Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Exploring the Impact of Crisis and Trauma on the Mental Health and Psychological Well-Being of University Students in Northern Haiti

1 Harvard University, Cambridge, 02138, USA

2 Boston University, Boston, 02215, USA

3 Centre de Santé Mental de Morne Pelé, Cap-Haïtien, 2697, Haiti

4 Université Publique du Nord au Cap-Haïtien, Cap-Haïtien, 2697, Haiti

5 Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, 63130, USA

* Corresponding Author: Michael Galvin. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(2), 173-191. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.018800

Received 18 August 2022; Accepted 27 October 2022; Issue published 02 February 2023

Abstract

In recent decades, Haiti has been subject to man-made and natural disasters that have left its citizens vulnerable to a range of shocks. With a weak state unable to protect its populace, Haitians are exposed to some of the highest levels of poverty and violence in the Western Hemisphere. In recent years, Haitians have experienced two crises that this study analyzes: the instability and political violence of “peyi lòk” as well as the global pandemic of COVID-19. This community-based assessment explores the impact of these two crises on the mental health and psychological well-being of 38 Haitian university students in the understudied northern part of the country. Results indicate that both crises had similarities related to their psychological effects on young people, most notably in terms of traumatic experiences related to threats or violence, forced confinement, and large increases in population-wide uncertainty. Additionally, the extreme violence of “peyi lòk” and the widespread unpredictability of COVID-19 and its effects in the early days of the pandemic resulted in high levels of stress and fear. Both crises also resulted in extreme economic hardship for students, with many reporting difficulties accessing basic needs such as food and water. This study highlights how converging population-level crises in “complex emergencies” can heighten trauma and compromise mental health.Keywords

History of Recent Crises in Haiti

Over the last several decades, Haiti has experienced countless crises. These crises range from social, economic, health, political, legal, and environmental, and have impacted every level of Haitian society [1,2]. Yet, while undergoing many of these acute crises, Haiti is also experiencing a more chronic crisis similar to many other “fragile states” around the world. With a government that lacks the will and/or the capacity to manage public resources and deliver core state functions such as essential infrastructure, protection of property, basic public services, and security, the population is largely left to fend for itself in the face of mass poverty and collective violence [3].

Haiti currently has one of the lowest Human Development Index (HDI) ratings in the world at 0.498—on a scale of 0 to 1—ranking 168th out of 189 countries [4]. This compares with an average of 0.758 for the Latin American and Caribbean regions [5]. In his groundbreaking book, Haiti, An Economy of Violence: Political Instability and Economic Violence, Haitian economist Fritz Alphonse Jean describes an unequal system offering little opportunity to young people, where violence and civil disruption are the norms, and armed gangs are hired by warring parties in both the private and public sector [3]. He describes a country where 67% of the population continues to live on less than $2 a day, where electricity has never reached more than 30% of the population—only 5% in rural areas—and 80% of those with higher education choose emigration. Other studies confirm this, finding that 85% of Haitians with a diploma live outside the country [6].

Traditionally, disasters have been characterized as either “man-made” or “natural”—though they are not always mutually exclusive—and Haiti has experienced its share of natural disasters. In the last ten years, much has been written about the 2010 earthquake which killed an estimated 220,000 Haitians, injured another 300,000, and left more than a million homeless in a population of just 11 million [7,8]. Former Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide writes about how conditions in Haiti led to such a large death toll, as Mexico has had several earthquakes of higher magnitude near large urban areas with exponentially smaller death counts [9]. In addition to the earthquake, however, Haiti has also been hit by a total of 26 hurricanes since the year 2000 alone. In particular, the 2016 Hurricane Matthew devastated the southern part of the country, with an estimated 175,000 people displaced, leaving many facing food insecurity due to damage to crops and livestock. The country was simultaneously combatting the cholera epidemic which was introduced by United Nations peacekeepers following the 2010 earthquake [10].

Aside from natural disasters, Haiti is also confronted with serious “man-made” disasters, particularly in the form of socio-political crises. For example, since the fall of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986, Haiti has experienced 21 presidents in just 32 years with many of them coups d’états [11]. Due in part to this instability, compounded with structural and organizational weaknesses, Haiti has the lowest GDP in the hemisphere [2,4,12]. An estimated 70% of people living in Haiti are unemployed, and 80% of those who do have jobs work in the informal sector [13]. In one study on the relationship between political crises and economic growth, another Haitian scholar found that since the fall of the Duvaliers in 1986, political instability consistently had a negative impact on economic growth, as the economy plummeted with each political crisis [14]. This has left the country with one of the lowest standards of living in the hemisphere, with increasing population pressures and conflict over control of scarce resources.

Current Crises: Peyi Lòk and the COVID-19 Pandemic

The two crises examined for the purposes of this study were the recent political crisis and lockdown of 2019 referred to locally as peyi lòk—or “locked country”—in Haitian Creole (Krèyol). Slowing in early 2020, this crisis was quickly followed by the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic and the government-imposed national lockdown in Haiti in March 2020.

The origins of the political and social crisis called peyi lòk started following the 2010 earthquake when Haitians elected popular singer Michel Martelly to the presidency in 2011. In 2016, his hand-picked successor Jovenel Moïse was elected after a contested election. In 2017, a probe by the Superior Court of Auditors found that nearly $3 billion of Venezuelan loans through the Petrocaribe program had been embezzled by these two governments, with president Moïse himself receiving millions of dollars in fake contracts [15]. In response, the political opposition staged protests against rampant government corruption. While protests were scattered through 2018, they were often violent, occasionally forcing people to remain at home, as roads were blocked and schools closed [16].

However, protests increased significantly in 2019 leading Haiti into a period of lockdown referred to as peyi lòk. The country was brought to a standstill for months at a time. These protests culminated in the second half of 2019 with protesters forcing the extended shutdown of roads connecting all regions of the country as well as virtually all of the country’s primary institutions. In this extended period of social and political unrest, many were unable to access sufficient food, water, or medical care for significant periods of time. According to one estimate, 40% of Haitians were in need of emergency food assistance by the end of 2019 [4]. In addition, gangs proliferated throughout the country causing widespread violence as the government lost control of large swaths of the country. Reported incidents of unrest, extreme violence, and kidnapping rose significantly during this period [17]. Peyi lòk finally began to ease in December of 2019, though scattered protests continued.

The COVID-19 pandemic followed quickly with reports of cases in China in late 2019. Global alarm increased after a sharp rise in cases in Northern Italy in February 2020, from which the virus quickly spread to the rest of Western Europe and the Americas [4]. After the first two cases were confirmed in Haiti on March 19th, the president declared a state of emergency [18]. New measures were announced on March 22nd, closing schools and universities, shutting down manufacturing industries, prohibiting public gatherings of more than 10 people, implementing a daily curfew from 8 pm to 5 am, and closing all land, air, and sea ports transporting human beings [19,20]. Once again the country was brought to a standstill for months as Haitians waited to see how the virus would impact them.

As millions of Haitians make a living day to day, many were unsure how they would make ends meet, as larger urban areas closed public markets and banned unnecessary movement [4]. While cases continued to increase—albeit slower than in other parts of the world—the Prime Minister reopened some businesses such as textile factories on April 20th [21]. Confirmed cases rose through the Spring and culminated on June 6th with 332 cases on that day [22]. Following June 6th however recorded cases slowly declined to remain in the double and single digits for the remainder of 2020. On July 1st, the country decided to reopen flights in and out of the country and reduced the hours of the curfew from midnight to 4 am daily [23]. Despite alarm on the part of international officials, with the director of the Pan American Health Organization stating in May that Haiti had “a perfect storm approaching” with regards to the threat of COVID-19 in the country, only 233 deaths due to the virus had been confirmed in Haiti as of December 2020—though cases and deaths were likely underreported due to limitations in surveillance capabilities [22,24].

Crisis, Trauma, and Youth Mental Health

Many studies have demonstrated a strong association between traumatic events and decreased psychological well-being [25–27]. These events can have significant impacts on mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and stress [28]. Significant literature has emerged in recent years about the relationship between trauma and mental health in the context of “complex emergencies”—or situations characterized by multiple crises such as extreme violence, poverty, environmental disasters, or the breakdown of established infrastructure [29–31]. In essence, these “complex emergencies”—or multi-layered society-level crises—not only cause increased hardship for populations, but also lead to increased rates of population- and individual-level trauma and decreased capacity to provide for people in need of psychosocial support or care [32–34].

In the context of high levels of extreme violence as well as severe political and social unrest in Haiti in recent years, research has found elevated levels of trauma-related disorders [35]. Several studies have examined the role of socio-political violence and unrest during periods of crisis in Haiti [36–38]. As the average age in Haiti is only 24, many of these studies focus on the experiences of youth, who make up a larger percentage of the population than in any other country in the hemisphere [39]. In particular, one study found that nearly 40% of Haitian youth have experienced traumatic events such as kidnapping, gang violence, or physical/sexual assault, with rates of such incidents increasing significantly during periods of social unrest or society-level crises [40]. Another comprehensive study in Port-au-Prince sampled 1,260 households looking at experiences of violence following the political unrest after the 2004 overthrow of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The authors find stark impacts with an estimated 8,000 murders and 35,000 rapes—with more than half of victims under 18 years old—during the 22-month assessment period [41]. While this research examined Haiti through the lens of crisis, few have examined the impact of these crises on mental health and psychological well-being of youth in the country. The remaining studies which do focus on mental health and crisis in Haiti examine it in the context of the 2010 earthquake [42–44]. One of the most exhaustive of these studies is entitled Narratives in Sensitivity: Post-Traumatic Stories from Survivors of the January 12th, 2010 Earthquake in Haiti [45]. In this work, Haitian psychologist Jeff Matherson Cadichon examines the impact that this natural disaster and crisis had on the mental health of youth survivors, reporting more than 35% of young people interviewed continue to have severe post-traumatic symptoms years after the earthquake.

While much of this research has taken place in and around the capital, Port-au-Prince, only one study examining the relationship between crisis, trauma, and mental health looked at the north of the country [46]. This study also examined experiences and perceptions of violence following the departure of Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004. During this period, the city of Cap-Haïtien was attacked and overrun, the airport was looted, and parts of the city were ransacked and burned to the ground [46]. The authors described organized violence as chronic and pervasive in Haiti due to coups d’états, civil unrest, extreme poverty, and lack of infrastructure. To determine the relationship between this crisis and mental health, the study interviewed populations in slum areas of Cap-Haïtien as well as nearby towns through key-informant interviews. The authors found a strong relationship between periods of crisis and symptoms of mental distress, making the case for the development of effective interventions to treat sufferers as well as the need for increased capacity to deal with large-scale crises in the region.

In order to develop programs for mental health and psychosocial support, it is important to know what people who live in these settings see as the most pressing problems, and where problems related to mental health and psychological well-being are situated in relation to all of the difficulties people are facing. Assessments that use methods derived from qualitative social sciences are based on what people report themselves, providing useful measures of the saliency of local conceptualizations of mental health and well-being and their importance in specific contexts [47]. The overall goal of this study is to assess the impact of current crises on the mental health of youth by examining a sample of university students. In terms of specific objectives, this research seeks to understand the perceived causes of these crises by youth, to characterize the impact of these crises on students’ lives and lived experiences, and to describe youth perception of impacts on Haitian society as a whole.

This study describes a community-based assessment with focus groups of Haitian public health university students in Cap-Haïtien, Haiti. Cap-Haïtien is the second largest city in Haiti with a population of roughly 500,000 inhabitants. Using qualitative methods, this study consisted of six focus group discussions which were conducted between September and November of 2020 at the Université Publique du Nord au Cap-Haitïen (UPNCH). A population of university students at UPNCH was selected for this study due to an ongoing educational partnership between the department of Washington University in St. Louis and UPNCH since 2017. As one of the largest public universities in northern Haiti, UPNCH started its bachelor’s degree program in Public Health and Social Work in 2017 with the support of Washington University in St. Louis to increase expertise in these domains, as well as to train future public health and social work leaders for the country [48]. In order to enter the program, students take a competitive exam and are selected for entrance based on their scores. Public health university students were determined to be an ideal group for conducting this research as they are more likely to be educated about and aware of the political and public health implications of crises such as peyi lòk and the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to being affected in their personal lives.

Participants were selected through a convenience sampling process in which all students in the program were offered the opportunity to participate. Inclusion criteria for participation consisted of students currently attending the Public Health and Social Work bachelor’s degree program at UPNCH, students who were present in Haiti for the entirety of the crises, and agreed to informed consent. The six focus groups were composed of between five and eight students and lasted for 45 minutes to one hour. All participants were aged between 18 and 24 years old and all focus groups were a mixture of male and female students, with 38 students interviewed in total—18 male and 20 female. Fourteen students were in the fourth year of the program and 24 students were in the second year of the program. As UNPCH is a public university with low fees for attendance, students interviewed were largely from modest socio-economic backgrounds. Other studies reported that at least 20 interviewees representing both genders were needed to identify salient issues, therefore this study nearly doubled that number to ensure saturation was achieved [46].

Students were provided a small lunch as compensation for their participation in the study. While they ate, students were explained the purpose of the study, examining the relationship between current crises and mental health in Haiti, and asked if they were interested in participating. After confirming interest, they were then presented with a form explaining the study, and informed consent was obtained. Students were informed that they did not have to speak about any information that they did not feel comfortable sharing. However, they were encouraged to share both the experiences of themselves and their families as well as their perception of the effects on society in general. Once the audio recording was begun, students were first asked, “What is your perception of the relationship between peyi lòk and mental health in Haiti based on your experiences?” After each student had the chance to speak, students were then asked, “What is your perception of the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health in Haiti based on your experiences?” Once again all students had a chance to speak. When they were finished students were asked, “Which crisis had a more serious impact on mental health in Haiti based on your experience?” A Haitian research assistant guided each discussion, asked probing questions when more information was needed regarding a student’s account and took notes on the discussion.

All focus group interviews were conducted in Krèyol. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Original transcripts in Krèyol were coded by both the PI and research assistant using NVivo software and analyzed through an inductive process. An inductive approach was chosen over a deductive approach as researchers wanted to develop research themes solely based on the data collected, rather than having pre-conceived themes that would then be applied to participant observations. The analysis consisted of both researchers developing a list of codes independently, then comparing codes to ensure agreement. The codes were reviewed and discussed, modified if needed, and agreed upon by both the PI and research assistant at UPNCH. Codes were then consolidated into a single summary list of problems and symptoms, then ranked based on how many respondents reported each item. Researchers determined that while the number of times a given item was reported does not necessarily imply greater resonance, in this particular research the frequency of mentions had a strong correlation to the importance of different concepts overall. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained for this study from Washington University in St. Louis (IRB #202005009), and the Haiti National IRB—or Comité National de Bioéthique (IRB #1920-51).

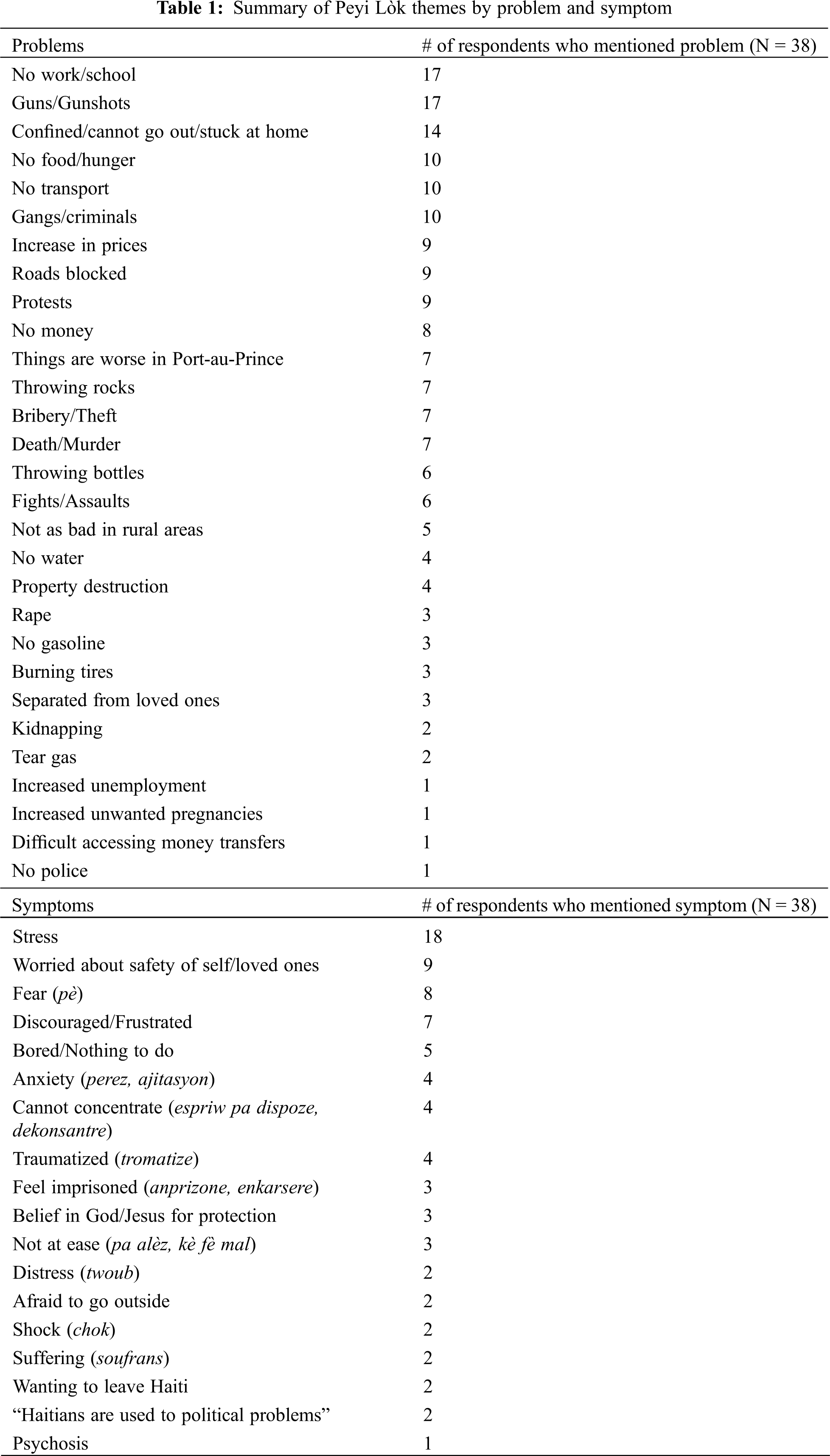

Several major themes emerged from the focus group discussions on peyi lòk (Table 1). The primary causes of psychological problems were related to the protests and violence, and the shutdown of normal life that resulted in late 2019. Students were unable to work or go to school for months at a time, a fact mentioned by 17 of 38 students. Fourteen students described being confined, stuck at home, or unable to go outside due to the crisis. “All productivity was at a standstill (pwodiktivite a li kanpe net),” one student remarked. With many unable to work or go to school, students also described a steep decline in their economic situation while simultaneously recounting a significant rise in prices—mentioned by 9 students—for many necessities.

As the crisis continued for months, students described an inability to meet basic needs such as finding food and water. With less money and the inability to work, several students stated there was a lack of food and widespread hunger in their homes and communities. Ten students described not having enough food or experiencing hunger, and 8 discussed a lack of money. One student said he felt the “hunger in the body” (grangou nan kòw). Another was unable to find water for an extended period:

“A lot of people couldn’t find food during this period, other times it was hard to find water or you had to go out for water even though the neighborhood was really dangerous” (zòn nan toujou cho).

Others mentioned how even when they could find potable water, the price tripled going from 60-70 gourdes ($1) to 175 gourdes ($3). “Even if you have money, you might not have food or anything to drink since you can’t go outside [to buy anything]” one said. Another remarked that “you can only go out for provisions on certain days, Friday and Saturday usually because on Monday the craziness (tenten) would start again.” Two students described how market sellers were often unable to come into the city with their products, so there was nothing to buy even for those with money.

Widespread violence was another common theme in focus groups. Seventeen students mentioned guns or gunshots which highlighted the level of danger in the streets. Others discussed the use of rocks and bottles as weapons by gangs and protesters, with 7 and 6 mentions, respectively. The primary culprits in this violence were gangs which were cited by 10 students. As one described, in many neighborhoods,

“The gangs have power over life and death…you have to wait until they let you leave your house, and then also when you want to go back home again.”

Similar to other countries, gangs in Haiti are primarily made up of young men from poor backgrounds and have increased significantly in urban areas in recent years [4]. During peyi lòk, students described how gangs would block roads—including the one bridge that connects the two halves of the city—and force people to pay to pass: “when you cross the bridge [which connects the city], whether you’re in a private car or public transport, you have to pay them [the gangs] a bribe.” In addition, theft was common and impunity was rife. “Gangsters (bandi) would stand around, frisk everyone who walked by and take everything they had on them,” in one student’s neighborhood.

Brutality increased as the crisis went on, with battles breaking out between different neighborhoods in the city center. Two poor neighborhoods in particular, Shada and Nan Bannann were overrun with gangs that “took advantage of the situation to terrorize the population.” Several students reported seeing killings with their own eyes. One student remarked,

“At one point there were 3 people who were burned alive in the city near my house, and that really affected me. I asked myself, how would a human burn another human to death like that?”

Another reflected on the particular risks for young women among the violence: “[the gangs blocking the roads] would steal people’s cars and take the young girls and rape them in the middle of the road or out in the forest” (fè aksyon sou fiy yo nan mitan wout la ou nan raje).

While several students were in Port-au-Prince during this period and reported even more severe violence and unrest than in Cap-Haïtien—describing “total insecurity” and being unable to sleep due to the gunshots—the violence in Cap-Haïtien still stood in stark contrast to the relative calm of the countryside. Four students described leaving the cities to live in the countryside during this period, in order to escape the violence and unrest. “During peyi lòk I had to return to the countryside, it was getting too hard to go outside in the city and buy things,” one said. Another remarked that while schools and places of business were still closed in the cities, they were open in the countryside, allowing people to resume some normal activities there.

Among psychological problems, the most salient theme discussed was stress which was mentioned by 18 of the 38 students. One student described peyi lòk as a whole as “just a period of intense stress.” After stress, 9 students mentioned worrying about the safety of themselves and their loved ones. One student described how,

“During peyi lòk there were a lot of people who were victims; if it’s not from a rock someone threw, it can be from hunger or thirst, a medication, or just stress. You always ask yourself, if I go out will they throw rocks at me? Will there be gasoline [for transportation]? Will there be people burning tires?”

Fear (pè), feeling discouraged or frustrated, and boredom followed closely behind—with 8, 7, and 5 mentions, respectively. Four students said they were traumatized (tromatize). Three students described peyi lòk as being like a prison (amprizone). Students told stories about being afraid to go out as they were often unable to return home due to protests or violence, forcing them to walk for miles or take long detours. Others reported that even when they tried to get work done, they could not concentrate:

“I couldn’t come to school, and I wasn’t able to concentrate on anything [at home]. This means that every time you’re trying to think about something, the only thing you can think about is what’s going on in the country.”

Three students stated religious beliefs and God (Bondye) helped them make it through this period, with 2 expressing a desire to leave the country.

Peyi lòk was therefore first and foremost characterized by extreme violence and economic hardship. These factors resulted in widespread hunger, stress, and fear in the population at large as people could no longer work or go to school, and often feared simply going out in search of basic necessities. By December 2020, peyi lòk began to ease. Markets reopened, roads were no longer blocked, and travel between large cities recommenced throughout the country. However, this opening would only last for a few months before the government imposed a lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

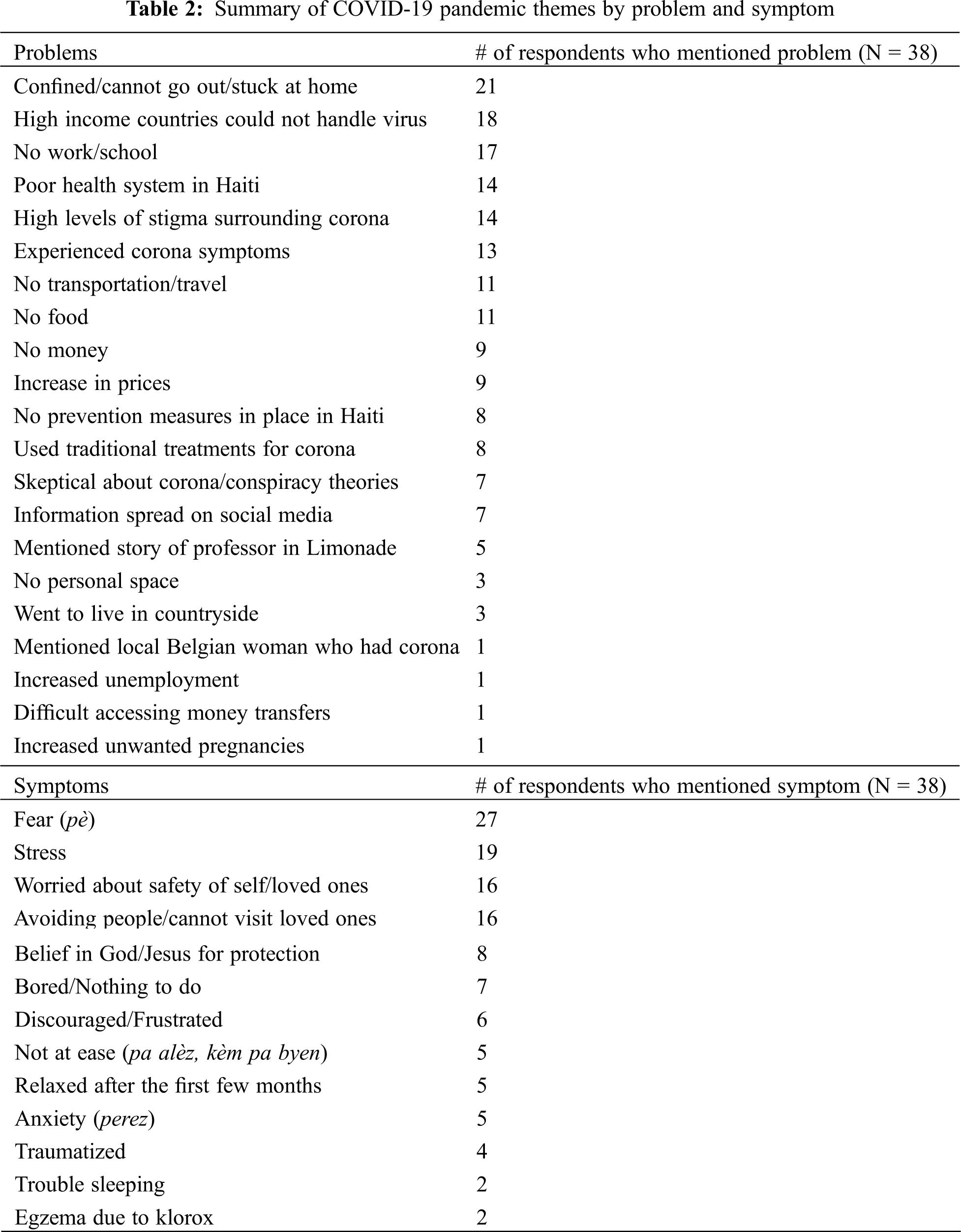

Some similar themes were raised with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown when compared with peyi lòk. Twenty-one of 38 students cited confinement or being unable to leave home or go outside again in 2020 (Table 2). One student described the lockdown as “peyi lòk’s little brother (piti frè peyi lòk)” and another called it “global peyi lòk,” reflecting on how the whole world was now shut down like Haiti was in 2019. However, unlike peyi lòk, the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown did not result in large-scale violence. Rather students primarily expressed concern about the impact of the virus itself, as well as the economic repercussions of the lockdown.

In the initial months of the pandemic, 18 students cited concern about the fact that high-income countries were unable to handle the influx of patients resulting in significant deaths. “After what happened in France and Italy, I thought it was possible that all Haitians might die of corona if it entered the country,” one student said. Another remarked, “if it [COVID-19] got to Haiti we would die in droves.” These comments highlight the widespread uncertainty in this early period and the fear that COVID-19 could have an even more serious impact in Haiti than in more developed countries.

“When you saw the big countries had people dying, we were worried because Haiti doesn’t really have a health system or good hospitals,” another added.

The poor state of the healthcare system was mentioned by 14 students. In a country where 50% of medical services are provided by NGOs, students noted how Haiti’s medical system does not allow easy access to care, also highlighting the fact that many doctors and nurses were not coming to work in the early weeks of the pandemic out of fear of the virus and due to a dearth of appropriate protective equipment. As participants were all students of public health, their training provided them with extensive knowledge of Haiti’s healthcare system and its weaknesses.

In addition to the lack of appropriate medical services and infrastructure in Haiti, 8 students noted the absence of prevention measures for COVID-19 among the population. One student remarked how “Haiti wasn’t prepared to respond to a pandemic” while another said that “there weren’t good measures in place, and Haitians were negligent in that lots of people didn’t wear masks.” Speaking about his low-income neighborhood near the city center, Baryè Boutey, one student remarked that “out of 100 people, 95 will tell you they won’t wear a mask.” Part of this was related to the unique way stigma developed regarding COVID-19 during the early days of the pandemic and lockdown in Haiti. Fourteen students mentioned stigma as a significant problem during this period. With regards to masks, 3 students described how wearing a mask would make people think they had COVID-19. “If you wore a mask sometimes people would threaten you, they thought you had corona; so people didn’t really wear masks too much,” one described. Fears of threats or violence if you were suspected of having COVID-19 were a particular problem in the early months, according to 6 students. One said,

“There are people that can attack you if they think you represent a danger for them or those around them. They don’t need to know if you have it or not, they will just kill you so you don’t spread the illness (yo ta plis bezwen eliminew pouw pa pwopaje maladi a).”

As 13 students interviewed described having or fearing they had symptoms in the early months of the pandemic, there was considerable fear of both the virus and the stigma.

Several students described threats of violence with regard to fears of COVID-19 infection in the community. One student recounted an instance where someone was suspected of being infected and a group of men with machetes showed up at the house. Another student explained how one of his professors would kick students out of class for a small cough. In one final example, a student had to leave town due to threats from neighbors based on the perception he had been infected and could spread it to them. Perhaps the best illustration of the threats of violence related to COVID-19 stigma, however, was the case of a professor from the State University in the nearby town of Limonade who returned to Haiti on March 9th after a trip to the United States. On March 17th, he taught his classes at the university and came down with a fever and back pain [4]. He was immediately suspected of having COVID-19 and was contacted by the Ministry of Health to be tested. Yet, due to the lack of information on the virus at that time, locals threatened to burn his house down, he was threatened with death by armed groups and was refused care at the local hospital by worried doctors and nurses. Five students described this as a key incident with regard to the stigma of COVID-19, with one student interviewed saying he was present in the professor’s class the morning he fell ill. As that student describes,

“I had a class with him that Monday from 1–4 pm… when students started sharing information about the professor maybe having corona, the school was in upheaval, everyone ran home as fast as they could…I locked myself in my room and told my family to leave my food on the table without telling them anything [about what had happened].”

These experiences led to the professor’s ambulance being attacked when he was finally on his way to the hospital, almost killing him.

Part of the difficulty in a crisis like COVID-19 in the era of pervasive social media use in settings with low levels of education is the rapid spread of false information. Students reported receiving information via WhatsApp in the month of March that predicted 150,000 Haitians to die from COVID-19, with another saying that 1,000 to 2,000 people were expected to die in the country per day by May. Other false information widely shared on social media included “little hair tea” (te ti plim) which was mentioned by 2 students. As one described,

“When you open the Bible you’re supposed to look for a hair in the pages, and when you find one you boil it with water and put it in a kettle. The whole family drinks it and that prevents everyone from getting corona. All Haitians heard about this. If you believe in God, people would say only God can help us now, and this is the solution… Everyone was buying Bibles and searching in the pages, it was like a game.”

While the origins of this social media phenomenon are unclear, the rumor is reported to have been started by a pastor in Ghana where it quickly spread [49].

The uncertain nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown led 8 students to express a belief in God or Jesus for protection. Coupled with a fear of hospitals, many Haitians turned to traditional treatments to either prevent or treat COVID-19. Eight students discussed using these remedies. In addition to the 2 that mentioned “little hair tea,” 5 mentioned using leaves for tea, 4 using ginger, 2 using rum, and 1 using aloe. With the surge in demand for many of these items, students described large rises in prices, with one student traveling to the countryside solely to purchase affordable ginger. As the border with the Dominican Republic remained shut due to the pandemic for the rest of 2020, many other prices went up as well as Haiti imports a significant percentage of its goods from its neighbor. Nine students mentioned the problem of an increase in prices, 9 described not having enough money, and 11 not enough food. As one student said, “there was a sort of famine [in this period], some families couldn’t eat… everyone just ate what they had.” With many Haitians living day to day, one student noted how “people [were] more afraid of hunger than corona.” With markets closed most days of the week, many necessities harder to find, and large numbers of people unable to work, the pandemic lockdown resulted in a significant hardship.

“My mom works in the market and my dad works in construction, so when all activities stopped we fell into extreme poverty. It was really hard the way we had to live,” another student said.

Despite the early months of uncertainty around the virus, the wave of deaths experienced in other parts of the world did not flood Haiti’s hospitals. Seven students mentioned the widespread presence of skepticism and conspiracy theories in the country with regard to the virus. Two cited the widespread belief that Haiti was too hot for COVID-19 to survive there. Another 2 discussed the conspiracy theory that the Haitian government invented the crisis to get money from international donors. “Haitians thought the government was trying to get aid money from other countries,” one student said. An additional 3 students described how poor Haitians thought it was just a disease for the wealthy: “people in the lower classes said it’s a disease for the bourgeois, and that they won’t get it.” A final student described the class divide in terms of education, saying,

“People who are educated were more stressed than people who are illiterate; they thought corona was nothing saying, ‘this disease isn’t for Haitians.’”

By October, a large banner appeared over the main road in town stating, “Thank you God for the protection you give us, you protected the country of Haiti against COVID-19 and especially the city of Cap-Haïtien.” This emphasized the widely believed notion that God had protected Haiti from the COVID-19 pandemic.

In terms of psychological problems, the most salient theme was fear (pè) mentioned by 27 out of 38 students. With the combination of factors discussed in the preceding paragraphs, one student described the early weeks of the lockdown as a “climate of fear.” Another student described how “lots of videos were being shared on social media about how the virus is spread… I was so afraid, I thought I had symptoms when I got home and was very anxious.” Next, 19 students described experiencing stress. One student reported how,

“It was so stressful because Haitians are used to living very close to one another, things are dirty, eating wherever, everything at the market is on the ground, not washing hands, dust everywhere,” fearing that these lack of precautions would lead to a more serious outbreak.

Following this, 16 students discussed worrying about the safety of themselves and their loved ones, with students with parents who worked at the hospital particularly concerned. Sixteen students also described avoiding people or being unable to visit loved ones due to the lockdown and/or concerns about the virus. Due to living in close quarters, social distancing was difficult for many: “In the area where I live you can’t go outside without being in close contact with so many other people. We couldn’t know if they were sick,” one student said. Seven students complained of boredom, 6 said they were discouraged or frustrated, 5 said they were not at ease (pa alèz), with an additional 5 expressing anxiety (perez). Four students said they were traumatized (tromatize). One student said during the pandemic lockdown, “I felt panicked, mentally I wasn’t functioning well.” Another said, “sometimes you’re so angry and you don’t even know why.” However, when the country started opening up again in the late Spring, 5 students mentioned the atmosphere relaxing significantly.

“After a few months I saw it wasn’t so bad in Haiti, I became more relaxed, and even started going out with a mask. It doesn’t really have an effect on me now,” one remarked.

Another said, “I got used to it, in any case, everything is open now in the country. I have the impression that we’re living like corona doesn’t exist for us here in Haiti.”

The COVID-19 pandemic in Haiti was therefore characterized by the government lockdown which forced people to stay at home, as well as the economic hardship that followed. Additionally, the pandemic provoked high levels of fear, stress, and uncertainty, as Haitians saw a new and menacing virus that was thrashing the most advanced healthcare systems in the world before it arrived on their shores. In combination with structural weaknesses in the country’s government and healthcare system, misinformation and stigma spread widely occasionally resulting in acts of violence.

3.3 Comparison of Peyi Lòk and the COVID-19 Pandemic

When asked which crisis had a more significant impact on mental health in Haiti, 21 students said peyi lòk whereas 16 students said the COVID-19 pandemic, with 1 student undecided. In their justifications for selecting peyi lòk, students used terms like danger, instability, violence, stress, gangs, guns, impunity, and the lack of authority. Students said they felt threatened every day and saw videos of bodies circulating on social media. Several students lost friends or family members to violence and 2 students reported having people killed in front of them. These events in particular resulted in serious self-reported psychological distress for students. In addition, there was the strong presence of gangs in the violence and chaos of peyi lòk. One study on the increasing problem of gangs in Haiti describes them as “omnipresent groups” that can overthrow governments, silence opposition, terrorize entire cities, and facilitate a burgeoning kidnapping industry, adding “it is impossible to discuss Haiti without addressing the issue of gangs” [50]. All of this “apparent violence,” as one student put it, contrasts with the relative calm of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In their justifications which minimized the gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic, students mentioned how Haiti has dealt with worse pandemics in the past, such as the 2010 cholera pandemic which infected 900,000 and killed over 9,000 Haitians [51]. Others mentioned that while COVID-19 was feared in the early months, by the time this study was conducted in the Fall 2020, few believed it remained a serious threat to Haiti. Parallel to this reasoning that Haitians have dealt with worse pandemics in the past was the argument that “Haitians are used to political crises,” a sentiment shared by 2 different students. As the unrest that culminated in peyi lòk started years earlier, students expressed a certain resignation about political deadlock and the resulting protests and violence, particularly in the cities.

Yet, a significant percentage of students maintained that COVID-19 was more serious than even the violence of peyi lòk. Many of these students live in the countryside, however, where they were less affected by the urban-focused peyi lòk and more impacted by the national COVID-19 lockdown. One student talked about how people in his rural community were afraid of outsiders in the early days of the pandemic, as they thought people could come in and infect them. Others highlighted the general uncertainty surrounding the virus and its potential consequences, emphasizing their fear of the unknown. With peyi lòk they knew it had to come to an end someday, they said, whereas with the COVID-19 lockdown, “we didn’t know when the shutdown would end.” Lastly, the extent to which students resigned themselves to religious beliefs or God also emphasizes the fear that this poorly understood virus instilled in the population, even among the most educated.

The purpose of this study was to describe the mental health and psychological effects of two recent crises on a sample of Haitian public health university students in their own words. This data is intended to inform future studies on the relationship between social and political crises, and mental health care and treatment in Haiti. The results of this study found that both crises were characterized by a shutdown of normal life, such as an inability to go to work or school. Due to this inability to make a living, both crises also resulted in extreme economic hardship for students, with many reporting difficulties accessing basic needs such as food and water. Both crises also resulted in significant increases in stress and fear. However, the extreme violence of peyi lòk resulted in higher levels of reported stress among participants, whereas the widespread uncertainty around COVID-19 and its effects in the early days of the pandemic resulted in high levels of fear.

While this study did not categorize psychological symptoms with corresponding criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), there is significant overlap with many symptoms described and disorders such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress [52]. Additionally, the experience of traumatic events, chronic stress, fear, and anxiety are known to result in more serious mental disorders in many individuals [53].

Several recent studies have examined the relationship between mental health and psychological well-being in the context of different crises in places around the world [54–57]. While these studies largely focus solely on either economic or social crises, the recent examples of peyi lòk and the COVID-19 lockdown in Haiti highlight the multi-faceted nature of these crises in the country. Though significantly different in terms of their causes, both of these crises also had similarities in terms of the psychological effects on young people, most notably in terms of traumatic experiences of threats or violence, forced confinement, economic distress, and large increases in population-wide stress and fear. While already experiencing the chronic stress of living in a “fragile state,” the trauma of acute crises that overlay the chronic crises can add an additional burden on the health and psychological well-being of young Haitians which may result in severe mental distress.

4.2 COVID-19 and Belief Systems

Although little has been published about the COVID-19 pandemic in low-income countries thus far, two studies have looked at the extent to which rumors and misinformation were able to spread throughout Haiti, particularly on social media. These studies reflect the accounts presented by students in which 14 remarked on high levels of stigma around the virus, 7 discussed conspiracy theories or skepticism about the existence of the virus, and another 7 highlighted the way information now spreads via social media channels. One study described rumors in Haiti saying that the virus is transmitted by contaminated testing swabs, or that hospitals are using patients for vaccine experiments [58] Another described the conspiracies circulating in Haiti that COVID-19 is a result of sin and is God’s punishment on humans for their sinful ways, that the world’s elite manufactured the virus to kill minorities and people in poor countries, or that the vaccine will render people in poor countries sterile so that they do not produce so many children [59]. While some Haitians have accurate information and understand these are falsehoods, there are reports in Haiti of hospital staff being threatened and physically attacked, including the stoning of Ministry of Health mobile testing teams [58].

Additionally, the fear of a deadly and unknown global pandemic in places like Haiti results in an “automatic magico-religious response when it comes to diseases like COVID-19” according to one Haitian scholar’s exhaustive analysis of the country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Several studies other have documented the preponderant role of Vodou and leaf-based treatments in traditional healing in the country [60–62]. For this reason, it is perhaps unsurprising that the COVID-19 crisis resulted in a return to traditional medicine in many parts of Haiti. As one study describes, many different recipes were used to combat the virus, including aloe and a variety of other leaves and roots. This study also cites cases of COVID-19 among the Haitian diaspora in Florida where people “recovered” after consuming some of these “notorious beverages” [18].

Perhaps the most significant negative impact on the mental health of young Haitians according to participant accounts in this study was economic challenges including employment and access to food. In this sense, as Etienne describes, food insecurity became severe due to the “combined shocks of peyi lòk in 2019 as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, when the most vulnerable households were exposed” by this accumulation of crises [4]. One student whose mother could not work during either crisis described how he was able to eat enough during peyi lòk, but when the pandemic lockdown arrived a few months after it ended he was no longer able to eat his fill. This testimony highlights the cumulative effects that repeated acute crises—on top of chronic structural crises—can have on physical and mental well-being.

With high percentages of young people compared to middle- and high-income countries, low-income countries like Haiti face a continual challenge of providing food, education, housing, jobs, and stability for their future leaders [63]. After instances of corruption such as the Petrocaribe scandal, many in Haiti argue that their government does little to nothing to provide a decent future for its youth. In fact, Haitian government policy has encouraged emigration as a solution to the “demographic problem” the country is facing, according to one Haitian expert [6]. Yet, the international community has failed Haiti in the recent past as well, in particular with the loss and misappropriation of billions of dollars among the $9 billion raised for post-earthquake reconstruction [64,65]. The problem and complexity of long-term stability and crisis prevention in Haiti were also evinced by the cholera outbreak stemming from UN peacekeepers, highlighting the international community’s contribution to Haiti’s instability at times as well [66].

Young people in Haiti continue to be forced to live through repeated crises. As the vast majority of Haitians were born since the 1986 departure of the dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier—or “Baby Doc” as he is widely known—they have never known a country without extended periods of crisis. This exposure to chronic stress, fear, and traumatic events such as unrest, extreme violence, and natural disasters, is proven to result in mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and other disorders including post-traumatic stress. Several studies have demonstrated this relationship in Haiti itself, showing increased incidents of mental illness and suicidality among young people, and highlighting the inability of existing services to offer adequate treatment or care [67,68].

While preventing national or global crises—like that of peyi lòk or COVID-19 respectively—is exceedingly complex and difficult, services that provide effective therapies for survivors can address the wounds on a more individual level, and should be adapted and implemented locally [46]. With only one mental health clinic in the entire northern region of the country—started recently in 2016—few biomedical service options are available for a population that continues to overwhelmingly seek care with Vodou priests (ougan) and other traditional healers [69]. In addition to providing individual-level care, community-level interventions should be considered as well, in order to restore community cohesion and promote resilience in the event of future crises [70].

This study had several limitations. Firstly, while students were all chosen from the same Public Health program at UPNCH, they were not randomly selected. Rather they were chosen based on their availability and willingness to participate, which opens the possibility for selection bias within UPNCH. Thus, it is unclear whether the sample chosen for this study is generally representative of students at UPNCH. Additionally, as these are students receiving an undergraduate education in public health, they are likely more educated and aware of the relationship between crisis and mental health compared with the broader university population in Haiti. For this reason, they may not be representative of a community of Haitian university students.

Next, there is a potential for reporting bias in this study as students may be underreporting undesirable effects of the crises. As these interviews were conducted in the context of focus groups with their peers, some students may have limited the discussion of difficult experiences they had during these periods. Additionally, as these discussions took place in front of a researcher from the United States, it is possible that this influenced the response patterns of the participants. Social desirability bias may have led them to portray responses that they believe were more socially acceptable rather than those that are reflective of their true feelings or experiences. Lastly, the discussions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic took place while the pandemic was still ongoing in the Fall of 2020. Changes in the consequent months of the pandemic may impact overall perceptions or experiences of this crisis.

This study assessed the impact of two current crises—peyi lòk and the COVID-19 pandemic—on the mental health of youth in Haiti. In particular, this study found strong impacts of these crises on the lived experiences of students interviewed. With regards to peyi lòk, students were severely impacted by widespread violence and insecurity resulting in high levels of stress, as well as concern for the safety of loved ones. During the COVID-19 pandemic, students highlighted substantial uncertainty, fear, and stigma surrounding the new virus. In conjunction with already existing political violence and pervasive poverty, the youth interviewed described significant trauma-related impacts on their lives and Haitian society as a whole. As this study was conducted prior to the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse on July 07, 2021, we did not examine the impacts of this event and its fallout. Future research on mental health and crisis in Haiti could further examine the physical and psychological consequences of large-scale crises in communities, including the impact of Moïse’s assassination and the ramifications for Haitian society.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Giafferi, N. (2003). Couleur et rang dans la Caraibe : une ethnologue face aux discours et aux luttes du classement socio-racial dans la ville de Port-au-Prince (Haiti) (Doctoral Dissertation, Aix-Marseille 3). [Google Scholar]

2. Eugène, M. M. (2020). Haïti a mal à sa pauvreté. L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

3. Jean, F. A. (2019). Haïti Une Economie de Violence : Instabilité Politique et Violence Economique. [Google Scholar]

4. Etienne, W. (2020). Haïti face à la gestion de la pandémie du COVID-19 : Contraintes, stratégies et conséquences. [Google Scholar]

5. Germain, E. (2019). Pourquoi Haïti Peut Réussir. [Google Scholar]

6. Michel, G. (2019). Bak Lakay. Imprimerie Brutus. [Google Scholar]

7. Wagenaar, B. H., Kohrt, B. A., Hagaman, A. K., McLean, K. E., Kaiser, B. N. (2013). Determinants of care seeking for mental health problems in rural Haiti: Culture, cost, or competency. Psychiatric Services, 64(4), 366–372. DOI 10.1176/appi.ps.201200272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Nicolas, G., Jean-Jacques, R., Wheatley, A. (2012). Mental health counseling in Haiti: Historical overview, current status, and plans for the future. Journal of Black Psychology, 38(4), 509–519. DOI 10.1177/0095798412443162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Aristide, J. B. (2011). Haïti-Haitii : Pwezi filosofik pou dekolonizasyon mantal. [Google Scholar]

10. Piarroux, R. (2011). Understanding the cholera epidemic, Haiti. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 17(7), 1161–1168. DOI 10.3201/eid1707.110059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Pierre-Paul, M. (2019). Peyi Nou Ka Chanje. [Google Scholar]

12. UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) (2018). Gross Domestic Product per Country around the Globe. [Google Scholar]

13. Michel, G. (2021). Jèm Lakay. Pro Editions. [Google Scholar]

14. Lalime, T. (2010). Croissance économique et instabilité politique en Haïti (1970–2008). [Google Scholar]

15. Mullet, A., Thomas, F. (2020). Demonstrations, corruption, paralysis…Ten years after the earthquake of January 12, 2010, Haiti lives in a state of permanent crisis-Centre tricontinental. [Google Scholar]

16. Raviola, G., Rose, A., Fils-Aimé, J. R., Thérosmé, T., Affricot, E. et al. (2020). Development of a comprehensive, sustained community mental health system in post-earthquake Haiti, 2010–2019. Global Mental Health, 7, e6. DOI 10.1017/gmh.2019.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Beckett, G. (2020). Unlivable life: Ordinary disaster and the atmosphere of crisis in Haiti. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, 24(2), 78–95. DOI 10.1215/07990537-8604502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Henrys, J. H. (2020). Haïti : d’une pandémie à l’autre, du choléra au COVID-19. HAÏTI ET LE COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

19. Cénat, J. M. (2020). The vulnerability of low-and middle-income countries facing the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Haiti. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 37, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

20. O’Hare, M., Hardingham, T. (2020). Coronavirus—Which countries have travel bans? CNN. [Google Scholar]

21. Charles, J. (2020). Haiti declares early victory over coronavirus, plans to reopen factories. Miami Herald. [Google Scholar]

22. JHU (Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center) (2020). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. [Google Scholar]

23. US Embassy (2020). COVID 19 Information. https://ht.usembassy.gov/covid-19-information/. [Google Scholar]

24. PAHO (Pan American Health Organization) (2020). PAHO Director calls on each country to analyze trends of the pandemic before relaxing social distancing measures. [Google Scholar]

25. Martsolf, D. (2004). Childhood maltreatment and mental and physical health in Haitian adults. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(4), 293–299. DOI 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04054.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Belik, S. L., Cox, B. J., Stein, M. B., Asmundson, G. J., Sareen, J. (2007). Traumatic events and suicidal behavior: Results from a national mental health survey. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(4), 342–349. DOI 10.1097/01.nmd.0b013e318060a869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kaniasty, K. (2012). Predicting social psychological well-being following trauma: The role of postdisaster social support. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(1), 22–33. DOI 10.1037/a0021412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Park, C. L., Gutierrez, I. A. (2013). Global and situational meanings in the context of trauma: Relations with psychological well-being. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 8–25. DOI 10.1080/09515070.2012.727547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Almedom, A. M., Summerfield, D. (2004). Mental well-being in settings of ‘complex emergency’: An overview. Journal of Biosocial Science, 36(4), 381–388. DOI 10.1017/S0021932004006832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Surya, M., Jaff, D., Stilwell, B., Schubert, J. (2017). The importance of mental well-being for health professionals during complex emergencies: It is time we take it seriously. Global Health: Science and Practice, 5(2), 188–196. [Google Scholar]

31. Kohrt, B. A., Carruth, L. (2020). Syndemic effects in complex humanitarian emergencies: A framework for understanding political violence and improving multi-morbidity health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine, 295, 113378. [Google Scholar]

32. Ventevogel, P., Ommeren, M. V., Schilperoord, M., Saxena, S. (2015). Improving mental health care in humanitarian emergencies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 93(10), 666. DOI 10.2471/BLT.15.156919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Quinn, V., J., M. (2017). Disaster, war, conflict, complex emergencies and International public health risks. [Google Scholar]

34. Sumathipala, A. (2017). Psychiatric emergencies in disaster situations. In: Emergencies in psychiatry in low-and middle-income countries, pp. 94–103. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

35. Auguste, E., Rasmussen, A. (2019). Vodou’s role in Haitian mental health. Global Mental Health, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

36. Willman, A., Marcelin, L. H. (2010). “If they could make us disappear, they would!” Youth and violence in cite Soleil, Haiti. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(4), 515–531. DOI 10.1002/jcop.20379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Logie, C. H., Daniel, C., Ahmed, U., Lash, R. (2017). ‘Life under the tent is not safe, especially for young women’: Understanding intersectional violence among internally displaced youth in Leogane, Haiti. Global Health Action, 10(sup2), 1270816. DOI 10.1080/16549716.2017.1270816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Lai, B. S., Osborne, M. C., de Veauuse-Brown, N., Swedo, E., Self-Brown, S. et al. (2020). Violence victimization and negative health correlates of youth in post-earthquake Haiti: Findings from the cross-sectional violence against children survey. Journal of Affective Disorders, 270(2), 59–64. DOI 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. CIA (2020). The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/fields/343.html. [Google Scholar]

40. Jaimes, A., Lecomte, Y., Raphael, F. (2008). Haïti-Québec-Canada: Towards a partnership in mental health. Online Symposium Summary. www.haitisantementale.ca. [Google Scholar]

41. Kolbe, A. R., Hutson, R. A. (2006). Human rights abuse and other criminal violations in Port-au-Prince, Haiti: A random survey of households. The Lancet, 368(9538), 864–873. DOI 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69211-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kolbe, A. R., Hutson, R. A., Shannon, H., Trzcinski, E., Miles, B. et al. (2010). Mortality, crime and access to basic needs before and after the Haiti earthquake: A random survey of Port-au-Prince households. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 26(4), 281–297. DOI 10.1080/13623699.2010.535279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Shultz, J. M., Marcelin, L. H., Madanes, S. B., Espinel, Z., Neria, Y. (2011). The “Trauma Signature:” Understanding the psychological consequences of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 26(5), 353–366. [Google Scholar]

44. James, L. E., Welton-Mitchell, C., Noel, J. R., James, A. S. (2020). Integrating mental health and disaster preparedness in intervention: A randomized controlled trial with earthquake and flood-affected communities in Haiti. Psychological Medicine, 50(2), 342–352. DOI 10.1017/S0033291719000163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Cadichon, J. M. (2019). Narrations du Sensible : Récits post-traumatiques de survivants du séisme du 12 janvier 2010 en Haïti. Editions de l’Université d’Etat d’Haïti. [Google Scholar]

46. Bolton, P., Surkan, P. J., Gray, A. E., Desmousseaux, M. (2012). The mental health and psychosocial effects of organized violence: A qualitative study in Northern Haiti. Transcultural Psychiatry, 49(3–4), 590–612. DOI 10.1177/1363461511433945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Bolton, P., Tang, A. M. (2004). Using ethnographic methods in the selection of post-disaster, mental health interventions. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 19(1), 97–101. DOI 10.1017/S1049023X00001540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Galvin, M., Chapnick, M., Antenor, L., Joseph, D., Dulience, B. et al. (2020). Transnational educational partnerships: Achieving public health impact through cross-cultural pedagogical approaches in Haiti. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 60(4), 204–216. DOI 10.1080/14635240.2020.1843187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Afram Plains: Residents Search for Hair in Bible to Prevent Coronavirus (2020). https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/entertainment/Afram-Plains-Residents-search-for-hair-in-Bible-to-prevent-coronavirus-905668. [Google Scholar]

50. Kolbe, A. R. (2013). Revisiting Haiti’s gangs and organized violence. HASOW, Rio de Janeiro. [Google Scholar]

51. UN (United Nations) (2016). New UN System Approach to Cholera in Haiti. [Google Scholar]

52. APA (American Psychiatric Association) (2020). https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm. [Google Scholar]

53. Galvin, M. (2020). Effective treatment interventions for global mental health: An analysis of biomedical and psychosocial approaches in use today. Psychology and Mental Health Care, 4(3), 1–14. DOI 10.31579/2637-8892/076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Tremblay, J., Pedersen, D., Errazuriz, C. (2009). Assessing mental health outcomes of political violence and civil unrest in Peru. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 55(5), 449–463. DOI 10.1177/0020764009103214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Uutela, A. (2010). Economic crisis and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 23(2), 127–130. DOI 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328336657d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Bartoll, X., Palència, L., Malmusi, D., Suhrcke, M., Borrell, C. (2014). The evolution of mental health in Spain during the economic crisis. The European Journal of Public Health, 24(3), 415–418. DOI 10.1093/eurpub/ckt208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Bhargava, R., Gupta, N. (2020). Social unrest and its impact on mental health. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, 36(1), 3–4. DOI 10.4103/ijsp.ijsp_27_20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Rouzier, V., Liautaud, B., Deschamps, M. M. (2020). Facing the monster in Haiti. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(1), e4. DOI 10.1056/NEJMc2021362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Louis-Jean, J., Cenat, K., Sanon, D., Stvil, R. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Haiti: A call for action. Journal of Community Health, 45(3), 1–3. DOI 10.1007/s10900-020-00825-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Meudec, M. (2007). Le kout poud : maladie, vodou et gestion des conflits en Haïti. Editions L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

61. Vonarx, N. (2008). Vodou et pluralisme médico-religieux en Haïti : du vodou dans tous les espaces de soins. Anthropologie et Sociétés, 32(3), 213–231. [Google Scholar]

62. Pierre, A., Minn, P., Sterlin, C., Annoual, P., Jaimes, A. et al. (2010). Culture et santé mentale en Haïti : une revue de littérature. Santé mentale au Québec, 35(1), 13–47. DOI 10.7202/044797ar. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Ortiz, I., Cummins, M. (2012). When the global crisis and youth bulge collide: Double the jobs trouble for youth. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2029794. [Google Scholar]

64. Bilham, R. (2010). Lessons from the Haiti earthquake. Nature, 463(7283), 878–879. DOI 10.1038/463878a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Ramachandran, V., Walz, J. (2015). Haiti: Where has all the money gone? Journal of Haitian Studies, 21(1), 26–65. DOI 10.1353/jhs.2015.0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Lemay-Hébert, N. (2014). Resistance in the time of cholera: The limits of stabilization through securitization in Haiti. International Peacekeeping, 21(2), 198–213. DOI 10.1080/13533312.2014.910399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Wagenaar, B. H., Hagaman, A. K., Kaiser, B. N., McLean, K. E., Kohrt, B. A. (2012). Depression, suicidal ideation, and associated factors: A cross-sectional study in rural Haiti. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 149. DOI 10.1186/1471-244X-12-149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Hagaman, A. K., Wagenaar, B. H., McLean, K. E., Kaiser, B. N., Winskell, K. et al. (2013). Suicide in rural Haiti: Clinical and community perceptions of prevalence, etiology, and prevention. Social Science & Medicine, 83, 61–69. DOI 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Galvin, M., Michel, G. (2020). A haitian-led mental health treatment center in Northern Haiti: The First step in expanding mental health services throughout the region. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(2), 127–138. DOI 10.1080/13674676.2020.1737921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Ventevogel, P. (2016). Borderlands of mental health: Explorations in medical anthropology, psychiatric epidemiology and health systems research in Afghanistan and Burundi. Peter Ventevogel. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools