| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.015169

ARTICLE

Effect of Social Media Celebrities on Children’s Satisfaction with Their Body Image

Early Childhood Department, College of Education, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11362, Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding Author: Raja Omar Bahatheg. Email: rbahatheg@ksu.edu.sa

Received: 26 December 2020; Accepted: 26 May 2021

Abstract: This study investigated the impact of social media and media on children’s body satisfaction in early childhood. The effect of social media and media on children’s body image and differences between girls’ and boys’ acceptance of their body image were explored. A questionnaire and an illustrated body satisfaction scale were distributed to a sample of 491 children in Saudi Arabia (246 girls, 245 boys) aged 5–7 years. The results revealed differences between children’s responses to the illustrated body satisfaction scale and questionnaire. Questionnaire data revealed children were satisfied with their body image (91.4%, standard deviation [SD] 0.53), skin color (91.2%, SD 0.53), and weight (79.6%) and did not want to change their shape (73.7%). However, the illustrated body satisfaction scale indicated many children wanted to be like social media celebrities (37.9%), television and film celebrities (32.6%), and famous singers (25.5%). No statistically significant differences were found between girls and boys in body satisfaction, although 66.9% of boys wanted the shape of their body to be more muscular, and girls wanted blue or green eyes and blond hair. This study also revealed Disney princesses had a major effect on girls compared with other media. The researcher recommends conducting longitudinal studies in Arab societies, particularly in Saudi Arabia, to explore the influence of celebrities on children as they age. Importantly, educational policymakers should include pictures of Arab children in the curricula instead of foreign children.

Keywords: Body image; social media; body satisfaction; pre-school; children

Children’s body image is a crucial topic in educational and psychological research as it has a positive or negative effect on their self-image and mental health. Despite existing research on this topic, more research is needed because emerging national and international changes in different aspects of life may affect children’s thinking and mental health. Conducting research in the Arab world, particularly in Saudi Arabia, is also important because of the paucity of studies in this area and the impact of various national and international changes on children’s lives. This study aimed to investigate the effects of social media and media on Saudi children’s body satisfaction in early childhood. To achieve this objective, this study drew on relevant conceptual and empirical literature to construct the theoretical framework for the investigation.

As children develop, they begin to recognize differences in their bodies and construct social judgments about people based on their body image. This process starts with the child identifying an image of the “ideal” body, and consequently trying to achieve this ideal. Children may develop a positive attitude toward this image of the ideal body while forming a negative attitude toward an image of the overweight body, which impacts and weakens their social relationships with others [1]. Researchers have also observed that at the pre-school stage, children of both sexes are already familiar with their culture’s body image stereotypes [2,3] for example, 3-year-old American and Australian boys and girls preferred thin- to medium-sized bodies and rejected overweight children [4]. These stereotypes of obesity and thinness affect young children and are enhanced through social media.

The concept of “body image” was introduced as a psychological phenomenon in 1935 [5], which suggested that the mental image we have of our bodies explains the way our body is presented to ourselves. Some cholars [6] expanded this concept by defining body image as the mental image of our body characteristics (e.g., size, shape, and circumference), and noted our feelings are related to these characteristics and to our body parts. The concept of “satisfaction/dissatisfaction” in relation to body image emerged later and was defined as an individual’s feelings and behavior toward their own body. Grogan et al. [7] described body dissatisfaction as “the negative thoughts of his/her body” (p. 4), including unsatisfactory judgments about size, shape, and muscle tone and generally involving a discrepancy between one’s own and one’s ideal body type [8]. Burrowes [9] stressed that theterm “body image” incorporates body perception (extent to which an individual has an accurate perception of their body size, shape, and weight) and body satisfaction (extent to which an individual is satisfied with these body aspects).

Most research on “body image” has focused on the following two topics:

1. Body perception: This refers to an individual’s evaluation of the physical aspects of their bodies and the accuracy of this evaluation. In severe cases, individuals may suffer from body dysmorphic disorder, which is a psychological disorder in which individuals have inaccurate perceptions of their body size. Cash et al. [10] added one’s body-related self-perceptions and self-attitudes, including thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors.

2. Body satisfaction: This refers to the extent to which an individual assesses the size and shape of their body, including their ideas of body confidence, respect for the body, and body dissatisfaction.

Behavioral and social learning theories stress the importance of the environment and care in child development, including Watson [11], who stated that children are human beings that can be shaped like clay. Skinner’s theory of conditioning [12] introduced the term “operant conditioning” to describe how learning occurs as a result of human beings’ response to their environment. Social learning theory [13] notes that children learn by observation and imitation, tend to be selective in what they imitate, and are keen to imitate behavior patterns that satisfy them. Various cognitive development theories have examined how children learn. Pigat [14] focused on the individuality of the child, what children really know, and how they construct knowledge. Children’s understanding of the world is the result of their involvement and interaction [15], as well as the individual cognitive experiences of others around them. In his sociocultural theory, Vygotsky et al. [16] stressed that children’s knowledge is socially constructed and children adopt the values, beliefs, and problem-solving strategies of their culture as a response to social interaction with the most knowledgeable members of their community.

In reviewing the development of cognitive theory in children, Kohlberg et al. [17] stated that at a young age, children can classify themselves as male or female and recognize their own physical development as they begin to realize their body’s physical growth, and start comparing their bodies to those of other children around them. Bandura’s social cognitive theory, Bandura et al. [13], states that, “in the course of development, the regulation of behavior shifts from predominantly external sanctions and mandates to gradual substitution of self-sanctions and self-direction grounded in personal standards” (Albert Bandura | Social Learning Theory | Simply Psychology, n.d.).This emphasis on personal standards posits a greater involvement of the child’s self-concept in evaluative self-reactions as a key developmental shift. Cognitive theory researchers have observed how some individuals do not like certain aspects of their bodies and as a result of these feelings, may develop a disorder that usually appears in adulthood [18,19]. Individuals also tend to compare themselves with others in an attempt to self-assess their appearance [20]. They tend to make these comparisons with those similar to them; for example, comparing their body image with an “ideal” individual’s body that is similar in shape or making negative comparisons with an individual’s body that is far from being their ideal body [21,22]. Body image is a kind of perception that includes both evaluative and cognitive components [23]. The thin body ideal appears to be an important personal standard for young girls that becomes internalized as part of their developing self-concept, and draws a parallel between overt behavior and children’s thoughts and feelings regarding their bodies [24].

The media plays an educational role in providing messages to viewers about the dangers of disordered eating behaviors [25] and poor nutrition [26]. It is also used educationally to inform girls and young women about specific health issues related to their weight and appearance. However, the media can play a negative role in body image depictions by increasing girls’ and boys’ anxiety about their appearance [27]. For example, the stereotype of physical attractiveness can cause some people to believe that attractive people are more happy and popular [28]. This stereotype is often seen in film characters and commercial advertisements [29]. In addition, personal attractiveness is often perceived as closely related to good morals, a better standard of living, and low levels of aggression in both males and females [30].

Imagination and play constitute an essential part of young children’s socialization in which they learn ideals and values. Toys provide children with a concrete image of the body that can be understood as part of their developing body [31]. Moreover, according to sociocultural theory [32], body image issues are at the core of major eating disorders, but are also important phenomena in and of themselves. Thompson and colleagues provided an overview of a variety of body image issues, ranging from reconstructive surgery to eating disorders [33]. Media and toys are powerful ways to enhance body image and satisfaction [34]. For example, the ideal of “beauty” for girls is present in many aspects of their socio-cultural environment (e.g., advertising, television, and peer groups). Toys are another form of media that impact children; for example, Barbie dolls are so thin that their weight is not only unlikely but also unhealthy. The ideal of adult feminine beauty presented in this toy has been linked to negative body image and unhealthy eating patterns among girls and women. Dittmar et al. [24] compared the impact of Barbie dolls with that of the “Emme” dolls, which are based on a real-life, size 16 (American size) model. The study concluded that Barbie dolls negatively impacted girls aged 5–8 years by decreasing body image esteem and increasing the desire to be thin. The same impact was recently confirmed by Nesbitt et al. [35]. Other researchers have also expressed concerns about the impact of Disney princesses on young girls and boys [36], although little empirical research has examined the impact of Disney princesses—as portrayed in the media—on preschoolers’ behavior, gender stereotyping, body image esteem, and positive social behavior.

Previous Studies

Several studies have focused on body image from different perspectives (e.g., gender differences, ages, social media). This section intends to provide an account of studies that are relevant to the present research. Burrowes found that that gender was the main factor in establishing who is most impacted by negative body image, with females more likely to have lower body satisfaction than males regardless of age or ethnicity. Esnaola et al. [37] also noted that girls cared more than boys about having a “perfect” body. It has been observed that young children are more likely to be bullied about their body image than older counterparts, and adolescent girls are more likely to be bullied for their physical appearance than boys; however, it is not clear to what extent this bullying is affected by appearance [38,39]. Furthermore, girls tend to try to lose weight, whereas males attempt to increase muscle size [40]. da et al. [41] raised an important point about gender, suggesting that very thin males were less satisfied with their bodies than very thin females. Rasmussen et al. [42] maintained that there was a difference in the way boys and girls answered questions regarding their bodies; boys were more honest about their body weight, whereas girls reported being lighter than the reality. However, Wardle et al. [43] stated that overweight boys did not report that they were overweight or trying to lose weight.

Gender differences in body image appear between the ages of 8 and 10 years as children are influenced by their companions [44,45]. Girls tend to have a thinner body image than their actual bodies, and boys have similar concerns about their body image and want to avoid becoming overweight [46]. Young girls’ body image satisfaction and the desire to be thinner increases with age; 40% of girls aged 8–9 years wanted to be thin, which increased to 79% of girls aged 11–12 years [47]. A study conducted with girls aged 5–8 years concluded that their desire for thinness appeared at age 6 years [48]. However, Dittmar et al. [24] observed that even at age 5 years, girls wanted to have a slim body.

Some studies demonstrated that preschool children adopted body image stereotypes; however, these studies provided no evidence of whether children of this age adopted these views on their own. It has also been reported that it is difficult to study personal internalization of these opinions in children under 6 years; most previous research asked children to decide on the body shape they preferred, or decide which body shape was similar to theirs (for example, “attractive/ugly”) in books that were read to them. However, preschool children cannot accurately determine the shapes that represent their body type or their feelings about their body image [49,50].

Few studies have addressed body image, weight, and self-concept among girls aged 5–7 years [51]. One study found that weight gain was associated with lower body image esteem and more negative self-understanding, that children aged 6 and 13 years showed evidence of body dissatisfaction, and that children of all age groups showed a desire to be thinner [52]. However, other research revealed that 4- to 6-year-olds preferred thin body types [4]. Children aged 4–5 years were likely to avoid obese peers (although this was not the case for 3-year-olds) because they perceived that thinness was associated with popularity and not teasing each other [53]. Further studies revealed that children’s non-acceptance of their bodies leads to low self-esteem [54]. However, although the theme of body image satisfaction has often been examined among older adolescents and young adults, limited studies have examined this topic among children [55,56]. The abovementioned studies recommended more extensive research on this topic to bridge this knowledge gap; therefore, the present study focused on the impact of different media types on children’s body image satisfaction in early childhood.

The literature examining the body image presented by Disney princesses observed that the typical princess is a young and attractive woman with large eyes, a small nose and chin, prominent cheekbones, shiny hair, and good skin. The princesses’ bodies also represent the “ideal” slimness; that is, an imaginary feminine, thin figure. Research has also revealed that in the pre-school stage, 5-year-olds showed interest in thin body types, and girls of this age voiced concerns about becoming overweight and started to exhibit body dissatisfaction and low self-esteem [57,58]. It has also been suggested that Disney princess films may be an early context that teaches girls that attractiveness is an essential component of female identity [36].

Media messages about the ideal, slim body are powerful, widespread, and may negatively affect viewers’ body esteem [36,59]. Although most research has examined the impact of media on girls and older women, longitudinal studies have indicated that girls’ early exposure to the ideal slim body in the media predicts negative future impacts, including low self-esteem and irregular eating behaviors [60,61]. Furthermore, exposure to ideally slim toys (e.g., Barbie) also results in low body image esteem for younger girls; therefore, Disney princess films and their associated advertisements are of concern because they may represent part of children’s initial media exposure to the thin/slim body ideal [62].

To our knowledge, few studies have investigated children’s exposure to Disney princesses and its impact on their body image esteem in the Arab world, particularly in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In their semi-empirical study, Hayes et al. [63] presented a series of appearance-related clips, including several Disney film clips (e.g., Cinderella and the Little Mermaid). They concluded that girls in the control group who were not exposed to these clips did not experience body dissatisfaction or appearance-related behaviors (for example playing dress-up more often, playing with a vanity). However, that study indicated the impact of short-term exposure to the media of the ideal slim body may not be particularly strong for young girls, but this exposure may subsequently influence their body image esteem. Moreover, that study concluded that although boys were not affected by the idea of slimness, they were affected by the images of bodies with large muscles and thin waists.

Cm et al. [64] examined and analyzed 7,681 research papers that addressed the issues of body satisfaction and image to review the extent of concerns about the impact of media and thinness on young children’s health, psychological states, weight, and body shape. They found that the analyzed studies showed that most children were dissatisfied with their body image; however, most studies used quantitative (87.9%) or cross-sectional (78.8%) designs, confirming a scarcity of qualitative and longitudinal research results. Image scales represented 60.6% of the research tools used in these studies, and several studies (33.3%) proposed evaluating more than one dimension of body image; in particular, “body perception and body dissatisfaction”. Some studies also evaluated “other detentions related to body image”, such as children’s understanding of body shape and their comprehension of the ideal thin body type (18.2%). According to the body image dimensions they addressed, the results of these studies were discussed and categorized into three topics: “body dissatisfaction in children”, “body perception in children” and “other elements related to the body image. Wedwick et al. [65] also analyzed 71 books about children and childhood stages. They found 3,345 images, of which 3,260 represented children who were not obese and 85 images depicted children who were obese (i.e., only 3% of the books included obese characters). This may lead to children’s dissatisfaction with their own body image [66].

Social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter, Tik Tok, YouTube, and Instagram affect children and adolescents and impact how they view themselves and their body image. Teenagers share immediate and effective comments among each other regarding appearance and self-expression. Moreover, social media opens up the world to children and helps them to communicate with their friends globally [66]. Tiggemann et al. [67] examined the relationship between Internet exposure and body image concern in adolescent girls, revealing that websites influenced girls’ interest in being slim and increased their participation in the monitoring of body weight. Research has also revealed that exposure to ideal body images can lead to a mild to moderate decrease in body satisfaction and perception [68]. In addition, pre-existing lower body satisfaction appears to affect such outcomes, as individuals who already had low body satisfaction were likely to be negatively affected by images of ideal body types, whereas individuals with high body satisfaction were not [69–72].

Children have cognitive mechanisms that allow them to be less affected by advertising compared with adults. A child’s age plays a significant role in protecting them from being influenced by commercial advertising, its attractiveness, and its impact on self-esteem and low self-satisfaction [48,50]. These findings contradict Martin et al. [73], who investigated the effects of very attractive models in advertisements on adolescent girls and boys and found no evidence of low self-esteem in the research sample. Other studies have also confirmed the presence of attractive body models in children’s media samples [74–75].

Hypotheses and Research Questions

The present study focused on the influence of different media, such as cartoons, films, and social media, on children’s body satisfaction. Previous research found that early childhood is a critical age during which social and cultural factors begin to contribute to the formation of dissatisfaction with body image in children aged 6 years and under [76]. The main hypothesis that underlies this study is that social media and the media affect Saudi children’s body image satisfaction. This hypothesis gave rise to the following research questions.

1. Are Saudi children satisfied with their body image?

2. Do social media and the media affect Saudi children’s body image satisfaction?

3. Are there differences among girls and boys in accepting their body image?

4. How do Saudi children targeted by this study look?

5. What body shape would children like?

6. Who are the most popular social media celebrities for girls and boys?

7. Which social media do children use most (girls/boys)?

The study sample comprised a group of 491 kindergarten children aged 5–7 years that were randomly chosen in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (246 girls, 50.1%; 245 boys, 49.9%). Most Saudi children have black-brown eyes, white-brown skin, and black or dark brown hair. Drawing on previous studies, the researcher designed a 26-item questionnaire with consideration of the unique Saudi context. Although validated questionnaires on body image are available, they cannot be applied to this context. Therefore, the author adapted some content from these questionnaires and scales in developing the present questionnaire to reflect the context of Saudi children. The questionnaire was reviewed by specialists who made revisions and suggested modifications as necessary. After incorporating this expert feedback, the revised questionnaire was presented to a specialist who approved its design. To ensure the accuracy of the items in measuring the variables, the validity of the tool was verified by a group of specialized faculty members and specialists from the College of Education, Department of Early Childhood at King Saud University. Adjustments were made in formulating some items, removing irrelevant items, and adding new items. After confirming the validity of the final scale, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to measure the reliability of responses. The internal consistency of the questionnaire in the study sample was 0.82, which indicated a high degree of reliability. Internal reliability, which measures the degree of correlation between different items of the questionnaire, was assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient, which was statistically significant at 0.01.

The questionnaire items investigated each child’s satisfaction with features of their external appearance, such as their teeth, eyes, hair, and body image; each item had three response options (“yes,” “no,” or “I don’t know”). Additional questions examined which social media celebrities children followed and whether they wanted to be famous. The questionnaire also included three open-ended questions covering the famous personality that children wanted to be like, the social media platforms they used, and the game characters that they wanted to be like. Each questionnaire item was read to the child by an adult (e.g., mother, father, caregiver), who recorded their responses without interference. The researcher secured informed consent from the children’s guardians to allow them to participate in this study and have their information used in any subsequent article(s).

In this study, children’s dissatisfaction with their body in the early childhood stage was defined as the image that children formed about their bodies compared with others and their preferences for ideal, slim body images (in terms of face, hair, muscles in boys, slim waists, and various other features) in the different social media platforms that they used. A body satisfaction scale was also designed, which included four illustrated options regarding eye color (black/brown/green/blue), hair color, hair shape, and external body shape. Children were required to respond to all questionnaire and body satisfaction scale items, and their responses to the questionnaire and the illustrated scale were compared.

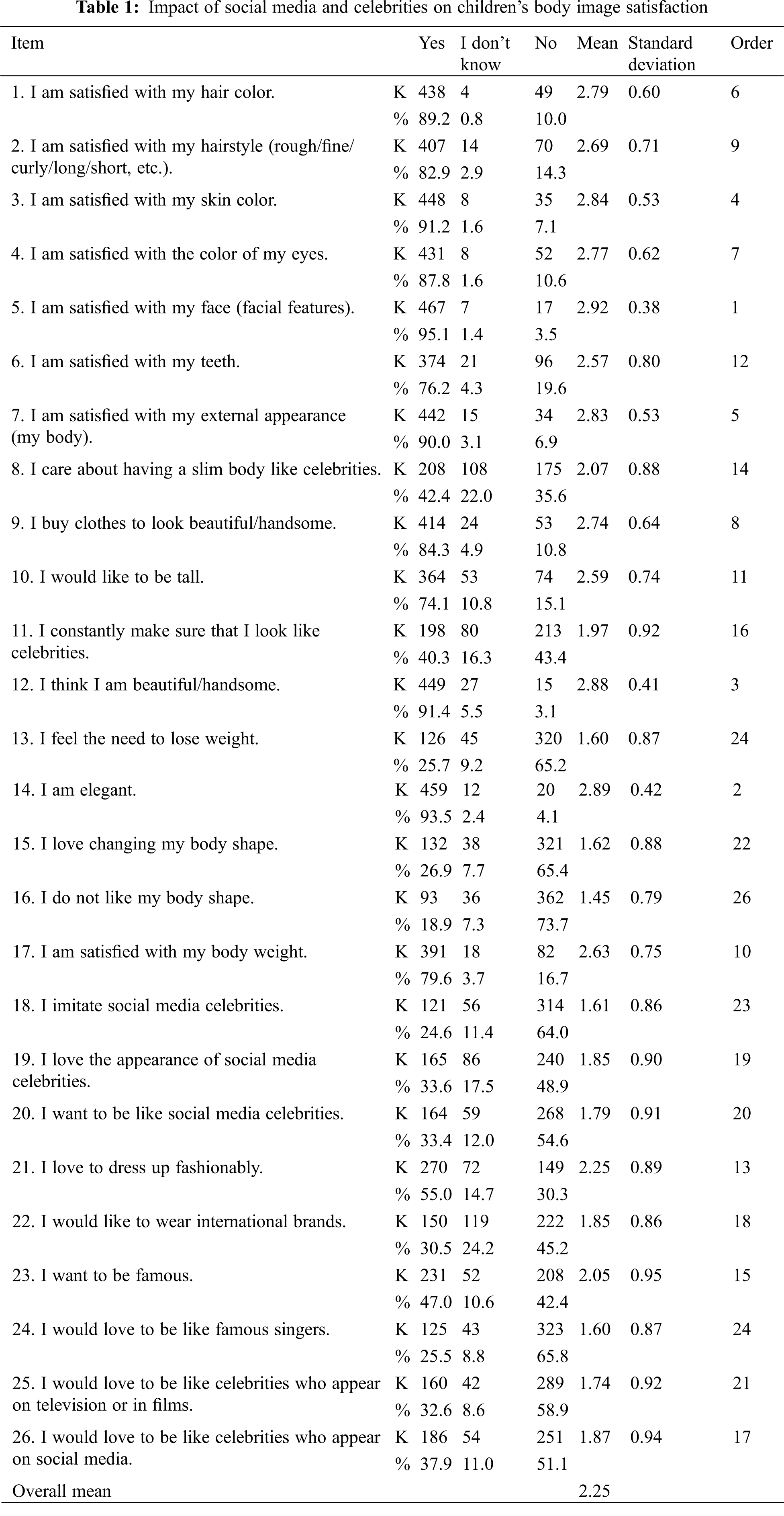

The results were organized according to the research questions. The first question was, “Are Saudi children satisfied with their body image?”. The children’s responses revealed that they were highly satisfied with the appearance of their face (95.1%, standard deviation [SD] 0.38) and apparel (93.5, SD 0.42). In addition, 91.4% of children believed that they were beautiful/handsome, 91.2% were satisfied with their skin color, and the overall level of satisfaction with their external appearance was 90.0% (SD 0.53). Table 1 shows that the children were highly satisfied with their external appearance as their responses to items 1–12 and 14 indicated high agreement. Conversely, many children disagreed with items 13, 15, and 16, which indicated they did not agree with they needed to lose weight and were happy with their external appearance.

In considering the second research question (i.e., “Do social media and the media affect children’s body image satisfaction?”) children’s responses showed that social media and other media did not affect children’s body image, as reflected in their responses to items 18, 20, 24, and 26. However, 37.9% of children wanted to become like social media celebrities (SD 0.94), 32.6% wanted to become like television and film personalities (SD 0.92), and 25.5% wanted to become like famous singers (SD 0.87). Overall, 47.0% of the children wanted to be famous (SD 0.95). In addition, 33.6% (SD 0.90) agreed with the item, “I like the appearance of social media celebrities”. This suggested that social media celebrities had an impact on many children and their desire to be famous and emulate them (range 25%–37%). The results also showed that some children were not satisfied with their external appearance (18.9%, SD 0.79), some children wanted to lose weight (25.7%, SD 0.87), and some wanted to change their shape (26.9%, SD 0.88) (Table 1).

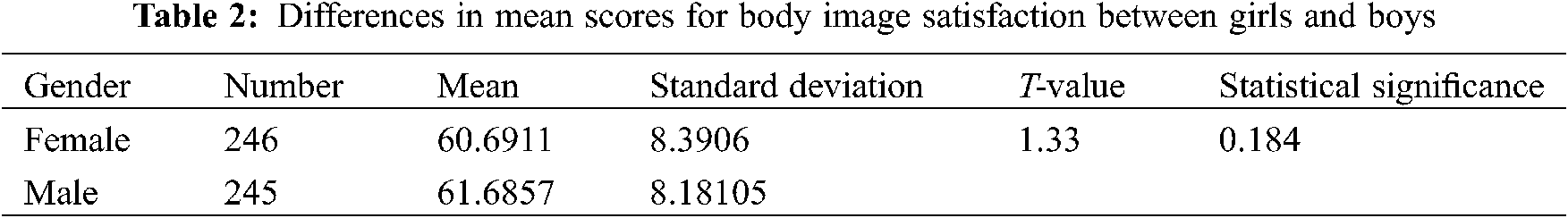

The third question concerned whether girls and boys differed in accepting their body image. The results showed there were no statistically significant differences between boys and girls in their satisfaction with their body image (Table 2).

The fourth question focused on children’s responses to items about their weight, hair color, skin color, and shape (external appearance). In total, 255 children (51.9%) identified as thin, 227 identified as average, and nine (1.8%) identified as overweight. Most children had black hair (n = 292, 59.5%) or dark brown hair (n = 161, 32.8%). Fewer children had blond (n = 30, 6.1%) or light brown (n = 7, 1.4%) hair, and one child had red hair (0.2%). In addition, 46.8% of the children (n = 230) were white/light-skinned, 45.8% (n = 225) had a medium skin tone, and 7.3% (n = 36) identified as dark-skinned.

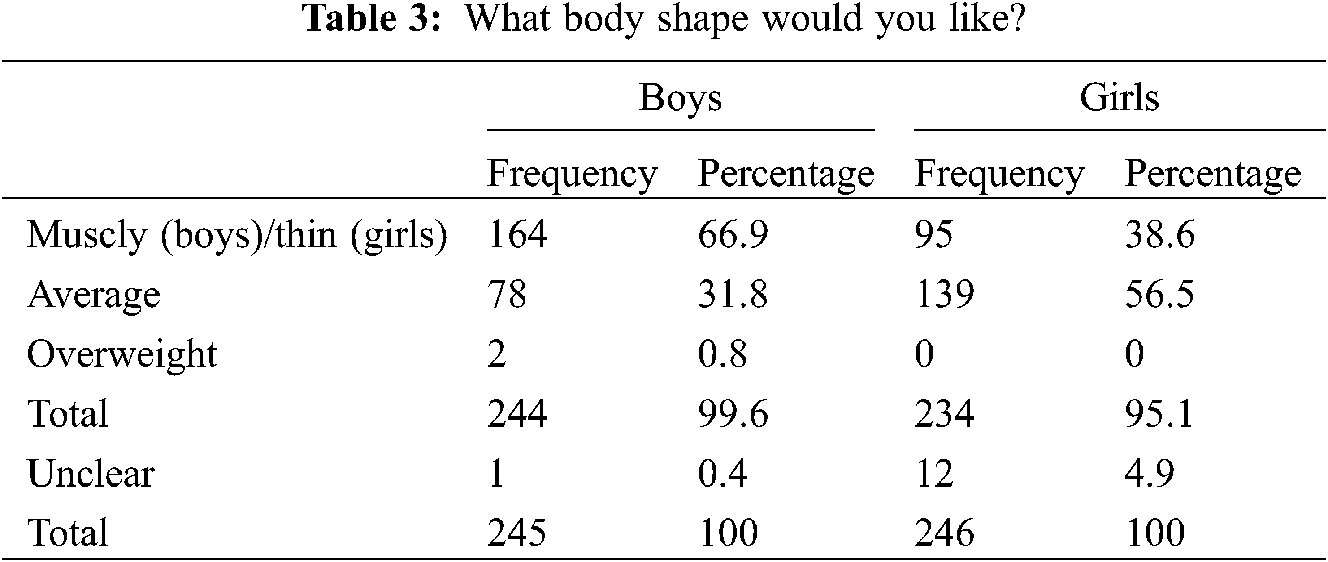

The fifth question focused on the body shape that children would like to have, based on responses to the illustrated scale (Table 3). Most boys (66.9%) desired a muscly body shape, and only 0.8% desired an overweight body shape. The results also showed that most girls (56.5%) wanted an average body shape, and 38.6% wanted to be slim. None of the girls wanted to be overweight, which confirmed the questionnaire results. When children were asked if they felt the need to lose weight, 65.2% said yes, although 79.6% were satisfied with their current body weight. This was also consistent with the children’s current weight as no children were reported as overweight. However, the impact of celebrities on children’s perception of weight was clear, as 42.4% of children answered “yes” when asked whether they wanted to be slim like celebrities.

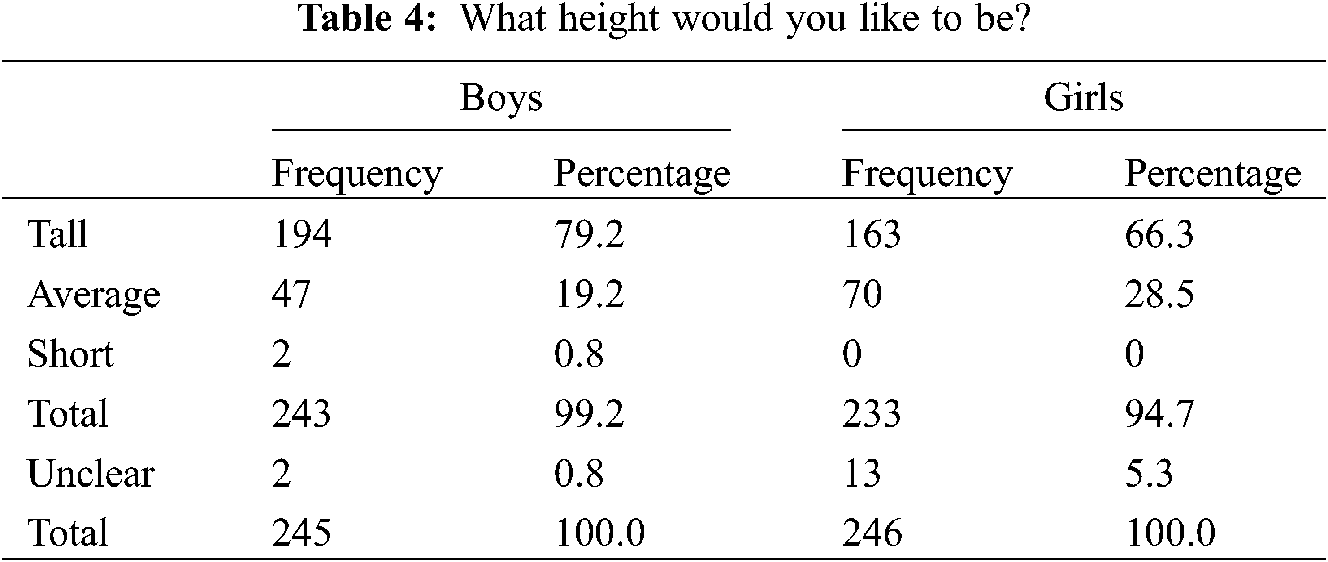

The results indicated that the majority of children wanted to be tall (boys 79.2%, girls 66.3%); 19.2% of boys and 28.5% of girls wanted to be of average height, and 0.8% of boys and none of the girls wanted to be short. These findings were consistent with those displayed in Table 1, where 74.1% of the children responded affirmatively to the statement, “I love being tall” (Table 4).

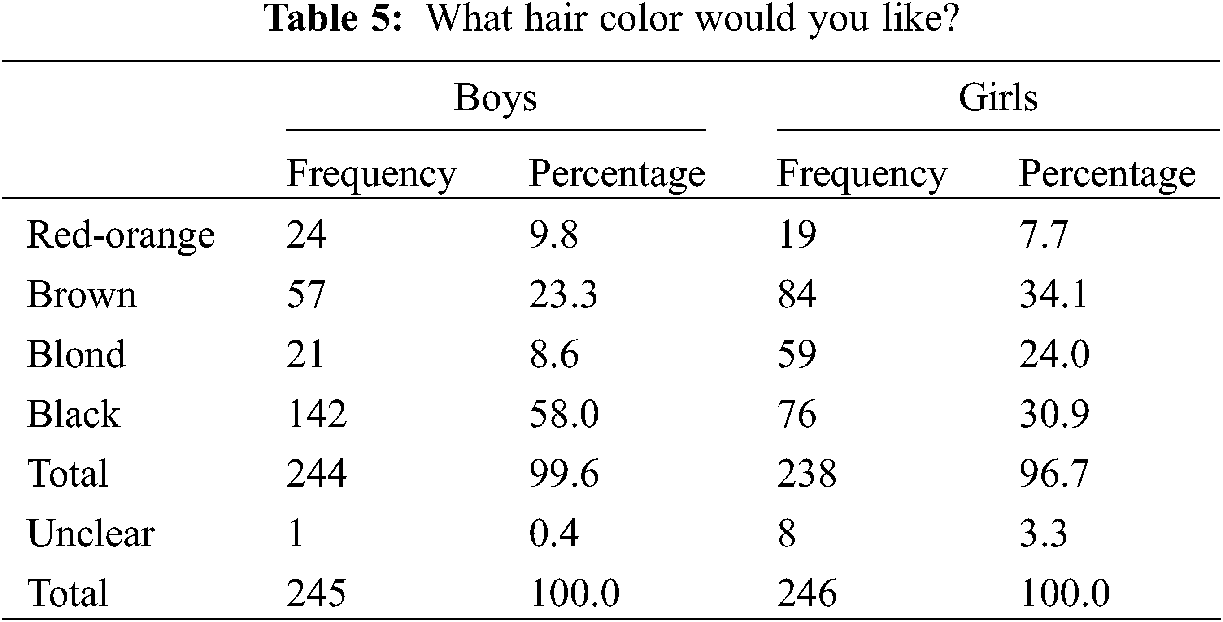

The items assessing children’s satisfaction with the color of their hair showed that 58.0% of boys wanted black hair, which was consistent with the findings shown in Table 1, whereas 23.3% wanted brown hair. Few boys wanted red-orange hair (9.8%) or blond hair (8.6%). Interestingly, 34.1% of girls wanted brown hair, which contradicted the results shown in Table 1. In addition, 30.9% of girls wanted black hair, 24.0% wanted blond hair, and 7.7% wanted red-orange hair. It was noteworthy that the majority of boys and girls had black or brown hair, demonstrating a difference and dissatisfaction among girls regarding their hair color (Table 5).

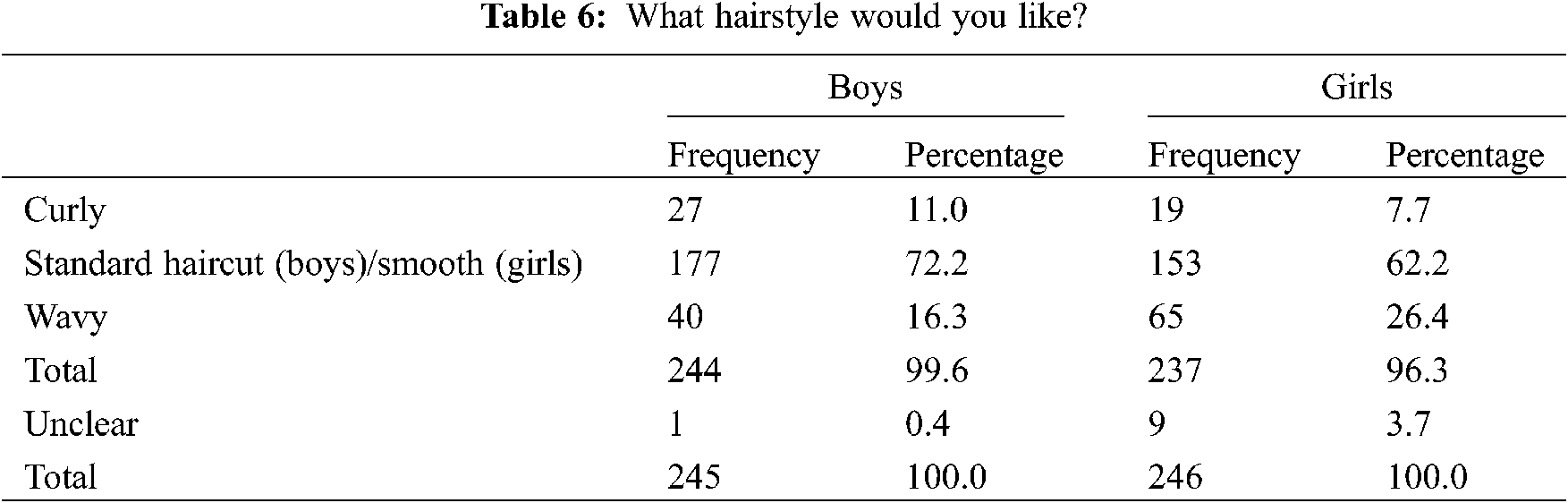

Children’s responses about hair style revealed that 72.2% of boys wanted a standard hairstyle, 16.3% wanted wavy hair, and 11.0% wanted curly hair. Among girls, 62.2% wanted smooth hair, 26.4% wanted wavy hair, and 7.7% wanted curly hair. Girls’ responses to the illustrated scale questions regarding their body satisfaction differed from their responses to the questionnaire in Table 1, where 82.9% responded positively to the statement, “I am satisfied with my hairstyle”. Their preference for hair style on the illustrated scale were different, which indicated dissatisfaction with their hairstyle when using this scale to measure their body satisfaction (Table 6).

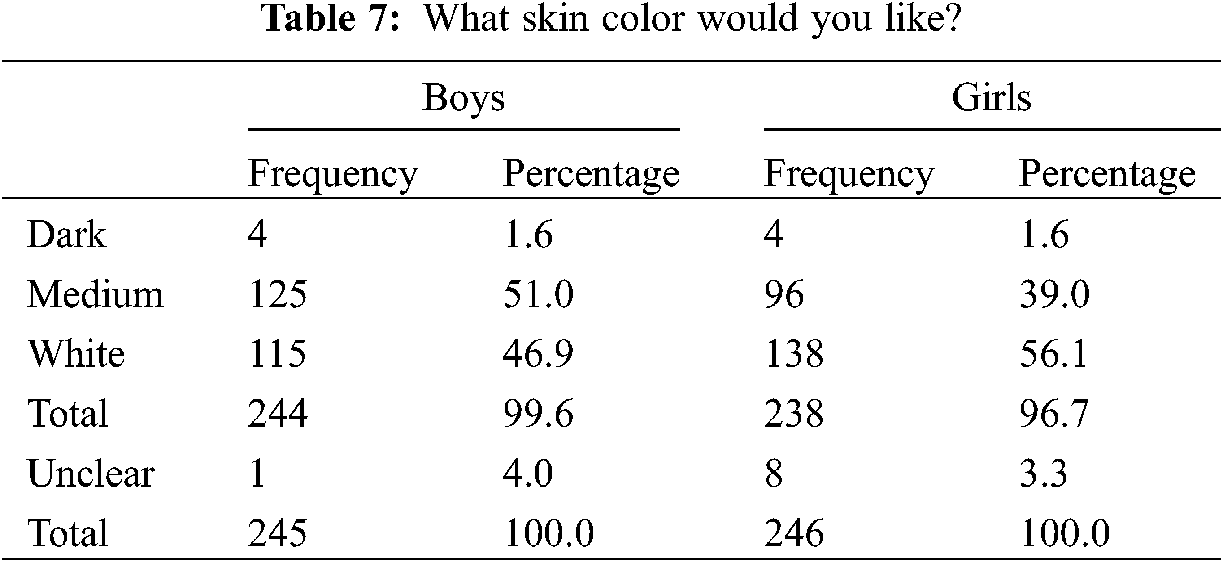

The children’s responses to the illustrated scale on body satisfaction showed that 51% of boys wanted a medium skin color, 46.9% wanted white skin, and 1.6% wanted brown skin. Unlike the boys, 56.1% of girls wanted their skin color to be white, 39.0% wanted a medium skin color, and 1.6% wanted their skin color to be brown. These findings were consistent with those of Table 1, where 91.2% of the children agreed with the statement, “I am satisfied with my skin color” (Table 7).

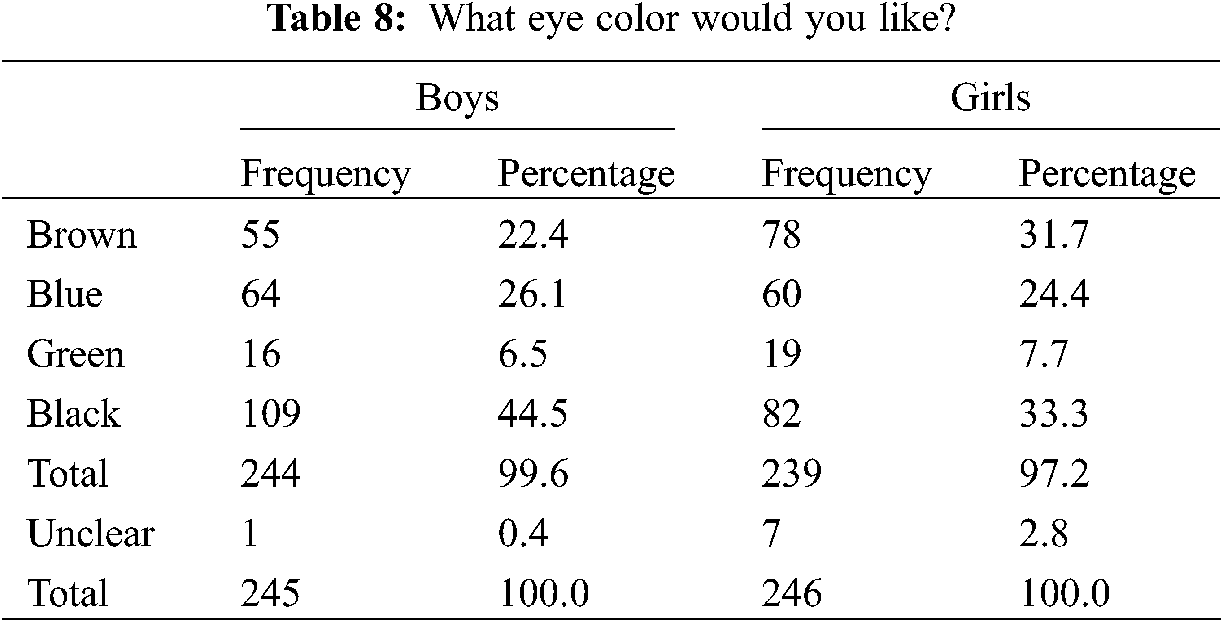

Children’s responses to the illustrated scale showed that 44.5% of boys wanted black eye color, 26.1% wanted blue eyes, 22.4% wanted brown eyes, and 6.5% wanted green eyes. Similarly, 33.3% of girls wanted their eyes to be black, 31.7% wanted their eyes to be brown, 24.4% wanted their eyes to be blue, and 7.7% wanted green eyes. These findings were consistent with the children’s responses to the corresponding statement in the questionnaire (“I am satisfied with the color of my eyes”; 87.8%). However, some children (boys 32.6%, girls 32.1%) expressed a desire to have a different eye color from their own, which may show the impact of social media on children’s body satisfaction in terms of eye color, as blue and green eyes are currently widely admired in Saudi society and children in Riyadh are mostly black- or brown-eyed (Table 8).

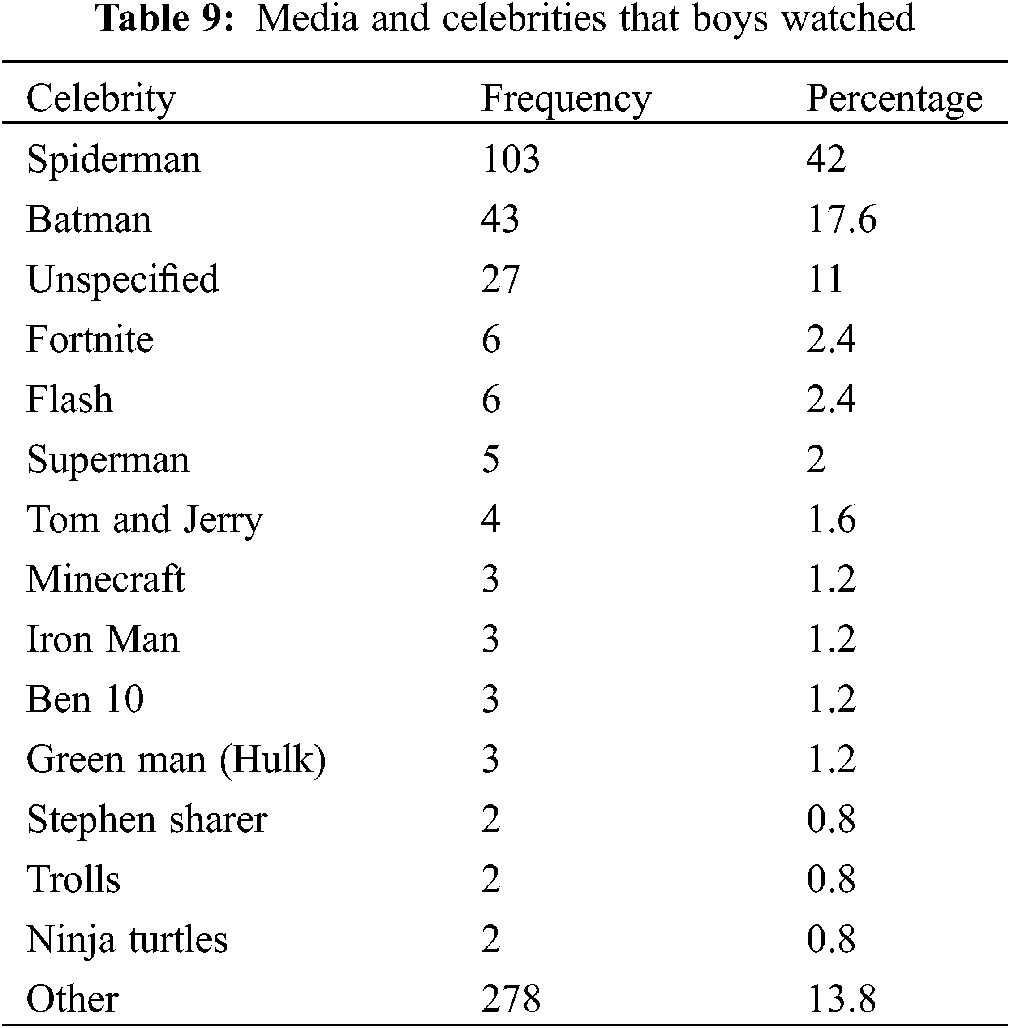

Analysis of children’s responses to sixth question (i.e., “Who are the most popular social media celebrities for girls and boys?”) revealed that boys and girls watched certain celebrities and wanted to be like some of them. For example, 42.0% of boys were influenced by the Spiderman character, 17.6% were influenced by Batman, 2.4% were influenced by Fortnite, 0.4%–2.4% were influenced by other characters, and 11.0% were not influenced by a specific character. The overall percentage of boys influenced by film characters was 64.4%.

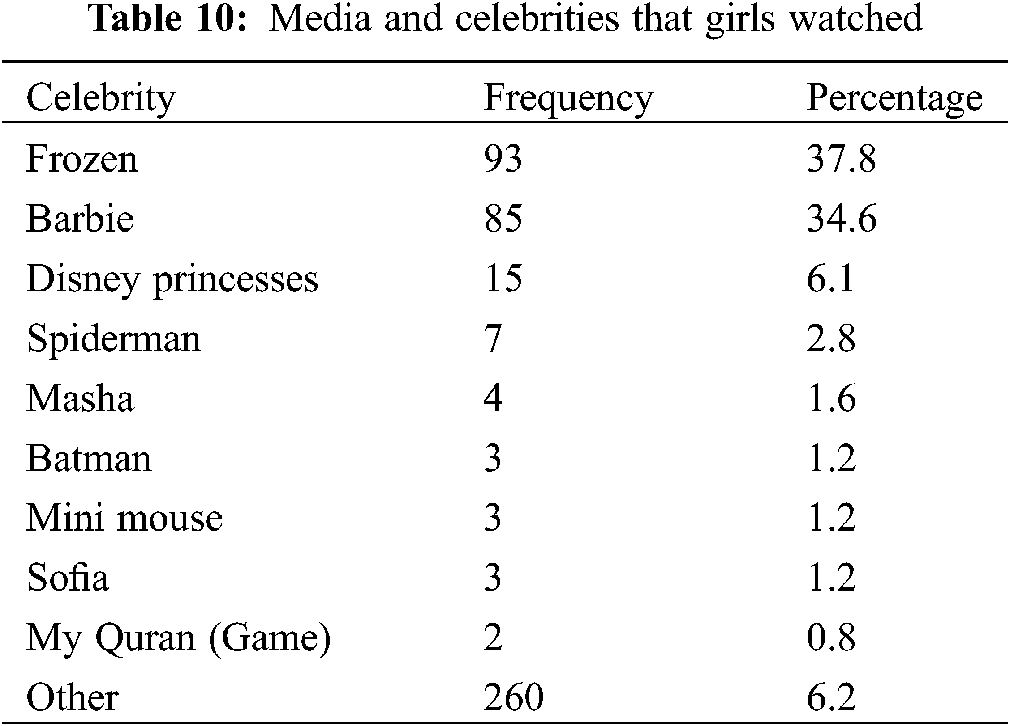

Many girls (37.8%) were influenced by the lead character from Frozen (this character was singled out from the other Disney princesses because of its frequency), 34.6% were influenced by Barbie, 4.1% were influenced by the Disney princesses, and 6.5% were not influenced by a specific character (0.4%–2.8% were influenced by other characters). That is, the total percentage of girls influenced by media characters was 80.3%, which was high compared with boys. These results appeared to contradict the questionnaire results about imitating celebrities and their desire to be like them. The children’s responses to the questionnaire revealed that 64.0% disagreed with the statement, “I imitate celebrities”, 48.9% answered “no” to the statement, “I like the appearance of social media celebrities”, and 65.8% responded “no” to the statement, “I want to be like famous singers”. In addition, 58.9% answered “no” to the statement, “I want to be as famous as people on television and in films”, and 51.1% responded “no” to the statement, “I want to be as famous as the celebrities on social media” (11.0% responded “I don’t know”) (Tables 9 and 10).

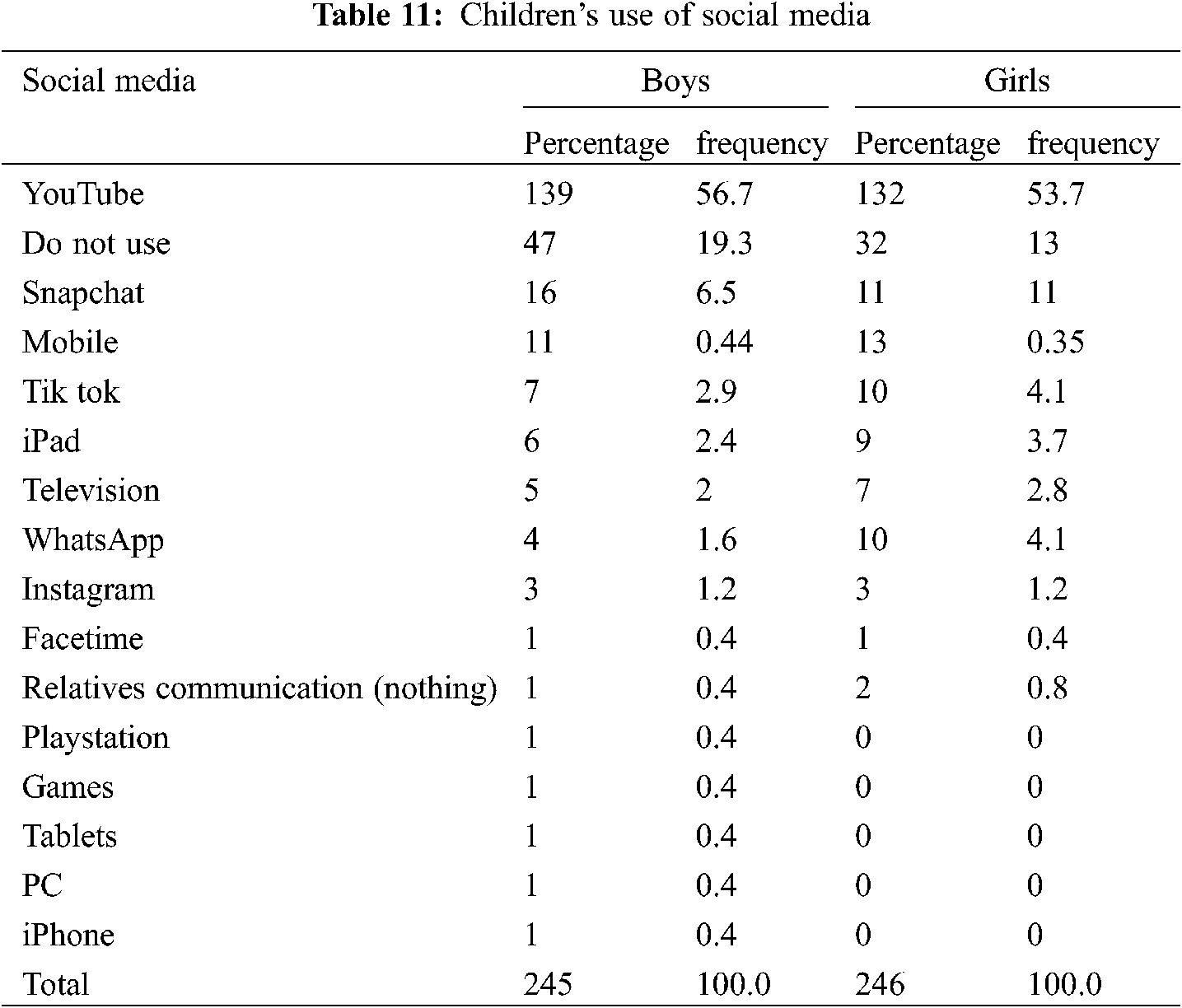

Analysis of responses relating to the seventh question concerning children’s use of social media showed that 56.7% of boys and 53.7% of girls used YouTube, 6.5% of boys and 11.0% of girls used Snapchat, 2.9% of boys and 4.1% of girls used Tik Tok, and 4.1% of girls used WhatsApp. In addition, 19.2% of boys and 13.0% of girls did not use social media, and 0.4%–2.4% of boys and 0.4%–3.7% of girls used other social media and media platforms (Table 11).

This study revealed high satisfaction among children aged 5–7 years regarding their body (90.0%), their weight (79.6%), and their shape (73.7%). Items 1–12 of the questionnaire showed children had high satisfaction with aspects of their bodies. However, significant percentages of children wanted to be famous like social media celebrities (37.9%), television and film celebrities (32.6%), and singers (25.5%). Previous studies indicated that young children are influenced by social media and celebrities [35,36], although Tadena et al. [77] concluded that the younger children are, the fewer complaints they have about their appearance and body dissatisfaction. It is impossible to ignore the influence of social media in modern society [78]. This influence is particularly clear among adolescents and teenagers who have grown up with this technology alongside traditional media [79,80], which was also confirmed among younger children in this study. This suggests that parents, social media celebrities, and filmmakers are responsible to present positive content for young children because of the strong influence they have on children.

The present study showed differences between children’s responses to the illustrated scale of body satisfaction and the research questionnaire, which was consistent with Cm et al. [64] who stated that we must pay attention to the research tools used in data collection. The comparison between the illustrated scale for body satisfaction and children’s responses to the questionnaire (Table 1) revealed that boys desired a muscly external body shape, whereas the majority of girls wanted an average body shape, suggesting that boys were highly influenced by strong characters they watched (Spiderman/Batman/Fortnite). Smith et al. [81] analyzed children’s television programs from 2006 to 2011 and found that masculine characters that young boys tended to associate with were muscular, which was confirmed by Da et al. and Petrie et al. [40,41]. Neither girls nor boys wanted to be overweight as shown in the illustrated scale of body satisfaction, which was also consistent with the children’s responses to the questionnaire (i.e., they were satisfied with their body weight, although they cared about having bodies like celebrities; 42.4%).

The influence of social media and films on children was clear in this study as both boys and girls preferred to be slim. Children showed strong admiration for social media celebrities (37.9%), and television and film characters such as Spiderman, Batman, Frozen, Barbie, and Disney princesses were also influential (64.4% of boys and 80.3% of girls), which was a higher percentage than for social media celebrities. Brown [82] indicated that characters such as Spiderman, Young Justice, and the Green Lantern were popular, especially among young boys, although these characters were created for older children. Media-produced films and imaginary characters have a major influence on children’s development and behavior and are associated with children’s play and imagination, where children imitate and play the roles of superheroes [78,83].

Marcolino et al. suggested that roleplay and stories about superheroes can have a significant influence on the context and themes of children’s imaginative play because superhero stories present relationships between the characters in a lively manner. Furthermore, when a child is playing a role, they emulate the strengths or powers of that superhero, believe in them as strong role models and feel fearless and ready to deal with any situation [84]. Moreover, the present study revealed that Barbie had a significant impact on girls (34.6%). As the sample respondents were aged 5–7 years, the influence of Barbie appeared to arise at an early age, which was consistent with the conclusions of Dittmar et al. [24]. Barbie dolls’ influence is also associated with the influence of society and of television, films, and social media celebrities on children.

The children’s responses in this study also indicated they desired to be tall. None of the girls and few boys (0.8%) expressed a desire to be short. This finding supported Nesbitt et al. [35], who found that when children were exposed to tall and short Barbie toys, the taller Barbie was classified as highly desirable and attractive. Close attention should therefore be paid to the hidden and apparent messages that are implied in the toys and social media that influence children of both sexes in terms of the desire to be thin, muscly, and tall. This result was also consistent with other studies, including one study conducted by the Girl Scout Research Institute (2010) among girls aged 10–17 years, which found 48% of girls wished to be as thin as fashion magazine models. Furthermore, in a study conducted by the rToday Show and AOL.com (2014), 80% of female teenage respondents compared their body image with that of celebrities, and almost 50% expressed that celebrity bodies made them feel dissatisfied with their own body. The responses of children in the present study also reflected the level of social and cultural change among children in terms of social media celebrities and their desire to become as famous as they were, rather than be as famous as television, cinema, and music celebrities. This highlighted the strong influence social media celebrities have on shaping children’s behavior and body satisfaction. Researchers focusing on the influence of the media on children’s body image have noted that the media encourages girls to be thin and sends implied messages regarding female beauty standards of being young, beautiful, and thin. For example, a content review of women’s fashion and fitness magazines found that most models were thin and tall (Children, Teens, Media, and Body Image | Common Sense Media, n.d.).

The present study also revealed that girls were influenced by celebrities and media regarding their hair color. Approximately 24.0% of girls wanted blond hair and blue eyes (24.4%) or green eyes (7.7%), whereas fewer boys showed a desire for blond hair (8.6%), blue eyes (26.1%), and green eyes (6.5%). The influence of celebrities and media on girls appeared again in their desire to have smooth hair (62.2%), whereas boys’ responses showed that they were satisfied with their usual haircut (72.2%). In the Arab world in general and Saudi society in particular, some children admire blond hair and blue and green eyes as these colors are uncommon and unusual in their society, where most of the population have black or brown hair and eyes. This finding was supported by those of Dittmar et al. [24] and Nesbitt et al. [35].

The present results were also consistent with recent empirical evidence demonstrating that young girls may partake in upward social comparisons with physiques that are considered unrealistic or not like their own. Looking at the characters that girls in this study admired, it was found that the majority of characters had light-colored hair and eyes and soft hair, such as Frozen (37.8%), Barbie (34.6%), and Disney princesses (4.1%). This also supported previous views [85,86] that stated that girls in the Arab world want to be different in appearance from members of their society.

This study highlighted that YouTube was the most used social media platform among both girls and boys (53.7% and 56.7%, respectively). Some children (boys 19.2%, girls 13%) did not use any social media platforms; 6.5% of boys and 11% of girls used the Snapchat platform, while the other social media platforms had even lower response rates. These results were similar to those of Coyne et al. [84]. YouTube is easily accessed as there is no need for children to sign up and create an account as with other social media platforms. Snapchat is a modern application that enables the follower to watch a clip within 24 h before it is deleted. It also allows users to communicate via text, voice messages, and video calls, and may be used by children, especially those who do not have telephone numbers, on mobile or iPad devices. Statistics published by the International Telecommunication Union in 2016 showed that developing countries represent the majority of Internet users (2.5 billion) compared with 1 billion users in developed countries. Statistics have also revealed that one in every three Internet users in the world is a child. Currently, the Internet is the main means by which children collaborate, share, learn, and play [87]. These means of communication have become more influential on children than the traditional media [88]. However, there is a lack of research on the role these new media play in the life of young children under the age of 13 years. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the relationship between distinct media user types and social displacement among children under age 13 years. A previous study involving 1,117 Norwegian schoolchildren aged 7–12 years assessed their computer game-playing habits and use of computers, the Internet, mobile phones, and television. The results indicated four specific user types reflecting children’s various uses of new media: a) advanced users, b) offline gamers, c) instrumental users, and d) low users. Some indications of displacement were found between TV, reading, and drawing and between new media use and participation in organized sports activities. At the same time, clear indications supported the “more is more” hypothesis, which predicts that active media users will be active children.

Finally, this study found no statistically significant differences in body satisfaction between girls and boys, unlike previous studies that found girls paid more attention to their body than boys [88–91]. Longitudinal studies in the Arab world, particularly in Saudi Arabia, are needed to offer rigorous investigation of this topic.

Acknowledgement: We thank Audrey Holmes, MA, from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study. The researcher has the data of this research, used only for research purpose and all data are confidential.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Margulies, A. S., Floyd, R. G., Hojnoski, R. L. (2008). Body size stigmatization: An examination of attitudes of African American preschool-age children attending head start. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(5), 487–496. DOI 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Eisenberg, M. E., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., Perry, C. (2005). The role of social norms and friends’ influences on unhealthy weight-control behaviors among adolescent girls. Social Science & Medicine, 60(6), 1165–1173. DOI 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Harriger, J. A., Calogero, R. M., Witherington, D. C., Smith, J. E. (2010). Body size stereotyping and internalization of the thin ideal in preschool girls. Sex Roles, 63(9–10), 609–620. DOI 10.1007/s11199-010-9868-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Musher-Eizenman, D. R., Holub, S. C., Miller, A. B., Goldstein, S. E., Edwards-Leeper, L. (2004). Body size stigmatization in preschool children: The role of control attributions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 29(8), 613–620. DOI 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kardiner, A. (1939). >Psychotherapy. In: Schilder, P., Psychoanal Q, vol. 8, pp. 337. New York: W. W. Norton &: Co., Inc. [Google Scholar]

6. PubMed (1998). Body image in anorexia nervosa. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3072049/. [Google Scholar]

7. Grogan, S. (2007). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. 2nd (ed.). UK: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

8. Mutale, G., Andrew, D., James, S., Rebecca, L. (2016). Development of a body dissatisfaction scale assessment tool. Development of a Body Dissatisfaction Scale Assess Tool, 13, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

9. Burrowes, N. (2013). Body image-a rapid evidence assessment of the literature. A project on behalf of the Government Equalities Office. [Google Scholar]

10. Cash, T. (2004). Body image: Past, present, and future. Body Image, 1, 1–5. DOI 10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00011-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Watson, J. (1928). The ways of behaviorism. New York and London: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

12. Skinner, B. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

13. Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. https://www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html. [Google Scholar]

14. Piaget, J. (1941). The child’s conception of number. https://www.biblio.com/the-childs-conception-of-by-piaget-jean/work/408041. [Google Scholar]

15. Piaget, J. (1969). The psychology of the child. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

16. Vygotsky, L. S., Cole, M., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E. (1978). Mind in Society. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674576292. [Google Scholar]

17. Kohlberg, L. A. (1966). A cognitive developmental analysis of children’s sex role concepts and attitudes. In: The Development of sex differences. pp. 82–173. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

18. Lambrou, C., Veale, D., Wilson, G. (2012). Appearance concerns comparisons among persons with body dysmorphic disorder and nonclinical controls with and without aesthetic training. Body Image, 9(1), 86–92. DOI 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Buhlmann, U., Teachman, B. A., Naumann, E., Fehlinger, T., Rief, W. (2009). The meaning of beauty: Implicit and explicit self-esteem and attractiveness beliefs in body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(5), 694–702. DOI 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.02.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Markus, H. (1977). Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(2), 63–78. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.35.2.63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Tatangelo, G. L., Ricciardelli, L. A. (2017). Children’s body image and social comparisons with peers and the media. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(6), 776–787. DOI 10.1177/1359105315615409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Leahey, T. M., Crowther, J. H., Mickelson, K. D. (2007). The frequency, nature, and effects of naturally occurring appearance-focused social comparisons. Behavior Therapy, 38(2), 132–143. DOI 10.1016/j.beth.2006.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pesa, J. A., Syre, T. R., Jones, E. (2000). Psychosocial differences associated with body weight among female adolescents: the importance of body image. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26(5), 330–337. DOI 10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00118-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dittmar, H., Halliwell, E., Ive, S. (2006). Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 283–292. DOI 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Meng, J., Bissell, K. L., Pan, P. L. (2015). YouTube video as health literacy tool: A test of body image campaign effectiveness. Health Mark Q, 32(4), 350–366. DOI 10.1080/07359683.2015.1093883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yamamiya, Y., Cash, T. F., Melnyk, S. E., Posavac, H. D., Posavac, S. S. (2005). Women’s exposure to thin-and-beautiful media images: Body image effects of media-ideal internalization and impact-reduction interventions. Body Image, 2(1), 74–80. DOI 10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Choma, B. L., Foster, M. D., Radford, E. (2007). Use of objectification theory to examine the effects of a media literacy intervention on women. Sex Roles, 56(9–10), 581–590. DOI 10.1007/s11199-007-9200-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Dion, K. K. (1973). Young children’s stereotyping of facial attractiveness. Developmental Psychology, 9(2), 183–188. DOI 10.1037/h0035083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Vermeir, I., van de Sompel, D. (2014). Assessing the what is beautiful is good stereotype and the influence of moderately attractive and less attractive advertising models on self-perception, ad attitudes, and purchase intentions of 8–13-year-old children. Journal of Consumer Policy, 37(2), 205–233. DOI 10.1007/s10603-013-9245-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Buunk, A. P., Dijkstra, P. (2011). Does attractiveness sell? Women’s attitude toward a product as a function of model attractiveness, gender priming, and social comparison orientation. Psychology & Marketing, 28(9), 958–973. DOI 10.1002/mar.20421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gaballero, M. J. (1989). Using physical attractiveness as an advertising tool. Journal of Advertising Research, 29(4), 16–22. [Google Scholar]

32. Smith, S. M., McIntosh, W. D., Bazzini, D. G. (1999). Are the beautiful good in hollywood? An investigation of the beauty-and-goodness stereotype on film. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 21(1), 69–80. DOI 10.1207/s15324834basp2101_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kuther, T. L., McDonald, E. (2004). Early adolescents’ experiences with, and views of barbie. Adolescence, 39, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

34. Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

35. Nesbitt, A., Sabiston, C. M., deJonge, M., Solomon-Krakus, S., Welsh, T. N. (2019). Barbie’s new look: Exploring cognitive body representation among female children and adolescents. PLoS One, 14(6), e0218315. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0218315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Coyne, S. M., Linder, J. R., Rasmussen, E. E., Nelson, D. A., Birkbeck, V. (2016). Pretty as a princess: Longitudinal effects of engagement with disney princesses on gender stereotypes, body esteem, and prosocial behavior in children. Child Development, 87(6), 1909–1925. DOI 10.1111/cdev.12569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Esnaola, I., Rodríguez-Fernández, A., Goñi, A. (2009). Body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures: Gender and age differences. Salud Ment México, 33(1), 21–29. [Google Scholar]

38. Lunde, C., Frisén, A., Hwang, C. P. (2007). Ten-year-old girls’ and boys’ body composition and peer victimization experiences: Prospective associations with body satisfaction. Body Image, 4(1), 11–28. DOI 10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Menzel, J. E., Schaefer, L. M., Burke, N. L., Mayhew, L. L., Brannick, M. T. et al. (2010). Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Body Image, 7(4), 261–270. DOI 10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Petrie, T. A., Greenleaf, C., Martin, S. (2010). Biopsychosocial and physical correlates of middle school boys’ and girls’ body satisfaction. Sex Roles, 63(9−10), 631–644. DOI 10.1007/s11199-010-9872-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. da, F., J, L., La, P. (2007). Interest in cosmetic surgery and body image: Views of men and women across the lifespan. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 120(5), 1407–1415. DOI 10.1097/01.prs.0000279375.26157.64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Rasmussen, F., Eriksson, M., Nordquist, T. (2007). Bias in height and weight reported by Swedish adolescents and relation to body dissatisfaction: The COMPASS study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 61(7), 870–876. DOI 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wardle, J., Haase, A. M., Steptoe, A. (2005). Body image and weight control in young adults: International comparisons in university students from 22 countries. International Journal of Obesity, 30(4), 644–651. DOI 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Michael, S. L., Wentzel, K., Elliott, M. N., Dittus, P. J., Kanouse, D. E. et al. (2014). Parental and peer factors associated with body image discrepancy among fifth-grade boys and girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(1), 15–29. DOI 10.1007/s10964-012-9899-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ricciardelli, L. A., McCabe, M. P., Lillis, J., Thomas, K. (2006). A longitudinal investigation of the development of weight and muscle concerns among preadolescent boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(2), 177–187. DOI 10.1007/s10964-005-9004-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. van den Berg, P. A., Mond, J., Eisenberg, M., Ackard, D., Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2010). The link between body dissatisfaction and self-esteem in adolescents: Similarities across gender, age, weight status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(3), 290–296. DOI 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Maloney, M. J., McGuire, J. B., Daniels, S. R. (1988). Reliability testing of a children’s version of the eating attitude test. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(5), 541–543. DOI 10.1097/00004583-198809000-00004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Tiggemann, M. (2003). Media exposure, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Television and magazines are not the same! European Eating Disorders Review, 11, 418–430. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Eder, R. A., Mangelsdorf, S. C. (1997). The emotional basis of early personality development: Implications for the emergent self-concept. In: Handbook of personality psychology. pp. 209–240. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

50. Marsh, H., Ellis, L., Craven, R. (2002). How do preschool children feel about themselves? Unraveling measurement and multidimensional self-concept structure. Developmental Psychology, 38(3), 376–393. DOI 10.1037/0012-1649.38.3.376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Davison, K. K., Birch, L. L. (2002). Processes linking weight status and self-concept among girls from ages 5 to 7 years. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 735–748. DOI 10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Gardner, R. M., Friedman, B. N., Jackson, N. A. (1999). Body size estimations, body dissatisfaction, and ideal size preferences in children six through thirteen. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(5), 603–618. DOI 10.1023/A:1021610811306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Clark, L., Tiggemann, M. (2007). Sociocultural influences and body image in 9 to 12-year-old girls: The role of appearance schemas. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 36(1), 76–86. DOI 10.1080/15374410709336570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Ata, R., Ludden, A., Lally, M. (2006). The effects of gender and family, friend, and media influences on eating behaviors and body image during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(8), 1024–1037. DOI 10.1007/s10964-006-9159-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Pacione, S. M., Pathak, A., Patel, S., Tremblay, L., Welsh, T. N. (2018). Body schema activation for self-other matching in youth. Cognitive Development, 48(1), 155–166. DOI 10.1016/j.cogdev.2018.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Welsh, T., McDougall, L., Paulson, S. (2014). The personification of animals: Coding of human and nonhuman body parts based on posture and function. Cognition, 132(3), 398–415. DOI 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Smolak, L., Murnen, S. K. (2011). The sexualization of girls and women as a primary antecedent of self-objectification. self-objectification in women: Causes, consequences, and counteractions, pp. 53–75. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

58. Tremblay, L., Lovsin, T., Zecevic, C., Larivière, M. (2011). Perceptions of self in 3–5-year-old children: A preliminary investigation into the early emergence of body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 8(3), 287–292. DOI 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Hohlstein, L. A., Smith, G. T., Atlas, J. G. (1998). An application of expectancy theory to eating disorders: Development and validation of measures of eating and dieting expectancies. Psychological Assessment, 10(1), 49–58. DOI 10.1037/1040-3590.10.1.49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Grabe, S., Ward, L., Hyde, J. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460–476. DOI 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Want, S. C. (2009). Meta-analytic moderators of experimental exposure to media portrayals of women on female appearance satisfaction: Social comparisons as automatic processes. Body Image, 6(4), 257–269. DOI 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.07.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Anschutz, D. J., Engels, R. C. M. E. (2010). The effects of playing with thin dolls on body image and food intake in young girls. Sex Roles, 63(9–10), 621–630. DOI 10.1007/s11199-010-9871-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Hayes, S., Tantleff-Dunn, S. (2010). Am I too fat to be a princess? Examining the effects of popular children’s media on young girls’ body image. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28(2), 413–426. DOI 10.1348/026151009X424240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Cm, N., Fm, C., Jff, M., Ffdr, M., Mec, F. (2017). Body image in childhood: An integrative literature review. https://www.scielo.br/j/rpp/a/tQRHQkMJYCJ3DsyxMRVp87M/?lang=en&format=pdf. [Google Scholar]

65. Wedwick, L., Latham, N. (2013). Socializing young readers: A content analysis of body size images in caldecott medal winners. https:///paper/Socializing-Young-Readers%3A-A-Content-Analysis-of-in-Wedwick-Latham/57903ba0f9b0c5eb7c093a1e688bcf3b7b671abd. [Google Scholar]

66. Huang, G. C., Unger, J. B., Soto, D., Fujimoto, K., Pentz, M. A. et al. (2014). Peer influences: The impact of online and offline friendship networks on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(5), 508–514. DOI 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Tiggemann, M., Slater, A. (2013). NetGirls: The Internet, Facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorder, 46(6), 630–633. DOI 10.1002/eat.22141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Grabe, S., Ward, L., Hyde, J. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460–476. DOI 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Want, S. C. (2009). Meta-analytic moderators of experimental exposure to media portrayals of women on female appearance satisfaction: Social comparisons as automatic processes. Body Image, 6(4), 257–269. DOI 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.07.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Blond, A. (2008). Impacts of exposure to images of ideal bodies on male body dissatisfaction: A review. Body Image, 5(3), 244–250. DOI 10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Hatoum, I. J., Belle, D. (2004). Mags and abs: Media consumption and bodily concerns in men. Sex Roles, 51(7/8), 397–407. DOI 10.1023/B:SERS.0000049229.93256.48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Martin, M. C., Gentry, J. W. (1997). Stuck in the model trap: The effects of beautiful models in ads on female pre-adolescents and adolescents. Journal of Advertising, 26(2), 19–33. DOI 10.1080/00913367.1997.10673520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Martin, M. C., Kennedy, P. F. (1993). Advertising and social comparison: Consequences for female preadolescents and adolescents. Psychology & Marketing, 10, 513–530. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Ruiz, C., Conde, E., Torres, E. (2005). Importance of facial physical attractiveness of audiovisual models in descriptions and preferences of children and adolescents. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 101(1), 229–243. DOI 10.2466/pms.101.1.229-243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Harrison, K. (2000). Television viewing, fat stereotyping, body shape standards, and eating disorder symptomatology in grade school children. Communication Research, 27(5), 617–640. DOI 10.1177/009365000027005003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Sands, E. R., Wardle, J. (2003). Internalization of ideal body shapes in 9–12-year-old girls. International Journal of Eating Disorder, 33, 193–204. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1098-108X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Tadena, S., Kang, S., Kim, S. J. (2020). The influence of social media affinity on eating attitudes and body dissatisfaction in Philippine adolescents. Child Health Nursing Research, 26(1), 121–129. DOI 10.4094/chnr.2020.26.1.121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Gerlich, R. N., Browning, L., Westermann, L. (2010). The social media affinity scale: Implications for education. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 3(11), 35–42. DOI 10.19030/cier.v3i11.245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Khan, G. F., Swar, B., Lee, S. K. (2014). Social media risks and benefits: A public sector perspective. Social Science Computer Review, 32(5), 606–627. DOI 10.1177/0894439314524701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Nelson, S. C., Kling, J., Wängqvist, M., Frisén, A., Syed, M. (2018). Identity and the body: Trajectories of body esteem from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 54(6), 1159–1171. DOI 10.1037/dev0000435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Smith, A. R., Hames, J. L., Joiner, T. E. (2013). Status update: Maladaptive facebook usage predicts increases in body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorder, 149(1–3), 235–240. DOI 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Brown, L. M. (2009). Packaging boyhood: Saving our sons from superheroes, slackers, and other media stereotypes. New York, USA: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

83. Boyatzis, C. J. (1997). Of power rangers and V-chips. Young Child, 52, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

84. Coyne, S., Linder, J., Rasmussen, E., Nelson, D., Collier, K. (2014). It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a gender stereotype!: Longitudinal associations between superhero viewing and gender stereotyped play. Sex Roles, 70(9–10), 416–430. DOI 10.1007/s11199-014-0374-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Harris, P. L. (2000). The work of the imagination. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/child-psychology-and-psychiatry-review/article/p-l-harris-the-work-of-the-imagination-oxford-blackwell-publishers-2000-pp-222-1499-pb/FE3243D5543D62A78A7E688012D74C56. [Google Scholar]

86. Marcolino, S., Mello, S. A. (2015). Role play themes in early childhood education. Psicologia, Ciência e Profissão, 35(2), 457–472. DOI 10.1590/1982-370302432013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Common Sense Media, Children, Teens, Media, and Body Image (2015). https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/children-teens-media-and-body-image. [Google Scholar]

88. Dennis, E., Martin, J., Wood, R. (2017). Media use in the middle east 2017: A seven-nation survey (Monograph). Qatar: Northwestern University in Qatar. [Google Scholar]

89. Araújo, C., Magno, G., Meira, Jr, W., Hartung, P., Doneda, D. (2017). Characterizing videos, audience and advertising in Youtube channels for kids. Germany, Springer. [Google Scholar]

90. Endestad, T., Heim, J., Kaare, B., Torgersen, L., Brandtzæg, P. B. (2011). Media user types among young children and social displacement. Nordicom Review, 32(1), 17–30. DOI 10.1515/nor-2017-0102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Ward, L., Harrison, K. (2005). The impact of media use on girls’ beliefs about gender roles, their bodies, and sexual relationships: A research synthesis. In: Cole, E., Henderson, J. (Eds.Featuring females: Feminist analyses of media, USA: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |