| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.020108

ARTICLE

Pathways to Psychiatry Care among Children with Mental Health Problems

Neuropsychiatry Department, Ain Shams University, Cairo, 11566, Egypt

*Corresponding Author: Safi M. Nagib. Email: safi_nagib@yahoo.com

Received: 04 November 2021; Accepted: 21 February 2022

Abstract: Many children with mental health problems in Egypt, as in many other countries, do not receive the help they need. Investigating the pathways of care is crucial for the early detection and treatment of these children. This study examined referral patterns and the duration of untreated psychiatric illness of 350 children attending two urban clinical settings in Egypt. Diagnoses were made using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia for School-aged children present and lifetime (K-SADS-PL), Child behavior checklist (CBCL,) and the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale. For 46.3%, the most distressing symptom was behavioral problems. A delay in seeking psychiatric help was found. positive family history, and lower socioeconomic class were associated with delays in psychiatric consultation. For 39.7% of patients, the first contact was with a psychiatrist. Most children were referred by relatives. Awareness programs are needed to increase knowledge about and to decrease the duration of untreated illness.

Keywords: Pathways to care; children; service; mental illness; referral

Nomenclature

| ADHD | Attention Deficit hyperactive disorder |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| DUI | Duration of untreated illness |

| IQ | Intelligence quotient |

| K-SADS-PL | Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia for school-aged children present and lifetime |

| NE | Nocturnal enuresis |

| PCPs | Primary care physicians |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Psychiatric disorders among children are a common distressing problem. These disorders can be emotional, behavioral, or developmental and arise in the first two decades of life [1]. Around 10%–20% of children and adolescents experience mental illness worldwide and half of all psychiatric conditions start before the age of 14 [2].

WHO Mental Health Atlas (2005) reported a lack of adequate child and adolescent mental health services worldwide, especially in developing countries, including Egypt [3]. Families in developing countries may not spot psychiatric symptoms in their children except florid and explicit symptoms. Children mostly cannot express psychological distress and can only get professional help through somatic complaints. Many factors hinder psychiatric professional service access including stigma, cultural backgrounds, financial considerations, and service availability [4].

Consequences of untreated mental disorders in this age group include lifelong disability, substance abuse, and suicide [5]. Such delay in diagnosis and treatment can be determined by the pathways which the child and his caregivers took till finally seeking psychiatric services.

Lately, children and adolescents’ mental health services inadequacies have been spotted for attempts to develop, implement, and expand a revised paradigm of care [6,7].

In 2017, Egypt’s population reached around 95 million inhabitants with approximately 34.2% of them being children under the age of 15 [8]. An assessment that was conducted in Egypt in 2006 to evaluate the health care system has found that mental health occupied only 5% of undergraduate training for medical doctors while it occupied 10% of that for nurses. In a primary care setting, only less than 20% of patients undergo proper assessment and management of psychiatric conditions and referral pathways are quite inept with around only 1% of patients properly referred to a mental health professional. Although almost all schools employ health professionals, only about 1% of those are trained in mental health [9].

Health care providers and many of the population in Egypt are not as aware of children’s mental health problems as they should be. Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable as they do not participate in the decision-making process but can only seek care through the pathways that the parents may choose [10].

By identifying these pathways, improvements in offering psychiatric help and raising awareness of mental illness can be reached which can greatly benefit both children and surrounding individuals and consequently benefiting the entire society.

In the recent years improvements in the mental health sector in Egypt, had resulted in the separation between the services provided for children and those for adolescents. In the current study we were more interested in investigating the pathways of care for children who are more vulnerable. In light of the aforementioned, we aimed to identify the pathways to services and the time taken to reach formal psychiatric care. We hypothesized that there is a delay in the referral pathways to psychiatric care.

The study sample consisted of 350 children (new or old), aged 2–12, which is the age range that presents to the child psychiatry outpatient clinics in the study settings. Cases were recruited over 15 months period (from January 2020 to March 2021) from two tertiary care settings, the first is the child psychiatry outpatient clinic of the Okasha Institute of Psychiatry, which belongs to Ain Shams University Hospitals (Group I) (n = 181), and the second is the child outpatient clinic of Al Abbasia governmental mental hospital which is operated by the Health Ministry’s General Secretariat of Mental Health and Addiction Treatment (Group 2) (n = 169). Both clinical settings serve as a catchment area of more than the third of greater Cairo including areas around greater Cairo as well. Choosing to conduct the study at the two hospitals was aiming to better generalization of the results, we also hypothesized that there would be a difference between the two hospitals regarding the duration of untreated illness and characteristics of participants, may be due to the higher stigma associated with seeking help at Al Abbasia Hospital as the oldest and most famous psychiatric hospital in Egypt specialized only in mental health [11] in comparison to Ain Shams University Hospitals which are 13 hospitals of different specialties located in one campus. Cases that refused to participate or withdrew during the interview were excluded.

The sample size was calculated using Stata 10 program. after reviewing the existing literature of similar studies [10], setting α error at 5% and achieving power of 80%, the needed sample is at least 350 subjects.

Due to the current COVID 19 pandemic, clinics in both places stopped working and recruitment was held for 3–4 months and resumed with decreased numbers of children being examined, that is why the current study was extended until the needed number of cases was recruited.

Subjects were recruited over 15 months period (from January 2020 to March 2021). Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ain Shams University Faculty of Medicine Ethical Committee and the Ethical Committee of Al Abbasia Psychiatric Hospital. An informed written consent was obtained from the guardians of children participating in the study after being informed about the nature and objectives of the study. Confidentiality of the participants was ensured.

The study was conducted at the outpatient clinics of the two hospitals, Both the children and their caregivers were interviewed. A full psychiatric history and examination according to DSM IV were performed using the K-SADS-PL [12]. Sociodemographic data were recorded from one of the parents using the updated and re-validated version of Fahmy’s socioeconomic scale [13,14]. Psychiatric contact data were collected using an interviewer-designed checklist which included information about the family’s first contact for consultation, the source of the referral, the duration of untreated illness, the most distressing symptom, and traditional healers’ help history. The severity of internalizing and externalizing behaviors of children was assessed using the Arabic version of the child behavior checklist, completed by the caregiver [15,16]. The interview took around 60 min to complete. Children were then referred for assessment of their intellectual functions using the Arabic version of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale fifth edition [17] performed by a well-trained psychologist from the staff working at Okasha institute of psychiatry to diagnose intellectual disability in children.

Statistical analysis

The collected data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science, version 25 (SPSS 25) [18]. Descriptive statistics included mean, standard deviation (±SD) for parametric data, and Median, Interquartile range (IQR), frequency, and percentage for non-parametric data. Analytical statistics included: (1) Chi-Square test was used to compare between groups with qualitative data. (2) Independent t-test was used to compare between two groups with quantitative data and parametric distribution. (3) Mann Whitney test (U test) was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference of a non-parametric variable between two study groups. (4) The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference between more than two study group ordinal variables. Correlation analysis using Spearman method was used. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

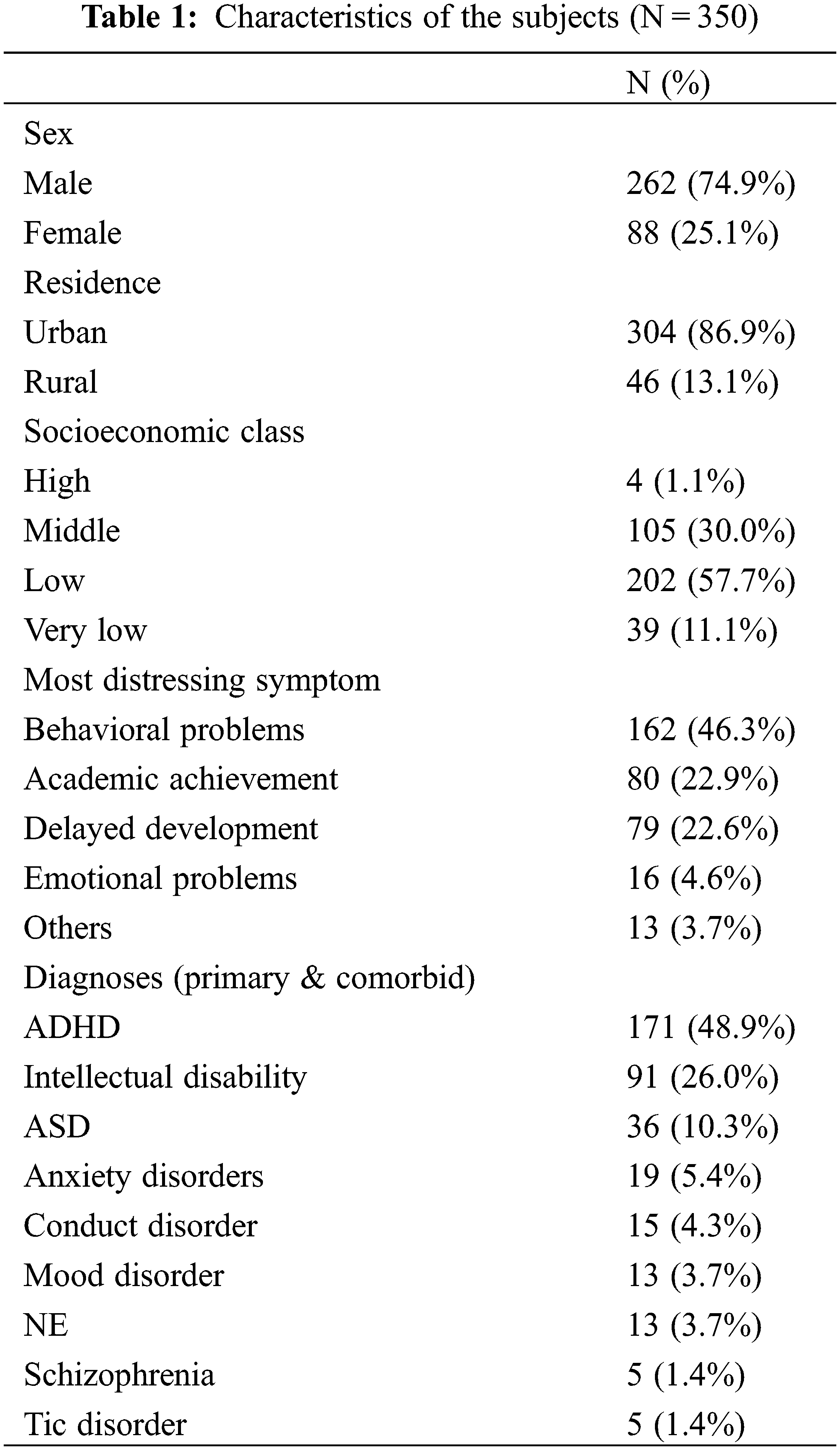

3.1 Characteristics of Subjects

Of the 350 subjects who participated in the study, 181 were recruited from Okasha Institute of Psychiatry, Ain Shams University (Group I) while 169 were recruited from Al Abbasia Governmental mental Hospital (Group 2). The study group averaged 7.92 (SD = 2.40) years of age.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 350 participants. The most common diagnosis was attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); followed by intellectual disability while the most common distressing symptom reported by the cases was behavioral problems, followed by poor scholastic performance (Table 1). The mean duration of illness before psychiatric consultation was 27.33 (SD = 19.63) months.

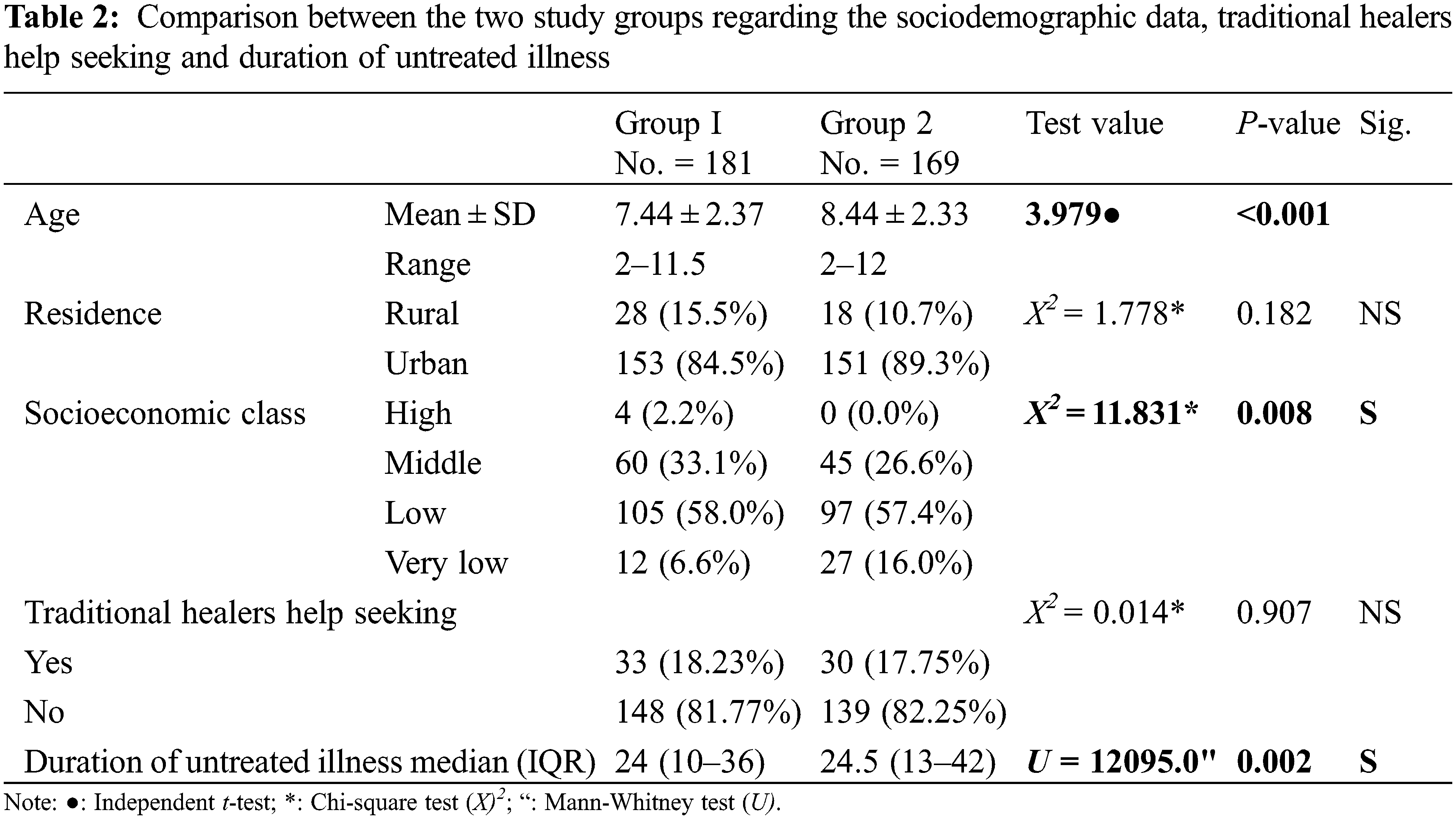

On comparing the sociodemographic data of the two groups, we found that the mean age of group 2 was significantly higher than that of the children in group I. There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups as regards socioeconomic class. Group I had a significantly shorter duration of untreated illness compared to group 2 (Table 2).

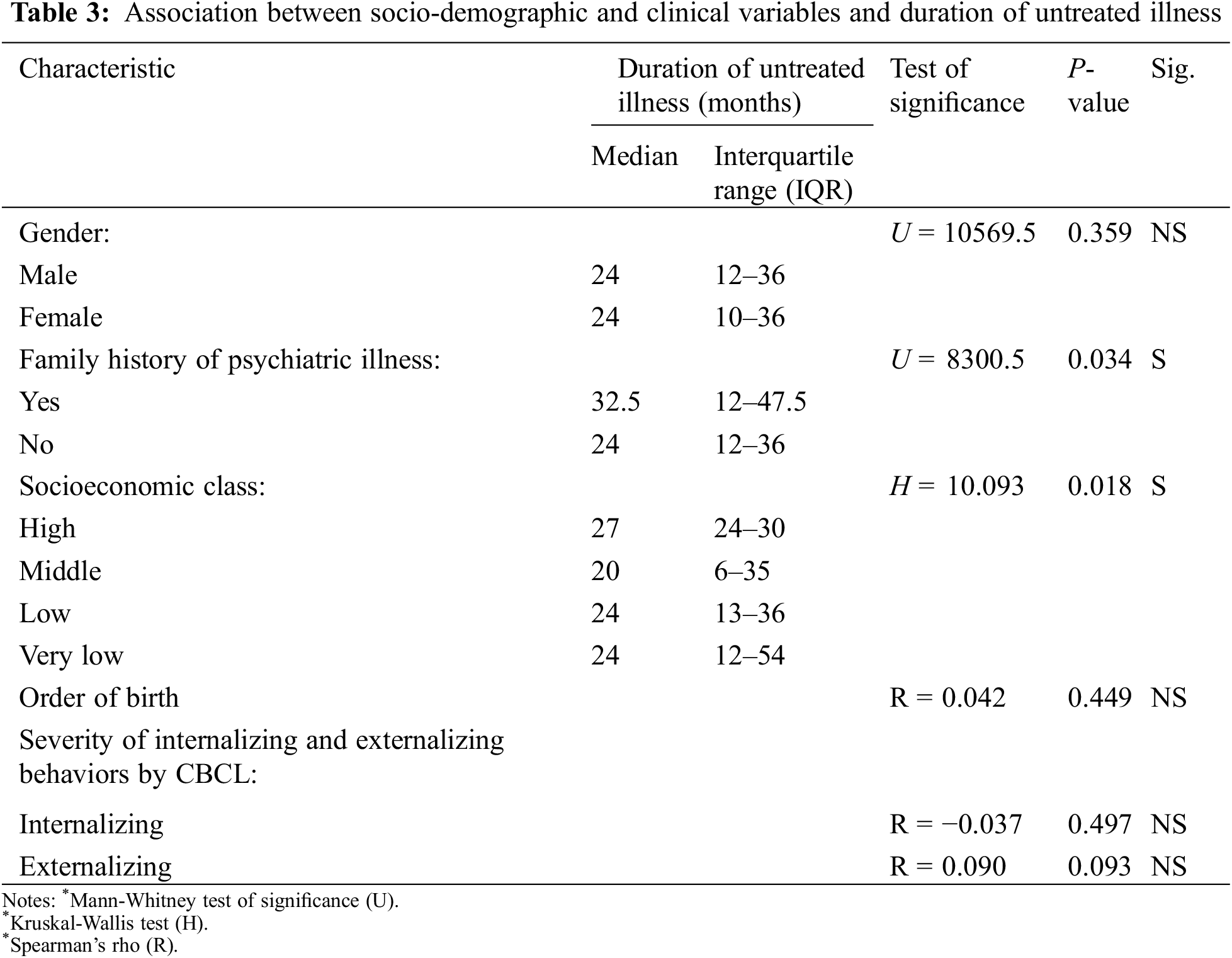

As shown in Table 3, it was found that lower socioeconomic class, and positive psychiatric family history were significantly associated with delayed treatment-seeking. Parents in a middle social class sought consultation earlier than those in a low or very low social class. Whereas the order of birth, gender, and severity of externalizing and internalizing behaviors were not associated with the duration of untreated illness.

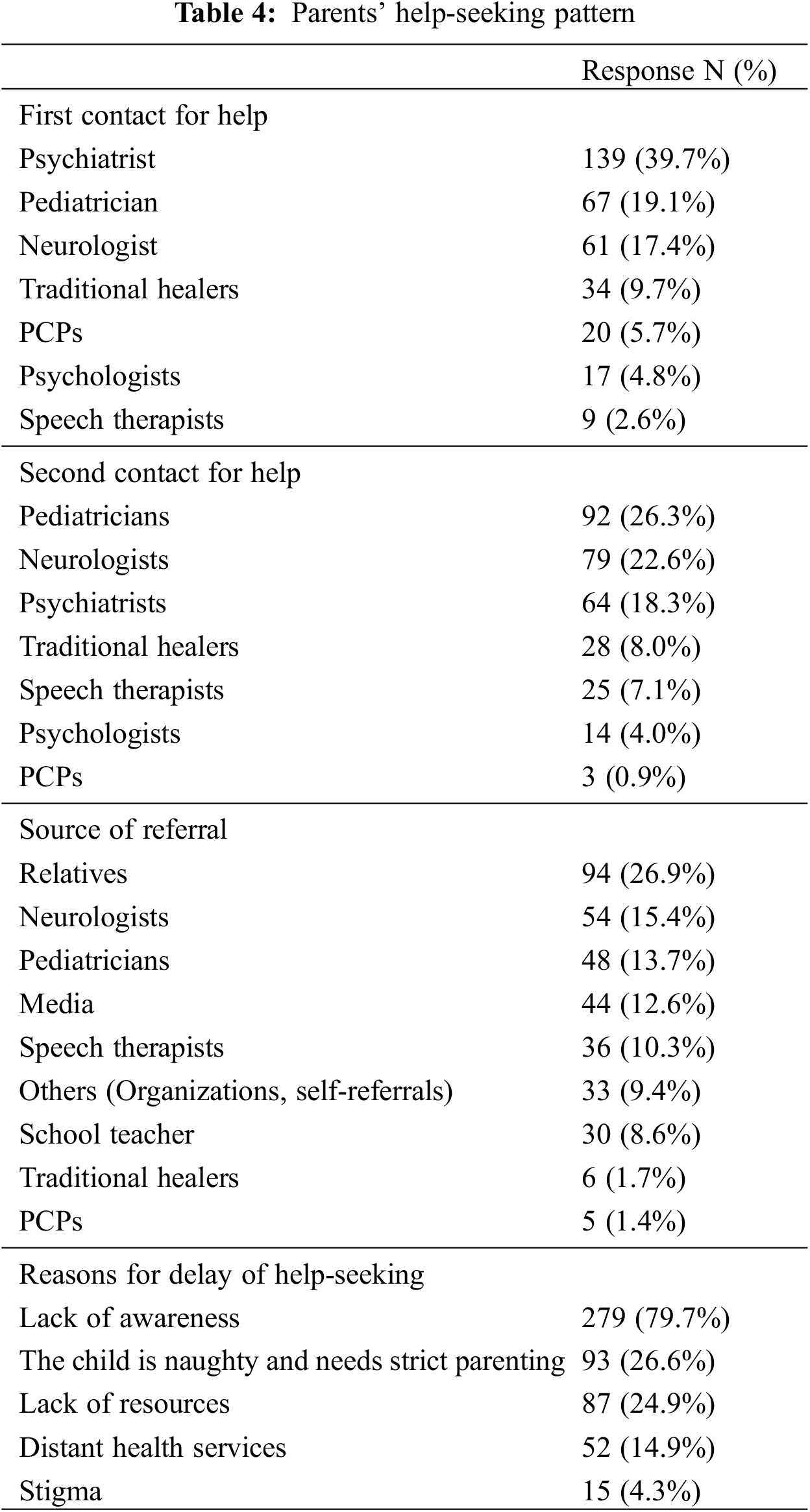

3.2 Parents’ Help-Seeking Pattern

Most parents first contacted a psychiatrist (39.7%) about their child’s mental health condition; pediatricians were the first contact in 19.1% of cases. Other specialties first contacted included neurology and PCPs. Traditional healers were the first contact in 9.7% of cases. Many participants had sought second opinion about their children’s condition, where 26.3% cases had consulted pediatricians, others consulted for a second advice from neurologists, other psychiatrists, and traditional healers. As regards the referral source, the largest proportion of patients were referred by relatives. Lack of awareness was the most commonly reported reason for the delay in seeking psychiatric help by families (Table 4).

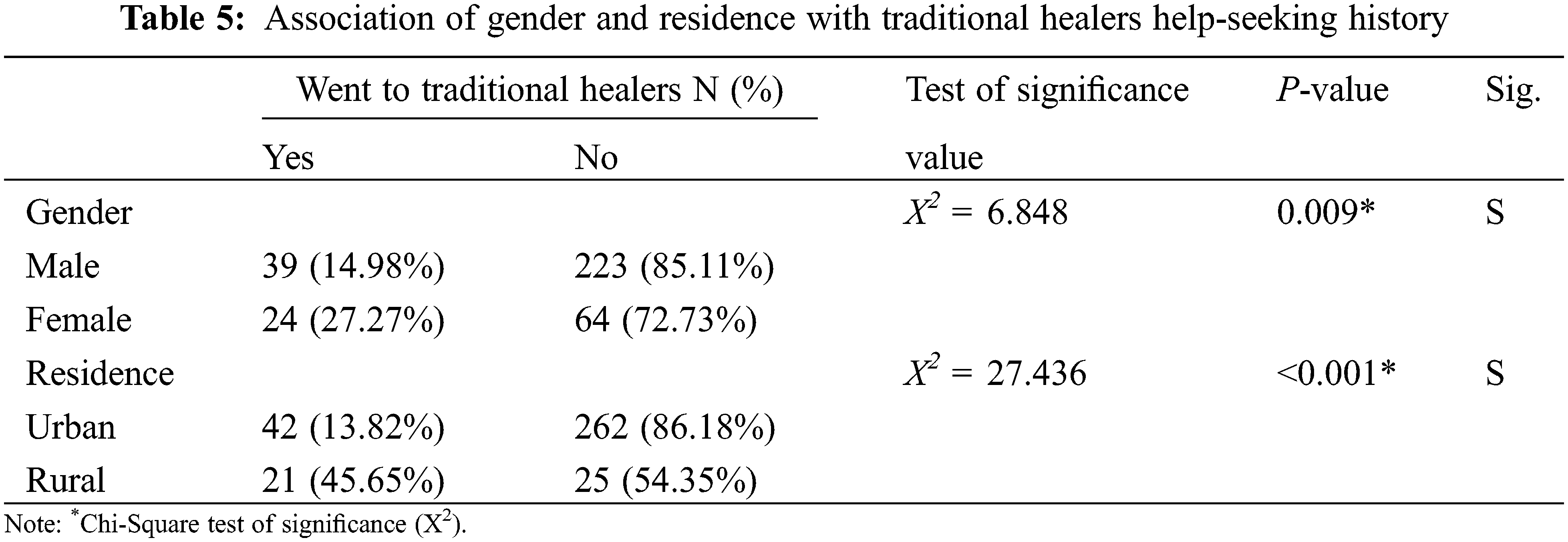

Eighteen percent of the sample sought help at traditional healers. Easy accessibility was the most common reason reported for seeking help at traditional healers (79.4%), while recommendations from relatives were stated by 60.3% of the parents, and 33.3% stated that it was also because of their low expenses. Table 5 shows that a higher percentage of females (27.27%) sought help at traditional healers compared to males (14.89%). Also, a higher percentage of those living in rural areas (45.65%) sought traditional healers’ help compared to those living in urban areas (13.82%).

The majority of the sample in the current study consisted of males (74.9%) which may show that parents are more concerned with behavioral problems in males. This appears to be in concordance with previous studies which stated that girls were less likely to be recognized by families as having a disorder [19].

On comparing the sociodemographic data of the two groups, we found that the mean age of group 2 (8.44) was significantly higher than that of group I (7.44), which might indicate that families knew better about psychiatric services available at the university hospital, and the more stigma associated with seeking help at El Abbasiya governmental hospital, the most famous psychiatric hospital in Egypt. Also, we found that there was a significant difference between the two groups as regards the socioeconomic status with the cases belonging to lower socioeconomic class going to Al Abbasia governmental hospital which may be due to the availability of more affordable services.

In this study, the most common diagnosis was externalizing disorder (ADHD and conduct disorder) with 53.2% patients, which was similar to another study conducted in India which found that children with hyperkinetic disorder and conduct disorder represented the majority (37.5%) of the sample [20]. Meanwhile, 10.2% of the sample met the criteria for childhood anxiety, mood disorder, or schizophrenia which was close to the findings of Hussein et al. [10]. Still, this was not in line with a study conducted in Norway which found that cases with these diagnoses represented 42% [21]. It may be because externalizing behaviors are more distressing to families in Egypt than internalizing behaviors. Around 26.0% of our sample had intellectual disability while 10.3% had autism disorder, this was also close to what Hussein et al. found in their study [10]. It took families an average of 27.33 ± 19.63 months to reach psychiatric service. This may indicate that parents tolerated the child’s condition and tried to control his behavior at home or by seeking help through other fields before seeking psychiatric help. This finding is close to previous studies that reported that patients with ADHD took an average of 2.6 years to reach mental health services [22], but it was longer than 1.5 years found in the study that was conducted in Iran by Ghanizadeh [23]. The discrepancy can be owed to different clinical settings between the two studies and different sample size and diagnoses, as his study included 119 children with ADHD.

When comparing between the two groups regarding the duration of untreated illness, cases in group I were found to have reached psychiatric services earlier than cases in the second group. This may be due to the availability of other specialties in university hospitals that serve cases coming from all over the country with earlier identification and referral to psychiatric services and perhaps due to the more stigma associated with seeking help at Al Abbasia governmental hospital.

Regarding the most distressing symptom, Behavioral problems were the most frequently reported symptom. This finding is consistent with other studies that found that behavioral issues were the commonest reason that motivated the families to seek help [10,22]. This may confirm the suggestion that regardless of the nature of a child’s mental disorder, it is the child’s disturbing behavior that motivates the family to seek treatment.

Meanwhile, 22.9% stated that scholastic impairment and underachievement was the most distressing symptom for them. In Egypt, parents give great value to school grades, so if the child’s grades are falling behind and teachers are not satisfied, parents get motivated for help-seeking. This agreed with another study that stated that educational difficulties were an important encouraging factor for help-seeking by parents [24]. This was also close to the findings by Hussein et al. [10] who found that around 18% of the families reported scholastic impairment as the most distressing symptom.

In this study, it was found that faster utilization of psychiatric services was associated with better socioeconomic status. These findings were in line with the study by Hussein et al. [10] that found that willingness to use psychiatric services was associated with higher socioeconomic status which suggests the role played by financial resources in determining the pathway of care.

Also, we found that family history of psychiatric illness was associated with longer DUI. Several factors may affect DUI including stigma; denial; experience with psychiatric service and/or treatments. They were afraid that they will stigmatize their child and that he will be labelled as having a mental disorder. Similarly, Oliva et al. found that patients with ADHD and positive family history for ADHD had a longer DUI [25]. On the other hand, that was different from what was suggested in another study which found that having a family history of psychiatric illness was an important point in the early identification of mental illness by pediatricians [26]. This difference may be because the other study was based on the identification of the cases by the pediatricians and not by other pathways including the family themselves.

We found that the severity of internalizing or externalizing behaviors of children measured by CBCL did not show any significant correlation with DUI. This was the same as in another study where it was found that the severity of ADHD, measured on the validated scale, did not show any significant correlation with DUI [25], supporting findings by other studies [22,23].

In this study, most families, 39.7%, firstly contacted a psychiatrist regarding their child’s condition. This finding is in line with another study in which the majority of ADHD patients sought primary advice from psychiatrists [27]. Which may be a promising finding indicating better awareness about mental disorders with earlier referral to psychiatric care.

Furthermore, 19.1% contacted pediatricians at first, while other specialties first contacted included: neurologists, PCPs, psychologists, and speech therapists. This could be due to the confusion of the public regarding the nature of their children’s symptoms, this also uncovers the hidden, yet important role that other healthcare and mental health professions play as regards to providing proper guidance to psychiatric services, it could also be due to the stigma associated with visiting a psychiatrist, which pushes parents to consult other professions first.

In this study, 9.7% of the families first sought help for their children’s symptoms at traditional healers, in Egypt, traditional religious healers have a powerful influence in the pathway of care for patients with mental health problems [28].

We found that the majority of the cases were referred to the psychiatric service by relatives 26.9%. This can be a result of parent’s doubts about their child’s behavior, so they would seek advice from relatives in search of help or looking for a similar experience. This finding came in agreement with the study by Abdulmalik et al. [29] who found that the commonest source of referral and information about mental health services was via community networks and neighbors. Meanwhile it was found that neurologists referred 15.4% of the cases. This can be due to the confusion regarding the nature of mental health problems and mixing up between the two specialties.

Pediatricians, on the other hand referred 13.7% of the cases. It was reported that referral from a pediatrician to psychiatric care is affected by several factors: including parental anxiety, concern about child’s behavior and/or symptoms, and positive family history of psychiatric illness [26].

Media referred 12.6% of cases, it was reported in the study by Ghanizadeh [23], that radio and television were the main sources of knowledge about ADHD as a psychiatric disorder needing help from the public. Abdulmalik & Sale recognized media as an important source of information about available mental health services [29].

Only 8.6% of the cases were referred by schoolteachers, this came in agreement with another study that found fewer referrals by schoolteachers and reported insufficient teachers’ knowledge about cases of ADHD [22]. It was suggested that a compulsory child mental health training program among schoolteachers is mandatory to facilitate the identification of symptoms thus shortening the duration of illness before reaching children’s mental health services [30].

Meanwhile, only 3.1% of the cases were referred by traditional healers and PCPs, this refers to the inadequacy of referral to psychiatric services by traditional healers and by primary care physicians which is like the findings of Hussein et al. [10] who found that traditional healers referred 5% of cases while only 2% of the cases were referred by PCPs. This low percentage referred from primary care units may reflect the insufficient psychiatric training and recognition received by PCPs [31].

In this study, when parents were asked about the reason for the delay in seeking psychiatric help for the child’s symptoms, 79.7% stated that lack of awareness about their children’s symptoms was the reason behind their delay in help-seeking. This was like previous studies that found that the most frequently reported reason for the delay was poor public knowledge about mental health services and mental disorders [23,27].

Another common reason reported by 26.6% of the sample was the belief that the child is naughty, and his behavior needed strict rules to be controlled. This reason was mentioned by other studies that parents usually tend to attribute symptoms to behavioral or cognitive difficulties rather than a psychiatric condition [24,30]. Lack of resources was stated as the reason for the delay in seeking psychiatric help by 24.9% of parents. Meanwhile, 14.9% of the families reported that distant health services were the reason for such delay and that they had difficulty deciding to go such long distances to seek help.

In Arabic countries, social and religious beliefs have a powerful influence. Patients who go to sheikhs believe that their symptoms are due to evil spirits, or a jinni and those sheikhs may be able to cure them by controlling the jinn and forcing it to leave their bodies. In the current study traditional healers had been consulted by 18% of cases and the majority of these consultations were before psychiatric advice (55.5%). This came in agreement with what was found by other studies [10,32]. This also explains why most patients in our study seeking help at traditional healers were treated by religious rituals (85.7%), the same as found in the study by Hussein et al. [10].

Easy accessibility was the commonest reason stated for choosing to seek help at traditional healers this was the same as reported in the study by Hussein et al. [10]. This may explain why a higher percentage of those who lived in rural areas visited traditional healers where it is easier to reach these services.

We found that the percentage of females (27.27%) who sought help at traditional healers was significantly higher than the percentage of males (14.89%). This came in line with previous studies in which being a female was associated with higher rates of seeking non-psychiatric care [32], it may because of culture beliefs and mental illness stigma fear. Families of female patients would fear that their daughter’s future chances of getting married might be threatened if they were known to have a psychiatric illness.

We conclude that there was a delay in seeking psychiatric help and that externalizing behavioral problems were the main reason for seeking help, awareness programs are needed to increase the public knowledge about symptoms of internalizing problems and to decrease the duration of untreated illness.

A limitation of our study was that it did not explore the pandemic effect as a factor influencing the DUI and pathway of care, also, a recall bias was inevitable due to the retrospective nature of the study, families were self-reporting previous data which were not officially recorded.

Acknowledgement: We wish to thank the patients who participated in this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Akhter, J., Islam, M. A., Maruf, M. M., Gofur, T. B. (2020). Pattern of psychiatric morbidity in pediatric outpatient department. Bangladesh Journal of Psychiatry, 31(1), 1–6. DOI 10.3329/bjpsy.v31i1.45365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. World Health Organization (2020). Improving the mental and brain health of children and adolescents. https://www.who.int/activities/improving-the-mental-and-brain-health-of-children-and-adolescents. [Google Scholar]

3. World Health Organization (2005). Atlas: Child and adolescent mental health resources: Global concerns: Implications for the future. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43307. [Google Scholar]

4. Jesmin, A., Mullick, M. S. I., Rahman, K. M., Muntasir, M. M. (2016). Psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents attending pediatric out patient departments of tertiary hospitals. Oman Medical Journal, 31(4), 258–262. DOI 10.5001/omj.2016.51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang, P. S., Berglund, P., Olfson, M., Pincus, H. A., Wells, K. B. et al. (2005). Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 603–613. DOI 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lourie, I. S., Stroul, B. A., Friedman, R. M. (1998). Community-based systems of care: From advocacy to outcomes. In: Epstein, H., Kutash, K., Duchnowski, A. J. (Eds.) Outcomes for children and youth with behavioral and emotional disorders and their families: Programs and evaluation best practices, pp. 3–19. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. [Google Scholar]

7. Warren, J. S., Nelson, P. L., Mondragon, S. A., Baldwin, S. A., Burlingame, G. M. (2010). Youth psychotherapy change trajectories and outcomes in usual care: Community mental health versus managed care settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 144–155. DOI 10.1037/a0018544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (2017). Census–population (governorate). https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/Publications.aspx?page_id=7195&Year=23354. [Google Scholar]

9. World Health Organization Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS) (2006). Report on Mental Health System in Egypt. WHO and Ministry of Health, Cairo, Egypt. https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/who_aims_report_egypt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

10. Hussein, H., Shaker, N., El-Sheikh, M., Ramy, H. A. (2012). Pathways to child mental health services among patients in an urban clinical setting in Egypt. Psychiatric Services, 63(12), 1225–1230. DOI 10.1176/appi.ps.201200039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Okasha, A. (1993). Psychiatry in Egypt. Psychiatric Bulletin, 17(9), 548–551. DOI 10.1192/pb.17.9.548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., Ryan, N. (1996). Kiddie-sads-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, School of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

13. El-Gilany, A., El-Wehady, A., El-Wasify, M. (2012). Updating and validation of the socioeconomic status scale for health research in Egypt. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 18(9), 962–968. DOI 10.26719/2012.18.9.962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fahmy, S. (1983). Determining simple parameters for social classifications for health research. Bull High Inst Public Health, 13, 95–108. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1571980074220648960. [Google Scholar]

15. Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the teacher’s report form and 1991 profile. University Vermont/Department Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

16. Yunis, F., Zoubeidi, T., Eapen, V., Yousef, S. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Child Behavior Checklist/2-3 in an Arab population. Psychological Reports, 100(3), 771–776. DOI 10.2466/pr0.100.3.771-776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hanoura, M., Abdel, H. (2002). Stanford-binet intelligence test: Arabic version. Cairo: Anglo Press. [Google Scholar]

18. IBMCorp IBM, S. P. S. S. (2017). Statistics for Windows, version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

19. Wright, N., Moldavsky, M., Schneider, J., Chakrabarti, I., Coates, J. et al. (2015). Practitioner review: Pathways to care for ADHD–A systematic review of barriers and facilitators. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(6), 598–617. DOI 10.1111/jcpp.12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Joseph, R. G., Kallivayalil, R. A., Rajeev, A. (2020). Pathways to care in children-perspectives from a child guidance clinic in South India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 102310. DOI 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Reigstad, B., Jørgensen, K., Wichstrøm, L. (2004). Changes in referrals to child and adolescent psychiatric services in Norway 1992–2001. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(10), 818–827. DOI 10.1007/s00127-004-0822-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yamauchi, Y., Fujiwara, T., Okuyama, M. (2015). Factors influencing time lag between initial parental concern and first visit to child psychiatric services among ADHD children in Japan. Community Mental Health Journal, 51(7), 857–861. DOI 10.1007/s10597-014-9803-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ghanizadeh, A. (2007). Educating and counseling of parents of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Patient Education and Counseling, 68(1), 23–28. DOI 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wilcox, C. E., Washburn, R., Patel, V. (2007). Seeking help for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in developing countries: A study of parental explanatory models in Goa, India. Social Science & Medicine, 64(8), 1600–1610. DOI 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Oliva, F., Malandrone, F., Mirabella, S., Ferreri, P., di Girolamo, G. et al. (2021). Diagnostic delay in ADHD: Duration of untreated illness and its socio-demographic and clinical predictors in a sample of adult outpatients. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 15(4), 957–965. DOI 10.1111/eip.13041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Heneghan, A., Garner, A. S., Storfer-Isser, A., Kortepeter, K., Stein, R. E. et al. (2008). Pediatricians’ role in providing mental health care for children and adolescents: Do pediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists agree? Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 29(4), 262–269. DOI 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31817dbd97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Arya, A., Agarwal, V., Yadav, S., Gupta, P. K., Agarwal, M. (2015). A study of pathway of care in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 17, 10–15. DOI 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.07.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Assad, T., Okasha, T., Ramy, H., Goueli, T., El-Shinnawy, H. et al. (2015). Role of traditional healers in the pathway to care of patients with bipolar disorder in Egypt. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(6), 583–590. DOI 10.1177/0020764014565799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Abdulmalik, J. O., Sale, S. (2012). Pathways to psychiatric care for children and adolescents at a tertiary facility in Northern Nigeria. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 3(1), 15–17. DOI 10.4081/jphia.2012.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Anand, P., Sachdeva, A., Kumar, V. (2018). Pathway to care and clinical profile of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in New Delhi, India. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, 25(2), 114. DOI 10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_142_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Blacker, C., Clare, A. (1987). Depressive disorder in primary care. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 737–751. DOI 10.1192/bjp.150.6.737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kamal, A. M., Abd Elhameed, M. A., Siddik, M. T. (2013). A study on nonpsychiatric management of psychiatric patients in Minia Governorate, Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Psychiatry, 34(2), 128. DOI 10.7123/01.EJP.0000427172.96958.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |