| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.019745

ARTICLE

The Relationship between College Graduate’s Dual Self-Consciousness and Job Search Clarity: The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress

1School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

2College of Education, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

3School of Teacher Education, Yuxi Normal University, Yuxi, 653100, China

4Department of Admissions and Employment Service, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

5Department of Economics, Sheikh Hasina University, Netrokona, 2410, Bangladesh

6Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington DC, 20052, USA

7Department of Psychology, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, 4331, Bangladesh

*Corresponding Author: Yang Li. Email: liyangly@yxnu.edu.cn

Received: 12 October 2021; Accepted: 19 November 2021

Abstract: The aim of the study was to explore the relationship between college graduates’ dual self-consciousness, job search clarity and perceived stress, and reveal the mediating role of perceived stress between dual self-consciousness and job search clarity. In this study, 467 college graduates were investigated using the Dual Self-Consciousness Scale, Job Search Clarity Scale, and Perceived Stress Scale. After controlling for gender, age, and region, the results revealed that: (1) private self-consciousness has a significant positive predictive effect on job search clarity; (2) perceived stress has a significant negative predictive effect on job search clarity; (3) perceived stress plays partial mediation effects between private self-consciousness and job search clarity; (4) perceived stress plays complete mediation effects between public self-consciousness and job search clarity; (5) perceived stress has suppressing effects between public self-consciousness and job search clarity.

Keywords: Private self-consciousness; public self-consciousness; job search clarity; perceived stress; Suppressing effects

With the increasing number of college graduates year by year, employment competition is becoming increasingly fierce. At the same time, due to the superposition of factors such as the downward pressure of the global economy and the transformation and development of China’s industrial structure, it is difficult to change the dilemma of “employment difficulty” of graduates in the future and even for a long period of time [1]. On the other hand, the current situation that many post-90s college graduates “leave” or frequently change jobs after short employment has also become an adverse factor perplexing employers and disturbing the human resources market [2]. The above phenomenon not only reflects that the knowledge and ability structure of college graduates do not adapt to the needs of society and posts, but also reflects the lack of scientific rationality of college graduates’ career positioning, conformity and blindness in career selection, and the lack of clear job search objectives.

Job hunting is a process of goal orientation, motivation and self-regulation [3]; at the core the job search process is one’s goal. This is because goals can transform people’s needs into motivation, provide an incentive effect, point out the direction of efforts and reference standards for individual behavior, and facilitate individuals to adjust and modify their behavior in time, conducive to job success [4]. Clarity is a major attribute of goals. It enables individuals to know more clearly which direction they want to go, how they want to go and how much effort they have to make, which is helps to achieve goals more efficiently [5]. For job seekers, job search clarity refers to the degree to which job seekers have at understanding of the content and type of work they want, the way to get the job they want, and the time it may take to obtain it [6,7]. A more specific definition of job search objectives is helpful for job seekers as it can help to clarify potential obstacles and countermeasures during the job search process. Having clarity and a specific understanding of what one is looking for in a future job can positively impact the intensity, efficiency and results of job search behavior [8–10] as well as create a stronger foundation for individual career development.

The establishment of clear job search objectives needs to be based on the individual’s full self-awareness. The higher the level of self-awareness—the fuller the individual’s understanding of themselves, the external environment (natural and social) they are in, and the relationship between themselves and that environment. This self-awareness can help to deepen one’s understanding of the core issues of career exploration such as what they need, have, and can offer. The more comprehensive this understanding is, the better information provided for career decision-making and the more favorable it is to form clear job search objectives [11–13]. Parsons [14] also believes that self-consciousness is the first and the premise of career exploration and career decision-making. Self-consciousness plays the role of information collection, processing and integration. It is the bridge between individuals and the external environment. It is the necessary basis and core element for college students to form a reasonable self-awareness and clarify their job search objectives. In the process of participating in individual self-cognition, self-consciousness needs to pay attention not only to the interior of self, but also to the external environment. Dual self-consciousness divides self-consciousness into private self-consciousness and public self-consciousness—according to this standard, although separate constructs, they both exist at the same time [15]. Therefore, this study considers private self-consciousness and public self-consciousness as two variables to explore their effects on the clarity of job search goals.

Private self-consciousness refers to the individual’s attention and understanding of their inner selff, such as feelings, attitudes and values [16]. Individuals with a high level of private self-consciousness pay more attention to their internal feelings and needs, and often establish their job search goals according to their own interests, hobbies and needs. Because of this, it can be easier for individuals high on this to define job search goals, as the state of their personal interests are consistent with the type of work they are generally interested in. Public self-consciousness refers to individual’s attention and understanding of external factors such as external evaluation criteria and others’ views on them [17]. Studies have found that individuals with a higher level of public self-consciousness pay more attention to their role as social members, pay attention to the gap between themselves and social standards, and tend to act according to social expectations [18]. Locke et al. [19] point out that external attention to standards can be linked with achievement motivation, and promote people to express themselves in high-level achievement behavior by obtaining external recognition and interests, which may help them establish clear career goals and increase their chances of career success.

For determining clear job search objectives, it is important for individuals to gather sufficient internal and external information about what they want in a career as well as what is needed to obtain that career. Understanding this integration of what goes into this career trajectory, processing that, analyzing what steps are needed to initate and obtain this, and ultimately deciding on what steps to take next are key in determining one’s job search goals and their clarity. At the same time, one’s emotional state can impact the clarity of those goals and the decision-making process [20]. Isbell et al. [21] also pointed out that negative emotions can inhibit the overall processing of information, and that one of the main factors in inducing negative emotions is stress. Specifically perceived stress, which is a series of physical and mental tensions and discomfort individuals feel in stimulating events and threats. Fresh college graduates are not only facing the challenge finding, but are also in a turning point in life, transitioning from school to society. As a result, college graduates often can feel great pressure to find a job upon or before graduating. We anticipate that the resulting negative emotional problems for trying to find employment can affect graduates’ mental health and jointly affect the clarity of their job search objectives. Perceived stress is likely to be an intermediary factor between dual self-consciousness and job search clarity. In this study, five hypotheses were tested:

H1—Private self-consciousness positively predicts job search clarity;

H2—Public self-consciousness positively predicts job search clarity;

H3—Perceived stress negatively predicts job search clarity;

H4—Perceived stress plays a mediating role between private self-consciousness and job search clarity;

H5—Perceived stress plays an intermediary role between public self-consciousness and job search clarity.

A total of 500 questionnaires were distributed to individuals who just graduated from college and who in the fourth year of undergraduate had only a job search plan. The individuals who reported having other choices such as postgraduate entrance examination, entrepreneurship and freelance were deleted. A total of 467 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective recovery rate of 93.4%. Participants’ ages ranged between 21 and 25 years (M = 22.1; SD = 0.7). Among them 253 (54.2%) were women and 214 (45.8%) were men; 156 (33.4%) were from the urban areas and 311 (66.6%) rural areas. Other demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1.

2.2.1 Dual Self-Consciousness Scale

The Chinese version [22] of the Self-Consciousness Scale [23] was utilized to assess Dual Self-Consciousness. There are 17 items in the scale, of which 10 items measured private self-consciousness (including “I usually pay close attention to my inner feelings”); 7 items measured public self-consciousness (including “I care about what others think of me”). The measure was scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The higher the total score of the public self-awareness subscale, the higher the level of public self-awareness, and the higher the total score of the private self-awareness subscale, the higher the level of private self-awareness. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of total scale is 0.838, The Cronbach’s α of public self-awareness and private self-awareness scale are 0.802 and 0.760, respectively.

The Chinese version [24] of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) [25] was utilized to assess perceived stress. There are 10 questions in the scale, including two dimensions of crisis perception and coping style. The scale includes four reverse scoring questions, which are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The higher the total score of all items, the higher the subjects’ stress perception. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of total scale is 0.800.

2.2.3 Job Search Clarity Scale

Job search clarity was assessed using the subscale of it from the Job Search Self-Efficacy Questionnaire [26]. The questionnaire contains 7 questions, which are scored from 1 to 5; each question is then summed for a score of one’s job search goal clarity. The higher the score, the clearer the job search goal. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of total scale is 0.920.

In this study, SPSS 25.0 version was used for statistical analysis of the data, Mplus 8.0 was used for structural equation model construction analysis, and the mediation effect test was conducted by constructing 5,000 random samples with return and estimating the 95% confidence interval.

The present study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The Ethics Committee of the Northwest Normal University, China approved this study (ERB No. 2021016, Dated: 9/3/2021).

This study controls for common method deviation by setting some items as reverse questions during sample collection and measurement. In addition, the Harman single factor test was used to test the common method deviation of the collected data. The results of non-rotating exploratory factor analysis extracted 6 factors with characteristic roots greater than 1, of which the interpretation rate of the maximum factor variance was 23.55%, less than the critical value of 40%, which shows there is no serious common method deviation in this study.

3.2 Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Compared with previous studies, the average value of the total score of self-awareness of college graduates in this study is significantly lower than the research results of Chen et al. [27] (t = −3.078, p < 0.001); there was no significant difference between the average value of the total score of public self-awareness and this study (t = −1.481, p > 0.05). The average of the total score of stress perception was significantly higher than that of Qin et al. [28] (t = 4.260, p < 0.001). The average value of the total score of job search clarity is significantly lower than the research results of Kang et al. [29] (t = −6.156, p < 0.001). This shows that college students in the job-searching period have an insufficient understanding of themselves, unclear job-searching objectives and are under greater stress. As shown in Table 2, there is a significant positive correlation between private self-consciousness and public self-consciousness, and both are significantly positively correlated with the clarity of job search objectives. Perceived stress is significantly negatively correlated with private self-consciousness, positively correlated with public private self-consciousness, and negatively correlated with job search clarity.

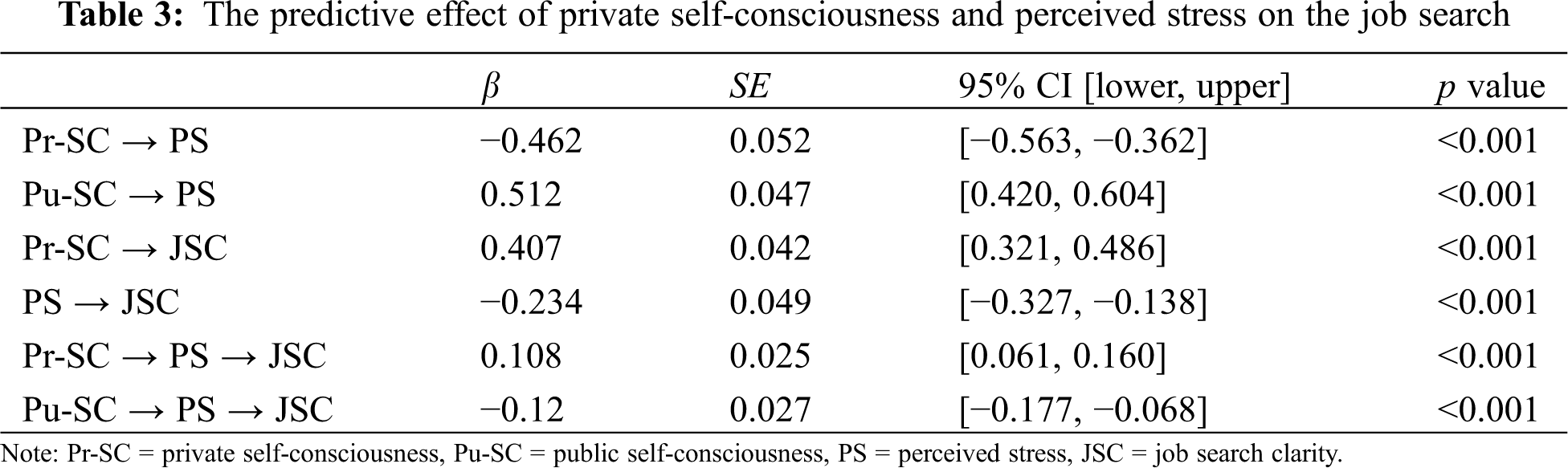

3.3 The Predictive Effect of Dual Self-Consciousness and Perceived Stress on Job Search Clarity

Multiple stepwise regression analyses were carried out with private self-consciousness, public self-consciousness and perceived stress as predictive variables and job search clarity as the outcome variable. The results are shown in Table 3. The variables that can significantly predict the job search clarity are private self-consciousness and perceived stress, which explains 25.7% of the variation for job search clarity.

3.4 The Predictive Effect of Dual Self-Consciousness and Perceived Stress on Job Search Clarity

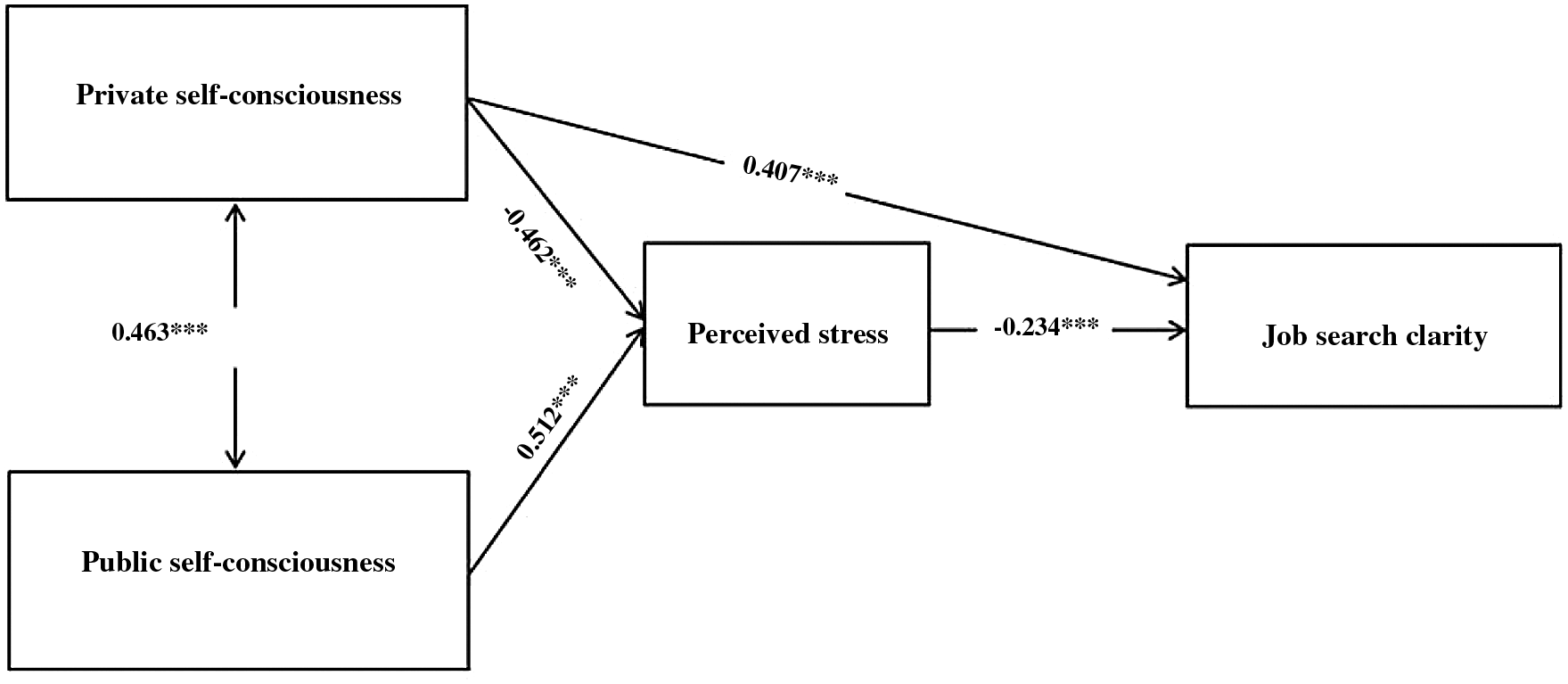

On the basis of the correlation analysis, we used Mplus 8.0 further to construct and analyze the structural equation model, and test the mediating role of perceived stress between dual self-consciousness and job search clarity. Taking private self-consciousness and public self-consciousness as predictive variables; gender, age and region as control variables; and job search clarity as the outcome variable, four paths were constructed: private self-consciousness → perceived stress → job search clarity; public self-consciousness → perceived stress → job search clarity; private self-consciousness → job search clarity; and public self-consciousness → job search clarity. The boot-strap method was used to test the mediating effect directly through 5,000 repeated sampling. The results show that the fitting degree of the model is poor. According to the hint of the model correction index, after deleting the direct path of public self-consciousness → job search clarity, the verification results of the modified model show that the fitting degree of the model is good (χ2 = 294.814, df = 11, χ2/df = 3.372, RMSEA = 0.071, CFI = 0.992, TLI = 0.908, SRMR = 0.015). In order to better show the mediation effect model, the path from the control variable to the dependent variable is not presented. The simplified modified model is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Simplified modified model

The path analysis results of the structural equation model showed that: the direct effect of private self-consciousness → job search clarity was significant (p < 0.001), the effect value was 0.407, and the 95% confidence interval was [0.321, 0.486]; the indirect effect of private self-consciousness → perceived stress → job search clarity path is significant (p < 0.001), the effect value is 0.108, and the 95% confidence interval is [0.061, 0.160]. This indicates that perceived stress has a significant partial mediating effect between private self-consciousness and job search clarity. The indirect effect of public self-consciousness → perceived stress → job search clarity is also significant (p < 0.001), the effect value is −0.120 and the 95% confidence interval is [−0.177, −0.068]. This indicates that the mediating effect of perceived stress between public self-consciousness and job search clarity is significant and plays a complete mediating role. On the other hand, the intermediate effect value ab is opposite to the sign of c and c′, indicating that there is a “suppressing effect” that is the phenomenon that the indirect effect in the intermediary effect offsets the direct effect, resulting in a low or even non-significant total effect [30].

For college graduates, active and effective job-searching behavior (maintaining appropriate frequency and intensity of job-searching behavior, degree of job-hunting effort, and rational use of job-searching resources) is a necessary condition for their successful employment [31–33]. Some studies have found that individuals with higher job search clarity have more active and effective job-hunting behavior [34,35]. Therefore, job search clarity is the key to success in getting a job for college graduates. This study reveals the mediating effect of perceived stress on dual self-consciousness and job search clarity by exploring this relationship among college graduates.

4.1 Relationship between Private Self-Consciousness, Public Self-Consciousness and Job Search Clarity

The results show that there is a significant positive correlation between one’s own self-awareness and job search clarity, and this self-awareness can positively predict job search clarity, which supports H1. In real life, people with a high level of private self-consciousness pay more attention to their interests and hobbies. People are usually willing to spend more time on their favorite activities, which can help them to think deeply about the specific contents of career goals and clarify the methods to achieve them. The results also revealed a significant positive correlation between public self-consciousness and job search clarity. This may be because job seekers who pursue external evaluation often actively pay attention to the development of social situations and the needs of the employment market, which is conducive to individuals to effectively use this information to establish their job search goals. Moreover, a strong sense of social responsibility and professional mission are also important ways to improve job search clarity [36]. However, public self-consciousness was not found to predict the job search clarity, so we fail to reject H2. This may be because individuals with a high level of public self-consciousness often neglect their own needs due to an excessive pursuit of social recognition when making career choices [37].

From the micro level, everyone can get the career they are interested in and good at, which is the favorable basis for an individual’s career development. From a macro perspective, helping individuals make career choices consistent with organizational and social needs is also a necessary measure to promote social development and progress [38]. Therefore, under the comprehensive consideration of social development and personal development, in order to improve the job search clarity of college students, it is necessary to make a reasonable analysis of students’ private self-consciousness and public self-consciousness, and promote their harmonious development on this basis.

4.2 Relationship between Perceived Stress and Job Search Clarity

The results show that perceived stress negatively predicts job search clarity, supporting H3. This is because, when individuals perceive greater perceived stress (such as difficulty to overcome an obstacle, lack of necessary support, etc.), they often do not turn their interest into career goals, and it is difficult to trigger effective actions [39,40]; furthermore high stress is not conducive for individuals’ to make better decisions [41]. For the vast majority of fresh graduates, job hunting is a major challenge in life, and it is inevitable to feel the pressure finding and getting a job. Tension, anxiety and other negative emotions caused by stress are important factors leading to their career decision-making difficulties, which can cloud the formation of clear job search goals [42,43].

Therefore, the employment services of colleges and universities can take the adjustment of graduates’ stress perception into consideration. Specifically, they can start by understanding their levels of stress on the student level and from society more broadly. They can also provide support and guide graduates to correctly understand the possible setbacks, learn positive stress coping styles [44], master the methods of emotion regulation, and help them manage their time more efficiently to alleviate their stress perceptions [45,46]. Further, uniting families and society to provide practical employment support for graduates and build a positive and safe job-hunting atmosphere (for example, avoid blindly exaggerating the degree of employment difficulties) should also be considered in order to lessen stress levels. Other studies have shown that clear goals can in turn alleviate job seekers’ anxiety and stress [47,48]. By providing support and lessening anxiety, job-hunting for graduates can become more clearer.

4.3 The Role of Perceived Stress between Dual Self-Consciousness and Job Search Clarity

The model constructed in this study shows that perceived stress plays a partial intermediary role between private self-consciousness and job search clarity, supporting H4. Additionally, perceived stress plays a complete mediating role between public self-consciousness and job search clarity, which supports H5. Moreover, there is a special case found in this study where perceived stress has a “suppressing effect,” in the relationship between public self-consciousness and job search clarity, resulting in the failure of the direct path from public self-consciousness to job search clarity. This effect explains the low correlation between public self-consciousness and job search clarity in this study. That is, perceived stress masks the relationship between public self-consciousness and job search clarity, reducing the correlation between them. This is also one of the reasons for the low correlation between public self-consciousness and the job search clarity than for job search clarity and private self-consciousness, in this study. The model constructed also shows that for the path public self-consciousness → perceived stress → job search clarity, the higher the public self-consciousness, the higher the perceived stress, which inhibits the improvement of job search clarity; indicating that pressure perception is an obstacle between public self-consciousness and job search clarity. For senior graduates, the employment problem is imminent. They do not have much time for career exploration. This time pressure can affect the depth and mode of career information searches, which can reduce the quality of career decision-making [49] and lower the clarity and rationality of their job search objectives. However, in the path of private self-consciousness → perceived stress → job search clarity, the higher the private self-consciousness, the smaller the perceived stress, which promotes the improvement of job search clarity, indicating that perceived stress is a favorable factor between private self-consciousness and job search clarity. Individuals with a high level of private self-consciousness need to appropriately increase crisis awareness, which is conducive to making decisions faster and clarifying job search objectives. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the characteristics of dual self-consciousness when adjusting for stress perception to help graduates clarify their job-hunting goals.

5 Limitations and Future Research

The present study has some limitations. First, the research participants recruited in this study are college students in Northwest China. Compared with other regions in China, the economy of this region is not as developed, and the employment market is not very prosperous, which can have narrowing impacts in terms of their vision and horizons for understanding the vast amount of available employment options. Therefore, whether the results of this study are applicable to college students in other parts of China remains to be discussed and further investigation. Second, this study only uses scale tools to collect data, and the research method occurred at one timepoint; the data also could be biased based on the deterioration of the social approval expectation or memory of the participants. Third, there might be other factors that contribute to job search clarity for Chinese graduates not assessed in this study. In this study, we only examined the contribution of perceived stress and dual consciousness to job search clarity.

Further research should include representative samples from different regions of China in order to obtain an overall norm, providing a more general basis for this evaluation. In addition, future research can also adopt the mixed research paradigm combining qualitative research and quantitative research, and combine experimental research methods more deeply. Finally, the level of dual self-consciousness and perceived stress is not invariable, and the career guidance (assessment and intervention) carried out by colleges and universities for college students also needs to be tracked for across time to achieve better results.

Results of this study show that dual self-consciousness ultimately affects college graduates’ job search clarity through perceived stress. For them, perceived stress is not only a favorable factor between private self-consciousness and job search clarity, but also a hindering factor between public self-consciousness and job search clarity. In view of the complex role of perceived stress, we should guide college students reasonably on the basis of clarifying their level of private self-consciousness and public self-consciousness which can help adjust their perceived stress and overall help to improve their job search clarity.

This study further enriches the theory of career development and provides empirical evidence for the direction of career planning intervention for college students. It also has important educational significance for improving job search clarity of college students. In summary, college students need to start career planning as early as possible; invest more time in career exploration; reasonably improve their level of private self-consciousness and public self-consciousness; have a better handling on stress so that it does not interfere; and put forth efforts to initate improving their job search clarity—so they can lay the foundation for high-quality successful employment and rapid development of career. A start to helping recent graduates can be for the career planning services offices and programs in universities to take these variables into consideration and create resources to better serve undergraduates and recent graduates at whatever stage they are in to propel them to their desired career trajectory.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the respondents for their time to complete the survey.

Data Availability Statement: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the academic requirements for the National Education Science Planning Project of China under Grant No. BBA210041.

Conflicts of Interest: This study was carried in the absence of any personal, professional, or financial relationships that could potentially be constructed as a conflict of interest.

1. Zhou, M., Lin, J. (2015). Chinese graduates’ employment: The impact of the financial crisis. International Higher Education, 3–4. DOI 10.6017/ihe.2009.55.8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yu, X. L. (2019). Why college graduates prefer job hopping. People’s Tribune, (2), 110–111. [Google Scholar]

3. van Hooft, E. A. J., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Wanberg, C. R., Kanfer, R., Basbug, G. (2021). Job search and employment success: A quantitative review and future research agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(5), 674–713. DOI 10.1037/apl0000675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Locke, E. A., Latham, G. P. (1990). Work motivation and satisfaction: Light at the end of the tunnel. Psychological Science, 1(4), 240–246. DOI 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00207.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang, M. L., Che, H. S. (1999). Goal setting theory and its new development. Advances in Psychological Science, 7(2), 35–40+34. [Google Scholar]

6. Wanberg, C. R., Hough, L. M., Song, Z. (2002). Predictive validity of a multidisciplinary model of reemployment success. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1100–1120. DOI 10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Côté, S., Saks, A. M., Zikic, J. (2006). Trait affect and job search outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 233–252. DOI 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Guo, Y., Chen, J. Q., Wang, L. (2005). Occupational clarity: Concepts, survey analysis and applications. Human Resources Development of China, (2), 22–25. DOI 10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2005.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zikic, J., Saks, A. M. (2009). Job search and social cognitive theory: The role of career-relevant activities. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(1), 117–127. DOI 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bao, Z., Luo, P. (2015). How college students’ job search self-efficacy and clarity affect job search activities. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 43(1), 39–52. DOI 10.2224/sbp.2015.43.1.39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kang, T. H., Wang, P. (2011). The effects of valence matching of different information on decision-makers’ occupational option behavior. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 9(4), 247–250. [Google Scholar]

12. Lee, B., Porfeli, E. J., Hirschi, A. (2016). Between-and within-person level motivational precursors associated with career exploration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92(2), 125–134. DOI 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhu, H., Zhang, H., Tu, A., Zhang, S. (2021). The mediating roles of core self-evaluation and career exploration in the association between proactive personality and job search clarity. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 609050. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.609050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Boston, MA, USA: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. [Google Scholar]

15. Hamid, P. N., Lai, J. C. L., Cheng, S. (2001). Response bias and public and private self-consciousness in Chinese. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 29(8), 733–742. DOI 10.2224/sbp.2001.29.8.733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. F., Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43(4), 522–527. DOI 10.1037/h0076760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. DaSilveira, A., DeSouza, M. L., Gomes, W. B. (2015). Self-consciousness concept and assessment in self-report measures. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 930. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Green, J. D., Sedikides, C., Saltzberg, J. A., Wood, J. V., Forzano, L. B. (2003). Happy mood decreases self-focused attention. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(1), 147–157. DOI 10.1348/014466603763276171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Locke, E. A., Schattke, K. (2019). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Time for expansion and clarification. Motivation Science, 5(4), 277–290. DOI 10.1037/mot0000116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Stavraki, M., Lamprinakos, G., Briñol, P., Petty, R. E., Karantinou, K. et al. (2021). The influence of emotions on information processing and persuasion: A differential appraisals perspective. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 93(4), 16. DOI 10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Isbell, L. M., Rovenpor, D. R., Lair, E. C. (2016). The impact of negative emotions on self-concept abstraction depends on accessible information processing styles. Emotion, 16(7), 1040–1049. DOI 10.1037/emo0000193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jiang, C. (2007). A revision of the self-consciousness scale and it’s correlative research. (Master’s Thesis). https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD2007&filename=2007131404.nh. [Google Scholar]

23. Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S. (1985). The self-consciousness scale: A revised version for use with general populations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 15(8), 687–699. DOI 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1985.tb02268.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu, W. T., Yi, J. Y., Zhong, T. M., Zhu, X. Z. (2015). Measurement invariance of the perceived stress scale in college men and women. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 944–946. [Google Scholar]

25. Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. DOI 10.2307/2136404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hu, Y. H., Liu, X. (2006). A comparison of undergraduate’s occupational choice self-efficacy. Journal of China Women’s University, 18(2), 22–27. DOI 10.13277/j.cnki.jcwu.2006.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chen, J. F., Wei, J., Zhang, J. F., Lu, S. (2014). Moderating role of self-focused attention on the relationship between stress and negative affect. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 22(6), 1087–1090+1086. DOI 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2014.06.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Qin, P. F., Zhao, S. Y., Li, D. L., Huang, M. M., Liu, G. Q. (2020). The effect of perceived stress on college students’ mobile phone addiction: A serial mediation effect of self-control and learning burnout. Journal of Psychological Science, 43(5), 1111–1116. DOI 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kang, T. H., Wang, X. Z. (2008). College students’ value orientation of career choice and job-seeking self-efficacy. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 22(7), 475–479. [Google Scholar]

30. Wen, Z. L., Ye, B. J. (2014). Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Advances in Psychological Science, 22(5), 731–745. DOI 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.00731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang, T. S., Lu, X. H., Fang, F. M. (2012). An empirical study on self-efficacy, objective clarity and resource mobilizing behavior in college student’s job hunting. Journal of Beijing Jiaotong University (Social Sciences Edition), 11(1), 68–72. DOI 10.16797/j.cnki.11-5224/c.2012.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xie, Z. Y., Lu, H. L. (2016). A longitudinal study of the effects of employability and job search behaviors on job search outcomes of college graduates. Management Review, 28(1), 109–120. DOI 10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2016.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Saks, A. M., Ashforth, B. E. (2002). Is job search related to employment quality? It all depends on the fit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 646–654. DOI 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Feng, C. L. (2016). A longitudinal study on influences of job-search clarity on career development: Based on social cognitive career theory. Journal of Shandong Normal University (Social Sciences), 61(2), 121–127. DOI 10.16456/j.cnki.1001-5973.2016.02.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wang, W., Dai, L. (2017). A review of researches on job search clarity. Psychology, 8(7), 955–962. DOI 10.4236/psych.2017.87062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Shen, X. P., Hu, S. (2015). Relationship between proactive personality and job search clarity of undergraduate students: Calling as a mediator and moderator. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23(1), 166–170. DOI 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2015.01.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wanberg, C. R., Muchinsky, P. M. (1992). A typology of career decision status: Validity extension of the vocational decision status model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 39(1), 71–80. DOI 10.1037/0022-0167.39.1.71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Dobrow Riza, S. D., Heller, D. (2015). Follow your heart or your head? A longitudinal study of the facilitating role of calling and ability in the pursuit of a challenging career. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 695–712. DOI 10.1037/a0038011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 36–49. DOI 10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Bhui, K., Dinos, S., Galant-Miecznikowska, M., de Jongh, B., Stansfeld, S. (2016). Perceptions of work stress causes and effective interventions in employees working in public, private and non-governmental organisations: A qualitative study. BJPsych Bulletin, 40(6), 318–325. DOI 10.1192/pb.bp.115.050823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Gray, J. R. (1999). A bias toward short-term thinking in threat-related negative emotional states. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(1), 65–75. DOI 10.1177/0146167299025001006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Yao, Q., Li, H., Huang, W. M. (2012). Analysis of college students’ career decision-making self-efficacy and their employment pressure. Journal of College Advisor, 4(1), 52–55. DOI 10.13585/j.cnki.gxfdyxk.2012.01.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wu, G., Hu, Z., Zheng, J. (2019). Role stress, job burnout, and job performance in construction project managers: The moderating role of career calling. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2394. DOI 10.3390/ijerph16132394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Masiran, R., Ismail, S. I. F., Ibrahim, N., Tan, K., Andrew, B. N. et al. (2021). Associations between coping styles and psychological stress among medical students at Universiti Putra Malaysia. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 40(3), 1257–1261. DOI 10.1007/s12144-018-0049-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Balk Y. A., Adriaanse M. A., de Ridder D. T. D., Evers C. (2013). Coping under pressure: Employing emotion regulation strategies to enhance performance under pressure. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 35(4), 408–418. DOI 10.1123/jsep.35.4.408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhang, F., Liu, J., An, M., Gu, H. (2020). The effect of time management training on time management and anxiety among nursing undergraduates. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 26(9), 1–6. DOI 10.1080/13548506.2020.1778751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Veiga, S. P. D. M., Turban, D. B. (2014). Are affect and perceived stress detrimental or beneficial to job seekers? The role of learning goal orientation in job search self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 125(2), 193–203. DOI 10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.09.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ozbay, F., Johnson, D. C., Dimoulas, E., Morgan, C. A.III, Charney, D. et al. (2007). Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry, 4(5), 35–40. [Google Scholar]

49. Chen, J. (2009). The influence of attributional style and time pressure on information processing in decision making. Journal of Psychological Science, 32(6), 1445–1447. DOI 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2009.06.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |