| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.019734

ARTICLE

How Urban Public Service Affects the Well-Being of Migrant Workers: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Theoretical Perspective of Social Comparison Theory

1Faculty of Education, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, 650500, China

2School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

3Department of Psychology, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, 4331, Bangladesh

4Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington DC, 20052, USA

5Department of Economics, Sheikh Hasina University, Netrokona, 2410, Bangladesh

*Corresponding Author: Keli Yin. Email: yinkeli@ynnu.edu.cn

Received: 11 October 2021; Accepted: 19 November 2021

Abstract: Government city management is facing higher requirements with the development of the number of migrant workers. Therefore, improving their subjective well-being is a significant practical problem that the government must consider in public governance. This research discusses the influence of public service satisfaction on the well-being of urban migrant workers from the perspective of social comparison theory and the role of the sense of social equity and social conflict in the process of this influence. Using the structural equation modeling and moderated mediating mechanism analysis, the results show that: (1) the satisfaction of social and economic public service significantly and positively affects subjective well-being. (2) The sense of social equity completely mediated the influence of the satisfaction of public social service on well-being and partly mediated the influence of the satisfaction of public financial service on well-being. (3) The sense of social equity and conflict have a moderated mediating effect for social and economic public service satisfaction on well-being. Finally, the article concludes with some suggestions to improve the well-being of migrant workers based on the conclusion of the study.

Keywords: Urban migrant workers; satisfaction of public service; subjective well-being

Currently, China is in a rapid urbanization, where a considerable number of city migrant workers play the key role in this development. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the total number of migrant workers in China has increased every year for the last couple of decades. In 2020, approximately 285.60 million migrant workers were employed, and 45.87% worked in cities [1]. Often a crucial question is raised regarding the survival status of this alien group. A comparative study showed that the well-being of urban migrant workers in China is considerably lower than their rural counterparts. This is especially the case for new the generation of migrant workers, who are described as “rural deserters, urban lone birds”, who grew up far removed from rural life, working in urban areas for a living and as such may experience different psychology. Thus, the well-being of this increased urban migrant worker population has become an unavoidable challenge in modern urban management. The research about improving the well-being of migrant workers is mainly focused on two aspects. Firstly, some literature has explained how objective external indicators (absolute income, relative income, welfare acquisition, etc.) influence subjective well-being [2,3]. Although defining objective external indicators are difficult, they have been shown to influence subjective well-being [4]. The objectivity effects the subjective well-being by signifying the circumstantial goods [5]. However, not all external indicators are the same in terms of their influence on subjective well-being; therefore, external indicators need to be prioritized. Second, previous literature has focused on the influence of subjective psychological factors (social exclusion, social support, rights and interests protection, motivation for achievement, etc.) on the well-being of migrant workers [6–11]. However, most of these previous studies focused on the individual or familial aspects to explain the well-being of migrant workers, where the role of social factors was less studied, especially for those working in the public service and how that environment is influential to well-being. Thus, exploring and determining ways to more effectively support and resolve poor well-being for migrant workers in urban settings is important as doing so will help to improve the quality of urbanization and gradually transform such psychological challenges for current and future generations. While integrating with the urban settings, migrant workers encounter psychological distresses that should be addressed by their respective concerned government departments. The psychological distress of migrant workers induced by socio-cultural dissonance has a far-reaching negative impact on their well-being. Therefore, social factors such as satisfaction with public services, sense of social equity, and migrant locals’ social conflict may significantly negatively affect the well-being of migrant workers. Considering this issue, this present study focused on the influence of public service satisfaction on the well-being of migrant workers along with the role of sense of social equity and social conflict, in China. In this study, the meaning of urban migrant workers refers to: Persons with registered agricultural registration status but engaged in secondary and tertiary industries in cities and towns and who obtain wage income. This study was carried out empirically, based on the theory of social comparison and related literature. The study used the data from the 2013 Chinese National Household Survey [12] for analyzing the influence of public service satisfaction on the subjective well-being of migrant workers and the role of social equity and conflict in this process. Later in the recommendations section, suggests the relevant government departments who can help to subsequently formulate effective public policy.

2.1 Theoretical Foundation and Hypothesis

Subjective well-being is an essential psychological measure of people’s quality of life. It is anticipated that government can influence public well-being by changing external living conditions. It can be said that the quality of public governance is closely related to people’s well-being. Access to good public services often leads to greater well-being, such as good air quality [13,14], sound social security and distribution systems [15], low inflation and unemployment [16], and access to benefits [17]. Conversely, the lack of public services often leads to lower levels of well-being, such as unemployment, cost-of-living pressures, and social and environmental problems. Migrant workers are eager to live and work in the city as doing so can offer a wider range of opportunities, food and clothing options, and other aspects of the government such as more accessibility to public services. Therefore, we propose that:

H1: the satisfaction of public services for urban migrant workers positively influences subjective well-being;

Public well-being in developed and well-public serviced areas may not necessarily be higher than in more rural areas. The China Urban Competitiveness Research Association released a list of the happiest cities, first-tier cities such as in the north were ranked later on the list. On the contrary, some financially underdeveloped urban residents were found to be happier [18]. The Easterlin Paradox of economics found no significant difference in happiness levels between rich and developing countries [19]. Adam Smith has long pointed out that the well-being of workers comes from social progress, not from the peak of social wealth [20]. When there is social stagnation or regression for all sectors of society it can be filled with hardship and little pleasure. In recent years, academic circles have realized that happiness can come from comparison, and the criteria used for such comparisons are subjective and dynamically adjustable, making one’s well-being just as relative [21]. Campbell believes that people will be happier if they improve their current situation compared to another person in the past [22]. Social comparison theory points out that people will make judgments with relative positions in mind (i.e., they have to have a comparative frame of reference before feeling judgment), which may help to solve the mystery of happiness [23].

Based on social comparison, we believe in analyzing the impact of public service satisfaction on happiness. In this regard, equity should be considered because public services would likely promote social equity and thus happiness, as it is viewed through a fair subjective experience comparison. Studies have found that higher levels of inequality are related to lower happiness levels among the general public; for example, income inequality [24,25] and social inequality, negatively correlated with happiness [26–28]. This has also been confirmed in Chinese studies [29,30]. Based on the current situation of urban migrant workers in China, although the overall level of public services in China has proliferated in recent years, the gap accumulated over the past is greater. The current Chinese public services cannot keep up with the rate of urbanization [31], which means that tens of millions of urban migrant workers cannot enjoy the same public services as urban citizens. Data show that China’s urbanization rate reached 51%, and yet the only 36% of that includes access to urban public services; the remaining 15% of the rural-urban population, cannot enjoy the same public services and social security in a “semi-urbanized” state. Therefore, migrant workers often become marginalized urban “quasi-citizens” and such feelings of social inequality can negatively impact their well-being. Therefore, we propose that:

H2: The sense of social equity of urban migrant workers positively influences subjective well-being;

H3: The sense of social equity mediates the relationship between the satisfaction of public service and subjective well-being.

The experience of the integration of immigrants from all over the world demonstrates that the social integration of new immigrants is a long and enduring process. Gans’ theory of curvy integration suggests that even second-generation migrants may not improve their economic and social conditions in their new social environment and may still be marginalized by mainstream society and not truly integrate into this new social environment [32]. R.E. Park, the founder of the Chicago School of Learning, argues that the integration of immigrant communities consists of four stages: encounter, competition, adaptation, and integration, each of which can lead to the inability to integrate [33]. Due to the system’s construction, resource allocation and other reasons, migrant workers in the process of urban integration can lack access to local, mainstream social life making it difficult to feel equal and accepted, thus protruding a strong sense of “local conflict” between foreigners and locals. For individuals who think that foreigners and locals have a strong sense of conflict, they may often compare with local urban residents because they cannot fully integrate into urban life, the phenomenon of so-called “one city, two circles of life”. Even if the satisfaction of public services is high, it is still easy to feel inequity, so a strong sense of social conflict may weaken the relationship between public service satisfaction and social equity. But for individuals who think that foreigners have a lower sense of conflict with locals because there is less psychological rejection, high satisfaction with public services may bring positive changes in their own lives, so that the relationship between public service satisfaction and social equity will be enhanced. Therefore, we propose:

H4: The sense of social conflict negatively moderates the relationship between the satisfaction of public services and social equity; that is, with the decrease of social conflict, the relationship between public service satisfaction and social equity will be enhanced, and vice versa.

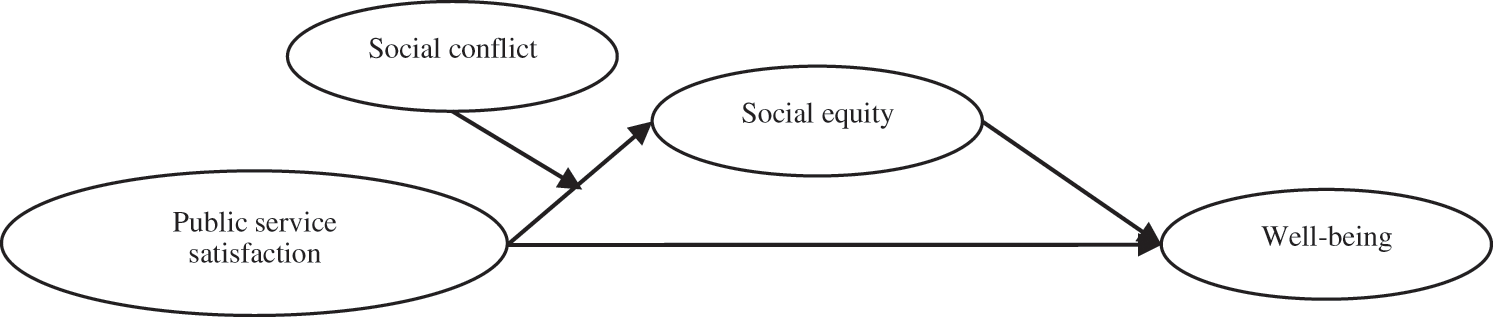

The theoretical model diagram for this study is as follows (see Fig. 1):

Figure 1: A theoretical model of the effects of public service satisfaction, social equity, and social conflict, on well-being

2.1 Data Source and Variable Measurement

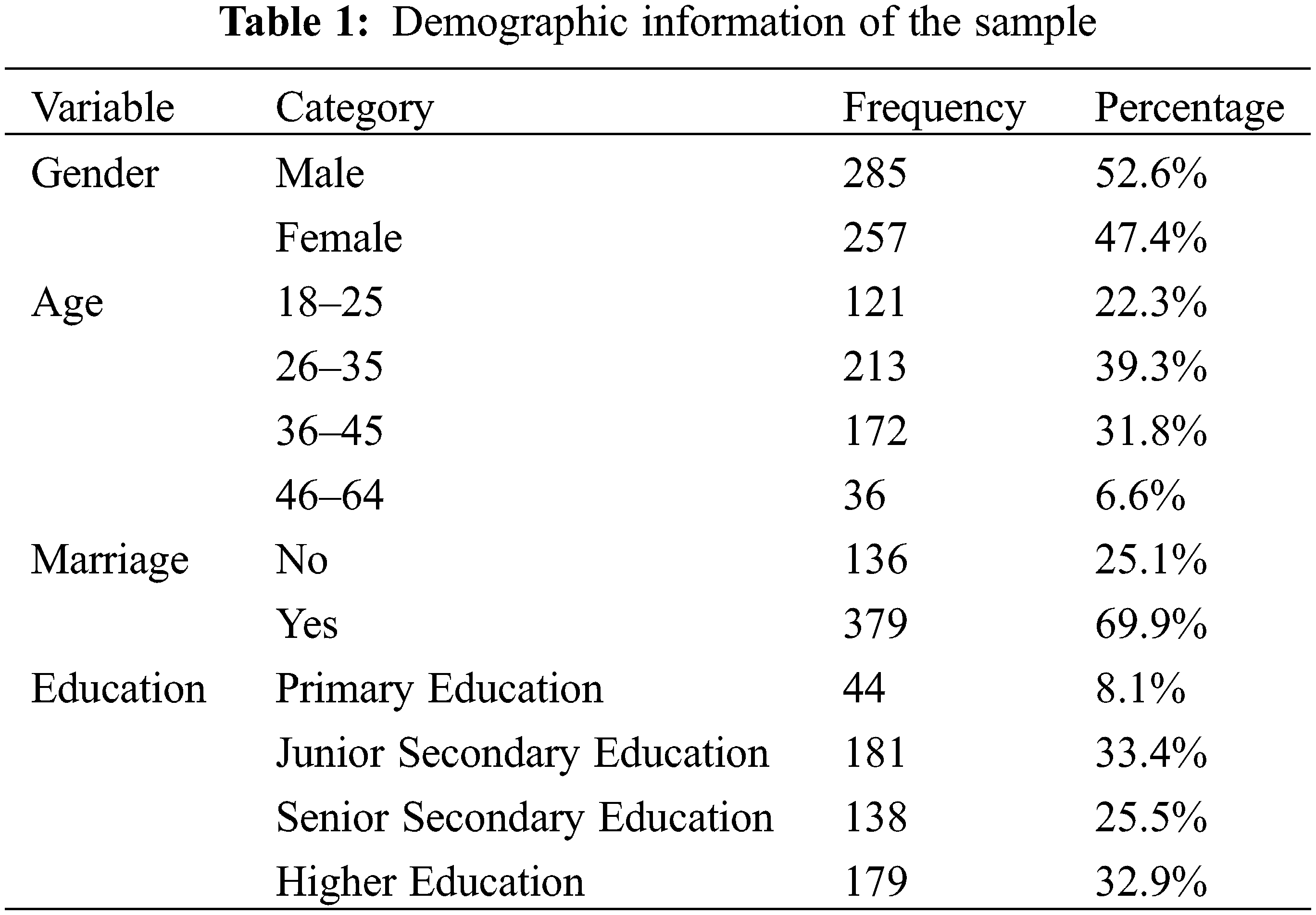

The data used in this present study was collected from the Comprehensive Survey of China’s Social Conditions conducted from April to October 2013 by the Institute of Sociology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences [12]. The survey was conducted in 31 provinces and autonomous regions of the country, covering 151 counties (districts) and 604 residential (village) communities, and interviewed 10,206 urban and rural residents aged 18 and over through probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling, meeting the requirements of statistical inferences. In the survey of urban migrant workers, in the absence of value data, 542 people were in the sample, of which 52.6% of men and 47.4% of women. The participants’ age ranged from 18 years to 64 years (M = 33.10 years, SD = 8.44 years). Detailed demographic characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. The questionnaire design of the relevant variables in this study was confirmed, and the validity was high, which can be used to assess the measures of the relevant variables described.

The dependent variable in this study is subjective well-being. Subjective well-being is defined by Diener [34]; that is, subjective happiness derived from an individual’s life experience and is a positive emotional experience that results from an individual’s evaluation of all aspects of their life. This present study administered the 6-item Chinese Subjective Well-Being scale [35]. Participants rated all items (“My life is very close to my ideal”, “I am satisfied with my life”) on the six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The total scores range from 6 to 36, and a higher total score indicates greater subjective well-being. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.85.

2.2.2 Public Service Satisfaction

The independent variable for this study is public service satisfaction. The respondents were asked to evaluate the satisfaction of the local public service, and each original score is between 1 to 4 points, adjusting the reverse scoring items. The higher the total score, indicating higher the satisfaction with the public service. Through exploratory factor analysis, it is found that the KMO value of the scale is 0.88, Bartlett’ spherical test approximates the square value of the card is 1672.94, and the p < 0.05, which indicates that it is suitable for factor analysis. The results show that public service satisfaction consists of two factors, explaining 58.45% of the variance. The factor I entries include the provision of medical and health services, social security for the masses, compulsory education, environmental protection, and pollution control, fighting crime and maintaining public order, named “satisfaction of social public services”; factor II entries include economic development to increase people’s income, low-cost housing and affordable housing for low- and middle-income people, increased employment opportunities, transparency in government information disclosure, and “satisfaction with economic public services.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.83 for the component table.

The intermediary variable in this study is the sense of social equity. The measurement of social equity includes compulsory education; political rights enjoyed by citizens, justice and law enforcement; public health care, work, and employment opportunities; wealth and income distribution; social security treatment such as old-age care; treatment between different regions and industries; selection of party and government cadres, rights and treatment between urban and rural areas; and overall social equity. Each question’s score is between 1 to 4 points with higher total scores indicating a higher sense of social equity. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale is 0.87.

The regulatory variable of this study is the sense of social conflict. The measure of the sense of social conflict is to evaluate the severity of social conflict between foreigners and locals. The assignment of 1 to 4 points indicates no conflict, less serious, more serious, and very serious, respectively. The higher the score indicates the individual’s sense of social conflict is stronger.

The present study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, this study was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Education, Yunnan Normal University (ERB No. 2021023, date: 2020-12-23).

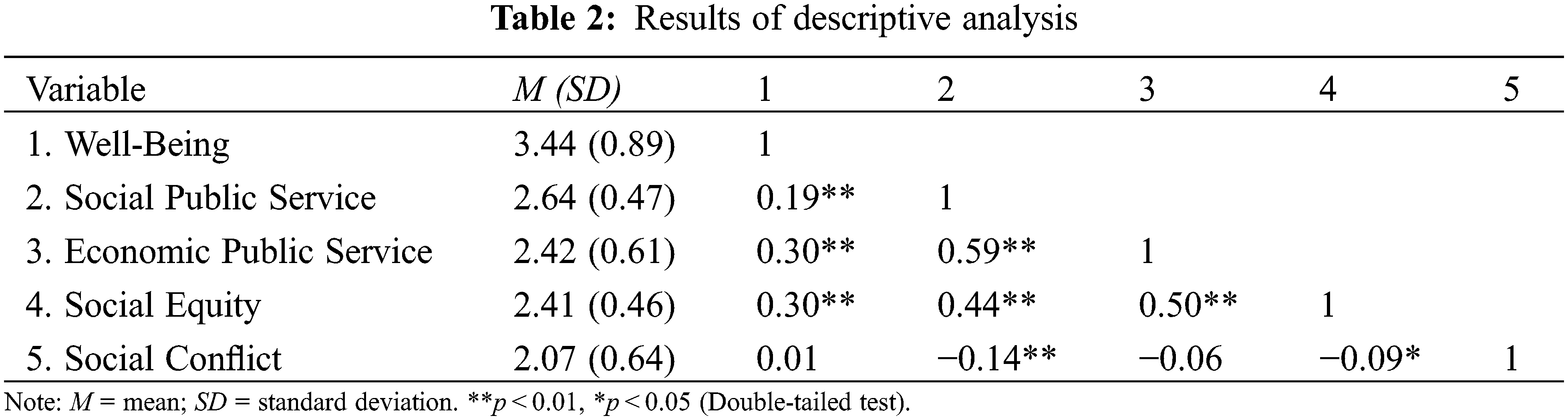

3.1 Descriptive Statistics of the Various Variables

Table 2 shows the average, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients of each variable, satisfaction in both types of public services is significantly related to social equity and subjective well-being, and social equity is significantly related to subjective well-being. This provides the necessary prerequisite for the later analysis of the intermediary effect of social equity.

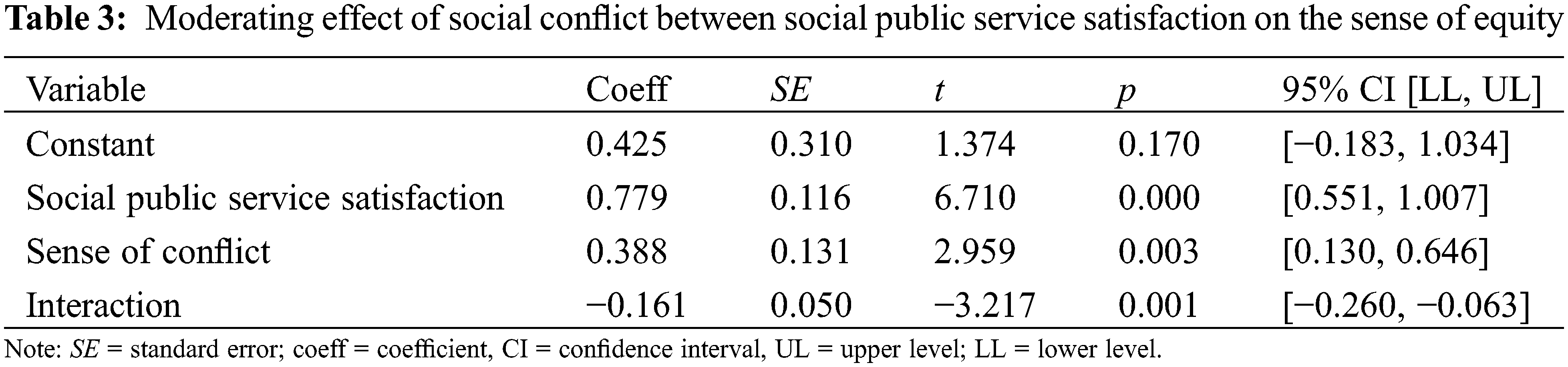

3.2 The Impact of Public Service Satisfaction on the Sense of Fairness: The Moderating Effect of the Sense of Conflict

The process plugin [36] was performed using SPSS 22.0 with reference to the Bootstrap method proposed by Hayes. Model 1, sample size 5,000 was selected, 95% confidence interval. It defined public service satisfaction as the independent variable, sense of fairness as the dependent variable and sense of conflict as the moderating variable. The results of the Bootstrap analysis indicated that, sense of conflict has a significant negative moderating effect between social public service satisfaction and well-being (p < 0.001). It means that when the conflict sense score is low, social public service satisfaction has a large positive impact on well-being (Effect = 0.618, SE = 0.071, t = 8.735, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.479, 0.757]); but when the conflict sense score is high, social public service satisfaction has a less positive impact on well-being (Effect = 0.296, SE = 0.056, t = 5.303, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.186, 0.405]). The sense of conflict has a significant negative moderating effect between economic public service satisfaction and well-being (p = 0.003). This means that when the conflict sense score is low, economic public service satisfaction has a large positive impact on well-being (Effect = 0.486, SE = 0.048, t = 10.132, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.392, 0.581]); but when the conflict sense score is high, economic public service satisfaction has a less positive impact on well-being (Effect = 0.276, SE = 0.041, t = 6.670, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.195, 0.358]). Thus, the hypothesis of H1 was confirmed.

3.3 The Impact of Public Service Satisfaction on Well-Being: The Mediating Effect of Sense of Fairness

The mediation effect test using the process of SPSS 22.0 [36] with reference to the Bootstrap method proposed by Hayes. Model 4, sample size 5,000 was selected with a 95% confidence interval. It defined public service satisfaction as the independent variable, well-being as the dependent variable and sense of equity as the mediating variable. The analysis showed that the direct effect of social public service satisfaction on the dependent variables was not significant after controlling for the mediation variables, with the interval including 0 (Effect = 0.137, SE = 0.087, 95% CI [−0.035, 0.308]), and the indirect effect of the mediation test excluding 0 (Effect = 0.222, SE = 0.046, 95% CI [0.142, 0.318]). The direct effect of economic public service satisfaction was significant on the dependent variables, with the interval excluding 0 (Effect = 0.285, SE = 0.068, 95% CI [0.153, 0.418]), and the indirect effect of the mediation test excluding 0 (Effect = 0.143, SE = 0.034, 95% CI [0.079, 0.212]). Therefore, this result reflects a complete mediation effect of sense of equity in the effect of social public service satisfaction on well-being, and a partial mediation effect for economic public service satisfaction on well-being. Thus, the hypotheses H2 and H3 were confirmed.

3.4 The Impact of Public Service Satisfaction on Well-Being: The Sense of Fairness and Conflict Have a Moderated Mediating Effect

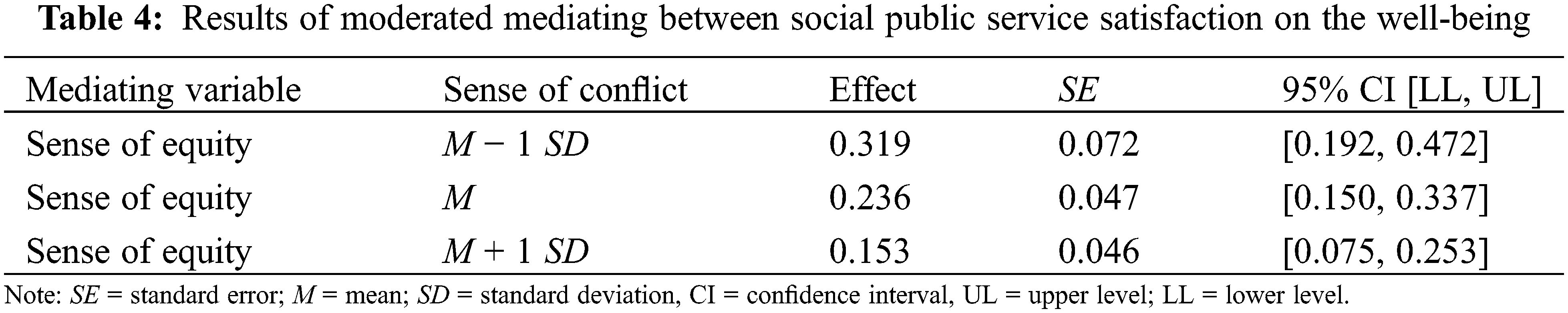

According to the above results, sense of conflict had a significant moderating effect between public service satisfaction on the sense of equity, and the sense of equity had a mediation effect between public service satisfaction on well-being, so the process plugin of SPSS 22.0 was used for a moderated mediating test [36] with reference to the Bootstrap method proposed by Hayes. Model 7, sample size 5,000 was selected with 95% confidence intervals. It defined public service satisfaction as the independent variable, well-being as the dependent variable, sense of equity as the mediation variable, and sense of conflict as the moderating variable.

The results of the Bootstrap analysis showed that the indirect effect of social public service satisfaction on well-being in the mediation test of sense of equity excluding 0 (95% CI [0.342, 0.691]), indicating a significant mediation effect of sense of equity (Effect = 0.516). After controlling for the mediation variables, the direct effect of the independent variables was not significant, and the interval (95% CI [−0.034, 0.309]) including 0, indicating that the sense of equity plays a complete mediating effect between social public service satisfaction on well-being.

At the same time, the mediating effect between social public service satisfaction on well-being through a sense of equity is moderated by the sense of social conflict. When the conflict score is low, social equity has a large mediation effect between social public service satisfaction on well-being, while when the social conflict score is high, the mediation effect is small. The analyses of the results are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

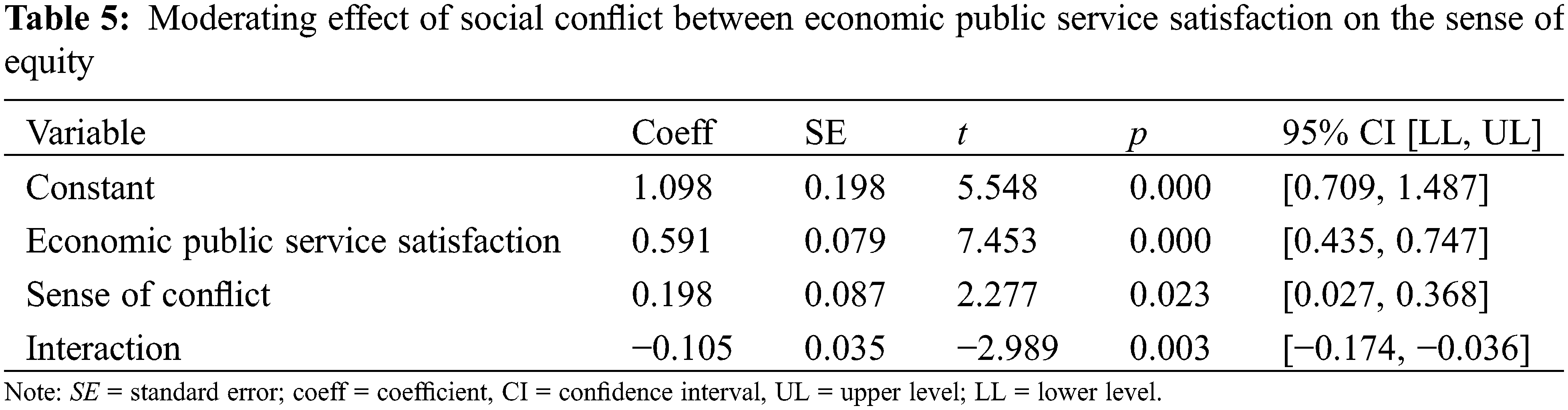

In the effect of economic public service satisfaction on well-being, the indirect effect of mediation test of social equity excluding 0 (95% CI [0.209, 0.565]), indicating significant mediation effect of sense of equity (Effect = 0.387). After controlling for the mediation variable, the direct effect of the independent variable was significant, and the interval excluding 0 (95% CI [0.152, 0.418]), indicating that the sense of equity is a partial mediating effect of economic public service satisfaction on well-being.

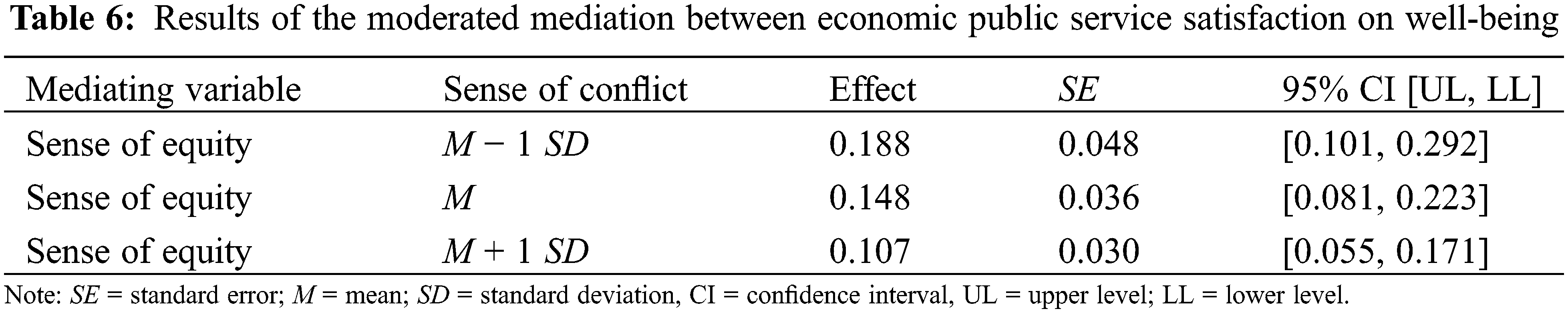

At the same time, the mediation process between economic public service satisfaction on well-being through a sense of equity is moderated by the sense of social conflict. When the conflict score is low, equity has a mediation effect for the effect of economic public service satisfaction on well-being; while the social conflict score is high, the mediation effect of economic public service satisfaction on happiness is smaller. Thus, the hypothesis of H4 was confirmed. The results are shown in Tables 5 and 6.

The main purpose of this paper is to explore the integration process of migrant workers’ subjective well-being from the perspective of social comparison theory. Previous studies have noted that governance has a significant impact on people’s well-being. Still, few studies have explored the role of public service satisfaction of urban migrant workers on subjective well-being. This study found that the satisfaction of urban migrant workers with social and economic public services significantly positively affected subjective well-being, but the influence mechanism was not the same. The influence path of social public service satisfaction on subjective well-being, that is, must be implemented through the complete intermediary of social equity. The influence of economic public service satisfaction on subjective well-being is more complex. Social equity only plays a part in the intermediary role, which is a phenomenon not found in previous research and is an essential supplement to public service literature.

The previous research on the well-being of migrant workers mainly focused on urban public services and individual psychological factors. Urban public services such as living conditions [37], public goods supply [38] are all significantly and positively correlated to migrant workers’ well-being, but some studies believe that the impact of public expenditure on well-being is not obvious [39,40]; moreover, some studies found that different types of public services have different effects on well-being, such as with health insurance or pension insurance being higher than labor remuneration [41]. However, psychologists believe that objective factors are not the only factors that affect well-being [4,42], and that the psychological factors of migrant workers also have a direct impact on well-being. Studies have found that the sense of income equity is lower for urban residents [43], while this sense of discrimination negatively affects the happiness of migrant workers [44]. Reducing income injustice and increasing public service expenditure will significantly increase happiness [45]. Thus, current studies on the influencing factors of well-being gradually converge on the interaction of subjective and objective factors [46]. Some scholars point out that the existing research is too focused on the supply side of public services, and ignore the demand side of public services, making it challenging for public services to effectively respond to citizens’ public service demands [47]. This research confirmed that different types of public services significantly and positively affect the well-being of migrant workers, but the magnitude and mechanism of this effect is not the same. Meanwhile, psychological factors play a moderated mediating effect between public services and the well-being of migrant workers.

We believe that the above results reflect that concept for urban migrant workers as the equalization of public social services is more demanding than public economic services. Given the current situation, urban migrant workers are limited by their own low human capital stock and social resources, in the short term, they are at a disadvantage for achieving and exposure to employment opportunities and income distribution of absolute equity; though, they typically recognize this, so public economic services do not necessarily have to reflect a sense of social equity. As long as their situation improves it should bring about happiness. That said, public social services are entirely different, and because they reflect more starting point equity (e.g., education) and procedural equity (e.g., social security system, legal system construction, etc.), which is their hope for a happy urban life for themselves and future generations, equity plays a decisive role in happiness. Urban migrant workers clearly understand their current situation and limitations, but this does not mean that the government can relax its vigilance, the so-called “cang-truth and etiquette, food and clothing and honor,” government departments still have to work to ensure that urban migrant workers can live a decent life after changing their status, to prevent possible generational poverty and urban slum problems [48]. Otherwise a large number of poor and migrants may evolve into a series of new urban problems.

It is also worth noting that migrant workers will inevitably experience a sense of social conflict in the process of urban integration [49,50]. This study finds that the sense of social conflict will regulate the impact of economic public service satisfaction on the sense of social equity but cannot regulate the impact of social public service satisfaction on social equity. The findings mean that government departments should focus on fairness and justice for social services to improve people’s well-being by reducing the gap between the rich and poor, social discrimination, and so on. But for public economic services, government departments must consider more factors, including equity, because the sense of social conflict will negatively regulate the relationship between public economic services and social equity and further negatively affect well-being; indicating that government departments in their vigorous development of the economy must also pay attention to and work to effectively solve social contradictions and conflicts so they do not intensify.

The enlightenment of this study to public management practice lies in: First, government departments should focus on perfecting the construction of the legal system and grass-roots functional departments and improving the satisfaction of migrant workers with urban public services. In social security, compulsory education, legal construction, and other social public services, government departments should further improve the systemic construction, removing the institutional barriers to the urbanization of migrant workers so that the protection of their rights and interests can occur under law. That said, specific implementation rules should also be explained to ensure the effective implementation of this system change. Moreover, improvements regarding the responsiveness to the interests of migrant workers need to be focused on as well. Labor disputes, wage recovery, and other problems can quickly cause anxiety among migrant workers, so government departments should actively coordinate and help to solve them; for example, this could be done through increasing income, expanding employment, and other economic public services, low- and middle-income migrant workers could be provided with low-cost and affordable housing, and policy can be made to reduce education costs for their children.

Second, the focus should be on improving the sense of social equity among migrant workers. The sense of social equity of migrant workers affects subjective well-being, so helping migrant workers obtain human capital in the city, to live a more fulfilling life can be beneficial. Government departments should increase the policy in favor of migrant workers and pay attention to policy publicity and interpretation to prevent the policy from being misunderstood and misread. For example, some migrant workers think that although their health insurance policy is good, the cost of treatment is rising, more than in the past to see a doctor. Another example: the current migrant worker’s pension insurance coverage rate is not high, which also reflects the policy and creates social inequity. To enhance the human capital stock of migrant workers, providing free of charge vocational skills training opportunities can help restore perceptions of social inequity by creating a fair social environment and reduce the social exclusion of migrant workers’ status as foreigners. In addition, avoiding local and near-earth urbanization can help to reduce the “earth-guest conflict” caused by psychological inequality. Overall, strengthening the education of migrant workers citizens, so that migrant workers can do everything possible to participate in urban construction and cultivate their sense of urban ownership is worthwhile for developing their integration and well-being.

Third, paying attention to the speed of urbanization is important. Some areas of China country appear as so-called empty cities or are ghost towns, partly due to the rapid pace of urbanization. China’s ancient land planning and population distribution, there is a “Tudor, the road is enough to serve its people” principle is representative of this. However, currently, because of the emergence of large cities they have fewer people compared to small and medium-sized cities. On the one hand, we should beware of the rapid expansion of the city “spread cake,” to ensure that the supply of public services can keep up with the pace of population urbanization. On the other hand, the developed cities and towns of the manufacturing industry can attract more migrant workers to settle down according to the demand for labor. For migrant workers, they may be located based in the local conditions their most comfortable with or that give the most opportunity; nonetheless, paying attention to fairness and operability during urbanization is important when considering these workers’ psychological well-being.

This study found that for urban migrant workers: (1) social and economic public service satisfaction positively affects subjective well-being, (2) social equity plays a complete mediating effect of social public service satisfaction on subjective well-being, while economic public service satisfaction had a partial mediating effect on subjective well-being, and (3) the sense of equity and social conflict have a moderated mediating effect for social and economic public service satisfaction on well-being.

The possible shortcomings of this paper are: first, due to the availability of data, the number of survey samples is relatively limited, therefore, follow-up research cannot be done; second, the supply of public services in different cities varies, and it is not compared according to the heterogeneity of different urban scales, which needs to be studied further in future research.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Yunnan Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Youth Project under Grant No. QN2018055.

Conflicts of Interest: This study was carried in the absence of any personal, professional, or financial relationships that could potentially be constructed as a conflict of interest.

1. China National Bureau of Statistics (2020). The Survey of National Migrant Workers Monitoring. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202104/t20210430_1816933.html. [Google Scholar]

2. Fang, J. D., Fu, M. F. (2012). Study on the well-being of the new generation of migrant workers-data analysis based on more than 6000 questionnaires of the new generation of migrant workers. Guangdong Agricultural Sciences, 39(5), 184–187 (in Chinese). DOI 10.16768/j.issn.1004-874x.2012.05.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu, S. G., Liu, R. F. (2012). An empirical research on the index of well-being of young migrant workers and influence factors. Urban Problems, 31(1), 66–71 (in Chinese). DOI 10.13239/j.bjsshkxy.cswt.2012.01.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Voukelatou, V., Gabrielli, L., Miliou, I., Cresci, S., Sharma, R. et al.(2020). Measuring objective and subjective well-being: Dimensions and data sources. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, 11(4), 279–309. DOI 10.1007/s41060-020-00224-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Western, M., Tomaszewski, W. (2016). Subjective wellbeing, objective wellbeing and inequality in Australia. PLoS One, 11(10), e0163345. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0163345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hu, M. J., Peng, W. B. (2011). The relationship among the perceived social support, self-esteem and subjective well-being of contemporary rural migrant workers. Journal of Psychological Science, 34(6), 1414–1421 (in Chinese). DOI 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2011.06.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu, J., Mao, X. F. (2013). The rights and well-being of migrant workers: An empirical analysis based on micro drugs. Chinese Rural Economy, 29(8), 65–77 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

8. Ye, P. F. (2011). Migrant workers’ subjective well-being in urban life: An empirical analysis. Youth Studies, 30(3), 39–47 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

9. Jin, X. T., Cui, H. J. (2013). Research on the relation of new generation of migrant workers’ achievement motivation and subjective well-being. Chinese Rural Survey, 34(1), 69–77 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

10. Chiang, Y. C., Chu, M., Zhao, Y., Li, X., Li, A. et al. (2021). Influence of subjective/objective status and possible pathways of young migrants’ life satisfaction and psychological distress in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 612317. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.612317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Bretones, F. D., Jain, A., Leka, S., García-López, P. A. (2020). Psychosocial working conditions and well-being of migrant workers in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2547. DOI 10.3390/ijerph17072547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chinese Social Survey (2013). Comprehensive survey of China’s social conditions. http://css.cssn.cn/css_sy/. [Google Scholar]

13. Welsch, H. (2006). Environment and happiness: Valuation of air pollution using life satisfaction data. Ecological Economics, 58(4), 801–813. DOI 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Tran, V. V., Park, D., Lee, Y. C. (2020). Indoor air pollution, related human diseases, and recent trends in the control and improvement of indoor air quality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2927. DOI 10.3390/ijerph17082927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Feng, S. (2007). Gender, occupation and subjective well-being (in Chinese). Economic Science, 29(1), 95–106. DOI 10.19523/j.jjkx.2007.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tella, R. D., MacCulloch, R. J., Oswald, A. J. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. The American Economic Review, 91(1), 335–341. [Google Scholar]

17. Sun, Y. T. (2015). Study on the well-being of urban migrant workers based on welfare–use 875 samples in henan province as an example. Northwest Population Journal, 36(3), 43–52 (in Chinese). DOI 10.15884/j.cnki.issn.1007-0672.2015.03.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. China Institute of City Competitiveness (2017). List of the happiest cities in China. http://www.wasa-china.com/yjh/fyphb_show.asp?id = 6550. [Google Scholar]

19. Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In: David, P. A., Reder, M. W. (Eds.Nations and households in economic growth, pp. 89–125. Academic Press. DOI 10.1016/B978-0-12-205050-3.50008-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bragues, G. (2009). Adam smith’s vision of the ethical manager. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(S4), 447–460. DOI 10.1007/s10551-010-0600-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á., Matz, S., Huppert, F. A. (2020). Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 192. DOI 10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

23. Wood, J. V. (1996). What is social comparison and how should we study it? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(5), 520–537. DOI 10.1177/0146167296225009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yu, Z., Wang, F. (2017). Income inequality and happiness: An inverted U-shaped curve. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2052. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liao, T. F. (2021). Income inequality, social comparison, and happiness in the United States. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 7. DOI 10.1177/2378023120985648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22(9), 1095–1100. DOI 10.1177/0956797611417262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bjornskov, C., Dreher, A., Fischer, J. A., Schnellenbach, J., Gehring, K. (2013). Inequality and happiness: When perceived social mobility and economic reality do not match. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 91, 75–92. DOI 10.1016/j.jebo.2013.03.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Alesina, A., di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 2009–2042. DOI 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. He, Q. (2011). Ratchet effect and non-material factors: A normative interpretation of the happiness paradox. The Journal of World Economy, 43(7), 148–160 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

30. Lu, Y. P., Wang, T. (2011). Income inequality, crime and subjective well being: An empirical study from China. China Economic Quarterly, 10(4), 1437–1458 (in Chinese). DOI 10.13821/j.cnki.ceq.2011.04.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Cai, X. Y., Li, X. (2012). China’s public services and population urbanization. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 26(6), 58–65 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

32. Gans, H. J. (1979). Symbolic ethnicity: The future of ethnic groups and cultures in America*. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2(1), 1–20. DOI 10.1080/01419870.1979.9993248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ma, R. (2004). Ethnic sociology–A study of ethnic relations in sociology, pp. 181 (in Chinese). Beijing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

34. Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. DOI 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhou, X. J., Cui, J., Lu, J. (2021). A research on the influence of class positioning and social justice perception on resident’s happiness. Population and Society, 37(2), 94–108 (in Chinese). DOI 10.14132/j.2095-7963.2021.02.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression- based approach (Second edition). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

37. Zhu, Z. K., Leng, C. X. (2017). The living conditions and subjective well-being of migrant workers in Chinese cities: An empirical study based on dynamic monitoring data of floating population. Studies in Labor Economics, 5(2), 56–79 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

38. Liao, L., Wang, C. (2019). Urban amenity and settlement intentions of rural–urban migrants in China. PLoS One, 14(5e0215868. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0215868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhao, X. Y., Gao, Q. K. (2013). Empirical study of public expenditure and public subjective happiness-based on the questionnaire survey in jilin province. Public Finance Research, (6), 13–16 (in Chinese). DOI 10.19477/j.cnki.11-1077/f.2013.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cylus, J., Smith, P. C. (2020). The economy of wellbeing: What is it and what are the implications for health? BMJ, 369, m1874. DOI 10.1136/bmj.m1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lu, H. Y., Yang, L. (2017). Employment quality, social cognition and rural-urban migrants’ sense of happiness. China Rural Survey, 38(3), 57–71 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

42. Rice, T. W., Steele, B. J. (2004). Subjective well-being and culture across time and space. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(6), 633–647. DOI 10.1177/0022022104270107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wang, X., Kong, R. (2014). Income quality and horizontal equity comparison of migrant workers, farmers and urban residents—based on the analysis of migrant workers self-perception. Soft Science, 28(1), 110–114 (in Chinese). DOI 10.13956/j.ss.2014.01.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Lu, H. Y., Zhang, M. (2020). Acculturation strategies, perceived discrimination and the happiness of rural-urban migrants: Evidence from 2395 samples in fujian proince. Journal of Social Development, 7(2), 90–109 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

45. Zhou, X., Chen, S., Chen, L., Li, L. (2021). Social class identity, public service satisfaction, and happiness of residents: The mediating role of social trust. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 659657. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.659657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Soto, C. J., Luhmann, M. (2012). Who can buy happiness? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(1), 46–53. DOI 10.1177/1948550612444139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Li, L. W. (2019). Research progress on the fragmentation of public service supply: Type, cause and crack model. Foreign Theoretical Trends, 27(1), 97–107 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

48. China Labour Bulletin (2021). Migrant workers and their children. China labour bulletin. https://clb.org.hk/content/migrant-workers-and-their-children. [Google Scholar]

49. Florence, É. (2006). Debates and classification struggles regarding the representation of migrants workers. China Perspectives, 2006(3), 1–21. DOI 10.4000/chinaperspectives.629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Jin, X., Ren, T., Mao, N., Chen, L. (2021). To stay or to leave? migrant workers’ decisions during urban village redevelopment in Hangzhou, China. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 782251. DOI 10.3389/fpubh.2021.782251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |