Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Exploratory Study on the Meaning of Using Community Psychiatric Rehabilitation among Persons with Psychiatric Disabilities

Graduate Institute of Social Work, National Chengchi University, Taipei City, 11605, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Li-yu Song. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2022, 24(6), 975-988. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2022.021552

Received 20 January 2022; Accepted 20 June 2022; Issue published 28 September 2022

Abstract

This study explores the meaning of the use of community psychiatric rehabilitation (CPR) services to gain knowledge to improve services and shed more light on how to facilitate recovery. The topics explored included: the motivation for participation, perception and expectation towards CPR, the interactions with professionals in the CPR Center, and the feelings towards activities. A qualitative approach was adopted, and 30 consumers were interviewed face-to-face by using semi-structured interview guide. Data were analyzed using the open coding method of grounded theory. The consumer accounts provided information on the eight aspects of CPR services. The findings revealed that the CPR Center created a lifeworld, a friendly place similar to home with structure and activities. Professional relationship was the key change agent for rehabilitation. Most professionals adopted recovery-oriented approach to empower participants by giving opportunities and choices. The essential ingredients of this lifeworld covered rehabilitation goals, physical exercises, psychological impact, social interactions, learning, and economic gains. The services were venues for interpersonal interactions and provided structure for daily life, which helped consumers reach their rehabilitation goals and brought existential meaning to their lives. Yet, the accounts also revealed negative phenomena in the CPR center. Suggestions were made to improve services.Keywords

Mental disorders have been a common problem globally. In 2019, 1 in every 8 people, or 970 million people around the world were suffering from a mental disorder, with anxiety and depressive disorders the most common [1]. People who are exposed to adverse circumstances–including poverty, violence, disability, and inequality–are at higher risk [1]. Worldwide, mental illness affects more females (11.9%) than males (9.3%) [2]. Moreover, around 1 in 5 of the world’s children and adolescents have a mental health condition [3].

Mental disorders could cause a tremendous personal and socioeconomic burden. On the socioeconomic level, two of the most common mental health conditions, depression and anxiety, cost the global economy US$ 1 trillion each year [3]. The total cost of treatment of anxiety and depression disorders across 36 countries worldwide is estimated to be $147 billion by 2030 [2]. On a personal level, people with severe mental health conditions die prematurely – as much as two decades early. They often experience severe human rights violations, discrimination, and stigma [3]. Mental disorders could lead to disabilities. Persons with psychiatric disabilities (hereinafter called consumers) might suffer from damage in terms of functioning, a disability as to role performance, and disadvantages for social participation [4]. To assist consumers to overcome these disabilities, community psychiatric rehabilitation (CPR) programs have flourished since the 1970s and 1980s. The purpose of psychiatric rehabilitation is to help consumers to enhance their function, and to develop the skills needed for independent living, socialization, and effective life management. The objective for them is to live a satisfying life in the community with the least amount of ongoing professional intervention [4–6]. The literature has shown that CPR could bring positive results on outcomes such as recidivism, time spent in the community, employment and productivity, skill development, client satisfaction, greater autonomy, and health [7–9]. In addition, evidence shows that the use of CPR services is associated with better personal recovery [10]. Personal recovery occurs when the consumer moves beyond the role of a patient with a mental illness and regains hope, identity, meaning, and personal responsibility [1,8].

Despite the essential role of CPR for recovery, Rössler [11] mentioned that existing scientific evidence on the conformance rate with the treatment recommendations for CPR services was modest and below 50%. The reasons that consumers did not use CPR services were a lack of knowledge, negative perceptions about it, family member influence, and negative experiences while receiving such services such as a lack of participation, not feeling heard, a lack of congruence between consumer goals and the service design, and lack of professional competency [12]. Moreover, social stigma may deter consumers from using CPR services [13]. Especially in Chinese culture, consumers are often viewed as a source of shame by their parents and confined in the home [14–16]. Nevertheless, some consumers do participate in CPR despite these obstacles. What makes them participate? How do they experience the services? To date, there is limited research on consumer experiences concerning how they utilize CPR [8,17,18], particularly in Taiwan. Gaining this knowledge is essential to improve care for consumers and sheds more lights on how to facilitate recovery [8,17]. Thus, the investigator explores the experiences of consumers receiving CPR services in Taiwan. This was done to construct meaning through CPR service utilization from the personal accounts of consumers.

According to the Oxford dictionary, the definition of meaning includes: “the real importance of a feeling or an experience” and “a sense of purpose”. The Webster dictionary described meaning as “something meant or intended” and “implication of a hidden or special significance”. Thus, “meaning” may refer to the motivation and purpose (goal) to use CPR with the important components on CPR from the consumer perspective and the feelings they derived from these services.

Ramafikeng et al. [8] maintained that values, enjoyment, and choice were often associated with meaning. Individuals derive meaning from their values and use these values to make decisions when there are different options to choose from. Giving attendees too little influence over opportunities might lower their motivation [19]. A study found that fun occupations elicited the most positive moods, especially when they were mentally stimulating and were performed with other people [20].

The literature has revealed that there are some essential ingredients for meaningful CPR. Concerning the motive for participation, the need for socialization, and structured time use was the key motivating factors [8,19]. Setting a goal and a sense of hope was associated with positive rehabilitation outcomes [18]. Specifying a domain as a goal in the service plan was associated with positive rehabilitation outcomes in learning, working, physical wellness, and quality of life [21,22].

The quality of the professional relationship is a key factor for positive rehabilitation processes and outcomes. Krupa et al. [18] mentioned that the foundation of the Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) is this relationship. Being in a trusting relationship embraced consumer experiences and gave them confidence in the key worker, feeling understood, and a mutual liking of each other [17,18]. A good relationship between the consumer and the key worker is important for a successful recovery [18,23–25]. Rehabilitation staff may be the only key attachment figure in some consumers’ lives and this relationship could provide a secure base to promote development focused on optimal functioning [26]. Nevertheless, a relationship without structure and the possibility to participate in decision-making is not sufficient on its own [18].

Having a meaningful everyday activity and feeling productive have been repeatedly shown to be essential for recovery and enhance the perception of meaning in the consumers’ life. The day centers provide opportunities to earn money and learn new things [19]. Participation in CPR also enhances a sense of self, including increasing a sense of self-understanding and attaining new perspectives [17]. CPR helps consumers by promoting community adjustment, such as meeting daily challenges, negotiating their illness, interventions in response to serious challenges, promotion of growth and change, becoming part of the community, and overcoming poverty [18].

In sum, the synthesis of existing literature has revealed that there are some essential ingredients for CPR to provide positive outcomes, including the motivation for rehabilitation, the quality of professional relationships, the need for socialization and structured time use, a sense of being part of a community, self-understanding, gaining new perspectives, adjusting to community life, the importance of participation, learning new skills, and participating in meaningful activities.

In Taiwan, the Ministry of Health launched CPR policy and services in 1985. They defined CPR services to include halfway houses, shelter workshops, community rehabilitation centers, and home care [27]. Over the years, the rehabilitation capacity has consistently been below the estimated need and is characterized as underutilized. For example, there were an estimated 63,727 consumers (about 70% of the PSMI population) living with their families, and yet all the rehabilitation facilities combined could serve only 9449 consumers [28]. As regards underutilization, the rate of CPR service utilization ranged from 67.77%–72.76% for existing service capacity from 2016–2019 [29]. This revealed that some consumers with rehabilitation needs had needs unmet by the service. The exploration of the experiences and the constructed meaning of using the CPR services in Taiwan may offer important references for nonusers, help improve existing programs, and further enhance recovery.

This study was the second part of a two-year study (from 2015–2017) on the community psychiatric rehabilitation model in Taiwan. The investigator adopted a qualitative approach to capture the comprehensive experiences and reach a deep understanding as to the feelings and interpretations of consumer [30,31]. The focus was on descriptive analysis and interpretation of the results. The key points in question covered the motivation for participation, perception and expectation towards CPR, the interactions with professionals in the CPR center, and the feelings towards activities. This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Chengchi University in Taiwan for quality and research ethics (record number: NCCU-REC-201505-I014; approval date: 20 July 2015).

The community rehabilitation center in Taiwan is a facility that is like outpatient treatment in the United States. The center provides case management services, social and recreational activities, occupational therapy, vocational training, and sheltered workshops. Based on the information provided by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan, there were 44 CPR centers in the community run by a small nonprofit organization or an association. Of the 44 centers, 32 agreed to collaborate with the investigators. More detailed information concerning the recruiting of participating agencies has been published in another article.

Participants were recruited from community psychiatric rehabilitation centers in Taiwan. Purposeful sampling was utilized and the criteria for the selection of participants were as follows: 1) consumers must have a severe mental illness (SMI) other than substance abuse, personality disorder, or dementia due to any cause; 2) consumers must have been hospitalized at least once since the onset of mental illness to further ensure they did have an SMI; 3) consumers must have used the services at the center for at least three months; and 4) they agreed to participate in the study. The selection of interviewees was based on the consideration of willingness, diversity, and conceptual saturation, meaning that the data could reflect the comprehensiveness of the experiences concerning the utilization of CPR services. Each agency was asked to recommend potential interviewees.

Research assistants conducted all face-to-face interviews with the interview occurring at the agency during the day. The participant’s case managers introduced the research assistants to the participants to help establish trust with them. The assistants all had been equipped with the knowledge on qualitative research approach through the courses at the university and the training sessions. A training session was conducted by the investigator to familiarize the assistants with the interview guide. Each interview lasted from 31–72 min and was recorded using both a tape recorder and a cell phone. Each participant was given a voucher (worth USD 16.67) for a convenience store as payment for participation.

An interview guide was designed by the investigator. It was finalized through a test interview and discussions with colleagues and the participating agencies. The participants were asked the following questions: 1. What makes you come to this agency? 2. What did you know about the agency before you join it? 3. What do you expect to gain from the rehabilitation? 4. How do you think of the professionals in the agency? 5. How do you describe your relationship with professionals here? 6. Please select the main professional who is important to you and describe your feelings towards him/her; 7. What impressed you most when you interacted with this professional? 8. What are the main activities you participate in? and 9. How do you think of the activities?

Grounded theory was adopted to process the data. It is “a qualitative research method that uses a systematic set of procedures to develop an inductively derived theory about a phenomenon” [32]. This approach pursues generalizations by making comparisons across social situations [33]. Grounded theory can also be used as a data processing and analysis method by comparing incidents applicable to each category and integrating categories and their properties [34]. The purpose of this study was to explore the meaning inducted from the accounts of CPR service users. The data process scheme of grounded theory is suitable for this purpose.

The script of each interview was transcribed verbatim into dialogic text. The procedure of data analysis began with open coding and conceptual labeling based on the grounded theory [32]. Then, the open coding was compared across participants to extract similar and different properties and themes. The analyses were conducted manually without using any software. Each interviewee was assigned a code. For example, C4-1-1 means consumer #1 from agency #4 and page 1 on the transcript.

To establish the trustworthiness of the analysis, some feasible activities were conducted based on the suggestions of Lincoln et al. [34]. The creditability of the analysis was ensured through the prolonged engagement with the consumers at the agency. The interviewers were introduced by professionals to help the establish rapport. Face-to-face interviews enabled the interviewers to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon through observations while at the agency. The coding was sent back to each participant for member checking (the participants) to ensure both creditability and confirmability. The initial open coding was performed by a research assistant, checked by another research assistant, and then further reviewed by the investigator to ensure confirmability. The interviewers spent some time making observations in the centers after the interview, which enhances the dependability of the analysis. The investigator provided a detailed description in terms of the research process and results for the readers to make judgments concerning its transferability.

As a result, 30 consumers were willing to be interviewed. The in-depth interviews generated rich accounts from the participants. Eight aspects relevant to meaning are depicted in this section: the motivation for participation in CPR, knowledge of the CPR center, rehabilitation goals, the views towards professionals, professional relationships, feelings towards professionals, main activities participated, and feelings towards these activities. The details are described as follows. Due to limited space, only a few narratives are presented for each theme.

4.1 The Motivation for Participation in CPR

There were six major reasons that the participants joined the CPR program. First, 22 participants were referred by professionals such as a psychiatrist, nurse, and social worker, as well as the personnel of other rehabilitation agencies or city government. Second, 13 participants participated in CPR because of family members’ expectations. The family hoped that the participants could find the center of their lives, find a job, or make an adjustment after being discharged from the hospital. Third, 8 participants came to the CPR center to find a place to be, seek support, and to avoid conflict with family members, loneliness, and boredom. Fourth, 4 participants used the services because of the introduction of ex co-workers or peers. Fifth, mental health conditions and family situations made 6 participants feel that they need to make changes or work more on self-improvement. They participated in the activities to prevent themselves from deterioration, join sheltered work to ease financial pressure, and find a place that is accepting. For example, C18–1 felt the deterioration of his/her psychiatric condition and decided to face it; C16–1 no longer needed to take care of his/her mother so she could start a new journey of her own. Sixth, 3 participants came to this particular center because it was close to their home.

‘I had psychiatric disabilities and had no job then. I stayed at home idled. My mom told me to join the (CPR) center and to give it a try.’ (C2-2-1)

‘There was no one else at home. I felt lonely. He referred me to join X (center). I feel very happy here.’ (C25-2-1)

4.2 Knowledge about CPR Center

There were four categories of understanding among participants about the CPR center before they received the services: an agency to help participants with community living, a placement like a day hospital or sheltered workplace, a vocational rehabilitation agency, and limited knowledge about the center. First, 6 participants understood that the CPR center provided services to help them with medication, remain stabilized, learn skills for daily living, and have a structured life. Second, 3 participants thought the CPR center was similar to a day hospital, a place for people with psychiatric disabilities, and a sheltered workplace where there was no pressure and less competition. Third, 7 participants focused on work and thought that the CPR center provided work opportunities, vocational training, and employment referrals. Fourth, 16 participants did not have a clear idea of what the CPR center was for before joining the program. Professionals or family members had not informed them of the purpose and content of the CPR services. C17 mentioned that he/she was worried that he/she might be deceived.

‘It is a place to provide persons with psychiatric disabilities with training for daily living.’ (C20-2-1)

‘This place is like the day hospital I used to go. You would have a normal life there. They told me that here is simpler than the day hospital, so here I am.’ (C31-2-1)

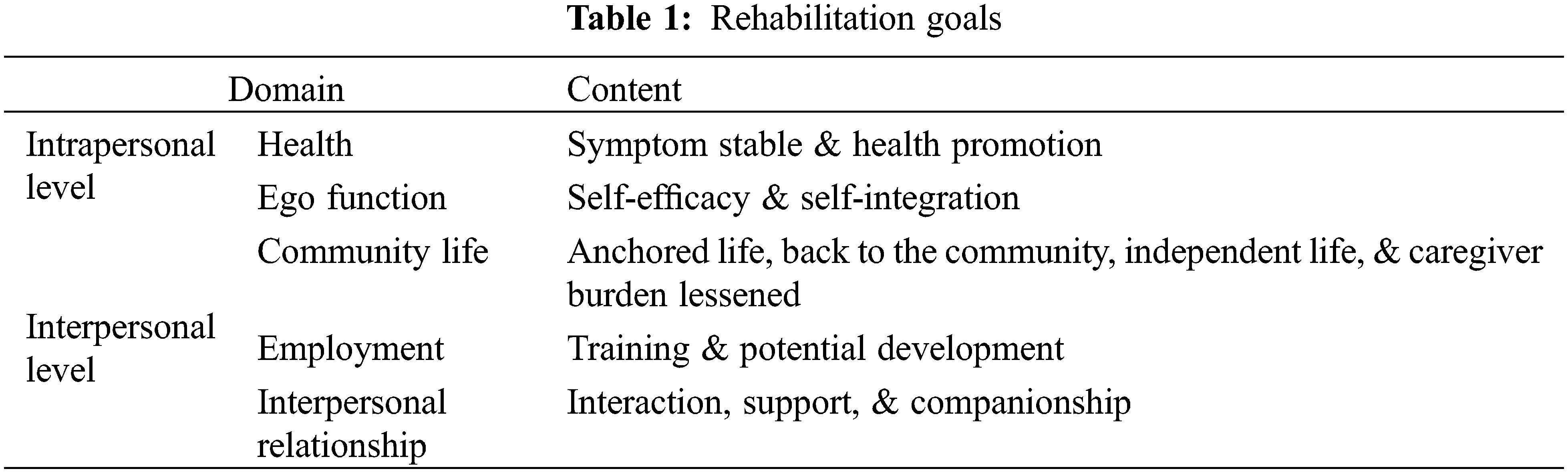

The participant rehabilitation goals included five domains: health, ego function, community life, employment, and interpersonal relationship (Table 1). The first two are related to intrapersonal goals. First, 15 participants’ goals were related to health, including mental and physical health. They like to remain stable in mental health conditions, avoid re-hospitalization, and get back to normalcy. They also wanted to improve their physical health, such as sleep quality, stamina vitality, etc. Second, 6 participants’ goals were related to ego function, including self-efficacy and self-integration. They liked to increase knowledge through various courses, improve emotional management, and work efficiency.

‘I expect that I could regain normalcy, even better than I used to be. Because I remember even when I was normal…I felt so painful inside of my heart…I hope this time I can make a good adjustment, have a good rest, and resolve the pain.’ (C16-2-3)

‘I expect myself to keep up with the outside world… What I expect is that I can live a life with dignity.’ (C18-1-3)

The other three domains were related to interpersonal goals. First, 11 participants focused on enriching community life. They mentioned that through CPR they could gain the center of their lives and have social interactions, learn new things, and enrich their lives. In addition, they wanted to learn practical skills so that they could live independently and lessen the burden on their caregivers. Second, 21 participants had employment-related goals. They wanted to have some earning through shelter work in the center. Through vocational training, they would like to have a better job or competitive job. Some hoped to reach financial independence. Third, 11 participants emphasized interpersonal relationships. CPR centers provided them the opportunity to interact with other people. They wanted to improve interaction skills, make new friends, have fun with peers, gain support, and, hopefully, have an intimate relationship.

‘The reason that I come here is hoping that I can have a place to learn things. Because you won’t feel bored when you are learning, and you will feel happy.’ (C20-1-6)

4.4 The Views towards Professionals

Most participants held positive views towards professionals at the CPR center in two domains: recognizing professionals’ effort and professionals assisting participants on rehabilitation. First, 25 participants expressed positive comments on professionals about their work attitude, ethics, and professional skills. They mentioned that professionals are good listeners, with various professional skills, and provide accessible services, work hard, are patient, capable, and emotionally steady, actively planning for them and having a good working attitude, being a person with integrity, and acting as a role model. Additionally, professionals could appreciate participants’ strengths and provide adequate assistance. Professionals actively engaged with participants with a good attitude, which made participants feel close to professionals.

‘The workers here are very amiable. They need to be very patient so they can work with people like us. I think that they did it with love. They actively design activities for us.’ (C2-1-2)

Second, 18 participants mentioned that professionals assisted participants on rehabilitation including helping them with community living, providing guidance to rehabilitation, and providing psychosocial education for caregivers. Professionals encouraged participants to participate in community activities, provided them suggestions on daily life problems, and assisted them in managing health and emotions, among others. Participants thought that professionals encouraged them to participate in various competitions, provided the training and work opportunities, guided them to think about what they wanted and how to get there, and helped them with a democratic approach and warm attitude.

‘Professionals could address my difficulties well. They provide the help that I need. They did not get away from the theme or handle it hastily.’ (C16-2-3)

‘They (professionals) won’t solve the problem for you. They guide you to think about it and then assist.’ (C15-1-1)

Yet, 6 participants mentioned the negative side of professionals. The complaints were related to professionals’ work attitude, approach, and skills. C6 thought that professionals’ kind attitude could not push him/her to change. C18 commented on the turnover of the workers in the center. New workers were not as helpful as more experienced ones. He/she thought that the most important ability was to understand participants not just using theory. C19 mentioned that professionals did not handle well the troublemakers in the center.

‘It is useless. He/she still comes to the center…The worker should call his/her parents. He/she shouldn’t behave this way, coming and going as he/she wishes, throwing things at people… It is so scary!’ (C19-2-7)

Some felt that professionals were too busy to interact with participants.

‘The workers are so busy… If participants were not aware that workers were busy and went to talk to them, then workers would be very unhappy. So, participants usually don’t talk to workers much.’ (C31-2-15)

Participant accounts revealed four types of professional relationships: as a family member, like a friend, like a friend and a teacher, and just a professional. First, 6 participants thought that professionals were like family members to them. Professionals understood them, even better than their true family members.

‘I think that they (professionals) understand me more than my family members. They know how to get along with me… My family members are good to me, too, but they don’t know how to treat me… They know how to treat us…. They are more patient. We have less chance to be hurt by their words.’ (C2-1-3).

However, just like family members, they expressed true feelings to each other, which might create conflicts. Second, 15 participants thought professionals were like friends or peers to them. They had fun together, shared information and experiences, and treated each other for food, etc. Professionals interacted with participants in a natural way. Just like C20–2 said: ‘We are like friends, equal…. When I have some wrong ideas, thoughts, or doubts, I’ll ask them. They would give me useful advice.’ Third, 3 participants thought that professionals were like a friend and a teacher. Sometimes, professionals acted as a friend. However, they have professional knowledge and play a coaching role. Participants usually treat professionals as ‘teachers’. Fourth, 12 participants viewed professionals as just a professional. Some did not ask for help from professionals for personal matters because they relied on their own religious beliefs to solve problems, or because they were shy. Some centers focused on vocational training; thus, the professionals acted more like managers. Some professionals also acted as a coach and guide for daily living, work, and problem-solving.

‘Our relationship is okay, but not like friends. We maintain a professional relationship. They care for us, and they are teachers, too. We are students who come here to learn. And I am also a patient.’ (C16-2-4)

4.6 Feelings towards Professionals

Most participants held positive feelings towards professionals, including being valued by professionals and feeling happy during the interaction, acknowledging the helpfulness of professionals’ service, and interacting smoothly. First, 14 participants showed appreciation for professionals since they felt the warmth, kindness, and patience from them. They used to be the ones to be blamed, judged, or neglected by others. Nevertheless, they felt being valued and cared for attentively by professionals. Based on this good relationship, some participants felt it was enjoyable to be with professionals. Professionals were accessible and kind, which made participants feel included. Some felt that participants and professionals could interact on equal footing without pressure. They cherished so much the time they spent together. Second, 17 participants acknowledged the helpfulness of professional services in the following. Participants thought that the professional services were effective in several ways, such as medication, health behaviors, family communication, self-reflection, problem-solving, emotional management, and stability to participate. Professionals facilitated consumer autonomy by assigning responsibility as a leader, offering opportunities for learning vocational skills, and coaching participants for independent living. Due to psychiatric disabilities, participants often experienced over-protection or deprivation of their right for making decisions. Thus, they felt quite impressed by the endowment of responsibility and opportunity offered by professionals. Some participants commented that professionals were competent with great credentials and could empathize with the hardship of the professionals’ work. Participants mentioned that professionals provided them with food, drink, cash, or voucher, among others as a reward for positive behaviors or achievements. Third, 6 participants felt that they had a close relationship with professionals. They could disclose their inner feelings even dreams with professionals. They chatted and made jokes with each other. Furthermore, the enjoyment could turn into a romantic fantasy toward a particular professional, such as C6–1.

‘I think that workers are all very amiable. They helped us solve all the problems. And they work so hard, which made me feel being valued.’ (C15-1-3)

‘(I was assigned) the role as the foreman…. I like it. Being a foreman, I should work fast, cannot be slow.’ (C19-1-11)

Nevertheless, 6 participants had negative feelings towards particular professionals as well. Professional’s authoritative or emotional behaviors, such as being angry or accusative, would distance participants from them. In addition, some participants (C19–2 & C20–1) did not like to be asked about or to talk about personal matters. They could not be candid on these issues. Before the trust relationship is built, consumers could be afraid of the professional.

‘When I just came here, I was afraid of offending him (smile) and afraid of offending others. I was not that familiar with him. I just came here then.’ (C16-1-8)

4.7 Main Activities Participated

Participants mainly participated in three major types of activities: physical activities, vocational rehabilitation, and community participation. Various physical exercises were taking place in the agencies, such as football, basketball, yoga, walking, or physical stretching, among others. Eight participants felt that they benefited from these physical activities. C15–1 mentioned he/she enjoyed doing exercises with peers. He/she said: ‘I met many classmates here. We do exercises together. I am very happy to share my exercise experiences with them.’ (C15-1-4). The second type was comprised of three categories of activities: vocational training (16 participants mentioned it), social and occupational training group (20 participants), and administrative tasks (4 participants). First, the vocational training in Taiwan is for participants to learn work skills in various fields, such as baking, cleaning, handcrafts, farming, or accounting, among others. Participants do small jobs and earn a salary. They could choose which type of work they like to participate in. Those with better performance were assigned the role of a foreman. Some might join the working group in the community later. Second, the social and occupational training group enhanced participants’ functioning in daily life. The activities covered cooking, painting, gardening, handcraft, and psychosocial education, etc. The social part focused on emotional management and interpersonal social skill courses. Third, some participants played the role of helping the operation of the agency, such as checking on the equipment, assigning work, or monitoring the work operation, among others. They usually were the ones with better functionality. Their participation could also further enhance their attention level.

‘I play a role in the self-governing committee. There are others on the committee. Before the committee is formed, I did most work. After the committee is formed, we share the work. If we run into problems, we go to XX (a professional) for help.’ (C18-1-7)

There were two types of community participation: outdoor activities (10 participants mentioned) and recreational activities (6 participants). First, most agencies facilitated participants to mingle with the outside world through participating in group competitions (such as sports, choir, or dancing, among activities), one-day or half-day trips, mountain climbing, etc. Most participants enjoyed this type of activity. C15–2 mentioned that: ‘We planned a half-day trip by ourselves. We decided where we wanted to go, how to get there, how much money we needed.’ (C15-2-3). Some agencies arranged participants to do voluntary work, such as cleaning a park. Second, participants would get together and do leisure activities, such as playing chess, doing handcraft, painting, shopping, or chatting. They are for relaxation and elevating interpersonal interactions and the quality of life.

4.8 Feelings towards Activities

Participants had both positive and negative feelings toward the activities they participated in. The positive feelings were related to the rapport built up among participants, increases in income, enhanced physical and mental health, enhanced confidence, had a good atmosphere that was inclusive, and they acquired information. First, 11 participants mentioned that they enjoyed the interactions with peers. They experienced the peace of mind, found peers who shared the same interest, gained friendship, and helped each other. The help from peers helped the rehabilitation process. Second, 7 participants mentioned that through doing shelter work or attending vocational training that they could earn some money and buy the things they need. That is important, as C26–1 said: ‘Spent my own money.’ C31–2 said: ‘Let others have a chance to recognize our products and make some money.’ Third, 12 participants felt that the activities helped maintain and enhance their health and function. Some felt that the activities made them find a center and their lives become more fulfilling. As C15–1 said: ‘In here I practiced the teaching of Buddhism, such as not being angry with others, being forgiving.’ Fourth, 12 participants mentioned that they received positive feedback and acquired confidence in doing these activities. They learned new things through trial and error but gradually gained proficiency. They also experienced growth, as C18–1 said: ‘I trust myself and others more…. Just do it and you will see the difference in yourself…’ Fifth, 16 participants praised the activities. They thought the activities are interesting, flexible, inclusive, exciting, and meaningful. They enjoyed the classes immensely. They also felt being respected and trusted by the professionals. C31 felt that the rehabilitation center is indispensable to him. The activities keep him/her from being over-focused on themselves. C2–1 mentioned: ‘I love to come here. I don’t like a holiday.’ Sixth, 6 participants mentioned that they were happy to learn new things. These activities are useful and practical in daily living.

Some participants expressed negative feelings toward the activities. The reasons included activities not interesting, unsatisfied with peer interactions, or the pressure from vocational training. First, 5 participants mentioned that part of the activities were not interesting or dull. For example, C4–2 said he/she does not like static activities. Second, 5 participants’ negative feelings stemmed from problems with peer interactions, such as boundary issues, interruption of other peers during class, or peers being passive or not emotionally stable. These problems had deterred participants’ willingness to come to the center. Third, 4 participants expressed the pressure from vocational training. Long working hours, low salary, and heavy workload resulted in physical fatigue, negative emotions, and limited time left for other things.

5.1 The Meaning of Psychiatric Rehabilitation

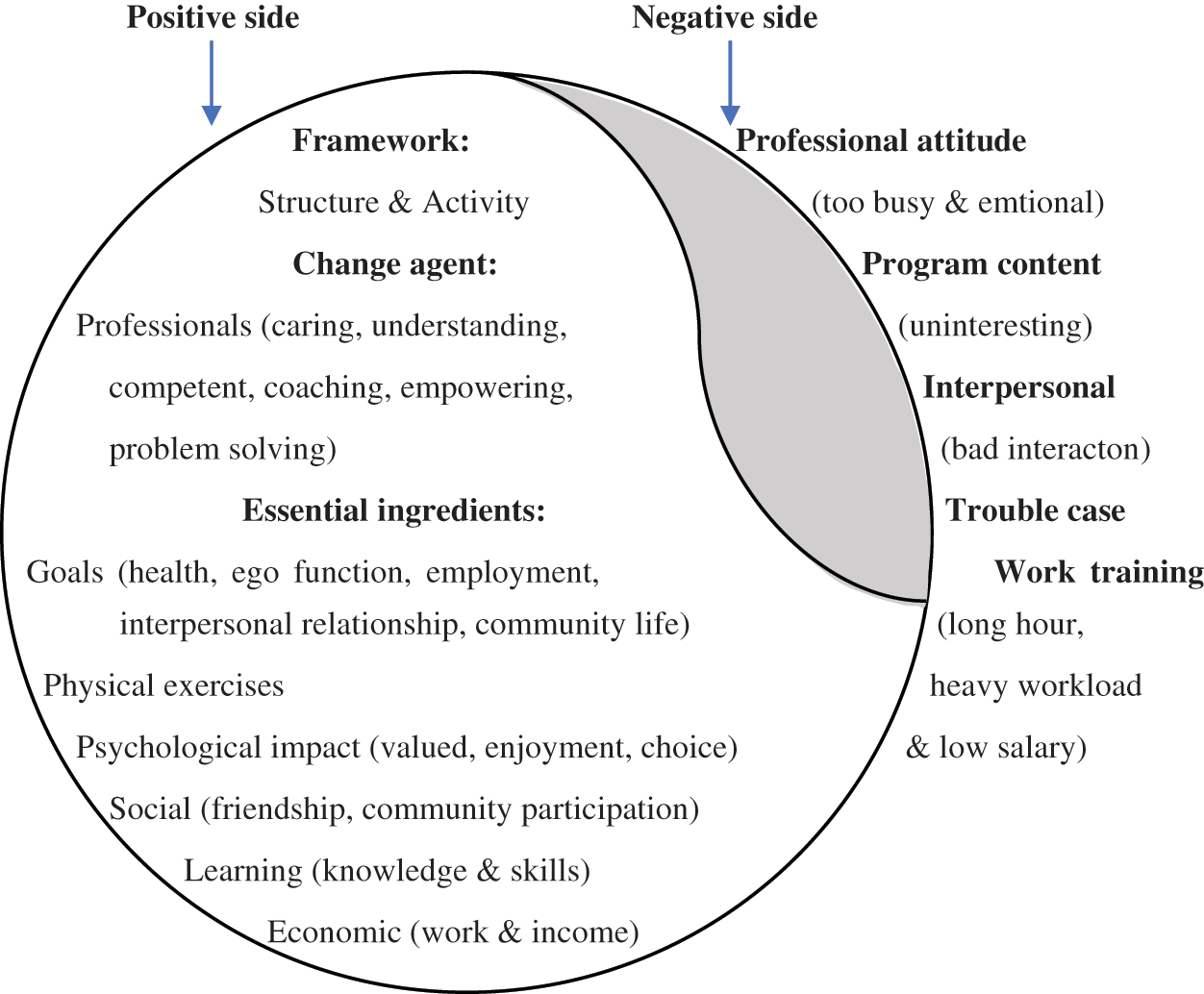

The accounts of the participants revealed that the CPR center created a lifeworld where for some participants it was like a home, for some it was a place to interact with people and make friends, for some it was a place for learning, and for some, it was a place for working and making money. In the lifeworld, participants found a center of their life through the structure of daily operation and the activities arranged by the CPR center (Fig. 1). The professionals played an essential role as change agents. Most participants appreciated the professionals’ good attitude, efforts, and assistance to rehabilitation. Professionals were portrayed as caring, understanding, and competent. They played roles as a coach, a teacher, a friend, or even like a family member. Most participants had a trusting relationship with professionals and felt close to them. As Krupa et al. [18] mentioned the foundation of the ACT is the relationship. Through the relationship, the existence of the participants was assured. For some participants, the trusting and warm relationship facilitated them to continuously come to the center. It became an indispensable part of their life. The findings confirmed the importance of professional relationships to rehabilitation and recovery as mentioned in the literature [10,18,23–25]. Based on participants’ experiences, most professionals adopted a recovery-oriented approach as outlined by Russinova et al. [35] on facilitating participation in activities, discussing goals and ways to achieve them, providing learning opportunities, and using participants’ strengths. This approach empowered participants because they were given opportunities and choices. They were viewed as a person instead of a patient.

Figure 1: The lifeworld of community psychiatric rehabilitation center—Striving for recovery

Fig. 1 outlines the essential ingredients that are demonstrated or embedded in daily activities. These ingredients were delivered in daily encounters among participants, peers, and professionals. The white area represents the positive side of the life world. The five aspects of participants’ goals are related to recovery. Health and ego function have to do with the recovery process; community life, interpersonal relationship, and employment are components of the recovery outcome [36]. Practically, the participants wanted to regain normalcy and live in the community as other people. Jormfeldt et al. [17] maintained that participating in CPR could enhance a sense of self. From the perspective of symbolic interactionism, self-identity was shaped through the symbols used during the interaction with others [37,38]. Physical exercises were helpful for both health and emotionality. Psychologically, participants felt valued by professionals and were given choices. There was positive emotionality among the actors in the lifeworld, which is essential for the sustainability of interaction [37]. Socially, the participants built up friendships with professionals and peers, mutually supported each other, and had chances to mingle with society through community activities. The learning activities helped the participants gain social and occupational knowledge/skills. The sheltered work made participants feel productive and capable. All these ingredients might help the participants reconstruct their self-identity and recovery.

Despite that most consumers expressed positive experiences with the rehabilitation center, some consumers revealed the negative phenomenon of this lifeworld (the gray area in Fig. 1), including the bad attitude of professionals, program content not being interesting, having bad interactions with peers, disruption from the troubling case in the center, and work training being too long but earn too little money. Professionals’ emotional behaviors might have to do with the heavy workload, inadequate coping, lack of knowledge and skills, or lack of supervision. It might also mean that the services were not individualized enough to meet the unique needs of some consumers. Training on recovery-oriented services as well as periodic service monitoring and supervision might solve these problems. Farkas et al. [39] mentioned that there are four values of recovery-oriented services: person orientation, personal involvement, self-determination/choice, and growth potential. This study supports that the implementation of recovery-oriented services was related to the positive experiences of the participants. Concerning the program content, a mechanism needs to be constructed to periodically gather consumers’ experiences to make modifications and meet their unique needs as much as possible. Some negative feelings were related to how the interpersonal interaction problems were managed. Interpersonal issues are not easy to address as each consumer deserves the right to receive service and professionals need to remain impartial. It takes both professional knowledge and practical wisdom for it. Again, periodic supervisions are warranted to discuss these issues and define better solutions. The CPR center provides sheltered works for the participants. Usually, they are low-level work in Taiwan and result in a limited income. For the consumers who aim at earning money, the pay is too little. This is a structural problem with no easy solution. Given the structural limitation, professionals need to pay more attention to those who cannot stand the stress of long hours of work and be more flexible on schedule.

This study interviewed 30 consumers based on informed consent. In addition, the interviews were conducted in a counseling room of the CPR center. Although consumers would feel more comfortable in a familiar environment, the topics concerning the views and feelings on professionals and activities might induce social desirability and compromise the credibility and dependability of the accounts. The selection of the participants considered the diversity and narratives from the consumers provided rich information. Nevertheless, conceptual saturation could not be fully assured. Finally, despite that the participants had all came from 32 CPR centers in Taiwan and the investigator had provided the detailed content of the findings, the transferability is uncertain. Future studies are needed to further explore this subject.

This study portrays the lifeworld of the consumers at the CPR centers and the meaning derived from that. It is the first study of its kind in Taiwan. The accounts of consumers provided rich information on eight aspects that could shed further light on how to facilitate recovery. The CPR center is a place that is friendly even like a home. The services were venues for interpersonal interactions and provided the structure of daily life, which brought existential meaning to consumers and helped them move towards recovery.

Funding Statement: This study was sponsored by the Ministry of Technology in Taiwan (MOST 104–2410-H-004-147-SS2). The author is especially thankful for the consumers and professionals who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. World Health Organization (2022). Mental disorders. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders. [Google Scholar]

2. SingleCare (2022). Mental health statistics 2022. https://www.singlecare.com/blog/news/mental-health-statistics/. [Google Scholar]

3. World Health Organization (2022). Mental health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab = tab_1. [Google Scholar]

4. Anthony, W., Cohen, M., Farkas, M., Gagne, C. (2002). Psychiatric rehabilitation. Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston, MA: Boston University. [Google Scholar]

5. Bond, G. R., Drake, R. E. (2017). New directions for psychiatric rehabilitation in the USA. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 26, 223–227. DOI 10.1017/S2045796016000834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Corrigan, P. W., Mueser, K. T., Bond, G. R., Drake, R. E., Solomon, P. (2008). Principles and practice of psychiatric rehabilitation: An empirical approach. New York NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

7. Killaspy, H. (2014). Contemporary mental health rehabilitation. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry, 24(3), 89–94. DOI 10.1017/S2045796018000318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ramafikeng, M., Beukes, L., Hassan, A., Kohler, T., Mouton, T. L. et al. (2020). Experiences of adults with psychiatric disabilities participating in an activity programme at a psychosocial rehabilitation centre in the western cape. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 50(2), 44–51. DOI 10.17159/2310-3833/2020/vol50no2a6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Spaniol, L., Brown, M. A., Blankertz, L., Burnham, D. J., Dincin, J. et al. (1994). An introduction to psychiatric rehabilitation. Columbia, MD: International Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services. [Google Scholar]

10. Slade, M. (2009). Personal recovery and mental illness. UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

11. Rössler, W. (2006). Psychiatric rehabilitation today: An overview. World Psychiatry, 5(3), 151–157. [Google Scholar]

12. Moran, G. S., Baruch, Y., Azaiza, F., Lachman, M. (2016). Why do mental health consumers who receive rehabilitation services, are not using them? A qualitative investigation of users’ perspectives in Israel. Community Mental Health Journal, 52, 859–872. DOI 10.1007/s10597-015-9905-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Liegghio, M. (2017). ‘Not a good person’: Family stigma of mental illness from the perspectives of young siblings. Child & Family Social Work, 22(3), 1237–1245. DOI 10.1111/cfs.12340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cheung, F. M. (1990). People against the mentally ill: Community opposition to residential treatment facilities. Community Mental Health Journal, 26, 205–212. DOI 10.1007/BF00752396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Leung, P. (1990). Asian Americans and psychology: Unresolved issues. Professional Psychology, Training and Practice, 4, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

16. Tsang, H., Fong, C., Bond, G. (2010). Cultural considerations for adapting psychiatric rehabilitation models in Hong Kong. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 7, 35–51. DOI 10.1080/15487760490464988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jormfeldt, H., Svensson, B., Hansson, L., Svedberg, P. (2014). Clients’ experiences of the Boston psychiatric rehabilitation approach: A qualitative study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 22916. DOI 10.3402/qhw.v9.22916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Krupa, T., Eastabrook, S., Hern, L., Lee, D., North, R. (2005). How do people who receive assertive community treatment experience this service? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29(1), 18–24. DOI 10.2975/29.2005.18.24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Eklund, M., Tjörnstrand, C. (2013). Psychiatric rehabilitation in community-based day centres: Motivation and satisfaction. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20(6), 438–445. DOI 10.3109/11038128.2013.805428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ikiugu, M. N., Hoyme, A. K., Mueller, B., Reinke, R. R. (2016). Difference between meaningful and psychologically rewarding occupations: Findings from two pilot studies. Journal of Occupational Science, 23(2), 266–277. DOI 10.1080/14427591.2015.1085431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hutchison, S. L., MacDonald-Wilson, K. L., Karpov, I., Maise, A. M., Wasilchak, D. (2017). Value of psychiatric rehabilitation in a behavioral health medicaid managed care system. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 40(2), 216–224. DOI 10.1037/prj0000271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sanches, S. A., van Busschbach, J. T., Michon, H. W. C., van Weeghel, J., Swildens, W. E. (2018). The role of working alliance in attainment of personal goals and improvement in quality of life during psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Services, 69(8), 903–909. [Google Scholar]

23. Song, L. (2017). Predictors of personal recovery for persons with psychiatric disabilities:An examination of the unity model of recovery. Psychiatry Research, 250, 185–192. DOI 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hicks, A. L., Deane, F. P., Crowe, T. P. (2012). Change in working alliance and recovery in severe mental illness: An exploratory study. Journal of Mental Health, 21, 127–134. DOI 10.3109/09638237.2011.621469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Moran, G., Mashiach-Eizenberg, M., Roe, D., Berman, Y., Shalev, A. (2014). Investigating the anatomy of the helping relationship in the context of psychiatric rehabilitation: The relation between working alliance, providers’ recovery competencies and personal recovery. Psychiatry Research, 220(1–2), 592–597. DOI 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Berry, K., Drake, R. (2010). Attachment theory in psychiatric rehabilitation: Informing clinical practice. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 16, 308–315. DOI 10.1192/apt.bp.109.006809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Song, L. (1998). Community care for persons with chronic mental illness: A choice or dilemma? Formosa Journal of Mental Health, 11(4), 73–103. [Google Scholar]

28. Ministry of Health and Welfare (2018). Current psychiatric treatment resources. https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/sp-GS-113.html?Query=%E7%B2%BE%E7%A5%9E%E9%86%AB%E7%99%82%E8%B3%87%E6%BA%90#gsc.tab=0&gsc.q=%E7%B2%BE%E7%A5%9E%E9%86%AB%E7%99%82%E8%B3%87%E6%BA%90&gsc.sort=. [Google Scholar]

29. Ministry of Health and Welfare (2020). Current psychiatric agencies and service use statistics. https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/cp-3907-40352-113.html. [Google Scholar]

30. Grinnell Jr, R. (1993). Social work research and evaluation (4th ed.). Itasca, IL: F.E. Peacock Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

31. Lincoln, Y. S., Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

32. Strauss, A., Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

33. Neuman,W. L. (1997). Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

34. Lincoln, Y. S., Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

35. Russinova, Z., Rogers, E. S., Cook, K. F., Ellison, M. L., Lyass, A. (2011). Recovery-promoting professional competencies: Perspectives of mental health consumers, consumer-providers and providers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 34(3), 177–185. [Google Scholar]

36. Song, L., Shih, C. (2009). Factors, process, and outcomes of recovery from psychiatric disability—The unity model. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 55(4), 348–360. DOI 10.1177/0020764008093805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hausmann, C., Jonason, A., Summers-Effler, E. (2011). Interaction ritual theory and structural symbolic interactionism. Symbolic Interaction, 34(3), 319–329. DOI 10.1525/si.2011.34.3.319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Turner, J. H. (2011). Extending the symbolic interactionist theory of interaction processes: A conceptual outline. Symbolic Interaction, 34(3), 330–339. DOI 10.1525/si.2011.34.3.330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Farkas, M., Gagne, C., Anthony, W., Chamberlin, J. (2005). Implementing recovery oriented evidence based programs: Identifying the critical dimensions. Community Mental Health Journal, 41(2), 141–158. DOI 10.1007/s10597-005-2649-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools