| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.021452

ARTICLE

Mental Health Disorders of the Indonesian People in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Who is Vulnerable to Experiencing it?

1Research Center for Public Health and Nutrition, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jakarta, 10340, Indonesia

2Research Center for Pre Clinical and Clinical Medicine, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jakarta, 10340, Indonesia

3Bandung Health Polytechnic, Ministry of Health, Bandung, 40173, Indonesia

*Corresponding Author: Rofingatul Mubasyiroh. Email: rofingatul.mubasyiroh@brin.go.id

Received: 15 January 2022; Accepted: 13 June 2022

Abstract: The extraordinary situation related to COVID-19 makes people worry about their health, family health, work, finances, and other daily activities. This condition can lead to social unrest, which has consequences for mental health problems. This study aims to determine the mental health consequences at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. This is a cross-sectional study involving a target population aged 18 years and over who had access to electronic communication devices. An online questionnaire was randomly distributed and snowballed throughout 34 provinces in Indonesia. The study was conducted from 2 to 4 May 2020. Non-parametric and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to identify factors associated with anxiety and depression. Two thousand seven hundred forty-three participants were involved in this study, with 69.16% female. In sum, 6.92% of participants had General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scores ≥ 10 for moderate-severe anxiety symptoms, and 8.57% had Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores ≥ 10 for moderate-severe depressive symptoms. The multivariate linear regression analyses showed that the strongest factors influencing anxiety and depression were a history of mental illnesses, chronic illnesses, the group affected by layoffs or job seekers, unemployed, students, younger age group, living in a rented house, single, and female. In contrast, the lower and secondary education level seems to reduce the risk of depression compared to those with higher education levels. Anxiety and depression occur during the periods of activity restriction during the COVID-19 pandemic and are influenced by several modifiable and non-modifiable factors. There is an urgent need to emphasize vulnerable groups such as those with a history of illness, those affected by layoffs/looking for work, and the younger age group.

Keywords: General population; mental health; early-stage COVID-19; Indonesia

Taking a lesson from the history of global pandemics over the past few decades, many social impacts seem inevitable. Several outbreaks, such as the bubonic plague (black death), Ebola, legionnaires, and SARS, have unveiled psychological conditions experienced by the affected people [1]. There are three types of disasters: natural, technological, and disasters caused by violence (war). Each type of disaster has a distinct impact; generally, the effect of war is more prominent than natural disasters (Norris, 2002 and Norris, 2006). However, a natural disaster caused by biological agents that are usually invisible and unfamiliar raises the anxiety about the uncertainty of the level of exposure that someone may suffer. The impact goes beyond individuals infected–social stigma and isolation, leading to broader economic disruption [2].

The transmission process of COVID-19 in Indonesia is relatively fast; the first two positive cases were detected on March 2nd, 2020 [3], and were reported by the Gugus Tugas Percepatan Penanganan (COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force/GTPP) the next day in a press conference. In addition, through the GTTP official website on March 23rd, 2020, 579 positive cases were reported, and 49 people died due to the COVID-19 [4]. Later, the COVID-19 cases spread rapidly in several provinces in Indonesia. Efforts to prevent the COVID-19 disease transmission to the community generate mobility restrictions (physical, psychological, and economic). Then rumors spread, some sanitation products were scarce on the market, schools and workplaces were closed, and activities that gathered people together were prohibited. The adoption of new habits and the uncertainty of conditions trigger social unrest. Psychologically, changes in the environment make someone feel insecure, restless, and anxious [5]. This extraordinary situation makes people worry about their health, family health, work, finances, and other daily activities. This condition can lead to social unrest, which has consequences for mental health problems.

Psychological conditions related to COVID-19 have been described in a study conducted in February 2020 in China involving 7.236 respondents using a website-based survey which showed that the prevalence of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and sleep quality were 35.1%, 20.1%, and 18.2%, respectively [6]. Another study in Iran in March found that 9.3% of the population experienced severe anxiety, while another 9.8% experienced very severe criteria [7]. Therefore, this study aims to determine the mental health consequences at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia.

The study was a cross-sectional study conducted on the general population in Indonesia. The target population was Indonesians aged 18 years and over who had access to electronic communication devices. This study has been approved for an ethical permit by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Health Research and Development (Badan Litbangkes), Indonesian Ministry of Health with number LB.02.01/2/KE.326/2020 on 27 April 2020. The study was conducted from 2 to 4 May 2020–a month after implementing large-scale social restrictions in several provinces.

The data was collected through an online questionnaire which was randomly distributed and snowballed via WhatsApp group and Facebook to selected contact persons in all 34 provinces in Indonesia. Participation in this study was voluntary, there was no coercion, and participants might decide to stop when completing the questionnaire. This provision was clearly stated at informed consent at the beginning of the online survey page. The questionnaire consists of a listed question with answer choices. The survey screen display was created per question topic per page. Then the participants might click on the answer choices that represent their condition. Respondents might change the selected answers before the questionnaire was submitted.

Anxiety and depression were used as the outcome variable. Anxiety disorders were measured using the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire. The respondent must answer seven questions to describe their conditions in the last two weeks preceding the survey. Each question consists of four answer scales (never; several days; more than a week; almost every day). A score was given for each question answered, ranging from 0 (never) to a score of 3 (nearly every day). Then, the scores of the seven questions were added up and categorized into normal (score 0–4), mild anxiety (score 5–9), moderate anxiety (score 10–14), and severe anxiety (score 15–21) [8]. Using the same instrument and online research design during the COVID-19 period in Indonesian general population, the GAD-7 instrument has very good internal reliability (α = 0.81) [9]. On the sample group of Indonesian non-health workers during the COVID-19 period also showed very good internal reliability (α = 0.878) [10].

Depressive disorders were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). There were nine questions that the respondents had to answer to describe their condition in the last two weeks before the survey. Each question consists of 4 answer scales (never; a few days; more than a week; almost every day). A score was given for each question answered, ranging from 0 (never) to a score of 3 (nearly every day). Then, the scores of the nine questions were added up and categorized as depressed if the score ≥ 10 [11]. Using the same instrument and online research design during the COVID-19 period in Indonesian general population, the PHQ-9 instrument has very good internal reliability (α = 0.85) [9].

Socio-demographic data includes gender; age (based on last birthday); education (graduated education, which was marked by the previous certificate obtained); occupation (full-time activity); current marital status; homeownership status; residential zoning area when the survey was conducted (the zoning system of COVD-19 was based on case severity: green (1–100 cases), yellow (101–500 cases), orange (501–2000 cases), red (>2000 cases); history of mental illnesses (based on whether a doctor advised the respondent to referred–either offline/online–to a psychologist/psychiatrist in the period before the outbreak occurred); chronic diseases (based on whether the respondent has ever been diagnosed with a chronic illness by health providers in the form of diabetes mellitus/heart disease/hypertension/stroke/chronic bronchitis/asthma/cancer).

The data analyses were performed on STATA version 14–the software was under the National Institute of Health Research and Development (Badan Litbangkes), Indonesian Ministry of Health. The analyses were only carried out on a completed questionnaire and data that met the inclusion criteria. Characteristics of participants are shown using a descriptive distribution, including the respondent’s history of psychiatric illness and non-communicable diseases (NCDs). A normality test was performed on anxiety and depression scores using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The test results showed that the distribution of anxiety and depression scores was not normal, so the analysis was carried out using non-parametric analysis. Non-parametric univariate analyses–Mann-Whitney (for variables with two categories) and Kruskal-Wallis (for variables with >2 types), were used to assess the significance of the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistically significant variables were included in the multivariate linear regression model for further investigation. Two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

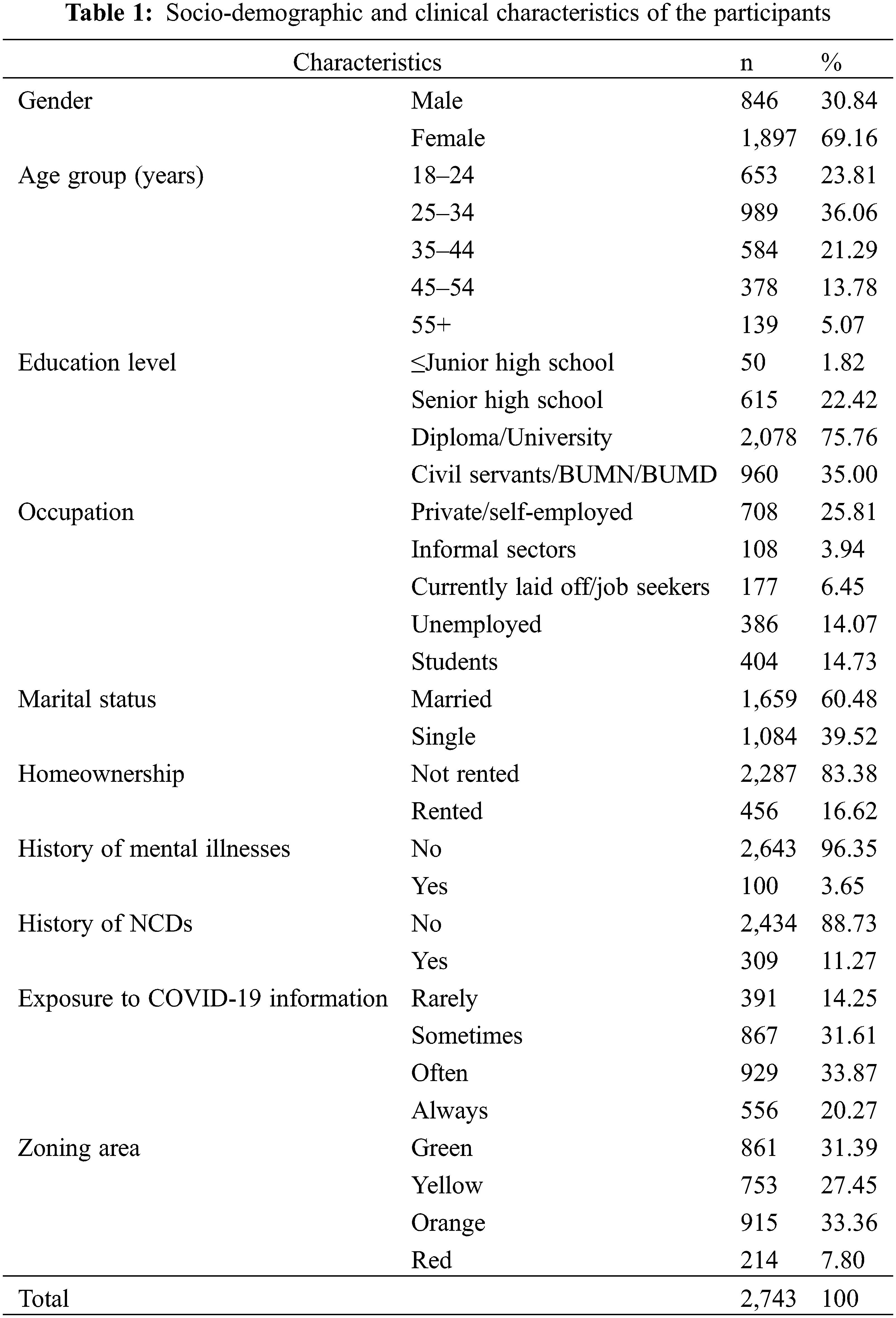

3.1 Characteristics of Participants

Of 2,743 participants, most of them were women (69.16%). Most of the participants were young adults aged 25–34 years (36.06%). Our survey was also dominated by the higher education group who have completed tertiary education (diploma and bachelor’s degree) with 2,078 participants (75.76%). The participants ranged from civil servants (35.00%) to private and self-employed workers (25.81%). More than half of the participants were married (60.48%), and most of them lived in their own house/family/office/not rented house (83.38%). A small proportion of participants had a history of mental illnesses (3.65%). Furthermore, 11.27% of the participants had a history of non-communicable diseases in the past year. The behavioral patterns of participants in accessing information related to COVID-19 varied at the beginning of the pandemic. The majority of the participants reported that they often accessed the information (33.87%), followed by sometimes (31.61%) and always (20.27%). Participants also came from various COVID-19 zoning areas, ranging from orange (33.36%), green (31.39%), yellow (27.45%), and red (7.80%) (Table 1).

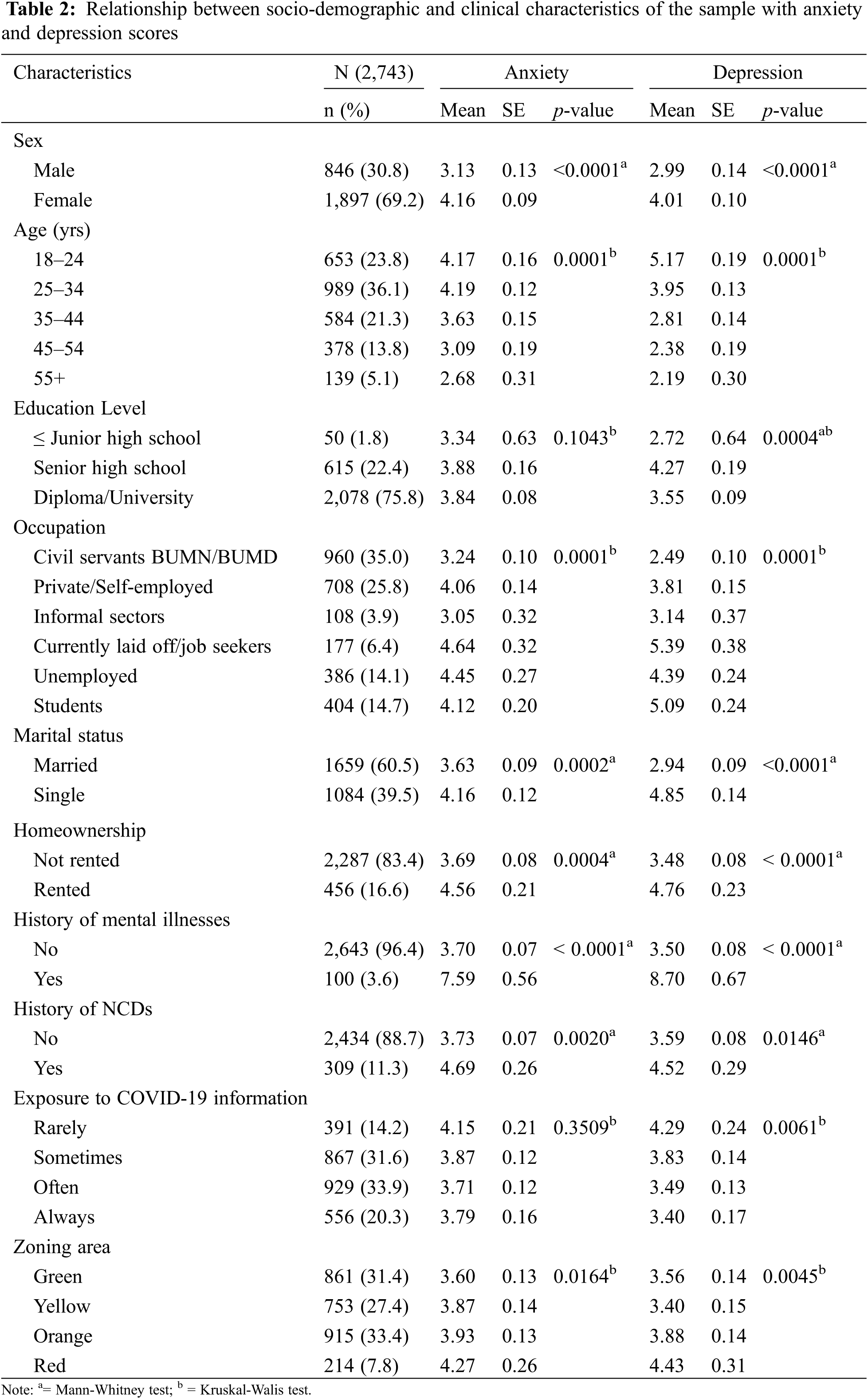

3.2 Relationship between Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample with Anxiety and Depression Scores

The participants had a mean score of anxiety and depression of 3.84 and 0.09, respectively. The anxiety scores were significantly higher among females, the young age group, unemployed or laid off/job seekers, students, single, lived in a rented house, had a history of mental illnesses and NCDs, and had high-risk COVID-19 zoning areas. Depression scores were significantly higher in those who were female, were in the young age group, had higher education, were unemployed or had been laid off/job seekers, students, had never been married, lived in a rented house, had a history of mental illnesses and NCDs, were rarely exposed to information about COVID-19, and were in the high-risk COVID-19 zoning area (Table 2). According to the anxiety score, 28.26% of the participants had mild anxiety, 4.30% were moderate, and 2.62% were severe. Meanwhile, in terms of depression, 21.84% had mild depression, 5.40% were moderate, and 3.17% were severe.

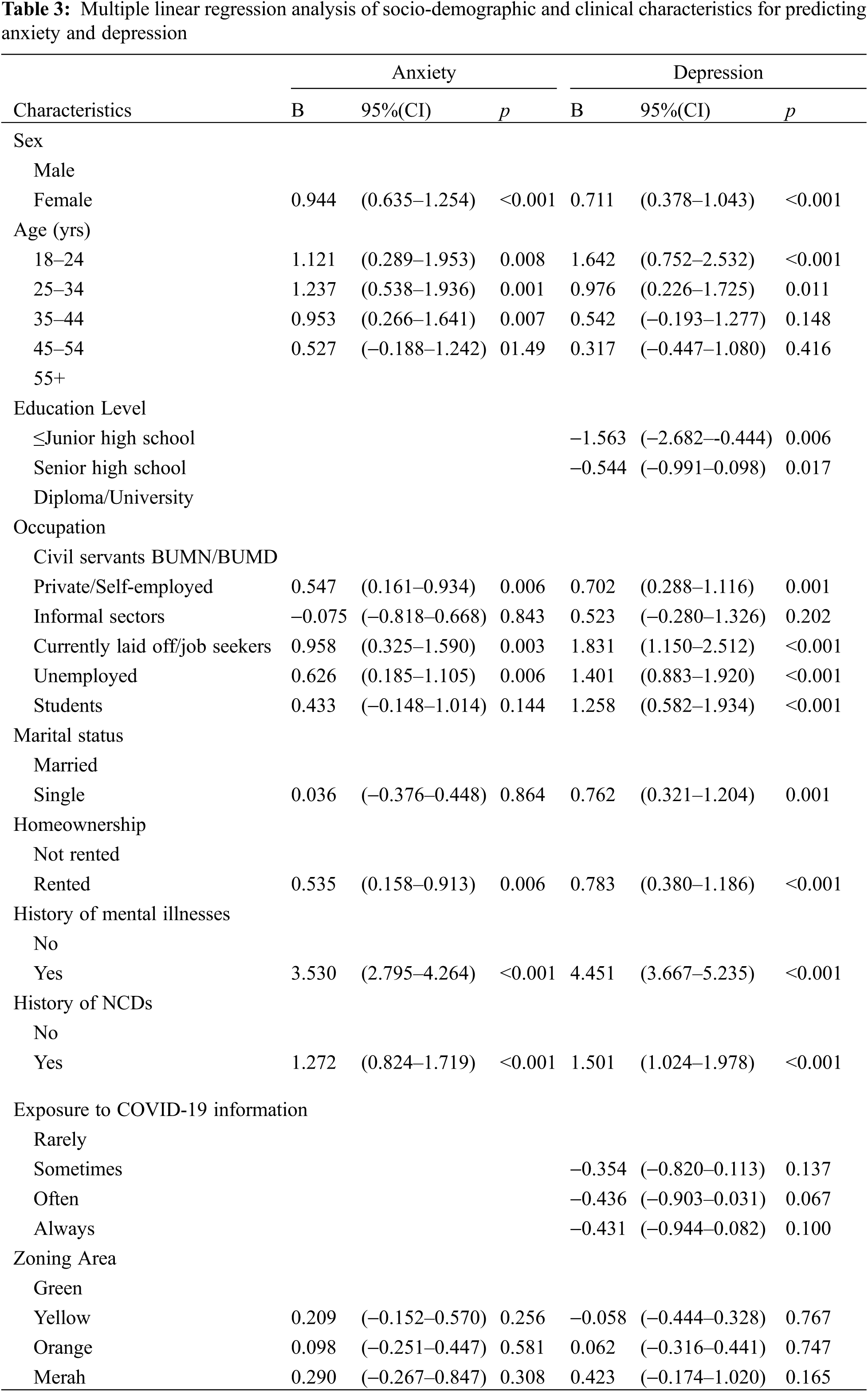

3.3 Multiple Linear Regression Analysis of Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics for Predicting Anxiety and Depression

Based on the results of multiple linear regression analysis (Table 3), the risk factors for anxiety are having a history of mental illnesses (B: 3.530; p < 0.001), having chronic diseases (B: 1.272; p < 0.001), currently laid off/job seekers (B: 0.958, p = 0.003), unemployed (B: 0.626, p = 0.006), working in the private sector or self-employed (B: 0.547, p = 0.006), female (B: 0.944, p < 0.001), and living in a rented house (B: 0.535, p = 0.006). The risk factors for depression are having a history of mental illnesses (B: 4.451; p < 0.001), having chronic diseases (B: 1.501;p < 0.001), currently laid off/job seekers (B: 1.831, p =< 0.001), unemployed (B: 1.401, p < 0.001), students (B: 1.258, p < 0.001), working in the private sector or self-employed (B: 0.702, p = 0.001), aged 18–24 years (B: 1.642, p < 0.001), aged 25–34 years (B: 0.976, p = 0.011), single (B: 0.762, p = 0.001), lived in a rented house (B: 0.783, p < 0.001), female (B: 0.711, p < 0.001), attending lower education that can reduce the risk of depression (B: −1.563, p = 0.006), and attending high school education as their latest education (B = −0.544, p = 0.017).

This study provides an overview of the mental health condition of Indonesians at the beginning of the pandemic, precisely 1 (one) month after the large-scale social restriction policy was implemented in several provinces. We found that 6.92% of participants had moderate-severe anxiety symptoms, and 8.57% had moderate-severe depressive symptoms. This finding is almost similar to the overview of Japanese society, where the percentage of depression is higher than anxiety: 10.9% of the community had anxiety with an average GAD-7 score of 3.73 (SD = 4.61), while 17.3% had depression with an average PHQ-9 score of 5.25 (SD-5.62) [12]. This pattern is also similar to the conditions that occurred in Hong Kong during this COVID-19 pandemic using the same instrument and assessment: depression (19%) higher than anxiety (14%) [13], even though the numbers in our study are lower compared to those two studies.

Psychological problems history is closely related to anxiety and depression, which also happened in Cyprus and Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ioulia, 2020 dan Ozin, 2020). The high level of anxiety and depression in people with a history of mental illness may have been associated with the illness relapse. During the pandemic, people are advised not to leave their homes. People with psychiatric symptoms have difficulty accessing health services, such as attending their regular visits or accessing their medicines, because hospitals have limited face-to-face services to reduce the risk of getting exposed to the virus [14]. Indonesia has established online medical services, including psychiatric services.

Having a history of chronic illness is closely related to anxiety and depression. Chronic comorbidities (especially hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease) have been identified as significant risk factors for mortality from 2019-nCoV [15]. In addition, individuals with chronic diseases have an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 [16]. In addition, the results of a Danish study on people with diabetes reveal their concern about getting COVID-19 [17]. Studies in Brazil also show higher anxiety scores in respondents with heart disease and diabetes than healthy respondents [18]. From the reports of health facility providers, research conducted by 202 health professionals in 47 countries also mentions depression as one of the comorbidities experienced by patients with NCDs (diabetes, hypertension, and COPD). Another study also said that the mental state of some to most of the patients is deteriorating [19]. In line with all these findings, increased levels of anxiety and depression were also found in individuals with chronic illnesses.

Employment status is closely related to anxiety and depression. Economic factors are significantly affected during the pandemic, especially after the restrictions on various community activities, including economic activities. The financial status of many people to support their survival has been disrupted; they had lower or even no income due to termination of work by companies that can no longer operate. The results of our study show that anxiety and depression are closely related to employment status, where the unemployed are susceptible to anxiety and depression. Our findings are similar to Japan’s [10] and China’s [18] conditions. A study conducted on 5,974 respondents in Mexico also showed that during the pandemic period, the mean scores for depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) were higher in students and those who were unemployed [20]. In addition, for job seekers, their chances of getting a job are now significantly reduced due to the decreasing vacancies [12]; this makes job seekers also experience anxiety and depression, as our study finds.

In this study, young age is associated with anxiety and depression. Some authors suggest more significant anxiety among more youthful age groups because they are more likely to get exposed to information circulated on social media, which may trigger stress [21–23]. This younger age group includes respondents still in school who were affected by mental health problems during the pandemic. Such issues may happen during the pandemic when parents are doing remote work from home, while at the same time, their children also have online learning from home. This fact was demonstrated in China, which showed an association between poorer mental health in those aged 12–21 years with educational difficulties arising from the restriction from attending the school and the uncertain examination period [24]. Another study also explains that older adults are more psychologically resilient than their younger counterparts which may be necessary when dealing with sources of stress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic [12].

The economic instability during the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted many community groups, including those who lived in rented houses/rooms. They usually have lower incomes and savings compared to the landlords. Although not all tenants have low income (poor), most of the poor are in the tenant group. This group is also vulnerable to losing their jobs or revenue during the pandemic, so they must fight even more challenging to fulfill their financial needs [25]. The difficulties experienced by tenants during the COVID-19 pandemic have been studied in the US. The most important manifestation is the inability to pay rent. About 16% of tenants could not pay their monthly rent in time. As for the tenants who could pay in time, they had to use their savings, owed some money, or ask for the help of friends and family. Threats of getting removed from their current rented house/room will always follow the tenants if they cannot pay, as 15% of tenants have experienced such a threat. This condition can trigger depression and anxiety [25].

Single participants are closely related to depression. This is in accordance with a study conducted in Canada on the population aged 18 years and over. They found that single/not married respondents have a higher risk of getting depression than respondents who got married [26]. A meta-analysis study also showed that single people had a worse prognosis for depression than married people [27]. This is because support from a partner is the most consistent social support that protects against depression in adults aged 18 years and over [28].

Women are closely related to anxiety and depression. This study adds to the evidence that women are more prone to experiencing anxiety and depression, as known in psychiatry [29]. Many previous studies are in line with these findings, such as in Cyprus from 3 to 9 April 2020 [29] and in April 2020 in Austria [30]. Women have been identified as the strongest predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms after the pandemic [31]. In a study from China, although during the pandemic, women were more aware of the COVID-19 disease than men and more adhered to the advice of health protocols, such as wearing masks and avoiding public spaces, women also felt that they were uncertain whether the pandemic could be controlled or not [32].

Education level is closely related to depression. Higher education had a greater risk for more significant anxiety and depression in this study. A study in Vietnam at the time of the implementation of the partial lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that the postgraduate education level had a higher stress level than the lower education level. This could be due to the high expectations of jobs in the future and financial pressures [33]. Higher education related to mental health problems occurred in China in early February 2020 and Iran in early March 2020 [7,34]. This may occur because of highly educated individuals’ high self-awareness of health conditions [35]. This fact is different from the result of another study which showed that people with lower education levels were associated with depression [36]. Although education can make one’s psychological well-being better because they may be able to encounter various economic pressures and difficulties, a higher education level can also be a risk factor for depression depending on multiple things such as gender, income level, occupation, marital status, and others [37].

Our research has a number of limitations. First, compared to face-to-face interviews, self-administered questionnaires have the potential for biased responses. Second, because this is an online poll, it is not representative, as it is confined to individuals with limited internet access. Thirdly, because the study is cross-sectional, it identifies only estimations and correlations of anxiety and depression with various factors, not their potential effects over time. This study does not investigate a number of crucial characteristics believed to influence anxiety and depressive disorders, such as stressful life events and patterns of social support. A prospective study with a larger sample size could provide light on the causes of anxiety and depression, regardless of the fact that performing such a study during the COVID-19 pandemic can be challenging.

In summary, our findings show that one third Indonesian had anxiety and depression during the period of activity restriction at the beginning of the pandemic. Anxiety and depression are strongly associated with a history of illnesses (psychological and chronic illnesses). In addition, they are also strongly related to community economic activities, where groups experiencing unfortunate financial events (affected by layoffs/job seekers, not working) are at risk of anxiety and depression. The young age group and students are also vulnerable to experiencing anxiety and depression. The importance of monitoring and continuity of treatment services for individuals with a history of psychological and chronic illnesses. Even though the government has implemented a social assistance program for these affected groups, other material or financial assistance can still be helpful for those experiencing financial difficulties.

Acknowledgement: We thank the head of the Center for Research and Development of Health Resources and Services, National Institute of Health Research and Development, Ministry of Health, Republic Indonesia, for allowing the online study. The authors would like to express our gratitude to Prof. Dr. Ekowati Rahajeng, who directs the study.

Author Contributions: RM and IYS were the main contributors. RM: conducted for the concept, analysis design, data analysis, and writing the original draft. IYS: conducted for the concept, writing original draft and manuscript compilation. SI, LI, TW, SI, NS, EN, and FPS were in charge of writing the background, discussing, and reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Perrin, P. C., McCabe, O. L., Everly, G. S., Links, J. M. (2009). Preparing for an influenza pandemic: Mental health considerations. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine, 24(3), 223–230. DOI 10.1017/S1049023X00006853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., Watson, P. J. (2002). 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part II. summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry, 65(3), 240–260. DOI 10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Coronavirus disease, W. H. O. (2019). (COVID-19) situation report–42 data as reported by 10 AM CET 02 march 2020 H. World Heal Organ [Internet].2020, 14(6), e01218. [Google Scholar]

4. Gugus Tugas Percepatan Penanganan COVID-19. Data Sebaran COVID-19 (2020). https://www.covid19.go.id/situasi-virus-corona/. [Google Scholar]

5. Shigemura, J., Ursano, R. J., Morganstein, J. C., Kurosawa, M., Benedek, D. M. (2020). Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 74(4), 281–282. DOI 10.1111/pcn.12988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Huang, Y., Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, 2–3. DOI 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, A. (2020). Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102076. DOI 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. DOI 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Nazari, N., Safitri, S., Usak, M., Arabmarkadeh, A., Griffiths, M. D. (2021). Psychometric validation of the Indonesian version of the fear of COVID-19 scale: Personality traits predict the fear of COVID-19. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–17. DOI 10.1007/s11469-021-00593-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Idaiani, S., Herawati, M. H., Mubasyiroh, R., Indrawati, L., Yunita, I. et al. (2021). Reliability of the general anxiety disorder-7 questionnaire for non-healthcare workers. 8th International Conference on Public Health, pp. 298–305. Surakarta, Indonesia. http://theicph.com/id_ID/2022/02/07/reliability-of-the-general-anxiety-disorder-7-questionnaire-for-non-healthcare-workers/. [Google Scholar]

11. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williamsm, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. DOI 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ueda, M., Stickley, A., Sueki, H., Matsubayashi, T. (2020). Mental health status of the general population in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 74(9), 505–506. DOI 10.1111/pcn.13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Choi, E. P. H., Hui, B. P. H., Wan, E. Y. F. (2020). Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10). DOI 10.3390/ijerph17103740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Özdin, S., Özdin, B., Ş. (2020). Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in turkish society: The importance of gender. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(5), 504–511. DOI 10.1177/0020764020927051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhou, F., Yu, T., Du, R., Fan, G., Liu, Y. et al. (2020). Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet, 395, 1054–1062. DOI 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang, B., Li, R., Lu, Z., Huang, Y. (2020). Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19. Aging, 12(7), 6049–57. [Google Scholar]

17. Joensen, L. E., Madsen, K. P., Holm, L., Nielsen, K. A., Rod, M. H. et al. (2020). Diabetes and COVID-19: Psychosocial consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in people with diabetes in Denmark—What characterizes people with high levels of COVID-19-related worries? Diabetic Medicine, 37(7), 1146–1154. DOI 10.1111/dme.14319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Teixeira, L., Freitas, R. L., Abad, A., Silva, J. A., Antonelli-Ponti, M. et al. (2020). Anxiety-related psychological impacts in the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. DOI 10.1590/SciELOPreprints.1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chudasama, Y. V., Gillies, C. L., Zaccardi, F., Coles, B., Davies, M. J. et al. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: A global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14, 965–967. DOI 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Fernandez, T., Betancourt-Ocampo, R. P., Reyes-Zamorano, G. (2020). A cross-sectional survey of psychological distress in a Mexican sample during the second phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. OSF Preprints, 1–23. DOI 10.31219/osf.io/wzqkh. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ahmed, Z., Ahmed, O., Aibao, Z., Hanbin, S., Siyu, L. (2020). Since January 2020 elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on elsevier connect, the company’s public news and information. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102092. DOI 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y. et al. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One, 15(4), 1–10. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mazza, C., Ricci, E., Biondi, S., Colasanti, M., Ferracuti, S. et al. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3165), 1–14. DOI 10.3390/ijerph17093165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L. et al. (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun, 87, 40–48. DOI 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Manville, M., Monkkonen, P., Lens, M., Green, R. (2020). COVID-19 and renter distress: Evidence from Los Angeles. Los Angeles; https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7sv4n7pr. [Google Scholar]

26. Bulloch, A., Williams, J., Lavorato, D., Patten, S. (2017). The depression and marital status relationship is modified by both age and gender. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 65–68. DOI 10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Buckman, J., Saunders, R., Stott, J., Arundell, L., O’Driscoll, C. et al. (2021). Role of age, gender and marital status in prognosis for adults with depression: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, e42. DOI 10.1017/S2045796021000342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gariépy, G., Honkaniemi, H., Quesnel-Vallée, A. (2016). Social support and protection from depression: Systematic review of current findings in western countries. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(4), 284–293. DOI 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.169094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Riecher-Rössler, A. (2017). Sex and gender differences in mental disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(1), 8–9. DOI 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30348-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Pieh, C., Budimir, S., Probst, T. (2020). The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 136, 1–19. DOI 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu, Y., Gayle, A., Wilder-Smith, A., Rocklöv, J. (2020). The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(2), 1–4. DOI 10.1093/jtm/taaa021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhong, B., Luo, W., Li, H., Zhang, Q., Liu, X. et al. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: A quick online cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 16(10), 1745–1752. DOI 10.7150/ijbs.45221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Le, H., Lai, A., Sun, J., Hoang, M., Vu, L. et al. (2020). Anxiety and depression among people under the nationwide partial lockdown in Vietnam. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 1–8. DOI 10.3389/fpubh.2020.589359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang, Y., Di, Y., Ye, J., Wei, W. (2021). Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychology Health & Medicine, 26(1), 13–22. DOI 10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B. et al. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry, 33(2), 1–4. DOI 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Markkula, N., Zitko, P., Peña, S., Margozzini, P., Retamal, C. (2017). Prevalence, trends, correlates and treatment of depression in Chile in 2003 to 2010. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(4), 399–409. DOI 10.1007/s00127-017-1346-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Assari, S. (2017). Social determinants of depression: The intersections of race, gender, and socioeconomic status. Brain Sciences, 7(12), 1–12. DOI 10.3390/brainsci7120156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |