Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Preventing Health Anxiety: The Role of Self-Evaluation, Sense of Coherence, Self-Rated Health and Perceived Social Support

1 Department of Sport Sciences, Eszterházy Károly Catholic University, Eger, 3300, Hungary

2 Department of Special Needs Education, Eszterházy Károly Catholic University, Eger, 3300, Hungary

* Corresponding Author: Mónika Csibi. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(10), 1081-1088. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.029390

Received 16 February 2023; Accepted 26 April 2023; Issue published 03 November 2023

Abstract

Background: Components of Self, completed with the perceived social support determine the individual differences in the evaluation of a stressor and the behavioral responses toward it, such as health-related anxiety. The study set as a goal the analysis of associations between the components of Self, such as self-evaluation, sense of coherence, perceived social support, and reported health-related anxiety in an adult sample. Methods: 147 adults from the 18–73 age group (mean age 37.5) voluntarily completed the questionnaire through Qualtrics online platform containing the Short Health Anxiety Inventory, Core Self-Evaluation Scale, Social Support Assessing Scale, and one Health Self-Evaluation Item. Results: ANOVA found relevant differences in total scores and subscales’ scores of the health anxiety scale depending on the positive self-evaluation. Linear regression shows that the analyzed variables were responsible for the prediction of a higher value on the “Perceived probability of becoming ill” subscale in a proportion of 45.6% and for the “Perceived consequence of illness” subscale in a proportion of 20.2% The predictive value of the linear regression model for the total score on the health anxiety scale was 46.3%. Our findings show that negative Core Self-Evaluation is linked with perceived health anxiety. Conclusions: Self-evaluation, sense of coherence and perceived social support influence the perceived health and can explain the differences in the reported health-related anxiety.Keywords

Experiencing health denotes an individual state of mind, coping, emotions, and life goals, along with perceptions about self, personal health, and health-related behavior. More specifically the components of Self, integrated into one’s personality define the evaluation of health (perceived health), which explains the individually different experiences of the same state of health. A crystallized core self-evaluation is a potential and broad personality structure considered a negative predictor of anxiety [1,2]. Studies document that, individuals with high core self-evaluation show greater confidence in life, a better sense of control over their life, and less anxiety [3,4]. From the developmental perspective, a generally stable and positive self-concept is beneficial not only for educational and work-related achievements but for establishing a social and academic identity and a level of overall well-being. Research in the field agrees that a well-structured self-concept helps individuals to predict and understand different situations, opportunities, and constraints, including thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, while low self-esteem and a negative self-image are the hallmarks of many psychological disorders [5,6]. Core self-evaluation can be useful in explaining individual differences in the evaluation of a stressor and the responses toward it. The definition of self-evaluation emphasizes the beliefs about the self, and perceived personal control, as key components of an individual’s view of the world and ability to function successfully in daily life [7].

The concept of social self-image includes self-related cognitions and awareness of skills and abilities playing a significant role in the development and maintenance of self-perception [8]. Thus, individual differences in aspects of self-perception are explained through the quality of predictions about social performance, cognitions related to self, thoughts, and perceptions about self-assessment of a social situation [9,10]. Perceived social support appears as one of the factors decreasing general anxiety levels, with its mental and physical health-protective role. The presence and perception of social support in personal interactions can be understood as a self-evaluation of provided support and individual satisfaction with such support [11]. Conscientizing the level of perceived and received support is relevant in the manifestation of one’s health-related anxiety. Perceived social support is anchored in one’s personality structure and predicts mental health to a greater extent than objective social support [12,13].

Anxiety in general refers to an unpleasant inner conflict that an individual has in the face of an upcoming event that may pose a threat, accompanied by certain emotional and physical symptoms, such as anger, tension, insomnia, and stomach pain [14]. Scientists conceptualize the construct of health anxiety as a continuum, from low concerns or preoccupation with health to pathological levels identified as a psychiatric diagnosis [15,16], such as hypochondriasis [17] or illness anxiety disorder [18]. The term health anxiety itself refers to a continual, unfounded, and excessive fear of a possible medical condition. The excessive preoccupation with health-related symptoms based on a misperception of body functioning may actuate specific behaviors, such as the increased use or avoidance of medical services, which in turn may lead to a dysfunctional daily routine [19,20]. Empirical research concludes that health anxiety can be viewed as a non-pathological construct associated with personality traits and behavior and has structural differences depending on the disease’s frequency [21]. In the specialty literature, the clinical syndrome characterized by excessive health-related worries and disease conviction has been termed “hypochondriasis” [22]. However, the American Psychiatric Association [18] removed the term “hypochondriasis” from the latest versions of its classification of mental disorders and included two different clinical syndromes, that is, illness anxiety disorder and somatic symptom disorder [18]. The specified symptomatology differentiates between illness anxiety disorder, characterized by none or weak somatic symptoms, and somatic symptom disorder, in which case the person reports clinically relevant somatic symptoms. Related behavior includes seeking evidence of illness in one’s own body, searching for information on dreaded illnesses and seeking reassurance, or avoiding health information [18].

Research suggests the existence of a positive association between the severity of somatic symptoms and levels of health anxiety, reinforced by the selective and often distortional perception of body experiences and observations [23–25].

Concerning demographic specifics, in their study Santoro et al. find that younger age was associated with higher levels of health anxiety [26]. These results show a difference from previous evidence which suggested that older adults are more characterized by health anxiety [27,28].

The present study aims to examine the level of reported health anxiety associations with self-evaluation, sense of coherence, self-rated health status, and perceived social support among adults. We assume that a higher level of health anxiety is related to a negative self-image, low level of sense of coherence, low perceived social support, and self-rated health status. Although the present study focuses on the assessment of health anxiety, which had been described in literature plenty of times, along with the self-evaluation and a sense of coherence, we attempt to reveal and reinforce the previous international results in the Hungarian sample. An added value of the paper consists also of the reflections on the age-related variations of self-evaluation, self-rated health, and perceived health anxiety. This study provides a good starting point for future deeper study of the specificities of the analyzed variables from an age developmental perspective.

The objective of the research was to analyze the associations between health anxiety and self-evaluation, sense of coherence, self-rated health status, and perceived social support in a non-clinical, adult sample.

We hypothesize a significant association between self-evaluation, a sense of coherence, perceived social support, and the level of health-related anxiety.

Participants: 147 Hungarian adults completed the questionnaires through Qualtrics online platform. The participants completed the survey voluntarily, including their consent toward anonym data use for research purposes. The call for completing the survey was made through social media (Facebook groups) and student groups forums. We obtained 156 answer sets and 9 cases were removed because of incomplete data. 147 surveillances were subjected to analysis.

Concerning age, they belonged to the 17–73 age group (M = 37.5), with 31 males, and 116 females. In assessing age differences, the Kail and Cavanaugh stage of life classification system was used. The authors divide adult subjects into four age groups: 18–26 years, 27–35 years, 36–45 years, and 46+ years [29]. In our sample, the age group distribution was: 18–26 (N = 38, 25.9%), 27–35 (N = 24, 16.3%), 36–45 (N = 44, 29.9%), and 46+ (N = 41, 27.9%).

In the present study, we obtained data about the reported level of anxiety through the Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI) [30].

The 18-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI) [30] provides the assessment of the degree of perceived health anxiety and contains two subscales: “perceived probability of becoming ill”, and “perceived consequence of illness”. The authors suggested that in interpreting the results of testing with SHAI higher scores reflect higher health anxiety, and did not identify a cut-off point. Other analysts distinguished between clinical and non-clinical samples, and suggested, that different cut-off points may be indicated in the interpretation of scores [31]. Adapted versions of SHAI suggest a cut-off score of 20 for the non-clinical population, and the Hungarian version refers to a score of 33.02 (SD = 6,277) for the total scale [32,33]. In our sample, the mean total score was 32 (SD = 5.89), the “perceived probability of becoming ill” mean score was 24.38 (SD = 4.65), and the “perceived consequence of illness” mean score was 7.53 (SD = 2.34). The reliability coefficient was 0.79.

For the evaluation of the personality-related components, we used several psychological instruments, included in an online questionnaire.

We used the 12-item Core Self-Evaluation Scale (CSES) [34] (version validated on the Hungarian population), assessing the level of self-esteem using a five-point Likert format with options ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5) and with high scores denoting high core self-evaluations. In our sample, the scale showed good reliability (α Cronbach 0.86).

The Sense of Coherence Scale [35], a seven-item Hungarian validated form [36], is measuring the degree of organization of the psycho-emotional processes necessary for behavior consistent with one’s own experiences. The scale consists of 7 items, with respondents indicating their agreement with each item on a three-point scale (0,1,2), higher scores mean a more increased sense of coherence. In our sample, the mean score was 17,249 (SD = 2.90), Cronbach α 0.77.

Participants also completed the Hungarian-Validated Social Support Assessing Scale (MOS-SSS, 20 items) [37,38], assessing the degree of perceived acceptance and emotional support (M = 90.06, SD = 18.64) and contains three subscales: “emotional/informational support” (M = 33.87, SD = 7.22), “positive social interaction support” (M = 30.62, SD = 6.11) and “Instrumental support” (M = 19.82, SD = 3.52). α Cronbach 0.81. The scale contains 20 items, with a possible score between 19 and 95; a higher score means stronger support.

In addition, one item was used for self-rated health, for measuring self-assessed health status (“How do you rate your health compared to your peers?”), with the response options ranging from 1 = very poor to 5 = excellent. In our sample, the distribution of the self-rated health scores in our sample showed poor 2%, moderate 23.12%, good 59.92%, and very good 15.2%.

In our data analysis, we performed descriptive statistics, correlation, t-test, ANOVA, and linear regression to identify the predictive role of the variables. Statistics were realized using IBM SPSS ver. 21 programs. The distributions of scores on measures met assumptions of normality.

For descriptive statistical considerations, we studied gender and age data in association with the health anxiety scale (ANOVA Bonferroni test for age and t-test for gender). Our analysis did not show significant differences by gender.

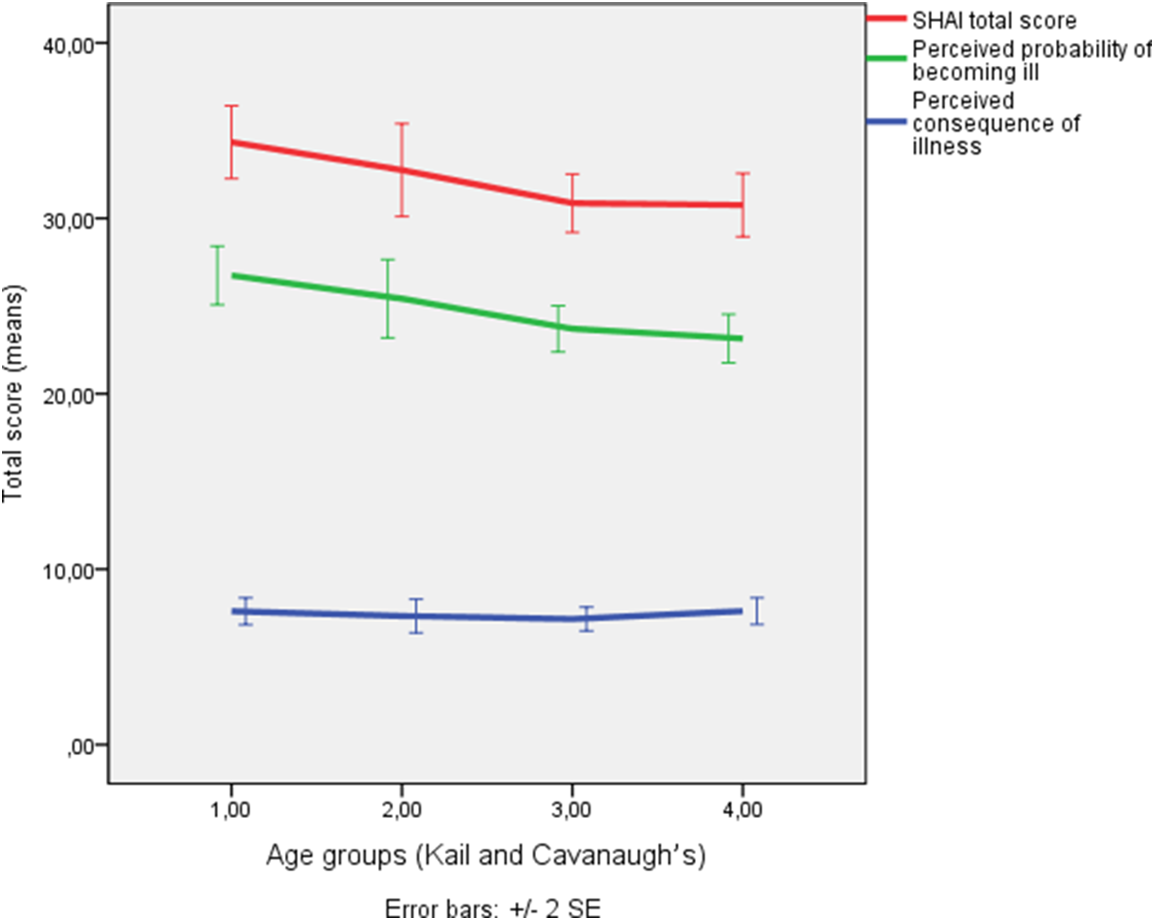

On the other hand, considering age differences, we found lower values on the total score of health anxiety and the “perceived probability of becoming ill” subscale scores in the 36–45 age group, compared to younger age groups. The “perceived consequence of illness” subscale’ scores show roughly similar values (Fig. 1). In our analysis we considered age groups using Kail and Cavanaugh’s stage of the life classification system, dividing adult subjects into four age groups: (1) 18–26 years, (2) 27–35 years, (3) 36–45 years, and (4) 46+ years [29].

Figure 1: Health anxiety mean score distribution by age group.

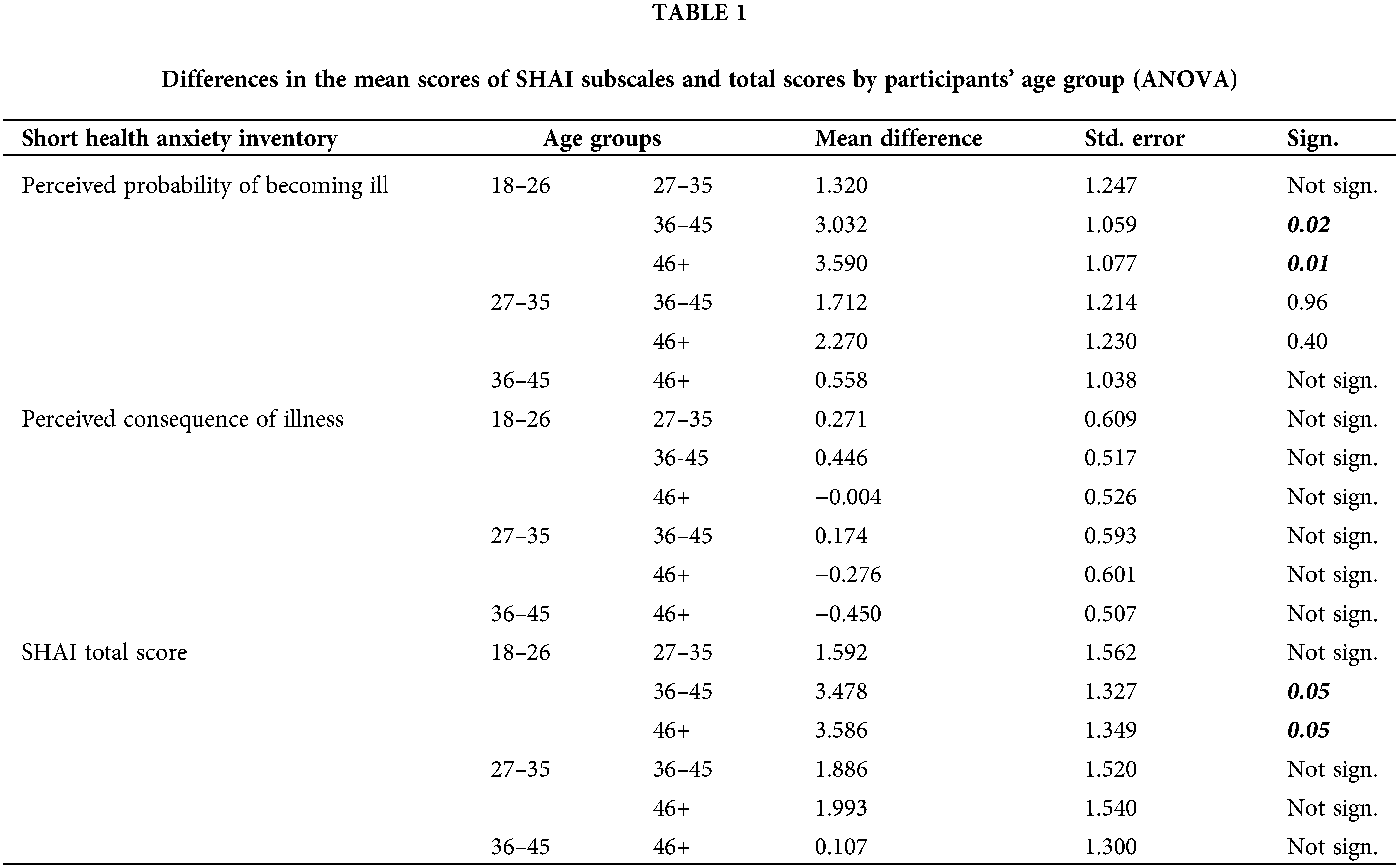

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) evidenced significant differences for the SHAI subscales and total scores, as well as by age group, between the 18–26, and the 36–45, 46+-year-olds, for “Perceived probability of becoming ill” and “SHAI total score” (Table 1).

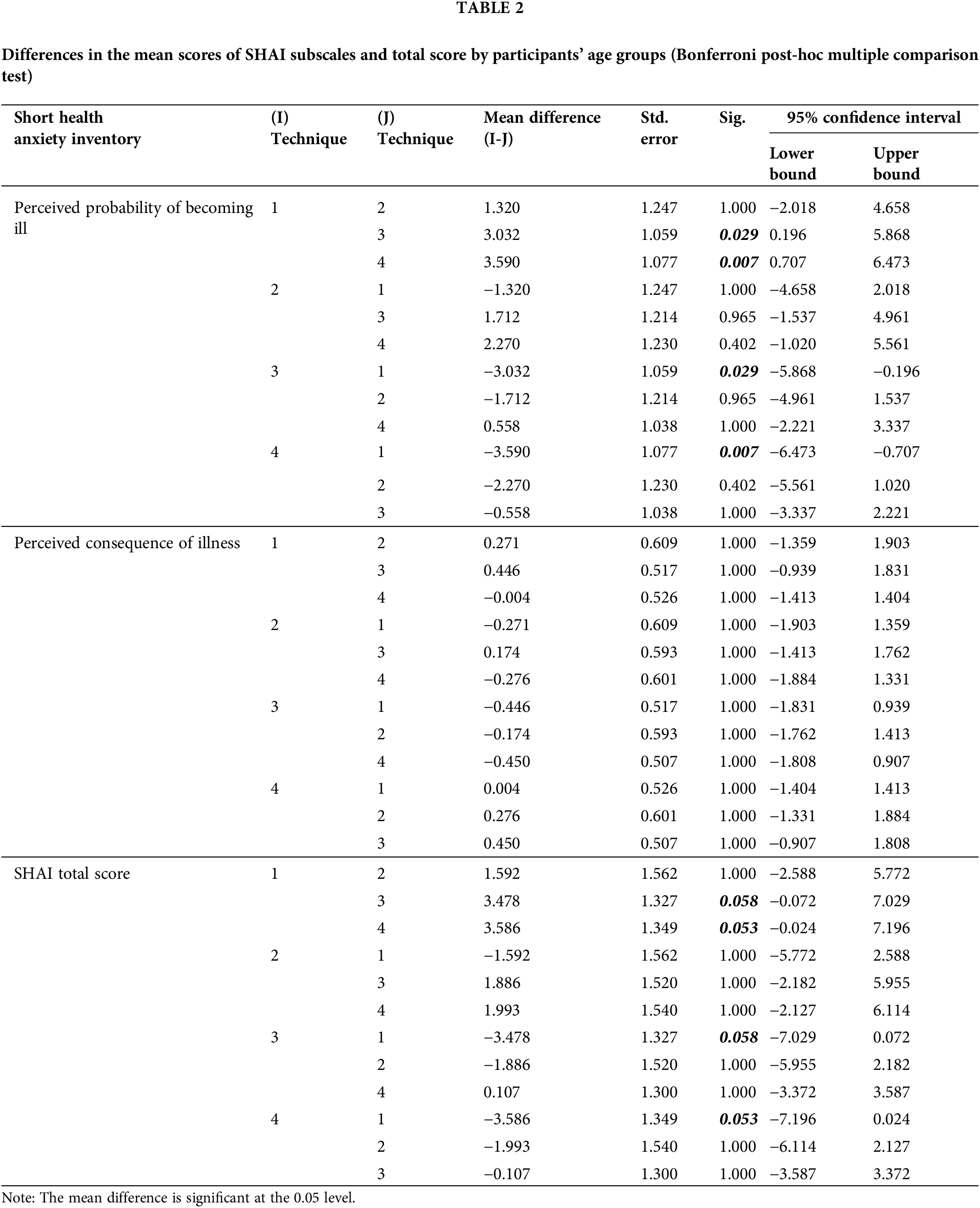

Thus, we found a relevant association between the core self-evaluation, sense of coherence, and health-related anxiety total score and both subscales, the perceived probability of becoming ill, and perceived consequences of illness. Furthermore, the Bonferroni post hoc multiple comparison tests proved differences in the mean scores of SHAI subscales and total scores by participants’ age groups. A lower score on core Self-Evaluation (F (3, 143) = 4.42, p < 0.001) and social support (F (3, 143) = 1.78, p = 0.017) were related to respondents’ higher total score of health anxiety (see Table 2).

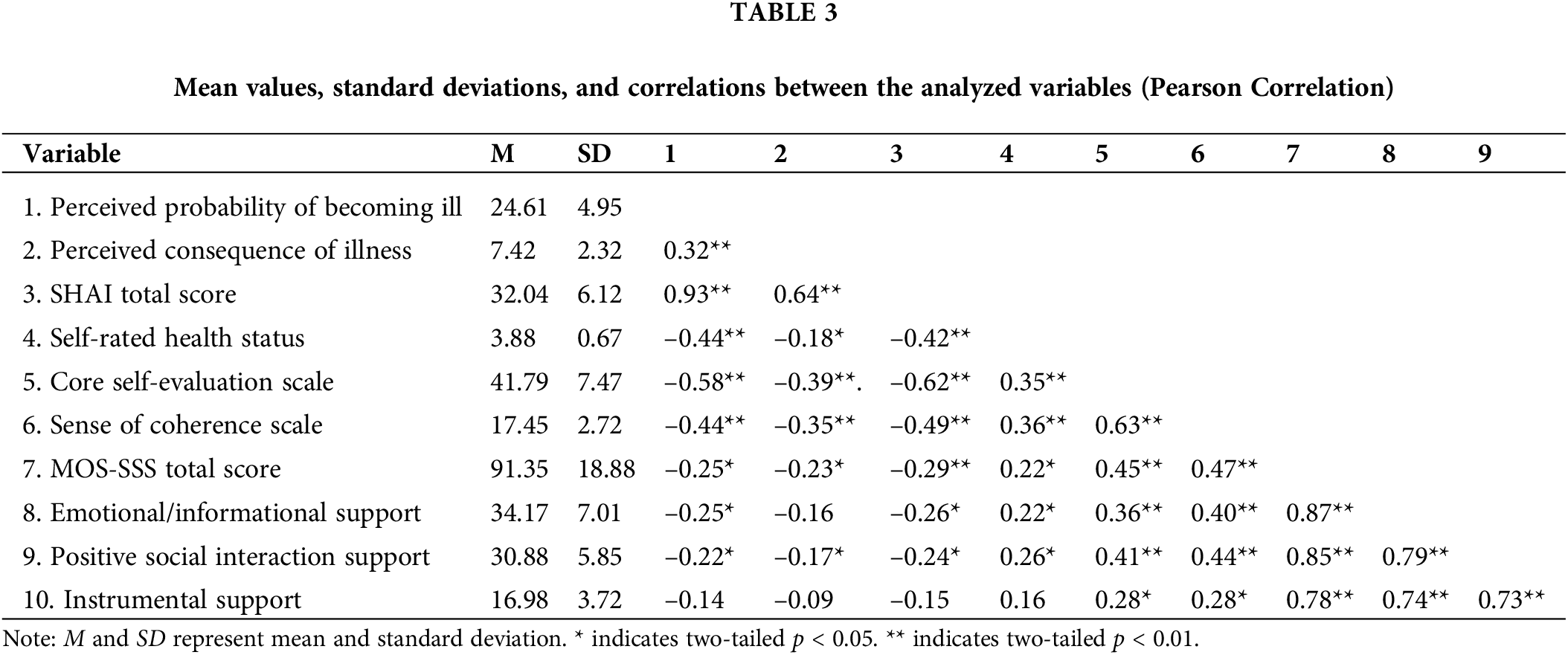

In the next step to verify our hypothesis, we performed correlation analysis. The obtained results show a relevant association between the core self-evaluation, sense of coherence, and health-related anxiety total score and both subscales, the perceived probability of becoming ill, and perceived consequences of illness in our sample (Table 3).

Further, we performed linear regression analysis, for the identification of the predictive properties of our variables. In all three regression models (for the health anxiety total scale and two subscales), we included as variables the gender, age group, scores on psychological scales and subscales, and the one-item score of self-rated health.

The introduced variables were responsible for the prediction of a higher value on the “Perceived probability of becoming ill” subscale in a proportion of 45.6% (R2 = 0.456, F (9, 137) = 12.73, p < 0.001), and for the “Perceived consequence of illness” subscale in a proportion of 20.2% (R2 = 0.202, F (9, 137) = 3.85, p < 0.001). The predictive value of the linear regression model for the total score on the health anxiety scale was 46.3% (R2 = 0.463, F (9, 137) = 13.11, p < 0.001).

Our data show that respondents characterized by an increased core self-evaluation report a lower rate of health anxiety. These results are in line with studies in the field sustaining that high core self-evaluation is a reliable predictor of lower perceived psychological distress and increased well-being in adults [39]. Besides, individuals who face positive emotions and/or are satisfied with their lives and simultaneously show high core self-evaluation demonstrate better physical health functioning [40]. Therefore, Pujol-Cols and Lazzaro-Salazar argued that core self-evaluation moderated the relationship between emotional demands and physical health, suggesting that the negative effects of emotional demands on physical health are higher for those individuals with less positive core self-evaluation [41].

Our findings sustain that negative core self-evaluation shows an association with the perceived health status and predicts health anxiety. A clinical study demonstrated that individuals with elevated health anxiety tend to be more preoccupied with the emotional impact of the health condition than individuals with normal levels of health anxiety [42]. Other results conclude that in a clinical sample (patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis, such as panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, or major depressive disorder) and healthy control sample, different score interpretations may be useful, depending on the specific context and purpose of the scientist in applying the SHAI [31,43].

Research revealed that the lower scores on the core self-evaluation subscale showed stronger associations with measures of anxiety, and depression, while the higher values proved stronger correlations with self-rated health status and strong associations in the overall mean score with the mentioned factors [44].

Previous research in the field emphasizes that gender, age, and self-rated health status are relevant in the study of health anxiety. The authors [45] found higher values of global health anxiety in women compared to men. Other research proved differences in levels of overall health anxiety, between young and older adults [46].

Concerning self-rated health status, based on an individual’s personal experience with illness can be seen as one important factor in developing further health anxiety [47]. We argue in line with the literature that assessments about self and personal health can lead to a better understanding of health anxiety [48].

In the Hungarian population, the measurements of health anxiety in non-clinical samples are very few, despite of the well-acknowledged wide presence of mental distress in the general population [49,50].

This study focuses on health anxiety-related psychological factors reported by adults, yet provides a better understanding of self-concept-determined health behavior. It serves as a good starting point for future research, such as the changes in self-evaluation and perceived health anxiety along age developmental perspective.

In our research negative core self-evaluation is associated with the perceived health status and predicted health anxiety. The construct of Self-image, with different components, such as self-evaluation and health evaluation actuate as predictors of differences in self-perceived health-related anxiety.

Revealing the resources available to an individual is relevant for the efficient use of psychosocial interventions, to achieve life goals and changes in the desired direction. For example, modalities of behavioral therapy revealed good results in decreasing the risks for negative self-evaluation and depression and anxiety symptoms [51,52].

Protective factors laying in the theory of self-determination, such as high self-evaluation, coherence, and social support, show an association with the health anxiety of individuals. Health anxiety interventions should also consider the age characteristics and health status of individuals [53].

The limitation of the study is the non-balanced dispersion of male and female participants, which might induce shortcomings in gender-related assumptions’ verification. Further, the sample presents no data about a possible medical condition, existing treatment, or other characteristics, such as family status, occupation, or educational level, which all may contribute to a difference in perceiving health-related anxiety, social support, and self-evaluation. Another shortcoming of the study is the sampling method analyzing data from a convenient adult sample.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, S.CS., M.CS. and J.B.; formal analysis, J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.CS., M.CS. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, S.CS., M.CS. and J.B. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available on request from the first and the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to informed consent compliance and ethical considerations.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Eszterházy Károly Catholic University, Eger, Hungary. By completing the online questionnaires, all participants agreed their attendance to the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Antonacci AC, Patel V, Dechario SP, Antonacci C, Standring OJ, Husk G, et al. Core competency self-assessment enhances critical review of complications and Entrustable activities. J Surg Res [Internet]. 2021;257:221–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.07.064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Strauser DR, Shen S, Greco C, Fine E, Liptak C. Work personality, core self-evaluation and perceived career barriers in young adult central nervous system cancer survivors. J Occup [Internet]. 2021;31(1):119–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09897-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Li Y, Wang Z, You W, You WQ, Liu XQ. Core self-evaluation, mental health and mobile phone dependence in Chinese high school students: why should we care. Ital J Pediatr [Internet]. 2022;48(1):28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-01217-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tian X, Huang B, Li H, Xie S, Afzal K, Si J, et al. How parenting styles link career decision-making difficulties in Chinese college students? The mediating effects of core self-evaluation and career calling. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2021;12:661600. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Crone EA, Green KH, van de Groep IH, van der Cruijsen RA. Neurocognitive model of self-concept development in adolescence. Annu Rev Psychol [Internet]. 2022;4(1):273–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-120920-023842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Koban L, Schneider R, Ashar YK, Andrews-Hanna JR, Landy L, Moscovitch DA, et al. Social anxiety is characterized by biased learning about performance and the self. Emotion [Internet]. 2017;17(8):1144–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Kammeyer-Mueller JD, Judge TA, Scott BA. The role of core self-evaluations in the coping process. J Appl Psychol [Internet]. 2009;94(1):177–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Spence SH, Rapee RM. The etiology of social anxiety disorder: an evidence-based model. Behav Res Ther [Internet]. 2016;86(4):50–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Blöte AW, Miers AC, van den Bos E, Westenberg PM. Negative social self-cognitions: how shyness may lead to social anxiety. J Appl Dev Psychol [Internet]. 2019;63(2):9–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2019.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mehrizi SHAA, Amani O, Feyzabadi AM, Kolae ZEB. Emotion regulation, negative self-evaluation, and social anxiety symptoms: the mediating role of depressive symptoms. Curr Psychol [Internet]. 2022;47(5):881. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03225-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR. Traditional views of social support and their impact on assessment. In: Social support: an interactional view [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: Wiley-Interscience; 1990. p. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

12. Haber MG, Cohen JL, Lucas T, Baltes B. The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: a meta-analytic review. Am J Community Psychol [Internet]. 2007;39(1–2):133–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9100-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Lakey B, Orehek E, Hain KL, VanVleet M. Enacted support’s links to negative affect and perceived support are more consistent with theory when social influences are isolated from trait influences. Pers Soc Psychol B [Internet]. 2010;36(1):132–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209349375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Sun P, Sun Y, Fang D, Jiang H, Pan M. Cumulative ecological risk and problem behaviors among adolescents in secondary vocational schools: the mediating roles of core self-evaluation and basic psychological need satisfaction. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021;9:591–614. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.591614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ferguson E. A taxometric analysis of health anxiety. Psychol Med [Internet]. 2009;39(2):277–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708003322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Asmundson GJ, Taylor S, Carleton RN, Weeks JW, Hadjstavropoulos HD. Should health anxiety be carved at the joint? A look at the health anxiety construct using factor mixture modeling in a non-clinical sample. J Anxiety Disord [Internet]. 2012;26(1):246–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.11.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958. [Accessed 1992]. [Google Scholar]

18. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders [Internet]. 5th ed. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

19. Olatunji BO, Etzel EN, Tomarken AJ, Ciesielski BG, Deacon B. The effects of safety behaviors on health anxiety: an experimental investigation. Behav Res Ther [Internet]. 2011;49(11):719–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.07.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Ciułkowicz M, Misiak B, Szcześniak D, Grzebieluch J, Maciaszek J, Rymaszewska J. Social support mediates the as-sociation between health anxiety and quality of life: findings from a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2022;19(19):12962. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Shishkova I, Pervichko E. Health anxiety in frequently and rarely ill younger adolescents. Eur Psychiat [Internet]. 2022;65(S1):S429–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Pilowsky I. Dimensions of hypochondriasis. Br J Psychiatry [Internet]. 1967;113(494):89–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.113.494.89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Kellner R. Functional somatic symptoms and hypochondriasis: a survey of empirical studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry [Internet]. 1965;42(8):821–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790310089012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Groen RN, van Gils A, Emerencia AC, Bos EH, Rosmalen JGM. Exploring temporal relationships among worrying, anxiety, and somatic symptoms. J Psychosom Res [Internet]. 2021;146(1):110293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Murphy KM, McGuire AP, Erickson TM, Mezulis AH. Somatic symptoms mediate the relationship between health anxiety and health-related quality of life over eight weeks. Stress Health [Internet]. 2017;33(3):244–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Santoro G, Midolo LR, Costanzo A, Cassarà MS, Russo S, Musetti A, et al. From parental bonding to problematic gaming: the mediating role of adult attachment styles. Mediterr J Clin Psychol [Internet]. 2021;9(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.13129/2282-1619/mjcp-3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Gerolimatos LA, Edelstein BA. Predictors of health anxiety among older and young adults. Int Psychogeriatr [Internet]. 2012;24(12):1998–2008. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212001329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Eslami B, Rosa MD, Barros H, Torres-Gonzalez F, Stankunas M, Ioannidi-Kapolou E, et al. Lifetime abuse and somatic symptoms among older women and men in europe. PLoS One [Internet]. 2019;14(8):e0220741. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kail RV, Cavanaugh JC. Human development: a life-span view [Internet]. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2018. [Google Scholar]

30. Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick HMC, Clark DM. The health anxiety inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med [Internet]. 2002;32(5):843–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702005822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Deacon B, Abramowitz JS. Is hypochondriasis related to obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, or both? An empirical evaluation. J Cogn Psychother [Internet]. 2008;22(2):115–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.22.2.115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kocjan J. Short health anxiety inventory (SHAI)-polish version: evaluation of psychometric properties and factor structure. Arch Psychiatry Psychother [Internet]. 2016;3(3):68–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.12740/APP/64276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Köteles F, Simor P, Bárdos G. A Rövidített Egészségszorongás-kérdőív (SHAI) magyar verziójának kérdőíves validá-lása és pszichometriai értékelése = Validation and psychometric evaluation of the Hungarian version of the Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI). Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika [Internet]. 2011;12(3):191–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1556/Mental.12.2011.3.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Komlósi VA, Rózsa S, Nagy SZ, Sági A, Köteles F, Jónás E. A vonásönbecsülés/-önértékelés kérdőíves mérésének le-hetőségei. Alkalmazott Pszichológia [Internet]. 2017;17(2):73–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.17627/ALKPSZICH.2017.2.73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Rahe RH, Tolles RL. The brief stress and coping inventory: a useful stress management instrument. Int J Stress Manage [Internet]. 2002;9(2):61–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014950618756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Konkolÿ Thege B, Martos T, Skrabski Á, Kopp M. A rövidített stressz és megküzdés kérdőív élet értelmességét mérő alskálájának (BSCI-LM) pszichometriai jellemzői = Psychometric properties of the life meaning subscale from the Brief Stress and Coping Inventory (BSCI-LM). Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika [Internet]. 2008;9(3):243–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1556/Mental.9.2008.3.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 1991;32(6):705–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Szentiványi-Makó H, Bernáth L, Szentiványi-Makó N, Veszprémi B, Vajda DB, Kiss EC. A MOS SSS-Társas támasz mérésére szolgáló kérdőív magyar változatának pszichometriai jellemzői. Alkalmazott Pszichológia [Internet]. 2016;16(3):145–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.17627/ALKPSZICH.2016.3.145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Peláez-Fernández MA, Rey L, Extremera N. Psychological distress among the unemployed: do core self-evaluations and emotional intelligence help to minimize the psychological costs of unemployment? J Affect Disorders [Internet]. 2019;256(9):627–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Tsaousis I, Nikolaou I, Serdaris N, Judge TA. Do the core self-evaluations moderate the relationship between subjective well-being and physical and psychological health? Pers Indiv Differ [Internet]. 2007;42(8):1441–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Pujol-Cols L, Lazzaro-Salazar M. Psychological demands and health: an examination of the role of core self-evaluations in the stress-coping process. Psychol Stud [Internet]. 2020;65(4):408–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-020-00569-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kehler MD, Hadjistavropoulos HD. Is health anxiety a significant problem for individuals with multiple sclerosis? J Behav Med [Internet]. 2009;32(2):150–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9186-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Österman S, Axelsson E, Lindefors N, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Hedman-Lagerlöf M, Kern D, et al. The 14-item short health anxiety inventory (SHAI-14) used as a screening tool: appropriate interpretation and diagnostic accuracy of the Swedish version. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2022;22(1):1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04367-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Zenger M, Körner A, Maier GW, Hinz A, Stöbel-Richter Y, Brähler E, et al. The core self-evaluation scale: psychometric properties of the german version in a representative sample. J Pers Assess [Internet]. 2015;97(3):310–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2014.989367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. MacSwain KLH, Sherry SB, Stewart SH, Watt MC, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Graham AR. Gender differences in health anxiety: an investigation of the interpersonal model of health anxiety. Pers Indiv Differ [Internet]. 2009;47(8):938–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Gerolimatos LA, Edelstein BA. Anxiety-related constructs mediate the relation between age and health anxiety. Aging Ment Health [Internet]. 2012;16(8):975–982. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.688192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Abramowitz JS, Braddock AE. Psychological treatment of health anxiety and hypochondriasis: a biopsychosocial approach [Internet]. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe & Huber; 2008. [Google Scholar]

48. Asmundson GJ, Abramowitz JS, Richter AA, Whedon M. Health anxiety: current perspectives and future directions. Curr Psychiat Rep [Internet]. 2010;12(4):306–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-010-0123-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Kosic A, Lindholm P, Järvholm K, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Axelsson E. Three decades of increase in health anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis of birth cohort changes in university student samples from 1985 to 2017. J Anxiety Disord [Internet]. 2020;71(1):102208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Eurostat. Do you feel depressed?–Products Eurostat News-Eurostat (europa.eu) [downloaded at 12.28.2022]. 2017. [Google Scholar]

51. Csibi S, Csibi M. Az önértékelés és a megküzdés szerepe a serdülők egészségvédő magatartásában = The role of self-esteem and coping in adolescents’ health protective behaviors. Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika [Internet]. 2013;14(3):281–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1556/Mental.14.2013.3.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Bourbeau K, Moriarty T, Ayanniyi A, Zuhl M. The combined effect of exercise and behavioral therapy for depression and anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Sci [Internet]. 2020;10(7):116. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10070116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness [Internet]. New York, USA: Guilford Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools