the aforesaid outcome.

Third, more importantly, we test the serial mediating effects of emotional exhaustion and met expectations on proactive PEB. With the assessment of these serial mediating impacts, it would be possible to figure out whether multiple mediators link JIS to such an important PEB. Our paper is the first of its kind by gauging these serial mediating effects.

Lastly, our paper adds to the literature on met expectations by proposing that JIS and emotional exhaustion erode met expectations, while met expectations foster proactive PEB. Though some writings present evidence about the linkage between emotional exhaustion and met expectations or vice versa [29,30], to the best of our knowledge, no empirical study has gauged the impact of JIS on met expectations and the linkage between met expectations and proactive PEB so far.

2 Literature Review and Hypotheses

A careful analysis of the extant literature reveals limited empirical studies that have tested the negative and positive non-green workplace factors influencing employees’ PEBs [31–34]. This is surprising because employees would display eco- or environmentally-friendly behaviors once they feel job security and can handle problems emanating from work-related strain. They would also exhibit such behavioral outcomes once they perceive that their expectations regarding the physical conditions in the workplace, financial aspects, and/or the quality of relations with supervisors and coworkers are met. As can be observed from the review of the relevant literature given below, none of the empirical pieces has explored the effects of JIS, emotional exhaustion, and met expectations simultaneously on PEBs so far.

Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt [5] have defined JIS as “…potential loss of continuity in a job situation…loss of some subjectively important feature of the job” (p. 440). In view of this definition, Hellgren et al. [35] categorized JIS into quantitative JIS and qualitative JIS. Employees experience qualitative JIS when they have worries about the loss of important job features such as limited career opportunities and reduced salary [36]. They experience quantitative JIS when they have worries about losing their job in the future [35,36]. In this study, we focus on quantitative JIS since the hospitality industry is noted for high employee turnover [37].

JIS causes many undesirable consequences among employees. Liao et al. [38] argued that workers are unlikely to exhibit voice behavior when they feel threatened about negative outcomes that may arise from their voice behaviors. This denotes the risk of job loss in an organization. Studies conducted with service employees also present the deleterious effect of JIS on various outcomes. For example, Wang et al.’s [39] research in China illustrated that JIS was a partial mediator between authentic leadership and surface acting among hotel employees. Chen et al. [40] reported that JIS partly mediated the link between fear of COVID-19 and emotional exhaustion among U.S. restaurant frontline employees. A study of flight attendants in South Korea indicated that supervisor incivility aggravated JIS, which in turn impeded service performance [41]. Another study conducted in Taiwan revealed that both role overload and job security partly mediated effect of leader-member exchange on hotel employees’ work engagement [42]. Ugwu et al.’s [43] research in Nigeria denoted that JIS diminished bank employees’ psychological well-being, while core self-evaluations and employability fostered their psychological well-being. A study of nurses in China documented that presenteeism behavior partly mediated the positive link between JIS and emotional exhaustion [44]. It was reported that COVID-19 exacerbated hospitality employees’ feelings of JIS in the Middle East and African region, while JIS heightened their anxiety and alienation [45]. In another research, [46] found that job tension served as a partial or full mediator of the impact of JIS on trust in organization and proclivity to display nonattendance among hotel employees during COVID-19 in Turkey.

Emotional exhaustion is the first stage of the burnout syndrome and is likely to occur as a consequence of heightened job demands [15,30]. A comprehensive review of the relevant literature presents evidence about the factors affecting emotional exhaustion as well as its consequences. Specifically, the findings of an empirical research conducted with nurses in Pakistan illustrated that emotional exhaustion mediated the effect of state anger and job stress on quitting intentions [47]. Sahi et al.’s [48] recent research in the financial services industry in India showed that psychological empowerment partially mediated the link between emotional exhaustion and employee engagement. Another recent research illustrated that emotional exhaustion partly mediated the influence of qualitative JIS on hotel employees’ job embeddedness in Turkey [49].

Schumacher et al.’s [50] research carried out in Belgium disclosed that fairness and emotional exhaustion partly mediated the relationship of JIS to affective commitment and psychosomatic complaints among bank employees during organizational change. Ul Ain et al.’s [51] research among employees in information technology and education settings in Pakistan denoted that emotional exhaustion was a partial mediator between knowledge-hiding behavior and extra-role performance. Said et al. [52] reported that mindfulness partly mediated the association between workplace bullying and emotional exhaustion for a sample of hotel employees in Tanzania. Another hotel industry-related study in Vietnam demonstrated that JIS partly mediated the effect of health risk COVID-19 on emotional exhaustion [53].

Based on a detailed review of the relevant literature, it seems that scholars in the field of hospitality and tourism management have not explored met expectations and its relationship to stressors and strain such as JIS and emotional exhaustion, and green behavioral outcomes such PEB. Specifically, Babakus et al.’s [21] research in the U.S. revealed that compensation, job satisfaction, and perceived organizational support positively influenced salespeople’s met expectations and role conflict mitigated met expectations. Their research further documented that salespeople’s met expectations exerted a positive impact on their organizational commitment. In the same setting in the same country, Grant et al. [54] showed that role ambiguity lessened met expectations. One of the past writings also indicated that expatriate salespeople’s met expectations fostered their job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and job involvement [55]. Evidence obtained from higher education in the United Arab Emirates highlighted that high levels of met expectations resulted in better job satisfaction and organizational commitment as well as an increase in organizational trust [56]. Rosing et al.’s [57] empirical investigation carried out among firefighters in Germany revealed that met follower expectations acted as a partial mediator between leader trait self-control and follower trust in the leader. Recent research carried out in Bosnia and Herzegovina revealed that employees’ fulfillment of expectations about their job enhanced overall job satisfaction [58].

In addition, Proost et al. [29] demonstrated that emotional exhaustion was a mediator between unmet expectations and proclivity to leave for a sample of primary school teachers in Belgium. A past meta-analytic work by Lee et al. [30] demonstrated a weighted mean correlation of 0.53 between unmet expectations and emotional exhaustion.

2.4 Pro-Environmental Behavior

Figuring out the factors that influence employees’ PEBs is critically important because management of service companies cannot reach their green initiatives and environmental goals without obtaining support from employees and having their engagement in PEBs [1–2,59]. Research indicates that PEB actions of hospitality companies seems to be prevalent among countries in Western Europe where hotels “…are more likely to have legislation requirements and public support as an incentive to adopt pro-environmental measures in their business operations.” [60, p. 2501].

Past and recent writings reported various factors affecting employees’ eco-friendly behaviors. For instance, Pinzone et al. [61] demonstrated that green goal difficulty partly mediated the link between green training and organizational citizenship behavior toward the environment, while perceived green organizational support partly mediated the association between green training and job satisfaction among healthcare professionals in Italy. Karatepe et al.’s [1] research in both Turkish and Korean samples disclosed that green work engagement partly mediated the effect of management commitment to the ecological environment on hotel employees’ task-related and proactive PEBs, while it completely mediated the link between management commitment to the ecological environment and their green creativity. A study done in the hotel industry in Northern Cyprus indicated that connectedness to nature was a partial mediator between workplace spirituality and organizational citizenship behavior toward the environment [62]. Ogretmenoğlu et al. [63] reported that green transformational leadership fostered hotel employees’ green creativity and organizational citizenship toward the environment in Turkey. A study of employees in the manufacturing industry in China indicated that green human resource management and corporate environmental strategy fueled green climate that in turn enhanced PEBs [64].

In addition, evidence emanating from a study in the bank industry in Pakistan documented that corporate social responsibility initiatives strengthened employees’ perceptions of servant leadership, which in turn fostered their PEBs [65]. Excluding the one that has examined the effect of JIS on hotel employees’ PEBs [4], as can be observed in Lin et al.’s [66] systematic review, JIS and met expectations have not been investigated as predictors of PEBs so far.

2.5.1 Job Insecurity and Pro-Environmental Behavior

According to COR theory, resources include “…objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies that are valued in their own right, or that are valued because they act as conduits to the achievement or protection of valued resources…” [67, p. 339]. Employees strive to obtain and protect their valued resources since they may use them to cope with difficulties surfacing from stressors at work. JIS is one these stressors. As COR theory posits, excessive or heightened demand and/or lack of resources within the workplace result in negative employee outcomes [68]. This is due to the fact that employees with limited resources may not be able to handle problems associated with JIS and therefore exhibit poor behavioral outcomes. Such employees may not prefer to expend their scarce resources to cope with JIS and therefore display undesirable outcomes.

Evidence indicated that JIS reduced employees’ job performance in the manufacturing industry in China [69]. Past research also revealed that JIS impeded hotel workers’’ job performance in Northern Cyprus [70]. Etehadi et al.’s [71] work illustrated that JIS diminished hotel workers’ service recovery performance and service innovative behavior in Turkey. Based on COR theory and these findings, we surmise that employees having fear of job loss in the organization in the future would not prefer to expend their scarce resources to deal with JIS, and would not be willing to engage in eco-friendly behaviors. Accordingly, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 1: JIS relates negatively to hotel employees’ proactive PEBs.

2.5.2 Emotional Exhaustion as a Mediator

The stress-strain-outcome model provides guidance to develop the hypothesis that pertains to emotional exhaustion as a mediator between JIS and proactive PEB [27]. Stress refers to“…environmental stimuli (objective events) that are perceived and interpreted by the actor as troublesome and potentially disruptive” [72, p. 111]. Strain is described as “…disruptive impacts on actor concentration, physiology, and emotion…” [72, p. 111]. Koeske et al. [72] defined outcomes as “enduring behavioral or psychological consequences of prolonged stress and strain…” [p. 111]. Based on this model, JIS is a hindrance stressor that aggravates emotional exhaustion [73] and disrupts employees’ behavioral outcomes. The relationship between JIS and emotional exhaustion can also be explained via transactional theory of stress [74]. Employees’ perceptions of the work environment shape their emotional experiences. Appraisal of JIS as a stressful demand impedes employees’ personal growth and development. Under these conditions, they experience heightened emotional exhaustion [75]. The behavioral outcome used in our paper is proactive PEB. That is employees who have the fear of losing their jobs in the future experience elevated levels of emotional exhaustion that in turn lead to poor eco-friendly behavior.

The literature supports the use of this model. For example, Hsieh et al. [76] reported that ostracizing behaviors heightened Taiwanese restaurant employees’ job tension that in turn resulted in higher proclivity to display nonattendance. Another study indicated that customer unfriendliness aggravated Filipino call center employees’ emotional exhaustion, leading to turnover intentions at high levels [77]. In view of the stress-strain-outcome model and the abovementioned evidence, we contend that hotel employees are beset with heightened JIS and therefore suffer from depletion of emotional resources. These employees in turn are unwilling to engage in eco-friendly behaviors that would help the organization to reach its green initiatives and environmental goals. Thus, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 2: Emotional exhaustion mediates the impact of JIS on hotel employees’ proactive PEBs.

2.5.3 Met Expectations as a Mediator

In the current paper, we propose that met expectations mediate the link between JIS and proactive PEB. The hypothesis concerning this mediating effect can be developed under the umbrella of psychological contract theory [28]. Specifically, this theory contends that employees’ unmet expectations are associated with breaches in psychological contract. These breaches can be in the form of reneging (i.e., the company does not keep its promises) or incongruence (i.e., employees and managers have different perceptions about an obligation) [28]. Employees who perceive that there are breaches in the psychological contract that have emanated from the threat of JIS in the workplace would not contribute to the organization via PEBs. In other words, when employees’ job expectations are unmet due to heightened JIS or their job expectations differ substantially from what they observe and experience in the workplace, they are unlikely to have the motivation to engage in eco-friendly behaviors. This is not surprising because met expectations play a crucial role in psychological contracts [78]. Employees finding that their expectations in terms of the financial aspects, the type of work, the quality of supervision, and the number of assignments are not met they may consider these issues as breaches in psychological contract. Under these conditions, they are unlikely to display PEBs. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3: Met expectations mediate the impact of JIS on hotel employees’ proactive PEBs.

The aforesaid hypotheses 1–3 developed in light of COR [67] and psychological contract [28] theories and stress-strain-outcome model [27] as well as the findings regarding the relationship of emotional exhaustion to met expectations [30] implicitly suggest that both emotional exhaustion and met expectations serially mediate the impact of JIS on PEB. Broadly speaking, JIS implies a threat to employees’ well-being. This is because of the fact that employees who feel insecure about their jobs try to complete their tasks in an environment which is stressful and challenging [13,71]. Under these circumstances, they are highly emotionally exhausted [40]. Employees experiencing heightened emotional exhaustion as a result of JIS would have unmet job expectations. That is, the risk of potential job loss in an organization together with the drainage of emotional resources would erode employees’ expectations in the form of the quality of relations with coworkers and supervisors, the amount and type of work, career, and physical conditions. According to Houkes et al. [79], unmet career expectations can force employees to display withdrawal behaviors. When employees’ actual job experience within the organization show that their expectations are not met due to high levels of emotional exhaustion arising from JIS, they would not be eager to engage in PEBs. When the organization fuels an environment that poses the potential loss of employment, income, and social status and has a pool of employees who are beset with emotional exhaustion surfacing from JIS and whose expectations are unmet, these employees are unlikely to engage in environmentally-friendly behaviors that would help the organization to attain its environmental goals and green initiatives. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 4: Emotional exhaustion and met expectations mediate the impact of JIS on hotel employees’ proactive PEBs in a sequential manner.

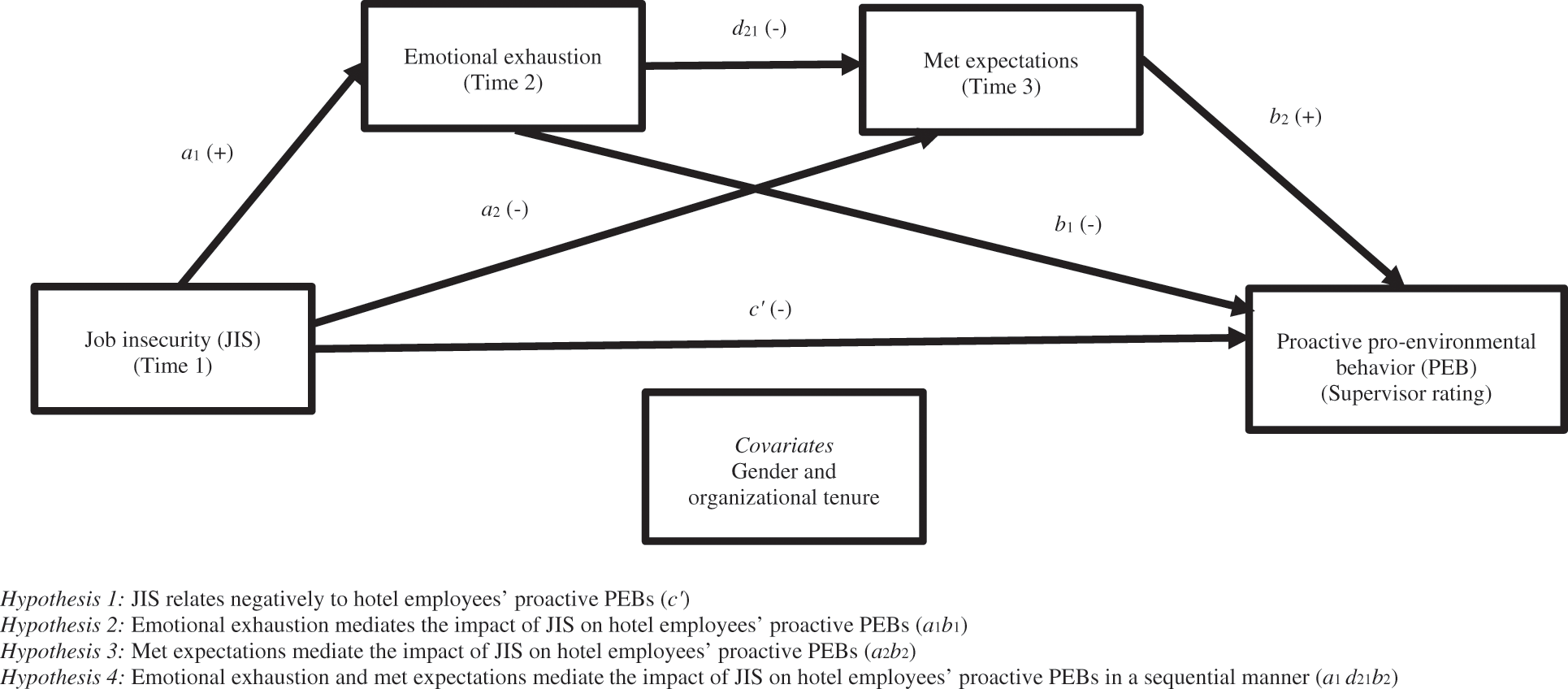

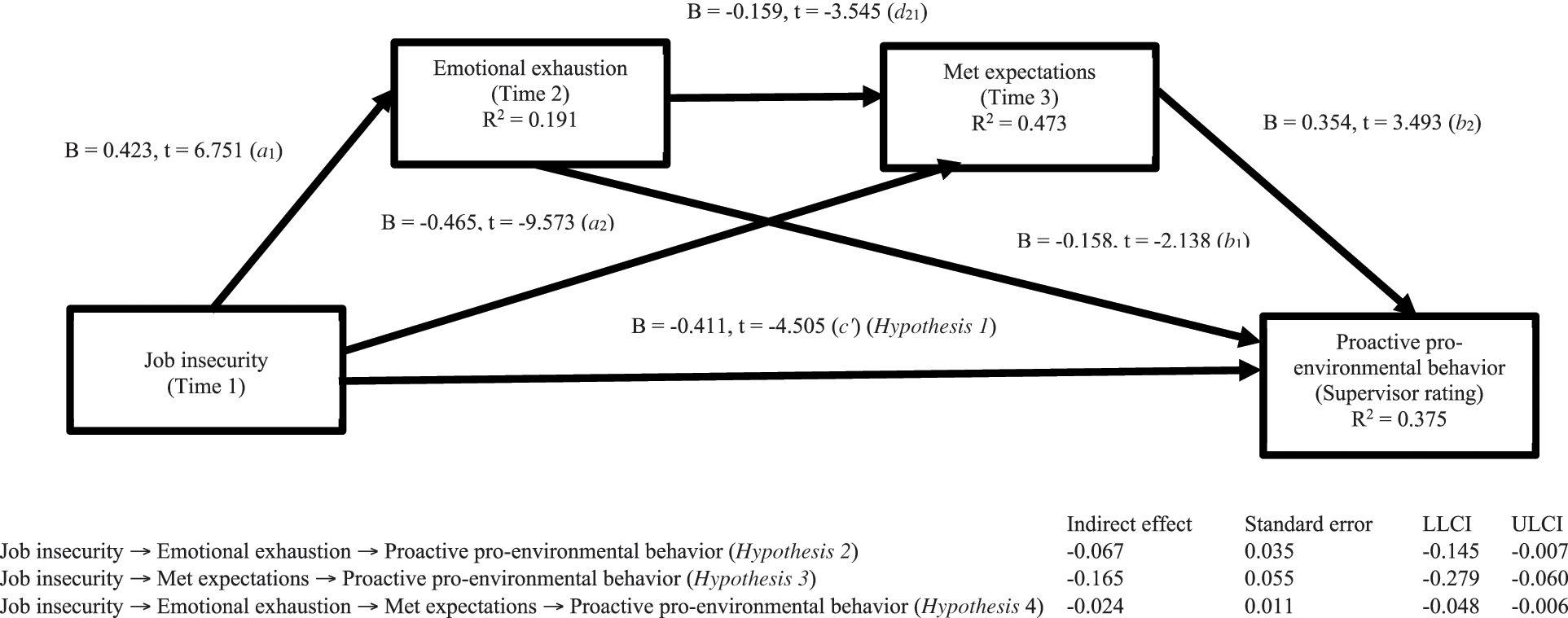

The research (serial mediation) model guiding our study is given in Fig. 1. JIS is a hindrance stressor exacerbating employees’ emotional exhaustion, reducing their met expectations, and eroding their proactive PEBs. As demonstrated in the model, emotional exhaustion and met expectations act as the two mediators between JIS and proactive PEBs. These variables serially mediate the impact of JIS on hotel employees’ proactive PEBs. Gender and organizational tenure are used as covariates due to their potential confounding effects on emotional exhaustion, met expectations, and proactive PEBs [1,4,40,49].

Figure 1: Serial mediation model

3.1 Sample and Data Collection

In this paper, judgmental sampling, which refers to “picking cases that are judged to be typical of the population in which we are interested, assuming that errors of judgment in the selection will tend to counterbalance one another” [80, p. 136], was utilized to identify the sample of the research. Accordingly, the participants included customer-contact employees (e.g., front desk agents, food servers) in the international four- and five-star hotels in Guangzhou in China. There are at least three reasons for choosing customer-contact hotels and these hotel types. First, hotel employees including the ones in customer-contact positions feel threatened about the potential job loss in their organization in the future [4,14]. Second, customer-contact employees are faced with heightened emotional exhaustion [49,81]. Third, management of such hotels is committed to investment in environmental sustainability [1].

Out of the 21 international hotels in Guangzhou in China, only 1 international four-star and 5 international five-star hotels partook in this study. The data collection process was coordinated with the human resource managers of the aforementioned hotels. To curtail common method variance, several procedural remedies in the cover page of each questionnaire were used: “There are no right or wrong answers in this questionnaire”, “Any sort of information collected during our research will be kept confidential”, “Participation is voluntary but encouraged”, “Management of your hotel fully endorses participation”, and “Agreeing to fill out this questionnaire shows your consent.” Moreover, each participant was requested to seal the questionnaire in the envelope and place it in the designated box. More importantly, data were collected from employees via a time lag of one week in 3 waves. Employees’ proactive PEBs were rated by their immediate supervisors. Matching the questionnaires with each other was performed through the identification codes.

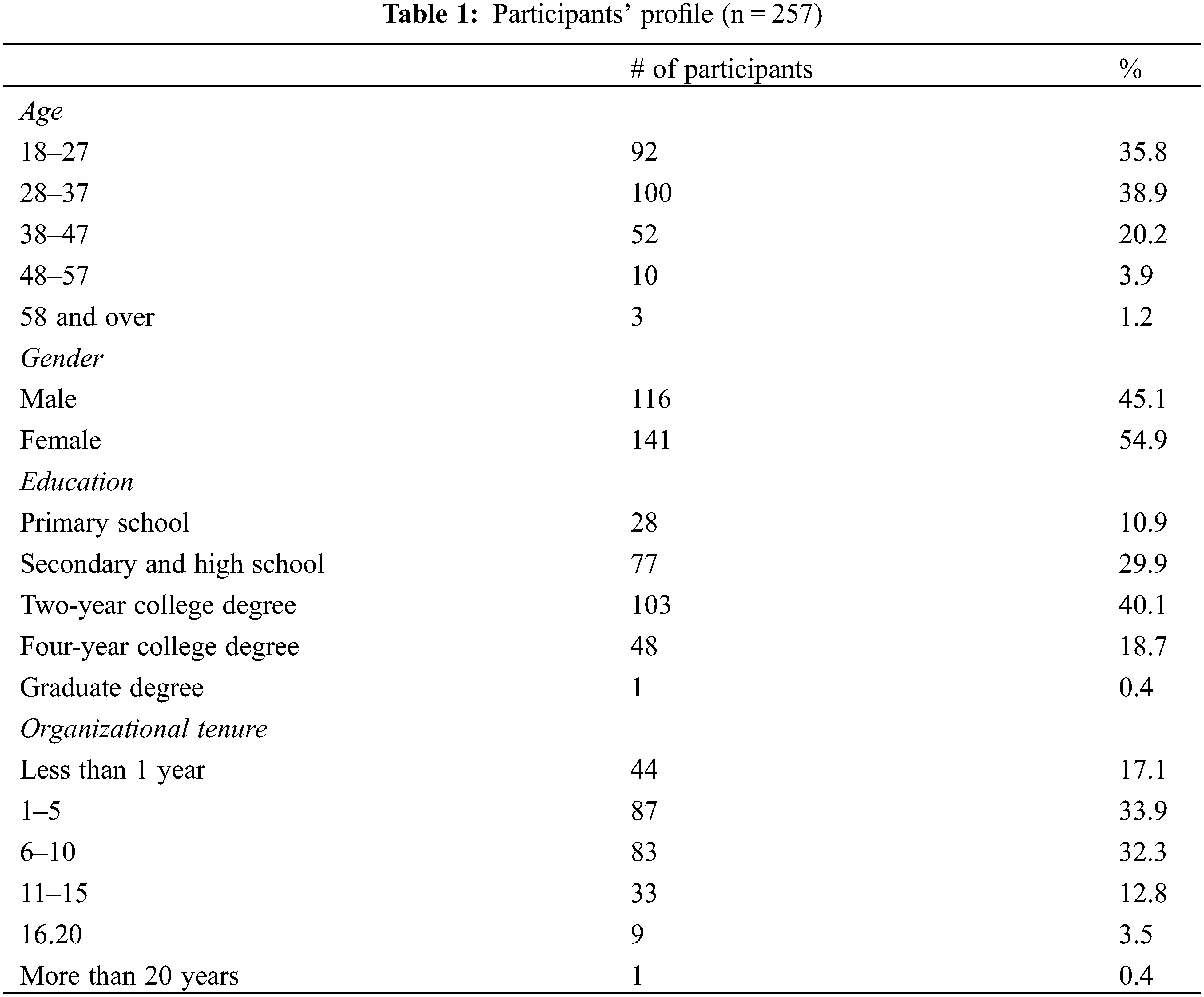

In the present research, 274 Time 1 questionnaires were distributed to employees. Two hundred and seventy-one questionnaires were returned. These employees completed the Time 2 questionnaires and were invited to fill out the Time 3 questionnaires. Two hundred and sixty-seven Time 3 questionnaires were returned. These employees’ proactive PEBs were rated by 36 supervisors. Before analyzing the data, the whole dataset was subjected to an outlier check. Ten questionnaires were discarded since they had a standardized score value of ± 3.5 [82]. Consequently, the response rate was 93.8% (257/274). The participants’ profile was given in Table 1.

The questionnaires were prepared in English and then translated into Chinese in light of the back-translation method. The back-translated Time 1, 2, and 3 questionnaires were tested with 5 employees and the supervisor questionnaire was tested with 5 supervisor during the pilot study. None of the participants reported difficulties regarding the readability and comprehension of the items. Therefore, no changes were made.

JIS (Time 1) was operationalized with four items, which were reverse-scored. These items came from Delery et al. [83]. Example items are “Employees in this job can expect to stay in the organization for as long as they wish” and “It is very difficult to dismiss an employee in this organization”. Prior empirical pieces also used this scale to measure JIS [25,71]. Responses to these items were recorded via “5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree”.

Emotional exhaustion (Time 2) was measured with eight items from Maslach et al. [84]. Example items are “I feel emotionally drained from my work” and “I feel used up at the end of the workday”. The abovementioned scale was widely utilized in the extant literature [18,85]. Responses to these items were rated on “5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree”.

Nine items from Lee et al. [86] were used to gauge met expectations (Time 3). Example items are “In general, my experiences with the kind of work that I do have been” and “In general, my experiences with the financial aspects (e.g., pay, benefits) have been”. The anchors ranged from “5 = much more than expected” to “1 = less than expected”.

Three items from Bissing-Olson et al. [3] were utilized to gauge proactive PEB (the supervisor rating). An example item is “This employee takes a chance to get actively involved in environmental protection at work”. Recent studies tapped Bissing-Olson et al.’s [3] scale to measure employees’ PEBs [1,4]. The anchors ranged from “5 = almost always” to “1 = never”. Gender was coded as “0 = male and 1 = female”. Organizational tenure was measured in six categories.

The construct measures were subjected to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to gauge their measurement properties [87–89]. Covariance matrix was tapped in LISREL 8.30 to run CFA [90]. In light of CFA results, convergent and discriminant validity as well as the internal consistency reliability were tested. The measurement model was assessed in light of the fit statistics such as “χ2/df, comparative fit index (CFI), parsimony normed fit index (PNFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)” [e.g., 82,91].

The correlations among the construct measures (observed constructs) and coefficient alphas were also reported. The hypothesized associations were tested using the model 6 in the PROCESS macro with a bootstrapped 5,000 sample size via the 95% confidence interval [92]. This is in congruence with a number of studies in the extant literature that have gauged the serial mediating effects [93,94].

4.1 Test of the Measurement Model

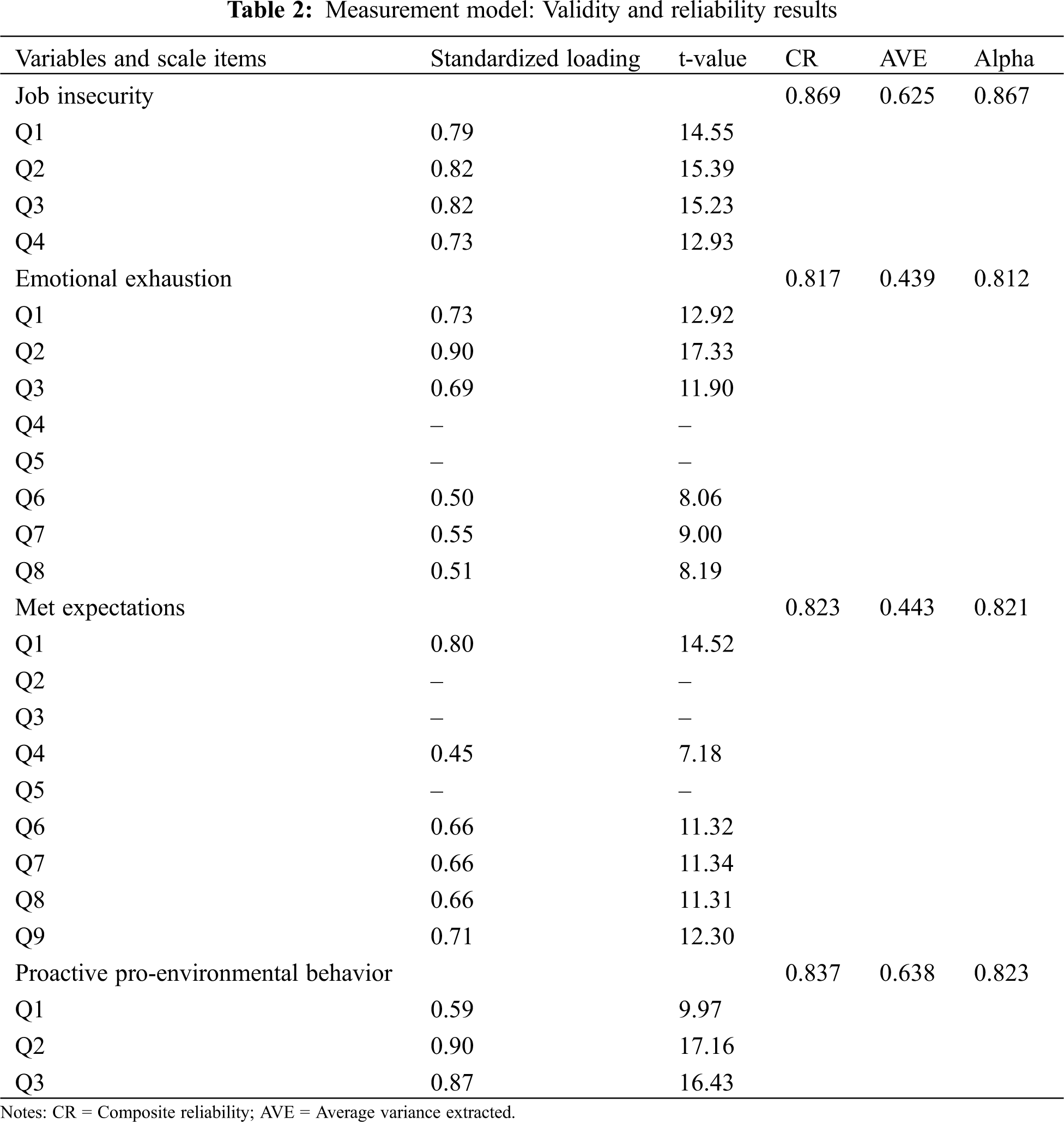

We performed CFA on all the scales simultaneously with the resulting measurement properties showing convergent and discriminant validity. Specifically, after deletion of two items from emotional exhaustion and three items from met expectations due to low standardized loadings <0.45 (Table 2) [95,96], the overall fit of the four-factor measurement model was acceptable: χ2 = 330.17, df = 146, χ2/df = 2.26; CFI = 0.92; PNFI = 0.74; SRMR = 0.067; RMSEA = 0.070. One of the items’ loadings in met expectations was 0.45 and the rest of the loadings were ≥ 0.50. This is in agreement with other studies [97]. Fig. 2 presented the results obtained from CFA in LISREL 8.30.

Figure 2: Confirmatory factor analysis results in LISREL 8.30

In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) by JIS, emotional exhaustion, met expectations, and proactive PEB was 0.625, 0.439, 0.443, and 0.638, respectively. The composite reliability score for JIS, emotional exhaustion, met expectations, and proactive PEB was 0.869, 0.817, 0.823, and 0.837. The AVE values for emotional exhaustion and met expectations were below 0.50. There are studies that have reported the AVE value below 0.50 [4,98]. However, a value of 0.40 for the AVE by a latent construct is acceptable if its composite reliability score is above the threshold [89]. The composite reliability values for these variables were >0.60 [88]. These internal consistency reliabilities were also supported by coefficient alphas, which were >0.70 [82]. Therefore, convergent validity was verified.

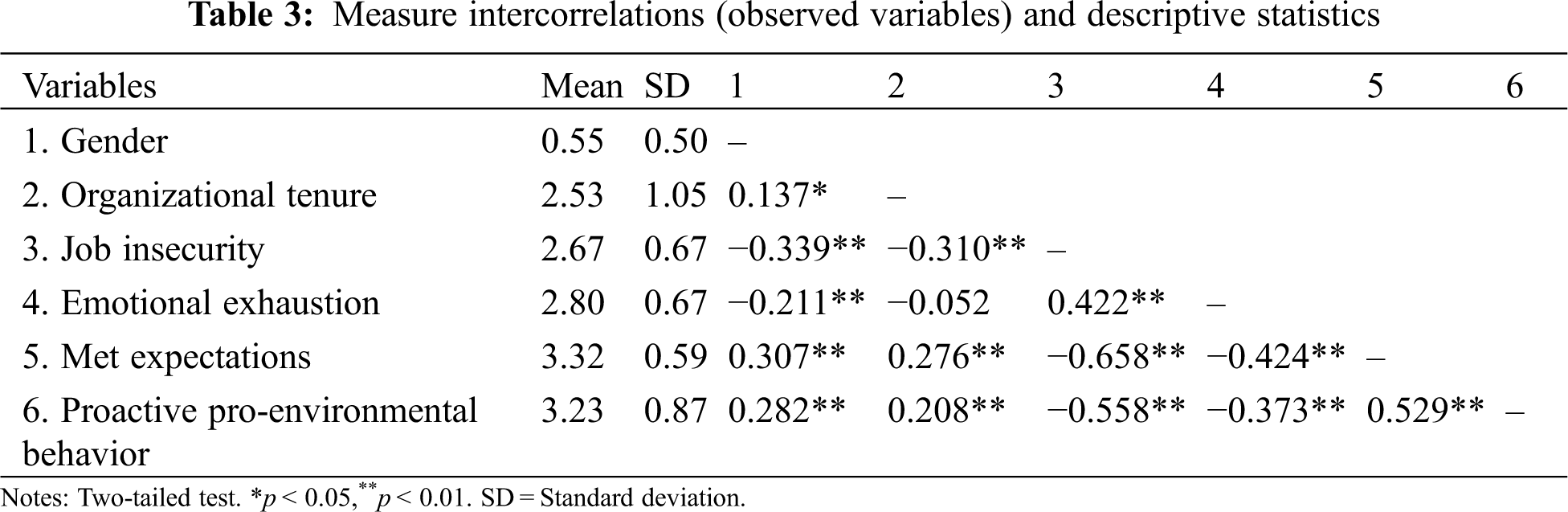

Discriminant validity was also verified using the Fornell et al.’s [89] criterion excluding the one between JIS and met expectations. Specifically, the AVE value exceeded Φ2 for the construct with every other construct. However, Φ2 for JIS and met expectations was 0.593 (−0.77 × −0.77). Therefore, we performed another analysis suggested by Anderson et al. [87]. We forced the items of JIS and met expectations into a single underlying factor (χ2 = 118.99, df = 34) and then compared it with a two-factor model (χ2 = 253.95, df = 35) using the chi-square difference test. The result was significant (Δχ2 = 134.96, Δdf = 1). Thus, discriminant validity was achieved. Table 3 gives the measure intercorrelations and descriptive statistics.

4.2 Test of the Serial Mediation Model

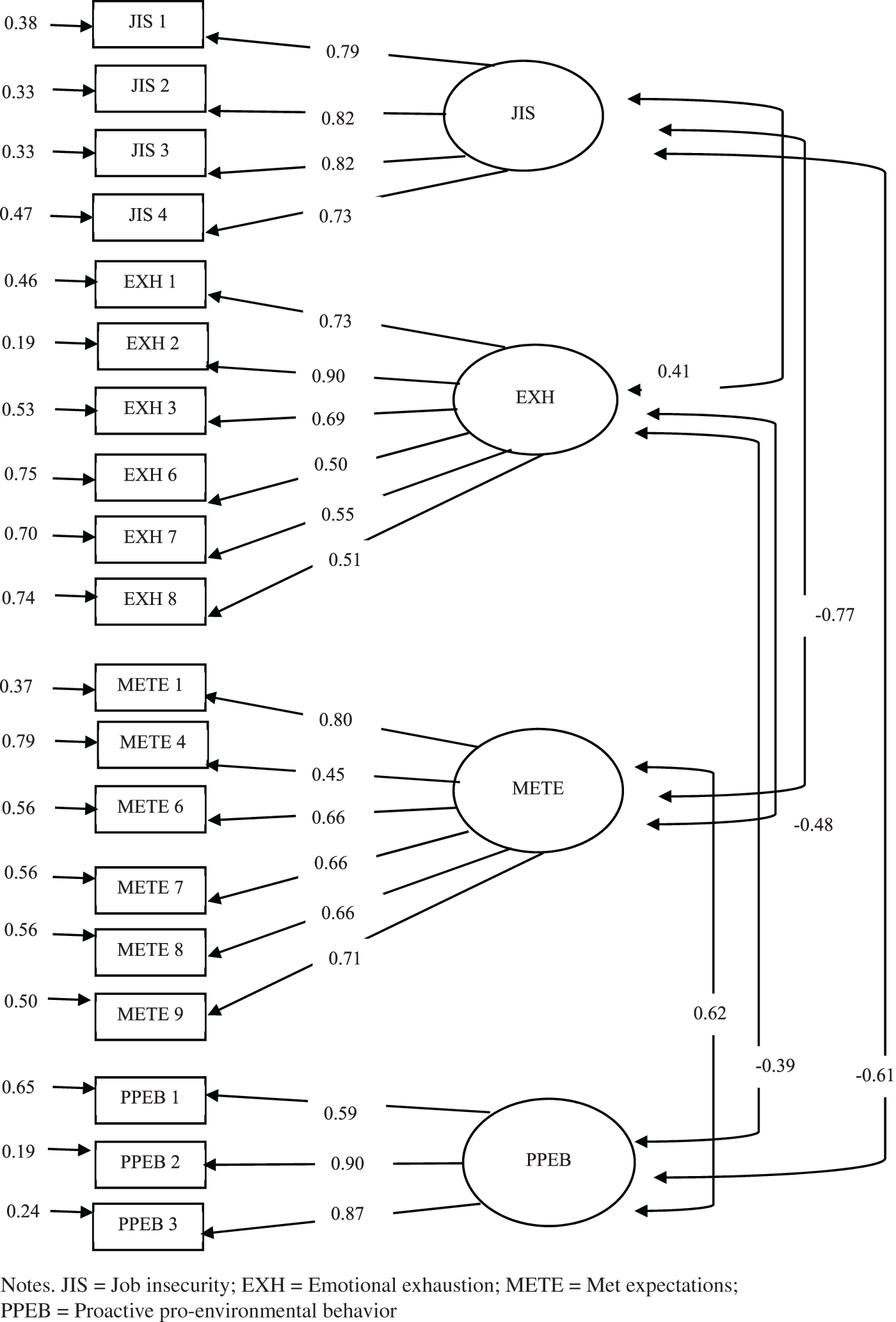

The findings were in support of all of the hypotheses and the serial mediation model given in Fig. 3 was viable. Broadly speaking, JIS was positively linked to proactive PEB (B = −0.411, t = −4.505, lower level confidence interval, LLCI = −0.591, upper level confidence interval, ULCI = −0.231). Hence, hypothesis 1 was supported. The findings illustrated that JIS had a positive impact on emotional exhaustion (B = 0.423, t = 6.751, LLCI = 0.300, ULCI = 0.546), while emotional exhaustion was negatively associated with proactive PEB (B = −0.158, t = −2.138, LLCI = −0.304, ULCI = −0.012). The indirect effect of JIS on proactive PEB via emotional exhaustion was significant and negative (B = −0.067, LLCI = −0.145, ULCI = −0.007). These findings explicitly showed that emotional exhaustion partly mediated the link between JIS and proactive PEB. Consequently, hypothesis 2 was confirmed.

Figure 3: Results: Serial mediation model

The findings were also in support of hypothesis 3, which denoted that met expectations mediated the link between JIS and proactive PEB. Specifically, JIS portrayed a negative linkage with met expectations (B = −0.465, t = −9.573, LLCI = −0.561, ULCI = −0.370), while met expectations were positively related to proactive PEB (B = 0.354, t = 3.493, LLCI = 0.154, ULCI = 0.553). The indirect impact of JIS on proactive PEB via met expectations was significant and negative (B = −0.165, LLCI = −0.279, ULCI = −0.060). Again these results explicitly revealed that met expectations partly mediated the link between JIS and proactive PEB.

According to the findings in Fig. 2, emotional exhaustion depicted a negative association with met expectations (B = −0.159, t = −3.545, LLCI = −0.248, ULCI = −0.071). Overall, the findings indicated that emotional exhaustion and met expectations serially mediated the link between JIS and proactive PEB (B = −0.024, LLCI = −0.048, ULCI = −0.006). But this serial mediating effect was partial. Hence, hypothesis 4 was confirmed.

Gender and organizational tenure did not have any significant effects on the study variables. The results explained 0.191 of the variance in emotional exhaustion, 0.473 in met expectations, and 0.375 in proactive PEB. The results with respect to the significance of the direct and mediating effects did not demonstrate any changes without the covariates.

The results from the analysis of the survey data obtained in the hotel industry in China provide strong support for all of the hypotheses. The results explicitly reveal that the serial mediation model proposed in our paper is viable. Broadly speaking, employees having worries about the loss of their jobs are unwilling to contribute to the hotel’s environmental sustainability efforts via their proactive PEBs. As posited by COR theory [67], heightened stressors such as JIS experienced by employees in an organization result in dysfunctional behaviors. This is consonant with evidence concerning the link between JIS and behavioral consequences (e.g., service recovery performance and job performance [69–71]. Since hotel employees cannot cope with problems arising from JIS, they exhibit low levels of proactive PEBs.

As highlighted in transactional theory of stress [74], hindrance stressors such as JIS thwart employees’ personal growth and development and result in heightened emotional exhaustion. Employees are unwilling to engage in proactive PEBs as a result of JIS and emotional exhaustion. The finding with respect to emotional exhaustion as a mediator between JIS and proactive PEB is not only consistent with the stress-strain-outcome model but also obtains support from other studies [27,76,77]. Specifically, employees with the experience of threat and high levels of uncertainty about their jobs are emotionally exhausted at elevated levels and therefore display diminished proactive PEBs. Such individuals do not feel comfortable with the issue of employment instability that depletes their emotional resources. Under these conditions, they are unwilling to engage in PEBs.

As claimed by psychological contract theory, when employees have unmet expectations, their unmet expectations surface from breaches in psychological contract [28]. JIS is one of the stressors that erodes employees’ expectations in the form of pay, the kind and amount of work, and/or supervision. When employees find that their expectations are unmet due to reneging or incongruence associated with employment stability, they are not eager to display proactive PEBs. By reporting the finding of a mediating effect that has not been tested so far, our paper contributes to the extant literature.

Our paper reports that emotional exhaustion and met expectations serially mediate the impact of JIS on proactive PEBs. Employees feeling a threat of job loss are emotionally exhausted at high levels and therefore have unmet expectations. Employees with unmet expectations display negative outcomes [21,29,79]. In a hotel where employees suffer from emotional exhaustion due to JIS and have unmet expectations, they are not willing to help the organization achieve its environmental goals via their proactive PEBs.

The findings of our paper enhance current knowledge in the following ways. First, JIS is a hindrance stressor eroding hotel employees’ proactive PEBs. Employees would not be willing to help the hotel to attain the environmental goals as a consequence of the threat of job loss in the future. This is a problem since hotels cannot achieve these goals without the participation of employees in the process. This is the second empirical study in the relevant literature linking JIS to employees’ proactive PEBs [4].

Second, our paper also adds to the research concerning the mediating mechanism through which JIS is associated with employee outcomes [4,19]. The findings demonstrate that emotional exhaustion mediates the link between JIS and proactive PEB. This is also true for met expectations as a mediator between JIS and the abovementioned behavioral outcome.

Third, we developed all of the hypotheses using solid theoretical underpinnings such as COR theory [67,68], stress-strain-outcome model [27], transactional theory of stress [74], and psychological contract theory [28]. We believe using these theories enabled us to develop and test the serial mediating effects. The finding concerning emotional exhaustion and met expectations as the serial mediators between JIS and proactive PEB contributes to the literature. That is, employees with the fear of job loss in the hotel in the future are highly emotionally exhausted and therefore have unmet expectations (e.g., insufficient pay, poor connection with supervisors and coworkers). Under these conditions, such employees would be less engaged in eco-friendly behaviors. Fourth, our paper contributes to the better understanding of the factors influencing hotel employees’ met expectations and met expectations affecting their proactive PEBs. This is a critically important contribution since there is no established research illustrating the aforesaid linkages.

On a broader level, the findings of this study portray how job insecurity may prevent employees’ participation in organizational greening programs. Understanding this mechanism provides several useful insights for managers in hospitality and tourism in the global context where the security of jobs is not evitable among employees. More specifically, such employees feel exhausted from their unmet expectations in the workplace. Therefore, all the practices that may mitigate employees’ emotional exhaustion and decrease the level of their unmet expectations can be so helpful in motivating them to engage in organizationally desirable behaviors. To achieve that, management can use techniques such as appreciation of employees’ green behaviors either in financial or non-financial ways. The appreciation which can be in sort of certification allocation, small remuneration during monthly payments, and verbal supervisory support can all help them to be less exhausted and meet a considerable amount of their demands. In addition, during the recruiting interviews, managers can explain clearly the workplace conditions and the existence of likely deficits in fulfilling long-term employees’ job security demands. With this message, employees can adjust their expectations from employers and this may prevent future misunderstanding and unmet expectations among them.

The following implications would also be helpful. First, employees who experience JIS would have unmet expectations. These unmet expectations could be in the form of poor supervision, the kind and amount of work, poor connection with coworkers, unsatisfactory financial aspects (e.g., pay), and/or insufficient physical conditions [86]. Therefore, hotel companies should provide their employees with employment stability in return for their effective task performance based on organizational expectations. This is important because employees who perceive that management appreciates the work done and provides job security to the ones with good task performance would display positive outcomes such as proactive PEBs. Otherwise, successful employees would be beset with the threat of job loss in the organization in the future.

Second, management should create an environment where employees could take advantage of mentors to cope with emotional exhaustion. Since customer-contact employees are prone to elevated levels of emotional exhaustion due to stressors such as JIS [14], mentors who could ensure psychosocial support would enable employees to reduce their emotional exhaustion [99]. Third, management of hotels should organize training programs to share the company’s environmental sustainability efforts with employees. In these training programs, asking employees to exhibit eco-friendly behaviors and going beyond traditional duties associated with the environmental sustainability efforts of the company would enable management to achieve the environmental goals.

Fourth, if possible, hiring the individuals with strong environmental concern and the ones who are pro-environmentalists is one of keys to the accomplishment of the environmental goals [4]. To find out whether the candidates have harmonious passion for the environment, management can utilize experiential exercises or mini-case studies. Having strict selection criteria in place is critically important for this process.

5.4 Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Our research has several limitations that highlight the need for important future research directions. First, our study focuses on the hotel industry in a single country. Replication studies in the same setting in the same country and/or gathering cross-national data in other service settings and countries would enhance the database regarding the factors influencing employees’ proactive PEBs. Second, in the present paper, we measured only quantitative JIS. However, employees are also beset with qualitative JIS [35,36]. Therefore, assessing the effects of quantitative and qualitative JIS simultaneously on emotional exhaustion, met expectations, and proactive PEB would be an important contribution to the current knowledge base.

Third, the opportunities for research in hospitality and tourism settings on employees’ PEBs are very promising. However, the overwhelming majority of the empirical pieces have related green- or environmental-related issues to PEBs. Therefore, in future studies testing the effects of non-green or non-environmental factors (for example, workplace ostracism, job embeddedness) on PEB would add to the extant literature. Fourth, personality variables such as psychological capital would reduce employees’ perceptions of JIS and weaken their emotional exhaustion. Using psychological capital as a moderator of the detrimental effect of JIS on emotional exhaustion and proactive PEB would increase the existing knowledge [cf. 100]. Lastly, a qualitative follow-up would strengthen the conclusions and implications we draw from the quantitative analysis. This seems to be important for a depth of analysis concerning employees’ JIS and emotional exhaustion. Hence, utilizing a mixed-methods approach in future studies would be a potential solution.

Our paper addressed the less investigated factors influencing hospitality employees’ proactive PEBs, with implications on environmental sustainability and green initiatives of the companies. We showed that the serial mediation model we proposed was viable. Specifically, job-insecure employees were faced with elevated levels of emotional exhaustion and therefore displayed low levels of engagement in proactive PEBs. This was also true for employees whose expectations were not met. That is, employees reported reduced proactive PEBs as a result of heightened JIS and unmet expectations. More importantly, employees suffering from JIS at high levels were emotionally exhausted at levels and therefore found that their expectations were not met. Under these conditions, their involvement in proactive PEBs became low.

In a market environment where there is stiffening competition, investment in the development of employees’ green knowledge and skills to attain the environmental goals is a must for achieving differentiation and competitive advantage. With this realization, a richer understanding of factors affecting employees’ proactive PEBs will be continue to be significant since environmental problems and climate change are threats to nature [101]. It is hoped that the results of the present paper will inspire other researchers to focus on other less examined factors (e.g., the dark side of leadership) [102] that would influence proactive PEBs in a serial or triple-mediation model.

Acknowledgement: Data used in this study came from part of a larger project. Data collection for this project was carried out while the second author was a Visiting Researcher at the Guangdong University of Technology in China. We thank Professor Zhi Li (Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Computer Integrated Manufacturing System, School of Electromechanical Engineering, Guangdong University of Technology) for his kind assistance in enabling the second author to contact management of hotels. We also thank Ms. Liu Siai in the School of Foreign Languages and Mr. Zonggui Tian in the School of Electro-Mechanical Engineering (both at the Guangdong University of Technology in China) for their assistance in data collection.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Karatepe, T., Ozturen, A., Karatepe, O. M., Uner, M. M., Kim, T. T. (2022). Management commitment to the ecological environment, green work engagement and their effects on hotel employees’ green work outcomes. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(8), 3084–3112. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-10-2021-1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kim, M., Lee, S. M. (2022). Drivers and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(5), 1854–1881. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2021-1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bissing-Olson, M. J., Iyer, A., Fielding, K. S., Zacher, H. (2013). Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 156–175. DOI 10.1002/job.1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Karatepe, T. (2022). Do qualitative and quantitative job insecurity influence hotel employees’ green work outcomes? Sustainability, 14(12), 7235. DOI 10.3390/su14127235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Greenhalgh, L., Rosenblatt, Z. (1984). Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Academy of Management Review, 9(3), 438–448. DOI 10.2307/258284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Akgunduz, Y., Eser, S. (2022). The effects of tourist incivility, job stress and job satisfaction on tourist guides’ vocational commitment. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 5(1), 186–204. DOI 10.1108/JHTI-07-2020-0137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Khawaja, K. F., Sarfraz, M., Rashid, M., Rashid, M. (2022). How is COVID-19 pandemic causing employee withdrawal behavior in the hospitality industry? An empirical investigation. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 5(3), 687–706. DOI 10.1108/JHTI-01-2021-0002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang, S., Tang, Y., Zhang, C., Pan, W., Liu, H. et al. (2019). Risk the change or change the risk? The nonlinear effect of job insecurity on task performance. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 21(2), 45–57. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2019.010744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Caliskan, N., Ozkoc, A. G. (2020). Organizational change and job insecurity: The moderating role of employability. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(12), 3971–3990. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-05-2020-0387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Nikolova, I., Stynen, D., van Collie, H., de Witte, H. (2022). Job insecurity and employee performance: Examining different types of performance, rating, sources and levels. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(5), 713–726. DOI 10.1080/1359432X.2021.2023499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Van Hooteegem, A., Sverke, M., de Witte, H. (2022). Does occupational self-efficacy mediate the relationships between job insecurity and work-related learning? A latent growth modeling approach. Work and Stress, 36(3), 229–250. DOI 10.1080/02678373.2021.1891585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rezapouraghdam, H., Karatepe, O. M. (2020). Applying health belief model to unveil employees’ workplace COVID-19 protective behaviors: Insights for the hospitality industry. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 22(4), 234–247. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2020.013214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Khan, A. K., Khalid, M., Abbas, N., Khalid, S. (2022). COVID-19-related job insecurity and employees’ behavioral outcomes: Mediating role of emotional exhaustion and moderating role of symmetrical internal communication. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(7), 2496–2515. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-05-2021-0639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jung, H. S., Jung, Y. S., Yoon, H. H. (2021). COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102703. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cordes, C. L., Dougherty, T. W. (1993). A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 621–656. DOI 10.2307/258593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhu, X., Chu, T., Yu, Q., Li, J., Zhang, X. et al. (2021). Effectiveness of mind-body exercise on burnout and stress in female undergraduate students. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 23(3), 353–360. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.016339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang, Z., Wan, M., Wang, H., Wei, Y. (2018). Hidden dangers of identity switching: The influence of work-family status consistency on emotional exhaustion and workplace deviance. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 20(1), 1–13. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2018.010732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Amissah, E. F., Blankson-Stiles-Ocran, S., Mensah, I. (2021). Emotional labor, emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction in the hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights. DOI 10.1108/JHTI-10-2020-0196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Konkel, M., Heffernan, M. (2021). Hob job insecurity affects emotional exhaustion? A study of job insecurity rumination and psychological capital during COVID-19. Irish Journal of Management, 40(2), 86–99. DOI 10.2478/ijm-2021-0009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M. (1973). Organizational, work, and personal factors in employee turnover and absenteeism. Psychological Bulletin, 80, 151–176. DOI 10.1037/h0034829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Babakus, E., Cravens, D. W., Johnston, M., Moncrief, W. C. (1996). Examining the role of organizational variables in the salesperson job satisfaction model. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 16(3), 33–46. [Google Scholar]

22. Turnley, W. H., Feldman, D. C. (2000). Re-examining the effects of psychological contract violations: Unmet expectations and job dissatisfaction as mediators. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 25–42. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jiang, L., Lavaysse, L. M. (2018). Cognitive and affective job insecurity: A meta-analysis and a primary study. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2307–2342. DOI 10.1177/0149206318773853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(3), 242–264. DOI 10.1037/1076-8998.7.3.242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Safavi, H. P., Karatepe, O. M. (2019). The effect of job insecurity on employees’ job outcomes: The mediating role of job embeddedness. Journal of Management Development, 38(4), 288–297. DOI 10.1108/JMD-01-2018-0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Aguiar-Quintana, T., Nguyen, T. H. H., Araujo-Cabrera, Y., Sanabria-Díez, J. M. (2021). Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102868. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Koeske, G. F., Koeske, R. D. (1991). Student “burnout” as a mediator of the stress-outcome relationship. Research in Higher Education, 32(4), 415–431. DOI 10.1007/BF00992184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Morrison, E. W., Robinson, S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 226–256. DOI 10.2307/259230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Proost, K., van Ruysseveldt, J., van Dijke, M. (2012). Coping with unmet expectations: Learning opportunities as a buffer against emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21(1), 7–27. DOI 10.1080/1359432X.2010.526304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lee, R. T., Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A Meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 123–133. DOI 10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Raza, A., Farrukh, M., Iqbal, M. K., Farhan, M., Wu, Y. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior: The role of organizational pride and employee engagement. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28, 1104–1116. DOI 10.1002/csr.2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Shah, S. H. A., Cheema, S., Al-Ghazali, B., Ali, M., Rafiq, N. (2021). Perceived corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior: The role of organizational identification and coworker pro-environmental advocacy. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28, 366–377. DOI 10.1002/csr.2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tian, Q., Robertson, J. L. (2019). How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? Journal of Business Ethics, 155, 399–412. DOI 10.1007/s10551-017-3497-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zientara, P., Zamojska, A. (2018). Green organizational climates and employee pro-environmental behavior in the hotel industry. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(7), 1142–1159. DOI 10.1080/09669582.2016.1206554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hellgren, J., Sverke, M., Isaksson, K. (1999). A Two-dimensional approach to job insecurity: Consequences for employee attitudes and well-being. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 179–195. DOI 10.1080/135943299398311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hu, S., Jiang, L., Probst, T. M., Liu, M. (2021). The relationship between qualitative job insecurity and subjective well-being: The role of work-family conflict and work centrality. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 42(2), 203–225. DOI 10.1177/0143831X18759793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Park, J., Min, H(K) (2020). Turnover intention in the hospitality industry: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102599. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Liao, G., Wang, Q., Li, Y. (2022). Effect of positive workplace gossip on employee silence: Psychological safety as mediator and promotion-focused as moderator. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 24(2), 237–249. DOI 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.017610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang, Z., Xie, Y. (2020). Authentic leadership and employees’ emotional labor in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(2), 797–814. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-12-2018-0952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen, H., Eyoun, K. (2021). Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102850. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Shin, Y., Lee, E. J., Hur, W. M. (2022). Supervisor incivility, job insecurity, and service performance among flight attendants: The buffering role of coworker support. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(6), 901–918. DOI 10.1080/13683500.2021.1905618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Altinay, L., Dai, Y. D., Chang, J., Lee, C. H., Zhuang, W. L. et al. (2019). How to facilitate hotel employees’ work engagement: The roles of leader-member exchange, role overload and job security. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(3), 1525–1542. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-10-2017-0613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ugwu, F. O., Nwaosumba, V. C., Ibiam, O. E. (2021). Job insecurity and psychological well-being: The moderating roles of self-perceived employability and core self-evaluations. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(2), 153–158. DOI 10.1080/14330237.2021.1903166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Zhang, J., Wang, S., Wang, W., Shan, G., Guo, S. et al. (2020). Nurses’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: The mediating effect of presenteeism and the moderating effect of supervisor support. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2239. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mahmoud, A. B., Reisel, W. D., Fuxman, L., Hack-Polay, D. (2022). Locus of control as moderator of the effects of COVID-19 perceptions on job insecurity, psychosocial, organizational, and job outcomes for MNE region hospitality employees. European Management Review, 19, 313–332. DOI 10.1111/emre.12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Karatepe, O. M., Okumus, F., Saydam, M. B. (2022). Outcomes of job insecurity among hotel employees during COVID-19. International Hospitality Review. DOI 10.1108/IHR-11-2021-0070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Shah, S. H. A., Haider, A., Jiang, J. D., Mumtaz, A., Rafiq, N. (2022). The impact of job stress and state anger on turnover intention among nurses during COVID-19: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 810378. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.810378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Sahi, G. K., Roy, S. K., Singh, T. (2022). Fostering engagement among emotionally exhausted frontline employees in financial services sector. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 32(3), 400–431. DOI 10.1108/JSTP-08-2021-0175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Dogantekin, A., Secilmis, C., Karatepe, O. M. (2022). Qualitative job insecurity, emotional exhaustion and their effects on hotel employees’ job embeddedness: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 105, 103270. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Schumacher, D., Schreurs, B., van Emmerik, H., de Witte, H. (2015). Explaining the relation between job insecurity and employee outcomes during organizational change: A multiple group comparison. Human Resource Management, 55(5), 809–827. DOI 10.1002/hrm.21687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Ul Ain, N., Azeem, M. U., Sial, M. H., Arshad, M. A. (2022). Linking knowledge hiding to extra-role performance: The role of emotional exhaustion and political skills. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 20(3), 367–380. DOI 10.1080/14778238.2021.1876536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Said, H., Tanova, C. (2021). Workplace bullying in the hospitality industry: A hindrance to the employee mindfulness state and a source of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 96, 102961. DOI 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Vo-Thanh, T., Vu, T. V., Nguyen, N. P., Nguyen, D. V., Zaman, M. et al. (2022). COVID-19, frontline hotel employees’ perceived job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: Does trade union support matter? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(6), 1159–1176. DOI 10.1080/09669582.2021.1910829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Grant, K., Cravens, D. W., Low, G. S., Moncrief, W. C. (2001). The role of satisfaction with territory design on the motivation, attitudes, and work outcomes of salespeople. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(2), 165–178. DOI 10.1177/03079459994533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Naumann, E., Widmier, S. M., JacksonJr, D. W. (2000). Examining the relationship between work attitudes and propensity to leave among expatriate salespeople. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 20(4), 227–241. [Google Scholar]

56. Ababneh, K. I. (2020). Effects of met expectations, trust, job satisfaction, and commitment on faculty turnover intentions in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(2), 303–334. DOI 10.1080/09585192.2016.1255904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Rosing, F., Boer, D., Buengeler, C. (2022). Leader trait self-control and follower trust in high-reliability contexts: The mediating role of met expectations in firefighting. Group and Organization Management. DOI 10.1177/10596011221104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Bezdrob, M., Šunje, A. (2021). Transient nature of the employees’ job satisfaction: The case of the IT industry in Bosnia and Herzegovina. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 27, 100141. DOI 10.1016/j.iedeen.2020.100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Luu, T. T. (2019). Building employees’ organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The role of environmentally-specific servant leadership and a moderated mediation mechanism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(1), 406–426. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-07-2017-0425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Novacka, L., Pícha, K., Navratil, J., Topaloglu, C., Švec, R. (2019). Adopting environmentally friendly mechanisms in the hotel industry: A perspective of hotel managers in central and eastern european countries. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(6), 2488–2508. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-04-2018-0284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Pinzone, M., Guerci, M., Lettieri, E., Husingh, D. (2019). Effects of ‘green’ training on pro-environmental behaviors and job satisfaction: Evidence from the Italian healthcare sector. Journal of Cleaner Production, 226, 221–232. DOI 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Rezapouraghdam, H., Alipour, H., Darvishmotevali, M. (2018). Employee workplace spirituality and pro-environmental behavior in the hotel industry. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(5), 740–758. DOI 10.1080/09669582.2017.1409229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Ogretmenoğlu, M., Akova, O., Goktepe, S. (2022). The mediating effects of green organizational citizenship on the relationship between green transformational leadership and green creativity: Evidence from hotels. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 5(4), 734–751. DOI 10.1108/JHTI-07-2021-0166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Naz, S., Jamshed, S., Nisar, Q. A., Nasir, N. (2021). Green HRM, psychological green climate and pro-environmental behaviors: An efficacious drive towards environmental performance in China. Current Psychology. DOI 10.1007/s12144-021-01412-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Murtaza, S. A., Mahmood, A., Saleem, S., Ahmad, N., Sharif, M. S. et al. (2021). Proposing stewardship theory as an alternate to explain the relationship between CSR and employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability, 13, 8558. DOI 10.3390/su13158558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Lin, M. T., Zhu, D., Liu, C., Kim, P. B. (2022). A systematic review of empirical studies of pro-environmental behavior in hospitality and tourism contexts. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(11), 3982–4006. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-12-2021-1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50(3), 337–421. DOI 10.1111/1464-0597.00062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Shaffer, M. A., Harrison, D. A., Gilley, K. M., Luk, D. M. (2001). Struggling for balance amid turbulence on international assignments: Work-family conflict, support and commitment. Journal of Management, 27(1), 99–121. DOI 10.1177/014920630102700106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Qian, S., Yuan, Q., Niu, W., Liu, Z. (2022). Is job insecurity always bad? The moderating role of job embeddedness in the relationship between job insecurity and job performance. Journal of Management and Organization, 28, 956–972. DOI 10.1017/jmo.2018.77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Darvishmotevali, M., Arasli, H., Kilic, H. (2017). Effect of job insecurity on frontline employee’s performance: Looking through the lens of psychological strains and leverages. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(6), 1724–1744. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-12-2015-0683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Etehadi, B., Karatepe, O. M. (2019). The impact of job insecurity on critical hotel employee outcomes: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 28(6), 665–689. DOI 10.1080/19368623.2019.1556768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Koeske, G. F., Koeske, R. D. (1993). A preliminary test of a stress-train-outcome model for reconceptualizing the burnout phenomenon. Journal of Social Service Research, 17(3/4), 107–135. [Google Scholar]

73. Nauman, S., Zheng, C., Naseer, S. (2020). Job insecurity and work–family conflict: A moderated mediation model of perceived organizational justice, emotional exhaustion and work withdrawal. International Journal of Conflict Management, 31(5), 729–751. DOI 10.1108/IJCMA-09-2019-0159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Lazarus, R., Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

75. Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848. DOI 10.1037/a0019364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Hsieh, H., Karatepe, O. M. (2019). Outcomes of workplace ostracism among restaurant employees. Tourism Management Perspectives, 30, 129–137. DOI 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.02.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Jabutay, F. A., Suwandee, S., Jabutay, J. A. (2022). Testing the stress-strain-outcome model in Philippines-based call centers. Journal of Asia Business Studies. DOI 10.1108/JABS-06-2021-0240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Rosenblatt, Z., Ruvio, A. (1996). A test of a multidimensional model of job insecurity: The case of Israeli teachers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 587–605. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Houkes, I., Janssen, P. P. M., de Jonge, J., Bakker, A. B. (2003). Specific determinants of intrinsic work motivation, emotional exhaustion and turnover intention: A multisample longitudimnal study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76, 427–450. DOI 10.1348/096317903322591578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Judd, C. M., Smith, E. R., Kidder, L. H. (1991). Research methods in social relations, 6th ed. Fort Worth: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. [Google Scholar]

81. Bufquin, D. (2020). Coworkers, supervisors and frontline restaurant employees: Social judgments and the mediating effects of exhaustion and cynicism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 3(3), 353–369. DOI 10.1108/JHTI-11-2019-0123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. HairJr, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

83. Delery, J. E., Doty, D. H. (1996). Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 802–835. DOI 10.2307/256713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Babakus, E., Cravens, D. W., Jonhnston, M., Moncrief, W. C. (1999). The role of emotional exhaustion in sales force attitude and behavior relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(1), 58–70. DOI 10.1177/0092070399271005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Lee, T. W., Mowday, R. T. (1987). Voluntarily leaving an organization: An empirical investigation of steers and mowday’s model of turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 30(4), 721–743. DOI 10.2307/256157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Anderson, J. C., Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. DOI 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. DOI 10.1007/BF02723327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Fornell, C., Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. DOI 10.1177/002224378101800104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Joreskog, K., Sorbom, D. (1996). LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

91. Kaviti, R., Karatepe, O. M. (2022). Do personality variables predict job embeddedness and proclivity to be absent from work? International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 24(3), 331–345. DOI 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.018516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach, New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

93. Cho, M., Yoo, J. J. E. (2021). Customer pressure and restaurant employee green creative behavior: Serial mediation effects of restaurant ethical standards and employee green passion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(12), 4505–4525. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-06-2021-0697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Srivastava, S., Gupta, P. (2022). To speak or not to speak: Motivators for internal whistleblowing in hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(10), 3814–3833. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2021-1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Wan, Z., Huang, S., Choi, H. C. (2021). Modification and validation of the travel safety attitude scale (TSAS) in international tourism: A reflective-formative approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 5(5) DOI 10.1108/JHTI-01-2021-0012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Yoon, D. J., Muir, C. P., Yoon, M. H., Kim, E. (2022). Customer courtesy and service performance: The roles of self-efficacy and social context. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43, 1015–1037. DOI 10.1002/job.2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Xiao, J., Mao, J. Y., Quan, J. (2022). Flight attendants staying positive! The critical role of career orientation amid the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(11). DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-08-2021-0965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Chen, H., Qi, R. (2022). Restaurant frontline employees’ turnover intentions: Three-way interactions between job stress, fear of COVID-19, and resilience. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(7), 2535–2558. DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-08-2021-1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Lankau, M. J., Scandura, T. A. (2002). An investigation of personal learning in mentoring relationships: Content, antecedents, and consequences. Academy of Management Journal, 45(4), 779–790. DOI 10.2307/3069311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Kim, T., Karatepe, O. M., Lee, G., Lee, S., Hur, K. et al. (2017). Does hotel employees’ quality of work life mediate the effect of psychological capital on job outcomes? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(6), 1638–1657. [Google Scholar]

101. Rezapouraghdam, H., Karatepe, O. M., Enea, C. (2022). Sustainable recovery for people and the planet through spirituality-induced connectedness in the hospitality and tourism industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights. DOI 10.1108/JHTI-03-2022-0103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Mackey, J. D., Ellen III, B. P., McAllister, C. P., Alexander, K. C. (2021). The dark side of leadership: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of destructive leadership research. Journal of Business Research, 132, 705–718. DOI 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools