| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.019167

ARTICLE

Support and Companionship in Virtual Communities: Establishing a COVID-19 Counseling Network for Soldiers and the Collective Healing Phenomenon

Fu Hsing Kang College, National Defense University, Taipei, 11258, Taiwan

*Corresponding Author: Pao-Lung Chiu. Email: paupau1980@hotmail.com

Received: 07 September 2021; Accepted: 24 February 2022

Abstract: Counseling people, particularly those in the military engaged in group living, who are in quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic is a challenge. Therefore, supporting the people in quarantine who are experiencing psychological and interpersonal problems has become a new challenge in military mental health. This study’s primary concern was how to overcome the problems caused by physical quarantine. The study subject was a virtual counseling network and its operating experience during the quarantine period in Taiwan amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic. For soldiers who mainly live in groups, this study discussed how the virtual counseling network combined with the existing military support group to determine what influence the network had on people in quarantine. This study found that this group exhibited four types of experiences: togetherness, empathy, confidence, and belonging and cohesion. Such experiences are beneficial for group healing through mutual support and companionship. Collective cohesion and psychological healing can be achieved through a virtual community. This is worthy of attention, particularly in the pandemic or post-pandemic era. Physical isolation has become a fact of life, and such isolation is not just isolation from disease but also between regional boundaries. Counseling and support systems in virtual space or the operation of virtual teams must be considered for the future.

Keywords: Counseling network; stigmatization; psychological counseling; virtual interpersonal interaction; recovery

Quarantine is a critical measure that has been taken during the COVID-19 pandemic, and its main function is to prevent viral infections from spreading [1]. However, this measure also influences people’s lifestyles at various levels. Such influences generate highly negative effects. Factors such as fear, social isolation, and shame influence personal mental health [2] and even collective mental health [3].

Notably, a case of COVID-19 cluster infection of the Dunmu Fleet was reported on April 16, 2020. After the first case of COVID-19 was detected in April 16, tests were immediately conducted on all members. To prevent the spread of the outbreak, suspected cases were individually quarantined for 14 days (beginning April 17). During the quarantine, the patients were forbidden to leave their quarantine rooms or have physical contact with anyone. The quarantine measure was abrupt, and the patients had no psychological preparation beforehand. The patients were worried not only about their health but also whether they had already infected others. Moreover, they were concerned about how they would be viewed after recovery. In addition, fear and misunderstanding about the disease could have grown because of their physical isolation. This fear and misunderstanding could be related to uncertainty about their environment and the disease as well as the conditions of their peers. Furthermore, diseases can lead to labelling and stigma, which influence interpersonal interactions [4,5]. To prevent such psychological problems in quarantined patients, researchers used telephone calls to attempt to understand the physical and mental conditions of the quarantined fleet members and then proposed a virtual counseling network. After consent from all the quarantined patients was obtained, a communication channel was established immediately to provide practical counseling. In addition, all the quarantined patients were allowed to participate in the counseling network through snowballing.

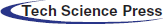

Hence, this study established a virtual counseling network as a treatment intervention focused on providing quarantined individuals with interpersonal interactions, support, and company from a collective perspective. Under the existing organizational cultural characteristics, the counseling team introduced the people in physical quarantine to the virtual support community. In addition, the virtual counseling network was constructed through self-help and mutual-help methods to address this temporary collective crisis. The quarantine period was mainly from April 17 to May 03. This study, starting with the virtual counseling network, explained the influence of support provided by the quarantined individuals themselves during the physical operation of the quarantine period in the military. The following questions were addressed: How did the network combine and operate with the existing support groups in the military? What influence did the network have on the quarantined individuals? In this paper, the operation process of the virtual counseling network is first introduced. Subsequently, the findings regarding the practice of the operation process are explained. Finally, suggestions are provided for workers in actual practice.

2 Intention and Operation Model of the Virtual Counseling Network

The virtual counseling network was mainly run through two web services: “Stay together with unabated love” and “Pandemic prevention with love.” The network was provided for military members to form support groups. The psychological distance caused by physical isolation was broken through expressing empathy, seeing others’ experiences and diaries, and providing psychoeducation. Thus, the purposes of self-help and mutual help were achieved (Fig. 1). The related intentions of the virtual counseling network are described as follows.

Figure 1: The virtual counseling network’s operation

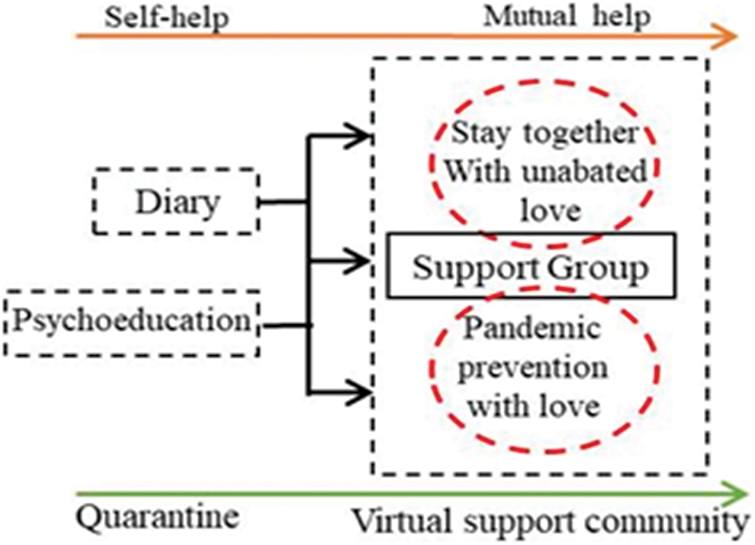

2.1 Stay Together with Unabated Love

(1) Purpose: This platform mainly provided a gathering place to provide support and offer a place for voices from various places, and this psychological support was provided to the quarantined individuals through the collective participation of participants. The public could provide videos or encouraging words to the counseling team. Then, the videos and encouraging words were published on the platform to be shared with the group members through data processing and the design of the web page.

(2) Function: “Stay together with unabated love” was a Facebook group founded in response to the aforementioned incident. The “Stay together with unabated love” activity was launched by the researchers on this social platform. Participants could show support and care for quarantined individuals directly on this platform (Fig. 2). In addition, the research team provided an Internet mailbox for the public and the military social group so they could show their care for this group.

(3) Operation model:

1. While advocating the importance of destigmatization, supportive power, and companionship, the research team mainly encouraged military personnel and the public to participate in this online activity by promoting the Facebook group on Internet platforms and news media (such as Youth Daily News).

2. People were asked to invite peers to write (or record) messages for the quarantined officers and military students. The collected messages were made into image files to show to the public. People’s love could be felt through such collective power. Moreover, the quarantined individuals were able to feel care and support from the outside world.

Figure 2: Activity platform of “Stay together with unabated love”

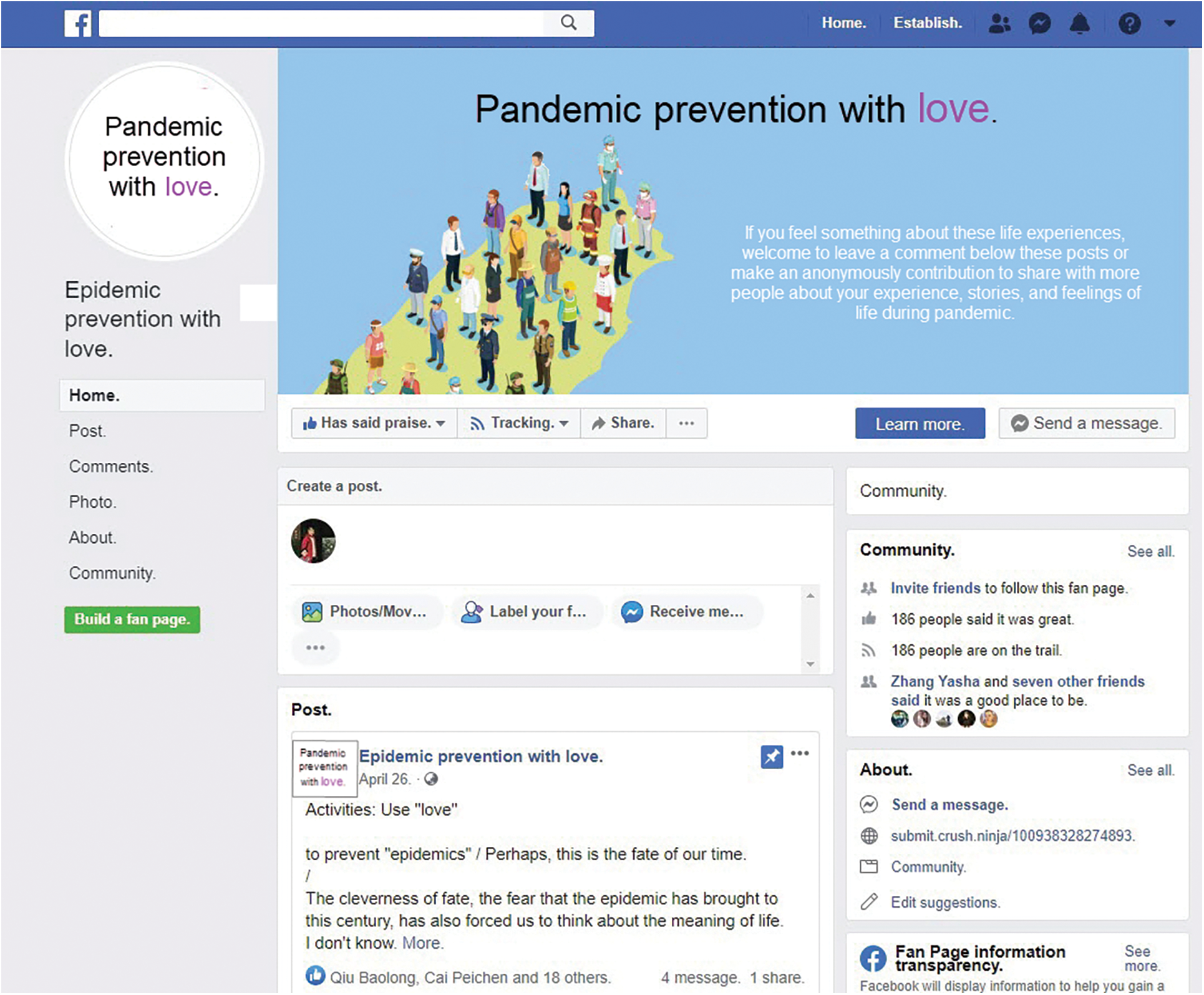

2.2 Pandemic Prevention with Love

(1) Purpose: Virtual community members were guided to think and talk about their life experiences during the pandemic through this platform. Members learned to respond to others’ situations with no judgement to strengthen mutual help.

(2) Function: The counseling team established a second virtual communication platform that targeted the needs of quarantined individuals, which was called “Pandemic prevention with love” (Fig. 3). In this group, anyone could respond to a post or talk about their own quarantine experience. In addition, people could express their feelings about posts, such as by liking or responding to them. In this process, people had the opportunity to see others’ experiences and reflect on their own situations. They could also learn together through care and participation.

(3) Operation model: Everyone in the group was undergoing different situations, and personal self-help was provided as assistance according to these individual situations. Consequently, in the group’s operation, the counseling team utilized diary writing and psychoeducation simultaneously to improve the group’s ability to engage in self-help.

1. Diary writing: The quarantined individuals were invited to document their daily moods and lives. Approximately 20 people accepted the invitation to write a diary entry every day. The diaries were the medium for the researchers and quarantined individuals to communicate with and give each other company. Adequate counseling was also provided for those in quarantine. In addition, those with superior psychological strength were selected by the researchers according to their stories. They were encouraged and instructed to become supporters or sharers in the group (model learning). They had the opportunity to validate their own abilities and recover in the process of helping others, which is another reference to the processes of self-help and mutual help, respectively.

2. Psychoeducation: The team focused on nurturing psychological states in the initial stage of quarantine (April 20). Self-energy was improved, and self-help was achieved through education on relief and recovery. Education on relief mainly provided quarantined individuals with methods, such as regular life activities, activities that make people feel capable, and encouragement to have contact with people to relieve loneliness, to settle their mind and body. The recovery education process focused on nurturing self-conversation, reflection on interpersonal relations, and connection with the support network. Recovery ability was accumulated through maintaining elastic thinking, understanding the role of every actor, encouraging each other, and establishing objectives to execute together.

3. Support groups and strategy utilization: To deepen the group’s ability to provide mutual help, offer company to peers, and encourage people to participate, several strategies were adopted in the operation process.

(1) People who had been diagnosed and quarantined were invited to anonymously share their life conditions and feelings during the quarantine period. This method allowed the self-health managers to understand the situations of the people in quarantine through their stories. It also allowed the quarantined individuals to share their diaries.

(2) Different groups, including people outside the military, soldiers training in foreign countries, and students throughout the school, were invited to write down and share their life experience. Thus, support groups were formed. After the groups read each other’s diaries, those who had feelings they wished to express could share their own experiences or thoughts, such as what influence the pandemic has had on their work, family, and lives.

(3) Group members were encouraged to observe others’ life experiences and write their personal feelings or respond to others’ shared experience (with nonjudgmental language).

Figure 3: The “pandemic prevention with love” Facebook group

Overall, diaries and education were methods that improved people’s self-help abilities. The quarantined individuals were allowed to participate in the mutual help processes to foster connections, company, and sharing via the virtual counseling network. Thus, the quarantined individuals could participate together and feel each other’s support, learning, and growth.

3 Findings from the Practical Operation Process: Transformation from a Broken Group to Collective Healing

In this study, analysis was conducted on the data, diaries, and interviews found in the virtual counseling network. Research has shown that support and companionship are crucial to the healing process of members of a group participating in a virtual counseling network. From the perspective of resilience theory, an individual’s capacity for positive adaptation in facing difficulties (resilience) lies in three protective factors, namely “I have,” “I am,” and “I can.” “I have” refers to external support and resources; “I am” refers to an individual’s strengths and self-confidence; “I can” refers to an individual’s interpersonal skills [6]. Similarly, Seligman [7] noted that an individual’s resilience process consists in having self-confidence and obtaining strength from “I am”, “I have” to “I can”. Accordingly, the operation process of a virtual counseling network involved four major themes of experience: the collective healing of togetherness, empathy, confidence, and belonging and cohesion, which are explained in the following subsections.

Research has emphasized that remote care through the Internet can alleviate anxiety and uneasiness during the quarantine period [8,9]. In addition, individuals were encouraged to use social media to connect with friends and family to avoid loneliness [10,11]. This study found that this method can indeed reduce uneasiness in an individual’s quarantine period. However, the virtual network also promoted another form of connection that allowed quarantined individuals to generate feelings of company, support, and value. Such feelings are core experiences for quarantined individuals, and this connection has not been mentioned in previous literature.

For the quarantined individuals in the counseling network, the feeling of “togetherness” had diverse dimensions and levels. At the personal level, the company and support of the counseling team was provided to the quarantined individuals every day through the online diary-writing process. The quarantined individuals felt that there were people they could talk to and rely on, which created a sense of togetherness. In other words, the quarantined individuals had the opportunity to talk about their real feelings, current moods, and opinions on the pandemic with the researchers every day during the quarantine period. Because of the influence of the strong sense of professionalism of the soldiers, military members often dare not reveal their psychological states in counseling or express personal opinions through an Internet platform. However, because of the anonymity afforded by our platform, the participants were mostly strangers. It was easy for the participants and quarantined individuals to let go of these constraints of being soldiers and express their personal internal feelings boldly and sincerely. This phenomenon is unprecedented in face-to-face counseling. For example, one quarantined individual said the following: “We were always taught to conceal our emotions. However, in urgent situations, I feel we should express ourselves truthfully. Maybe the method of writing a diary can allow us to have a way to understand our own opinions regarding such emotions instead of just ignoring them.”

“Togetherness” entails a collective participation process. Quarantine imposes limits not just in terms of the physical environment; it can transcend the limitations of rank and space. The emotional interaction between “seeing and being seen” and “caring and being cared for” were experienced via the Internet platform. In other words, the platform was an opportunity to escape the limits created by the stratification and stigmatization of military counseling. Such problems (e.g., counseling being limited according to rank) are difficult for traditional face-to-face counseling to overcome. For example, one quarantined individual said the following: “It was the first time that I felt what entanglement is. Many seniors who already graduated commented to cheer us up… and I never thought the entanglement between classmates was so close. We must stay together and move forward. After I read the sentences on the message board, I didn’t feel alone anymore, even though I was quarantined alone.” The regular participants also expressed that although they were not soldiers, they were deeply thankful and grateful for the soldiers’ hard work in the process of mission execution. The civilians and other non-quarantined individuals expressed their hope that the quarantined individuals would believe in themselves and properly rest during the quarantine period. For example, one person said the following: “No matter what, you completed a difficult mission abroad for the country with no fear of the pandemic. Thank you. I hope you are all safe”.

Empathy emerges from a process in which a subject consciously makes puts himself/herself in the other subject’s shoes, allowing for mutual connection and understanding between two subjects with entirely different existential gestures or visions [12]. However, In the initial stages of the incident, some of the soldiers exhibited a phenomenon, namely contradicting emotions in the military group, in the semiofficial Line group. This phenomenon resulted in disputes within the group (e.g., doubt created by the pandemic prevention measures or the psychological states of quarantined individuals) and contributed to a diverse range of different voices. The fear of the disease was projected onto the quarantined individuals by the media. Throughout the pandemic, the public has been shown to misunderstand and stigmatize quarantined individuals, which has resulted in psychological pressure on the quarantined individuals. For example, one quarantined individual said the following: “It hurts. It is slowly beginning. Do you understand? Look at the media speculation. Some of it is not true.… I watch other people throw mud at me, but I can’t defend myself”.

Notably, the researchers also found that the diaries revealed not only the negative psychological states of the individuals in quarantine but also their desires for their personal lives. They wanted the military community to understand and support each other. The virtual counseling network played a crucial role of fostering connection, and those in quarantine were given the opportunity to hear understanding voices from multiple places.

The first level of understanding was from the individuals being cared for and valued by people in society. The attention of the public was triggered through advocacy activities, and they hoped for the destigmatization of the disease. In addition, the power of support was introduced to the quarantined individuals. For example, one person told the quarantined individuals as the following:

“It must be hard for you. Don’t be hurt by some people’s words due to their anxiety caused by the pandemic. This is because they still can’t face the pandemic peacefully. What you didn’t hear is more voices from people who support you. We know that this is not your fault, so don’t blame yourselves. We must face the pandemic together and do what we can to protect each other. Hang in there. You are not alone”

Another person in quarantine said the following: “Many people are speaking in support of us on the Internet. I am really thankful for these people because we (soldiers) can’t say it ourselves. Our messages may also have difficulty gaining approval” Next, when the power of support slowly expanded and became a factor protecting the people in quarantine against self-doubt, the quarantined naval soldiers had the opportunity to calm their minds and clear their thoughts by writing diary entries. In addition, they thought about what they could do in a limited physical environment to actively care for each other. Finally, the virtual group platform allowed the people in quarantine the opportunity to express themselves and gauge each other’s experiences. This process allowed those in quarantine to slowly move away from the role of paying attention to oneself to being an observer of possible reactions when others encounter a critical incident. They could also think about how they would respond to the others’ crises if they were to encounter them. This experience involves introspection from multiple roles and positions as well as the process of understanding each other. For example, one quarantined individual said the following: “There are some points in some places that I did not think about. After seeing them, I thought yeah, there is this direction too. Then, I started to think about it. It functions as a reminder. It tells me that this method also exists”

Recently, scholars have suggested that self-confidence plays a crucial role in recovery during the pandemic. Self-confidence represents one’s spiritual power and positive attitude and is essential in facing infectious diseases (such as COVID-19) and noninfectious diseases (such as depression; Hannan et al. [13]). Self-confidence is developed when people perceive an improvement in their importance and abilities. Psychological consultation, social support, spiritual connection, and eating habits contribute to building self-confidence [13]. Under the collective discipline and regulations of the military, one’s performance in the group can be validated through mutual help in life and in missions. However, collective action with missions and clear goals were suddenly replaced with isolation. For the people in quarantine, the initial stages of the disease and quarantine generated anxiety and confusion for their futures. For example, one person in quarantine said the following: “I felt extremely helpless, angry, sad, and upset. My hands couldn’t stop shaking due to fear and helplessness. I had mixed feelings with no direction for the future”

Because of the soldiers’ self-doubt and decreasing confidence in the initial stages of quarantine, the quarantined individuals were glad to hear each other’s voice through the virtual support community. In addition, everyone had the opportunity to try their best to help others. Observations of interpersonal interactions in the diaries and group platforms revealed that any person in quarantine could help others without the limitation of rank; for example, one individual shared the following in a diary entry: “I write every day to heal myself. I also write for people around me.” One person in quarantine recorded encouragement for an officer: “I shot a video for my captain. I hope that (he) will feel better today.” Those who are in quarantine at home could also perceive their self-value through sharing their experiences on the virtual counseling network. For example, a quarantined individual said the following: “The closer it gets to the time to return to Taiwan, I have more complicated emotions. I expect society to go through the phases of panic, helplessness, and mutual accusation and gradually develop into a united society with mutual understanding, care, and help. I deeply believe that everyone is able to feel empathy. We just need time to deal with the fear inside.”

After detailed observations, the phenomenon of confidence that was resurrected was inferred to be based on “listening” in a safe environment. People had the opportunity to listen to each other’s thoughts in the peer support system. On the virtual platform, people had the opportunity to see diverse experiences as well as to truthfully express their opinions in a safe environment in the process of writing in their diaries and “being seen.” They found advantages and empowerment over time. Thus, they were invited to share their experiences on the virtual group platform and show their gratitude for other people using technology. This process is based on the “sense of togetherness” that existed in the supportive atmosphere of the virtual counseling network. Furthermore, although everyone faced different issues, this platform was based on reciprocity. People first help themselves before helping others, which increased personal value and validated feelings through actual measures.

3.4 Group Belonging and Cohesion

Members in virtual communities form a community spirit and community emotions through interrelated network connections and mutual support. This gives rise to a sense of belonging and cohesion [14]. In this study, the sense of belonging and cohesion created during the operation of the virtual counseling network was not expected. Two key factors were considered to be the reasons for such an effect: the quality of the soldiers’ character and crisis management after quarantine. Soldiers are responsible for protecting their country. However, upon returning to Taiwan after a mission, some soldiers were diagnosed with COVID-19. Everyone suspected of infection was required to undergo at least 14 days of quarantine. This generated severe self-blame when the soldiers thought about their family, friends, and the public. It even created doubt about their identity. In addition, the military leader was placed under investigation to determine accountability. At that time, the public and the media were characterized by doubt over the necessity of the mission as well as calls for a review of military pandemic prevention measures. The abovementioned factors generated psychological shock (such as contradiction and identity crises) for low-ranking soldiers because of their identities on missions. Such shock did not disappear during their physical isolation. For example, a quarantined individual said the following in the initial stages of the quarantine: “This is a feeling of losing a war. This is a feeling of not being happy with being in a witch hunt. This is a feeling of being on the chopping board. We all know that tomorrow will be worse.”

However, in the virtual counseling network, the quarantined individuals helped themselves by writing diaries and further participated in the mutual-help process on the social platform. They realized the power of support from different places and the similarities between their conditions and others’ situations. This generated a sense of belonging. One quarantined individual went from feeling as though part of a broken group to approval and gratitude over the entire quarantine journey:

“We as a group had the feeling of being broken into pieces. The entire group fell apart…. However, you also found that some people were willing to spend even just 30 s to write one paragraph. I think that if people are all willing to give, they are still worthy of being approved of and thanked.”

Next, the collective characteristics of soldiers and the complementarity of the virtual counseling network were beneficial for fostering feelings of collective belonging and cohesion among the soldiers. Before the quarantine, the soldiers could see each other face to face. However, in a mission-oriented group, soldiers do not necessarily have the chance to express their emotions. In the virtual counseling network, the individuals’ self-expression and mutual learning were not limited by the physical environment and identity before quarantine. In addition, the quarantined individuals were engaged in a collective virtual environment involving personal identity reflection and collective writing and participation. Thus, they deeply perceived self-value and collective emotional connections. Moreover, in the process of identity transformation through the quarantine and over time, the individuals transformed from the roles of victim to learner to actor. Specifically, the group of soldiers had the opportunity to re-examine a soldier’s role, ability, professional recognition, and self-expectations in the military. One quarantined individual recalled the feeling in those days: “I went from not understanding in the beginning to finally understanding everyone’s thoughts. I found that everybody considered themselves and thought from their own perspectives. So, if I must face others or become an officer of a unit, I should have a broader view and listen to opinions from every aspect.”

From the collective level, the belonging and cohesion generated during this process are the effects triggered by the accumulation of togetherness, empathy, and confidence.

4.1 Counseling Work Intention Behind the Collective Healing of the Military Community

Currently, the concept of mutual help and support is widely applied to groups such as for persons with HIV (e.g., Hay et al. [15], Laurence et al. [16]), indigenous people (e.g., Heilbron et al. [17]), and men who have experienced violence (e.g., Edström et al. [18]). Studies have also demonstrated that by building and developing peer groups for mutual aid, a safe space can be built for the aforementioned groups. This can allow them to share their experiences in coping with their difficulties without being criticized or criticizing others and can reduce the impact of negative labelling. However, existing military counseling still applies general interventions, and group mutual assistance within military organizations is still in its infancy [19]. Notably, mutual help emphasizes the characteristics of group life and mutual assistance among peers in the military to a certain degree. However, little in-depth research has been conducted on the issue of mutual help among peers. The counseling methods for addressing soldiers’ collective needs often focus on individual misadaptation or trauma. Through personal counselling, individuals are assisted in restoring their interpersonal interaction function. In contrast, this study found that the collective healing perceived by the military community during quarantine is based on the processes of self-help and mutual help. “Togetherness” was the most basic experience of the virtual military community, but it was a critical source of psychological energy. It helped people continue moving forward and not feel alone. The community was based on reciprocity, and everyone faced different issues during the quarantine period. However, they could feel the support of companions. This support, in addition to proper external support, can potentially make people more willing to reflect on their identity and recognition as a soldier. Such support may be more influential than traditional individual counseling, and it helps people overcome the stigma associated with mental health and rank issues for soldiers.

4.2 Operation Issues Regarding the Virtual Community Counseling Network

Virtual communities allow groups to share and develop common interests [20]. This helps people build and maintain interpersonal relationships and establish a supportive network [21]. However, the military virtual community counseling network was a platform that was established temporarily. Furthermore, the virtual community was connected by two levels. The provided platform and associated self-help measures were introduced by the counseling team. Thus, the existing support group could overcome the limits imposed by the quarantine measures.

In fact, the execution process was extremely challenging, and these difficulties were particularly influenced by the limitations of the time factor and heightened level of emergency of the incident. This virtual counseling network was only conceived by the researcher. The possibility of interdisciplinary mutual help via cooperative support must be considered before another crisis occurs in the future. As suggested by Chiu et al. [22], a social worker conducting a crisis intervention must first understand the organization’s operational structure and characteristics and make good use of its resources so as to command, integrate, and provide resources within the shortest time possible. Furthermore, social workers who work in the public sector or organizations must be attentive to the impact on individuals or the environment due to the positions or classes involved. At the same time, they must understand the organization’s network ecology and the respective characteristics of the department in the work unit. In this way, they can complete resource assessment and inventory within the shortest time possible, which allows them to provide diverse services according to individual needs. Admittedly, it was found that in this incident, the healing generated by the quarantined individuals in the virtual counseling network did not require excessive interventions from social workers. The functions of self-help and mutual help could be used on the platform, which had always been neglected by past counseling methods. This also indicates that future social workers require more advanced Internet operation techniques and knowledge to strengthen the counseling efficacy of the Internet platform.

Finally, assistance for groups in the past focused on face-to-face services. Team cohesion may be transmitted through advertising or information. However, this study found that cohesion is triggered by the processes brought about by togetherness, empathy, and confidence. This phenomenon is worthy of attention, particularly in the pandemic or post-pandemic eras. Physical isolation has become a fact of life, and such isolation is not just isolation from disease but also isolation within regional boundaries. Because of the advancement of the Internet world, counseling and support systems in virtual space or the operation of virtual teams must be considered for the future. This study has shown that collective cohesion and psychological healing can be achieved through a virtual community.

The virtual counseling network was a support and companionship network mainly used for military personnel. In terms of service costs, the cost required to deliver traditional services was eliminated. In terms of service time, the service and responses were managed and provided rapidly, and accessibility was effectively improved. In terms of influence, the privacy and anonymity of the virtual counseling network provided soldiers a chance to reflect on the relations amongst themselves and others in a safe space, allowing them to start to recover. In addition, the operation process of the virtual counseling network implied to individual soldiers with negative attitudes that they would fail to adapt to the environment and must be abandoned. Contrarily, interventions focused on interpersonal interaction and support between systems must be further studied and advocated for in the future. This method of mutual help and cooperation can promote collective healing in the military, and thus, it can improve the ability of the entire military to recover.

This study had several limitations. First, it primarily recorded and analyzed the process and therapeutic effect of the virtual counseling network; individual recovery was observed by means of the network data of the program in which quarantined persons participated as well as their diaries and interview texts. Future studies should use an experimental design or summative assessment to better examine the supportive effects of the virtual counseling network. Second, the virtual counseling network was implemented for the first time, and had limited resources and staff available. Finally, it is recommended that practitioners or researchers adopting this program in the future first grasp the operation mode of the target organization or institution and customize the program to suit their needs.

Acknowledgement: I thank Prof. Yu Yi-ming for his encouragement and suggestions. I thank Dr. Teng Chi-ming for his input on the profession and practice of social work. Additionally, I would like to thank all the students who took this course. Also, I truly appreciate that Chang Chi-chun and Wang Yi-ting helped me with the operations of the learning platform.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive any specific grant funding from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This research did not involve Human Subject Research because it was conducted in an educational setting.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Parmet, W. E., Sinha, M. S. (2020). COVID-19—The law and limits of quarantine. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(15), e28. DOI 10.1056/NEJMp2004211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Denckla, C. A., Gelaye, B., Orlinsky, L., Koenen, K. C. (2020). REACH for mental health in the COVID19 pandemic: An urgent call for public health action. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1762995. DOI 10.1080/20008198.2020.1762995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. World Health Organization (2020). Community-based health care, including outreach and campaigns, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/community-based-health-care-including-outreach-and-campaigns-in-the-context-of-the-covid-19-pandemic. [Google Scholar]

4. Brown, M. T., Landrum-Brown, J. (1995). Counselor supervision: Cross-cultural perspectives. Handbook of Multicultural Counseling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

5. Forbes, D., Pedlar, D., Adler, A. B., Bennett, C., Bryant, R. et al. (2019). Treatment of military-related post-traumatic stress disorder: Challenges, innovations, and the way forward. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(1), 95–110. DOI 10.1080/09540261.2019.1595545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Groberg, E. (1995). A guide to promoting resilience in children: Strengthening the human spirit. Hague, Netherlands: The Bernard van Leer Foundation. [Google Scholar]

7. Seligman, M. E. (2011). Building resilience. Harvard Business Review, 89(4), 100–106. [Google Scholar]

8. Liu, S., Yang, L., Zhang, C., Xiang, Y. T., Liu, Z. et al. (2020). Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), e17–e18. DOI 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Xiang, Y. T., Yang, Y., Li, W., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q. et al. (2020). Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(3), 228–229. DOI 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wesseley, S. et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. DOI 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Fiorillo, A., Gorwood, P. (2020). The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. European Psychiatry, 63(1), e32. DOI 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Cheng, Y. S., Shiao, T. C., Chang, M. L., Chou, C. Y. (2015). Cross-over and empathy: A phenomenological research on peer service experience of the wrap around program in Taiwan. NTU Social Work Review, 31, 165–216. DOI 10.6171/ntuswr2015.31.04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hannan, M. A., Islam, M. N., Uddin, M. J. (2020). Self-confidence as an immune-modifying psychotherapeutic intervention for COVID-19 patients and understanding of its connection to CNS-endocrine-immune axis. Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Experimental Therapeutics, 3(4), 14–17. DOI 10.5455/jabet. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Iriberri, A., Leroy, G. (2009). A Life-cycle perspective on online community success. ACM Computing Surveys, 41(2), 1–29. DOI 10.1145/1459352.1459356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hay, K., Kwardem, L., Welbourn, A., Namiba, A., Tariq, S. et al. (2020). “Support for the supporters”: A qualitative study of the use of WhatsApp by and for mentor mothers with HIV in the UK. AIDS Care, 32(Sup2), 127–135. DOI 10.1080/09540121.2020.1739220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Laurence, C., Wispelwey, E., Flickinger, T. E., Grabowski, M., Waldman, A. L. et al. (2019). Development of PositiveLinks: A mobile phone app to promote linkage and retention in care for people with HIV. JMIR Formative Research, 3(1), e11578. DOI 10.2196/11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Heilbron, C. L., Guttman, M. A. J. (2000). Traditional healing methods with first nations women in group counselling. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 34(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar]

18. Edström, J., Dolan, C. (2019). Breaking the spell of silence: Collective healing as activism amongst refugee male survivors of sexual violence in Uganda. Journal of Refugee Studies, 32(2), 175–196. DOI 10.1093/jrs/fey022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Dragonetti, J. D., Gifford, T. W., Yang, M. S. (2020). The process of developing a unit-based army resilience program. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(9), 1–9. DOI 10.1007/s11920-020-01169-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wasko, M. M., Faraj, S. (2005). Why should I share? examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 35–57. DOI 10.2307/25148667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ridings, C. M., Gefen, D. (2006). Virtual community attraction: Why people hang out online. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(1), 1–10. DOI 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00229.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chiu, P. L., Yu, Y. M. (2021). Resilience and COVID-19: Action plans and strategies in a military community. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Developent, 31(1–2), 115–122. DOI 10.1080/02185385.2020.1828156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |