| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.019135

ARTICLE

The Kazdin Method for Developing and Changing Behavior of Children and Adolescents

Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 06517, USA

*Corresponding Author: Alan E. Kazdin. Email: alan.kazdin@yale.edu

Received: 05 September 2021; Accepted: 18 September 2021

Abstract: The Kazdin Method™ is a version of parent management training in which parents are trained to alter the behaviors of their children. The method draws on the principles and techniques of applied behavior analysis. The techniques focus on antecedents (what comes before the behavior), behavior (crafting the precise behaviors one wishes to develop), and consequences (usually praise to increase the likelihood that the desired behaviors will be performed again). The key focus is repeated practice in changing parent and child behaviors. The article traces the evolution of my use of parent training to treat severe aggressive and antisocial behavior among clinically referred samples and also to help parents with the routine challenges of child rearing. Research findings supporting the effectiveness of the techniques are highlighted. In addition, the article discusses issues and myths that may be of concern with the approach such as the exclusive focus on behavior, the extent to which the effects endure, and the use of consequences to change behavior. Resources are provide for parents and professionals for implementing the techniques and as well as for addressing topics of interest to parents in child and adolescent development.

Keywords: Kazdin method; changing parent; child behavior

In everyday life and in many settings such as the home, day-care centers, schools, clinics, businesses, and of course society at large there is a great interest in changing human behavior, whether of the persons who are served (e.g., children and adolescents, customers, citizens) or the people who oversee them (e.g., parents, teachers, employees, government officials). For example, we would like children to learn to negotiate the world and to engage in various activities that will help them in the short- and long-term (e.g., learning, building competencies, helping themselves and others). And we would like children, adolescents, and adults to engage in activities that sustain and enhance their mental and physical health, to follow laws, to help those who are less fortunate in some way, and to support the natural environment on which we all rely. The most common method of trying to change or influence behavior is to inform people, tell them about facts and latest scientific findings, give feedback about the benefits and positive consequences of various actions (e.g., eating a healthy diet, exercising) and the potential disadvantages about not engaging in those actions. These strategies occasionally change behavior, but as interventions go, they are relatively weak. By weak, I mean they may not effect many people and are not likely to develop enduring habits. They may be a step above New Year’s resolutions because they often have authoritative agencies, companies, or scientists, behind them or elicit others (e.g., movie stars, famous artists) to make the messages more salient. Any of these can work and in the context of advertising and selling products they often do. Yet, most of the changes in which we are interested have to do with building enduring habits or overcoming maladaptive behavior likely to impair functioning in some way. There is a great deal of research on how to change human behavior and in ways that develop enduring patterns.

The Kazdin-Method draws on, but did not invent, many of the effective procedures that can be used to change behavior and with a focus on children, adolescents, and their parents.1 There are many principles and techniques based on decades of scientific work in experimental (laboratory) and applied settings and serve as the basis for the method described here. This article highlights the path leading to development of the Kazdin Method, key techniques that are used to change behavior, and critical issues related to the approach. Also, the article ends with resources both for parents and professionals that elaborate the method in concrete ways so the techniques can be applied in the home. In addition, the resources include several articles on topics related child and adolescent development, child rearing, and mental health.

Beginning in graduate school and continuing throughout my career, I have been working in various applied settings in which the explicit task was to make demonstrable changes in behavior of the clients in ways that would make a palpable difference in their lives. In the initial setting, while a graduate student, I worked at a facility that served a wide age range of individuals (children through the elderly) with psychiatric disorders and intellectual disabilities. The director asked me to help change behaviors of adolescents and adults in the sheltered workshop part of the setting so they could be placed in the community. He knew I was interested in changing behavior but merely a graduate student interested in the topic. I knew little about the scientific underpinnings of my task. He told me to spend all the time needed to acquire the knowledge and then begin concretely with staff to make a difference in the behavior of the clients in ways that would help them procure jobs in the community. I began learning techniques of applied behavior analysis and the methods of evaluating interventions of individual cases. Applied behavior analysis refers to the application of techniques derived from operant conditioning and experimental research.2 After a few months of contacting many experts in the field, reading their papers, and beginning to understand the approach, I began interventions with individuals in the setting. With the staff and working with one client at a time, we were able to change behavior in many domains (e.g., excessive tantrums, negative comments, social skills, managing change and transitions, work performance).

As one illustration, I was asked to change the attitudes and behaviors of a 16-year old male, who constantly and seemingly randomly swore out loud, made abusive comments to the female staff, complained throughout the day about the work and setting, and had outbursts from what seemed to result from the slightest or no clear provocation. It would be wonderful to understand the underpinnings of these behaviors but of course that is no guarantee that one can then make the needed changes. Yet, absent the knowledge, could we change the behaviors and attitudes of that adolescent? In that case, we could by using procedures to develop the desired behaviors in place of those we wished to eliminate, a point to which I will return.

A local superintendent in the schools heard of the work I was doing and asked me to work with several classroom teachers in one of the elementary schools under his charge. The school included kindergarten through 6th grade and students ages 5–11). The task was to work with the teachers to change problem child behaviors and improve on-task and academic performance. The first request for my help was a dramatic introduction to the challenges. I was asked to give top priority to the case of a “hyperactive boy” who was extremely disruptive. I met separately with the teacher for a little background just to get oriented to the task. She noted that the child was a brilliant 10-year old boy (tested at an extremely high IQ level), who walked on top of all the desks (in a U-shaped arrangement in class) during a lesson, stepped on the papers and classwork of his classmates in the process, spoke very loudly while he was walking as the teacher was trying to present a lesson, and then occasionally went to the front of the room, got down from the desks, and fondled the teacher’s breasts. I was rather skeptical, so I observed by sitting in the back of the room for a couple of days. Everything was true exactly as stated.

What could possibly be done? Behavior analysis provides some leads, and I began there with the help of the teacher. We began by providing individual attention and teacher praise whenever he was not doing any of the objectional behaviors I listed, even if this was for a few moments (a technique referred to as differential reinforcement of other behavior). After a few days, sitting in his seat and speaking appropriately (not talking loudly) increased noticeably but was hardly adequate. Now the teacher provided praise when the child was working on the class assignments (differential reinforcement of alternative behavior) and for going for longer periods once the class began without any disruptive behavior (differential reinforcement of low rates of behavior). Any disruptive behavior would include any of those activities I mentioned previously including not going to the front of the room where he had physical contact with the teacher.3

In the beginning, I sat at the back of the room and signaled the teacher when to go over to the child to praise him, but soon I just observed and let the teacher work on her own. She and I met after class to evaluate progress, decide if it was time to make any changes in the intervention, and if so what changes to make. Through no special magic but systematic use the techniques, we were able to get the boy back in his seat, learning the lessons, and speaking out only when appropriate in response to queries the teacher posed to the class. The original sequence of problem behaviors and its individual components were no longer evident. This all involved shaping and moving from very small changes to larger ones and focusing on the behaviors to be developed (sitting in his seat rather than walking on desks, not blurting out, not approaching or touching the teacher). Beyond this one child, I worked in several classrooms helping to design and implement interventions for individual students as well as for entire classrooms.

After this project, I finished graduate school and soon moved to a faculty position at a university (The Pennsylvania State University, Pennsylvania, USA). I continued to work in schools in regular as well as special education classrooms with the goal of improving classroom behaviors, social skills, and academic performance. Over a period of 10 years, I conducted studies to improve the impact of behavior-change techniques as well as to better understand how they worked.

2.2 Psychiatric Inpatient Service

After 10 years, I moved from an academic psychology department to a psychiatry department at a medical school (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pennsylvania, USA). Here again the challenge was to change behavior but with more complexities than before. I was placed in charge of a psychiatric inpatient service for children, ages 5–12 (Children’s Psychiatric Intensive Care Service). As the name suggests, children were admitted because of severe clinical dysfunction and often were brought to the hospital by ambulance or police and on a gurney. The main clinical problem leading to admission was extreme aggressive and antisocial behavior. The psychiatric diagnosis is Conduct Disorder, although most of the children referred for hospitalization met criteria for multiple psychiatric disorders. Among the key symptoms are extremes of aggression, property destruction, theft, vandalism, fire setting, running away, cruelty to other humans and animals, and in general regularly breaking social norms and rules.

As an illustration, my first case was a 12-year old boy who stabbed his father (life-threatening injury) while the father was raping his mother, who was screaming for help. The boy grabbed a kitchen knife, ran into the bedroom, sliced the back of the father’s leg from just a little below the back of the knee to the bottom of the tendon near the ankle, and ran out of the house. The boy then stole a car and crashed it when the police finally caught up with him. The boy had a long string of aggressive and violent acts at home and at school but this one led to immediate hospitalization at the service I was directing. This was my first case, a challenge to say the least but not even among the most extreme cases that entered the service.

As I took this position, the chairman of the department of psychiatry noted that no one knew how to effectively treat children with patterns of extreme aggressive and antisocial behavior, and it would be very important to commit my efforts and resources of the setting to that problem. The locked inpatient service included staff representing multiple disciplines (child psychiatry, psychology, social work, nursing, rehabilitation, and education). On the service, we tried many reasonable treatment options (e.g., various medications, traditional individual and group therapies, social skills training, and a structured milieu) and occasionally even allowed parents to try options they viewed as reasonable (e.g., exorcism). We decided to develop and evaluate treatments for the children. We began by using applied behavior analysis interventions as a basis for training parents how to alter the problematic behaviors of their children. The parents served the therapists and our task during the sessions was to train them in very specific skills they would then apply at home. In some sessions, we brought the child in as the parents practiced the skills. The challenge was to develop very special skills in the parents and to build these as firmly planted and concrete behaviors parents could and would actually do. The treatment began while the child was hospitalized and then continued briefly when the child was returned to his or her home or another institution.4 Eventually, I moved from the inpatient service but in the same department and began an outpatient clinic. We treated children with the same problems but hospitalization was much less of a viable option (in part for more limited insurance and funding for children to stay in inpatient settings).

After 10 years at the prior setting, I moved to Yale University (Connecticut, USA) and replicated the outpatient clinic under the new name, The Yale Child Conduct Clinic, where we continued to treat severe aggressive and antisocial behavior among children and young adolescents. The plan was to work with children 5–12 in keeping with prior work, but the clinical demand required to expansion (ages 2–15). This work continued the focus on clinically referred children and their families. As before, these children and young adolescents engaged in a range of aggressive and antisocial behaviors and with multiple psychiatric diagnoses.5

After several years of work, parents began contacting us with a request for help with the challenges of everyday childrearing. This was fostered in part by the fact that I had been doing media work (e.g., television, radio, online and print magazines) each week for several years and this gave visibility to the clinical service that I had not anticipated. Eventually we received comments from parents in the community noting the following points and sentiment, “You can stop children from fighting, fire setting, and running away from home but can you get my child to eat vegetables, to practice his musical instrument, or get my teen-age daughter to not swear at me when I merely ask her how her day was at school?” Parents began contacting us from all over the world asking for help with requests to focus on such problems as children not complying with parental requests, showing disrespect, finicky eating, not doing homework, not engaging in self-care (bathing, brushing teeth, proper toileting, getting dressed), teasing and being mean to a sibling or pet, not going to bed on time, not cleaning up after oneself, and many others. We expanded our clinical service and continued to provide treatment to children with severe aggressive and antisocial behavior but also to provide parent training to families who wanted help with the challenges of everyday child rearing. During this period and with the request of a parent, we changed our name of our service so it did not imply that anyone attending was there for conduct problems and psychiatric impairment. We became the Yale Parenting Center; we continued our service to provide treatment to children and young adolescents referred for severe aggressive and antisocial behavior. We now more formally added training of parents to handle the routine challenges of childrearing. The intervention techniques were the same, as described later, but the duration and intensity of the sessions were reduced for the families focusing on the more circumscribed behaviors and childrearing challenges.

Our work with clinically referred children was supported by grants. In contrast, our work with parents for the routine challenges of child rearing had no outside funding. We could not charge families for the actual high costs of providing the service (e.g., staff time, overhead) or keep up with the demand. Indeed, we were providing sessions individually (on screen) to parents all over the world (e.g., Australia, Belgium, Canada, Luxembourg, Peru). Because of the demand and absence of funding to hire additional staff, we had to end service for these latter parents all the while continuing our work with clinically referred cases. To help parents with routine challenges, we prepared several resources (noted at the end of this article) including a free online course that demonstrated the techniques we use and how to apply them to children and adolescents in the home.

3 Changing Behavior: Key Concepts and Techniques

The key techniques of parent management training are based on applied behavior analysis and research that derived from basic human and nonhuman animal laboratory research. The research has generated principles and techniques have been elaborated elsewhere (e.g., Cooper et al. [5], Kazdin [3]). I highlight here core concepts that convey the approach.

Perhaps the most central concept of the approach is repeated practice of the desired behaviors. The goal is to develop behaviors by having individuals, whether children or adults, repeatedly engage in the desired behavior. In everyday life, we know that practice is important in developing behavior. If you, the reader, play a musical instrument, you can appreciate this point from your experience. Beyond our everyday experience, we know that changes in the brain develop along with the ability to play a musical instrument and that the degree of change is based on the amount of practice and experience (e.g., Janzen et al. [6], Proverbio et al. [7]). In changing parent and child behavior, practice is no less important and that is our focus in the treatment sessions.

For example, we train the parents to execute the behavior-change techniques in individual sessions separately with each family. To accomplish this, we focus on a very specific behavior (e.g., how to deliver praise) and practice this in the session. We teach parents each skill by modeling the behavior in the session, having the parent then do the technique, and going back and forth in this way to shape, craft the skill, and engage in repeated practice until the parent can carry out the technique reliably well. As part of this, we practice precisely how the parent will carry out the technique in the home, as individualized to their child and the child behaviors we are trying to alter. Within the sessions, the therapist and parent take turns playing the role of the child. We make application of the skill increasingly challenging by pretending to be a recalcitrant child, modeling how to respond to that, having the parent practice, and so on. The therapist is actively involved in praising the parent and using special antecedents to prompt improved behavior. Parents actually find the sessions very enjoyable. For the first time in their treatment experiences, they are not being negatively evaluated (as the cause of the child’s problem), have concrete procedures to use in the home, and can see some effects of the procedures relatively quickly.

The parent’s task is to implement what we practice so they can change child behavior at home. We begin by having parents change simple behaviors at home (e.g., having the child do some simple chore or help with a cleanup task). The initial goal is to ensure parents can carry out the techniques and do so relatively well. We move to more complex and then clinically relevant behaviors of the child. The behavior-change techniques that we use to develop parent behaviors are similar to those the parent will implement at home to develop the behaviors of their children. Repeated practice of the behaviors to be learned is critical in both contexts.

The techniques to change behavior can be grouped into three categories:

• Antecedents (what comes before behavior),

• Behavior (how the behavior is crafted to achieve the goal), and

• Consequences (that which follows behavior).

Antecedents can include the facial expressions, tone of voice, the way in which a request is made, physical guidance, gestures, modeling the behavior, verbal instructions, providing choice or options as part of the request, and offering a challenge. Each of these can greatly increase the likelihood of getting the individual, parent or child, to engage in the behavior and to engage in the behavior on more than just one occasion. The antecedents are absolutely critical and a change in any of these (e.g., facial expression, tone of voice) can make a huge difference in whether a given behavior is likely or unlikely to occur. For example, whether a child complies is not merely some characteristic within the child, but also in what is being asked and how it is being asked. A huge part of parent training focuses on how to use antecedents to attain the desired behavior. Again, we do not merely instruct or tell parents about antecedents. Rather we practice and over practice the skills in their use in the sessions.

Behavior consists of what is done to develop the terminal goal, that is, what the final behavior is that one is seeking. Shaping is gradually developing the behavior toward some end. Shaping begins with what the parent or child can do, and increasingly develops the behavior from that. For example, parents will need to administer praise in a special way, as noted below. We begin with what the parent can do and gradually shape the terminal goal, namely, delivering praise in a way that is likely to optimally effective. Sometimes the behavior we wish to change is not evident and cannot be easily shaped from a starting point. For example, many of the children we see do not comply with parental requests in everyday life. If the behavior of the child does not occur, one can practice this in role-play and simulated conditions at home. We make a game-like situation out of this in which the child engages in the desired behavior in contrived situations. Very soon the desired behavior transfers to everyday situations and can be praised there.

Consequences consist of what follows behavior. Consequences are important because they increase the likelihood that the behavior will recur. Parental praise is the primary consequence on which we rely, but the praise must be delivered in a very special way to be effective. For example, for young children, to be optimally effective praise by the parent ought to be effusive, to state exactly what is being praised, and followed with some nonverbal affectionate or approving gesture (e.g., gentle touch on the head or shoulder as dictated by family or cultural practice). This praise has to be rehearsed extensively in the sessions to shape and bring parents to the terminal goal. To help, we convey to parents there are two kinds of praise. That which they do in everyday life, and we encourage them to continue that, and that which is more strategic when they wish to change and develop behavior. It is this latter praise that we are developing.

One question might be whether praise loses its effects over time perhaps because of the equivalent of satiation. Actually, praise is a conditioned reinforcer, meaning that is associated with many other rewards, and tends not to lose its effects the way many other reinforcers might (e.g., activities, food). In addition, the special praise is not randomly given out multiple times. Rather it is provided only after the desired behavior or approximation of it. There is no intention in using this praise sparingly. However, it is not something merely blurted out often. Finally, like most of us at all ages, positive recognition for what we do does not seem to be something of which we tire. And the same with children. The praise for their specific behavior yields the same side effects as we have when our efforts are recognized, joy and pleasure.

Praise is the consequence on which we heavily rely but comments are warranted on other options. We tend to avoid the use of large rewards that parents often propose. Large regards (a trip to the movies), tangibles (a new smart phone, new video game), money, and food are not needed as consequences and often have other problems. For example, the delay after the behavior is critically important; behavior has to be rewarded immediately for maximum benefits. Praise makes that relatively easy. In contrast, large rewards and special events are not frequently and nimbly delivered and we tend to avoid them.

Sometimes tokens or points are used along with praise. Token reinforcement refers to things like starts, tickets, points, and the like that are earned by the child and used to buy other rewards (e.g., trinkets, extra bedtime, more time on the computer, and here larger rewards can be purchased). The system includes desired behaviors that are given tokens (point values for their completion) and a menu of backup rewards (with point costs) for which they can be exchanged, a system referred to as a token economy. Token economies have been applied to a wide age range (toddlers through older adults), in schools at all levels (e.g., preschool, elementary and secondary schools, colleges and universities), for individuals with a diverse range of problems related to physical health, mental health, and intellectual disabilities), by various organizations (e.g., professional and amateur athletic teams, the military, small and large businesses), and for a variety of behaviors in the community (e.g., conservation, littering, safe driving) (e.g., Hackenberg [8], Ivy et al. [9], Kazdin [10]). It would be difficult to imagine any psychological or psychosocial intervention that has been as widely and effectively implemented across samples, settings, and target foci as has the token economy and that has an evidence base!

With that buildup, it is important to know that we do not rely heavily on token reinforcement or token economies to change behavior. The system is usually not needed and praise delivered in the manner I have noted often is sufficient. Occasionally, we have used token systems to help parents rather than the children. That is, if parents are to deliver concrete rewards (e.g., points, stars), they are more likely to administer the praise that would go with that. Token economies can be very helpful but they introduce complexities (devising a system, ensuing backup rewards are suitable and are earned), that we usually do not need to add. That said, it is a useful technique if praise is not working sufficiently or the parent is having difficulty in implementing the praise.

To change child or parent behavior, antecedents, behaviors, and consequences are essential and used together. Each of these can be used to initiate the behavior, to obtain repeated occurrences, and to lock it into the child’s repertoire. After the behavior becomes stable, the intervention can be eliminated. As an example, we are frequently called on to eliminate explosive tantrums. These might include crying and shouting for 30 or more minutes, hitting the parent, breaking things, and refusing to do anything. We can craft this to a less intense tantrum in a fun simulation game with the child where the parent praises “good tantrums” after pretending to not allow the child to do something. Antecedents are absolutely critical to set the stage and clarify what is being asked. After an initial practice, another antecedent might be given, such as the parent saying, while smiling and in a playful, mischievous voice, “I’ll bet you cannot do the good tantrum twice in a row. No 5-year-old can do that”. Of course, with that challenge, well-rehearsed in the treatment session, the child’s reaction is a huge smile and a confident statement that he can do it twice. The parent yields and they practice this again. This goes on with the game once a day if possible for a week or so. During this period, some of the tantrums outside of the game take on those characteristics of a good tantrum and they are praised there. In a 2–3 weeks usually, the tantrums are fine, tolerable, and infrequent. The intervention is ended, and the matter does not emerge again.

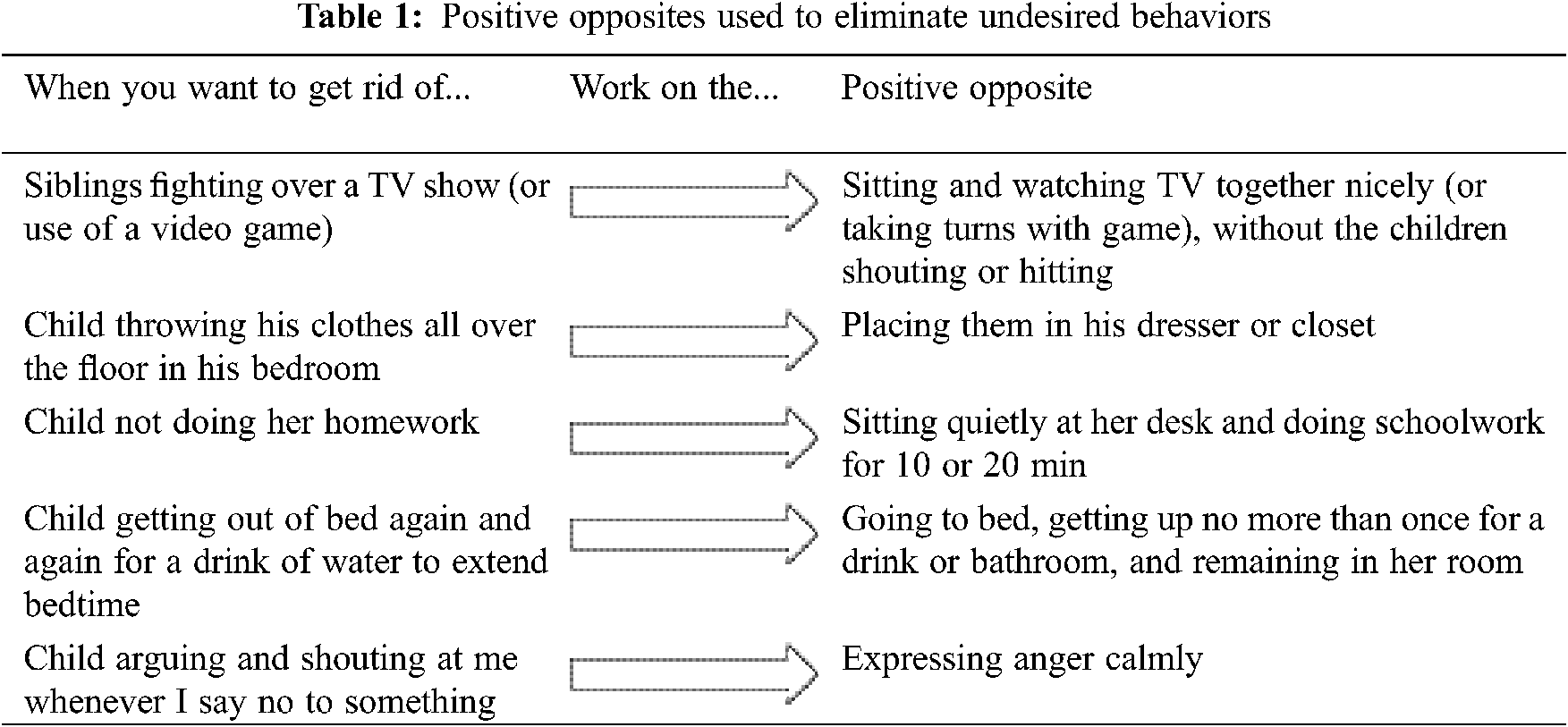

3.3 Reducing and Eliminating Undesired Behaviors

Another feature worth noting is how to eliminate behavior. Punishment is not very effective in eliminating undesired behavior and developing new behaviors. Momentarily one can suppress behavior with punishment (e.g., reprimand, shout) but the behavior is likely to re-emerge quickly, at the same level, and with no enduring effects beyond the moment. A cliché in parenting in the United States is the parent’s statement of frustration to the child, “If I have told you once I have told you a thousand times, never to [insert undesired behavior here]”. We know that repeated telling (nagging) is not likely to work with children, spouses, or partners. Punishment usually has the same effect, namely, little enduring impact or development of the desired behaviors.

We want to build habits and merely suppressing behavior for the moment does not do that. To reduce or eliminate undesirable behavior, we develop the desired behaviors. We refer to these desired behaviors as positive opposites. Table 1 provides some examples. If one wants to reduce or eliminate some behavior (left side of the table), the focus is on developing those positive opposite behaviors (right side of the table). Very mild punishment (e.g., brief time out, taking away a privilege for a brief period of a day) can be useful but the weight of the program comes from developing the positive opposite behavior. The range of techniques to develop the positive opposite involve those encompassed by the combined use of antecedents, behaviors, and consequences.

There are fairly sophisticated ways of developing positive opposites. They amount to praising the desired behaviors but there are options that vary in how this is done. I mentioned some of these options earlier with the focus of the child in the classroom who walked on the desks of other students during the class sessions. For example, if an undesired behavior occurs very often, one can praise the child at any time she is not engaging in that behavior (differential reinforcement of other behavior). That will increase the periods without the behavior. One can then praise behaviors that are incompatible with or are alternatives to the undesired behavior (different reinforcement if incompatible behavior). For example, if a child is shouting or speaking nastily to others, one offers praise for speaking in a lower tone of voice and speaking prosocially. If an undesired behavior occurs frequently, one can also praise periods of time that elapse without the behavior (differential reinforcement of low rates). Thus, if a child is aggressive in the classroom, one can begin the day by seeing if the child can last for 5 or 10 min without any aggressive behavior. Through shaping the time period can be extended to the full day or even multiple days in a row. These samples merely convey that there a range of techniques, only a few of which I can mention here (Kazdin [3]).

The vast majority of the techniques that comprise the Kazdin-Method are based on applied behavior analysis. Yet, three features distinguish our approach. First, we give great attention to antecedents. What can be done to increase the likelihood of getting the desired behavior in the first place? Modeling the behavior, directly assisting in any way necessary at first, and being positive in how the tasks is presented are among the main antecedents. We use “challenges” with young children and that is very useful in initiating the behavior and getting repetition of that same behavior.

Second, and related. We try to provide choices to children whenever possible. These are not choices that parents often use, which are better referred to as threats. Those threat-choices include doing something or facing some undesirable consequence. Choices we provide are two ways of doing some positive behavior. For example, the weather may be very cool so before going outside for a walk, we ask the child to wear the blue jacket or the brown sweater? The child has homework and we ask the child whether he wants to start with or without the parent for the first 10 min (for a child that is not doing homework). We rely on choice because that increases the likelihood of getting the desired behavior. Also, it is opposite from authoritative statements that parents are wont to make. Authoritative statements, sprinkled with a harsh tone, are likely to lead to reactance, a phenomenon that refers to a negative reaction and oppositional behavior.

Finally, we rely heavily on simulations. As I mentioned and illustrated before, there are times when the parent and child practice the desired behavior in a game-like situation. The key concept of the approach is repeated practice and that can begin in artificial role play situations. Simulation training is common in other facets of life (e.g., military training, commercial airline pilot training, training of surgeons). In these cases, training under artificial situations transfers over to everyday life and that is what we find as well with simulations. Once the behavior occurs in everyday life with the child, we can usually stop the simulation and rely on praise in those everyday situations.

4 Research Bases of the Techniques

I mentioned that the techniques we use have a basis in years of research in laboratory and applied settings. That is valuable to note but no guarantee that our techniques are effective in the context of our focus on children and adolescents with extremes of aggressive and antisocial behavior. For the past 35 years, we have been conducting studies (randomized controlled trials) of the treatment and have evaluated several facets of the child, parents, and contexts (e.g., stress) that influence therapeutic change (see Kazdin [4]. for a review). Our main findings indicate that parent management training:

• Reduces antisocial behavior and increases prosocial behavior of children at home and at school;

• Is effective with a range of severity of cases, as reflected in inpatient and outpatient samples who meet criteria for one or multiple psychiatric disorders;

• Leads to approximately 80 percent of the youth making large and important changes, as attested to by their parents;

• Produces changes that are maintained up to a final point at which we could follow them (2 years after treatment);

• Is associated with significant decreases in parental depression and stress at home and improved family relations; and

• Is equally effective whether delivered on-line or in person.

Apart from treatment outcome studies, we have evaluated many facets of treatment including the role of the therapeutic alliance, factors that predict therapeutic change, who drops out of treatment and why, and various characteristics of treatment delivery. The goal is to understand the treatment process as well as factors that might be mobilized to improved therapeutic change.

For example, generally the families we see in the context of our clinical referrals experience high levels of stress, often from difficult living situations, strained relationships with partners or family members, economic hardship, pending legal issues, few positive supports (families), and conflict with various social agencies. Our research has shown that stress in the life of the parents is associated with reduced therapeutic change among the children. After studying this, we devised an intervention to help with parent stress. In a randomized controlled trial showed that the effectiveness of parent management in altering child behavior improved if we also focused on parenting stress (Kazdin et al. [11]). As this study illustrated, there is much to understand to optimize the benefits of treatment.

I have only highlighted the research here to give greater attention to describing the method itself. Yet it is important to note, the approach is not one person (in this case me) with “the answer” to a clinical problem or to the challenges of childrearing. The parenting techniques are well studied scientifically and many researchers have evaluated variations of the intervention (for reviews see Baumann et al. [12], Colalillo et al. [13], Dedousis-Wallace et al. [14]). Beyond parents, the techniques have been applied very widely to many different populations, as I noted earlier in the discussion of the token economy. The most visible applications now are in relation to the treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder where variations of behavior analyses have been shown to have significant impact on children with the disorder (Yu et al. [15]). In any case, in the context of interventions for clinically severe aggressive and antisocial behavior, the primary focus of our work, parent management training clearly qualifies as an evidence-based treatment. There have been many evaluations of the procedure with less severe cases and to help parents with the routine challenges of daily life.

Several important points are worth noting to place the intervention in context. First and foremost is the point that applies to any psychological, educational, medical, dietary, and other intervention, namely, the intervention does not work with everyone. What makes parent management training worth trying is the derivation of the techniques from both basic laboratory and applied research and direct evidence in the context of parenting. The basic and applied research means that the procedures are reasonably well understood. For example, we know how to administer consequences so they change behavior and from that we know that if the consequences are not administered in that way the intervention is not likely to be effective. Even so, effective treatments applied to most people is no guarantee that in any individual case the desired effects will be obtained.

Second, the techniques I have mentioned convey what we do and what procedures we use. The what is very different from the how. That is, the way in which the techniques are implemented make a huge difference. For example, the same statements or acts of a parent can greatly influence what the child does based on how those statements are delivered. Parents often tell us the equivalent of, “I use praise already in the home”. “Or I use time out from reinforcement”. “And trust me they do not work”. The parents are correct, but with changes in the what they do and even larger changes in how they do it the impact on child behavior can be dramatic. How the procedures are implemented are difficult to convey in words but are readily demonstrated (see online course mentioned below).

Third, in our clinical applications, we have focused on families living in very difficult circumstances. These include psychiatric impairment among the parents, use of illicit drugs, engaging in prostitution to support the family, poverty, high levels of stress, contacts with the law over their own behavior, and difficult interactions outside of the home (e.g., with school personnel, social agencies). By the time a family has come to us, usually they have traversed a small handful of other treatments that were not very helpful. Thus, the clinical challenges in applying the treatment extend beyond changing child behavior. One begins with what a parent or parents can do and develops the behavior from there. I have not outlined the range of obstacles in applying the intervention; there are many but they are often surmountable.

Fourth, sometimes the approach is mischaracterized as rewarding behavior or throwing consequences at behavior. The approach consists of the integration of antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. Consequences are involved but they are only a part of the method. If a program were only based on consequences, we would expect it to fail badly. Calling parent management training or conceiving the method as reward programs is not merely an oversimplification but inaccurate. As an analogy, consider the medical procedures of surgery as including three parts: making an incision, cutting or removing what is needed, sewing or sealing up the skin. One would not focus on one part and say that surgery means sewing up the skin. Parent management is not merely providing consequences. Recall that the main goal is repeated practice of the desired behavior. Multiple techniques are used to achieve that; consequences is one of them.

Fifth, the techniques have been shown to develop behavior, but this leaves unclear what happens once the techniques are discontinued. Are the behaviors maintained? Once the behaviors are established, they can be maintained. To begin, there are a number of specific techniques that are designed specifically to maintain behavior once the behavior has been developed (Kazdin [3]). Some of these amount to gradually fading the procedures so they are administered on fewer occasions, less regularly, and for larger segments of behavior. In fact, in the day-to-day, we have not had to rely on those techniques very much. The reason is that after the behavior is developed, the program tends to fade gradually as the need is reduced and the behavior is maintained. For example, after developing a reasonable instead of explosive tantrum or better compliance with requests, terminating the specific program does lead to loss of these gains. The program develops habits. Indeed, one reason punishment plays such a minimal role is that behavior that is punished usually returns really quickly and the desired behaviors have not been developed.

Finally, one concern with the approach is that the focus is exclusively on behavior. Indeed, children referred to us clinically as well as the children whose parents wish help with the routine challenges of child rearing typically have an agenda that focuses on changing specific behaviors. Yet, many psychological problems involve emotions, cognitions, and behaviors. Are we ignoring nonbehavioral components? Not at all. For example, one of the evidence-based treatments for anxiety is graduated exposure to the situation or circumstances that provoke anxiety (e.g., strong emotions, cognitions including maladaptive self-statements, and avoidance behavior). In our program, we have shaped approach behavior as a form of graduated exposure and as a way of overcoming fear in children. The effects are to alter how the children feel, think, and behave, as demonstrated by their reports and the activities in which they can eventually engage.

More generally, psychological interventions are rarely surgical and able to only affect behavior. Among children with extremes of aggressive and antisocial behavior, improving behavior often is the primary goal but even there one changes many other facets of functioning. Individuals whose behavior is more adaptive enter into more positive social contexts of everyday life and show less disability. The increased socialization alone improves functioning in multiple domains, well beyond the concrete behaviors that guided our focus. Also, in our own work, when we improve child behavior comments from parents go way beyond mere changes in behavior (e.g., “you made me love my child again,” or “our home is a happier place without the stress of my child’s horrible behavior”). Comments from teachers also go well beyond merely noting changes in concrete behaviors (e.g., the child has become a much friendlier and nicer person”). I also mentioned earlier that when we change child behavior in the home, parent depression and stress in the home decline and family relationships improve, all documented in our trials. In short, improving behaviors often has rather broad consequences for individuals and those around them.

Rather than a research review or a scientific article, I have highlighted the approach we have used both with clinically referred cases with diagnosable mental disorders and with children functioning well but whose parents would like help with the routine challenges of child rearing. I began the article noting the challenges presented to me professionally in different contexts and settings in which the goal was to develop behaviors to improve client functioning in everyday life. I turned to applied behavior analysis very early in my career because it provided two important components: 1) a concrete set of techniques that had been well studied in basic human and nonhuman animal research and in applied settings, and 2) a methodology for evaluating whether the change had occurred in the individual. I have not highlighted the evaluation procedures, but they include ways of determining if change is occurring and whether more, different, or better techniques are needed to help the client, all while the intervention is in effect (see Kazdin [16]).

There is no one theory, approach, or set of techniques that will provide answers or meet the many challenges we have in clinical, educational, and other areas of applied work. There are many solutions and strategies, but our obligation clinically is to draw on the evidence whenever possible, implement the techniques faithfully, and evaluate what we are doing. There is no guarantee that even an evidence-based intervention will be effective for any given individual. Consequently, some evaluation is needed to determine whether the change is occurring and at the level that is needed.

The challenges in applied settings are enormous. There are many people suffering and few resources to provide care, let alone effective care (Kazdin [17]). Once one is confronted with the individual case with disability and problem domains that impair performance, where does one begin? Diagnosis often is the first answer and that certainly seems reasonable. We definitely want to know the range of mental and physical conditions that might be present. Next, understanding the context (e.g., history, family situation, resources, strengths of the client) is also part of the initial step and that too is obviously important. Where the system breaks down often is in intervening and showing that the intervention makes a difference in the life of the client. Our focus has emphasized this later goal, guided by the question: Can we improve the behavior of children and adolescents having significant problems in their everyday lives? Our research and the research of many others have shown this goal can be achieved. Invariably more needs to be learned. Yet, even with what we know now we can help many families. The challenge is to disseminate the techniques—not just information about the techniques, but efforts to help develop the skills so they can be used in everyday settings. Resources we have provided, noted below, are one small step in this direction.

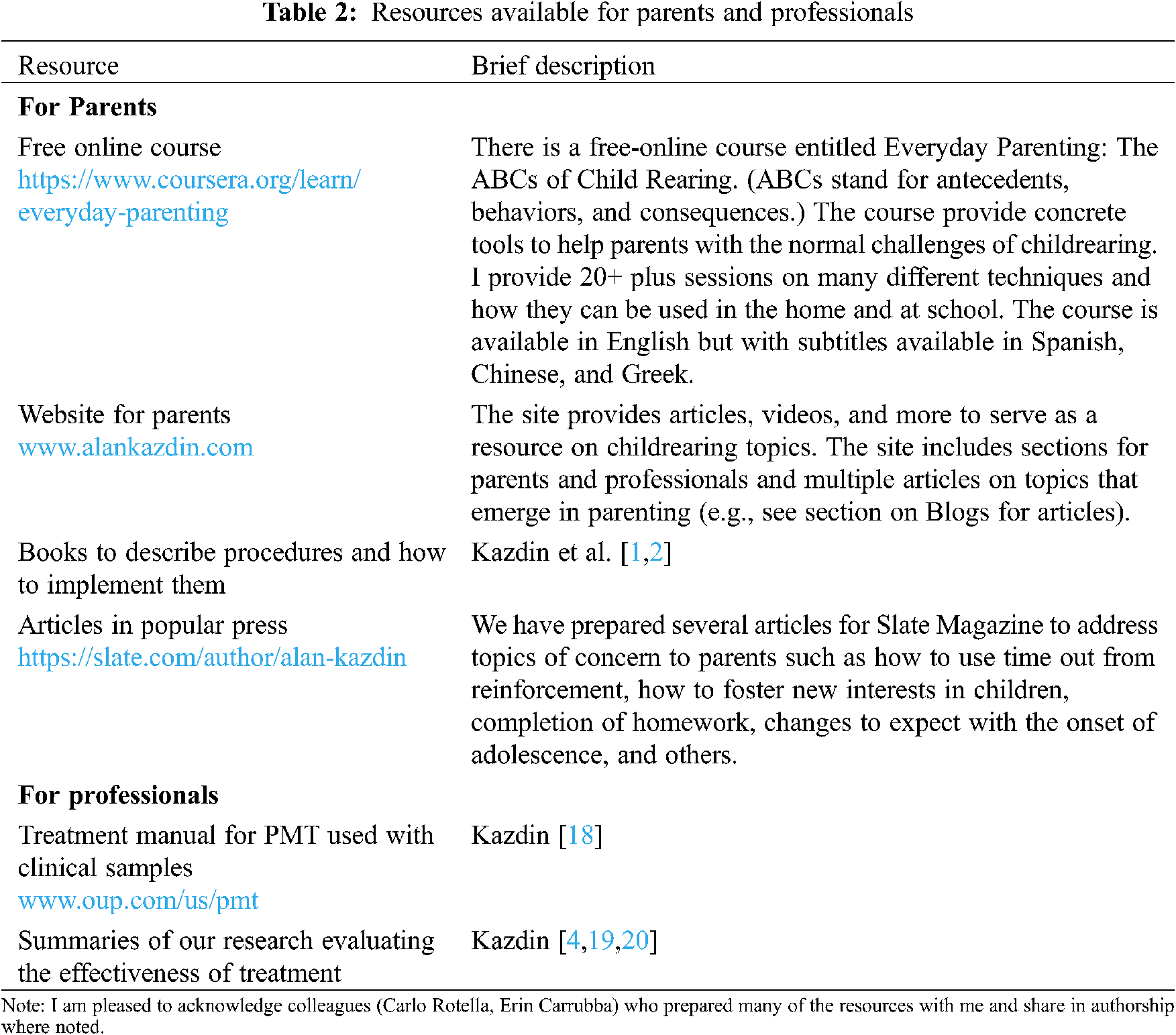

7 Resources for Parents and Professionals

I mentioned that we were unable to meet the demand for services. This was true for clinically referred cases but even more so for families who wanted help with the routine challenges of child rearing. Consequently, we prepared many materials designed to be of direct and practical use to parents. Also, there was interest professionally in providing details about our treatment. We prepared a book describing the treatment and what is done on a session-by-session basis with the parents. Table 2 lists resources for parents and professionals who deliver mental health services.

1The Kazdin-Method™ was first used in the context of two books for parents (Kazdin et al. [16,17]). The name is trademarked and refers to the compilation of techniques used to alter the behavior of children and adolescents. The intervention is more generically and properly labeled as parent management training, an intervention with many variations. Common among the variations is the use of principles and techniques derived from applied behavior analysis. Our variation includes some emphases and procedures that are different in details. I will refer to parent management training as the more generic intervention. The evidence for the effectiveness of parent management training includes but goes way beyond the research that my team has completed.

2Research on the experimental analysis of behavior and the applied analyses of behavior are published in many journals but primarily in the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior and the Journal of Applied Behavior Analyses. These journals convey the underpinnings of the techniques on which we rely and convey the very broad applicability of the procedures, respectively.

3Differential reinforcement includes a set of techniques in which different aspects of behavior receive consequences. These include many options: differential reinforcement of other behavior, of alternative behavior, of incompatible behavior, of low rates of responding, and of functionally equivalent behavior. The options are their use are described elsewhere (Kazdin [2]).

4For many children, there was no parent with whom we could work. The parent suffered from one or more psychiatric disorders or drug addiction, engaged in crimes such as prostitution and selling alcohol or drugs in the home, or were known or suspected to engage in physical or sexual abuse of the child. Occasionally we removed the child from the home and that of course precluded working with a parent who lived with the child. We needed an additional treatment that we could provide to the children without the involvement of the parent. To that end, we developed cognitive problem-solving skills training. This was an individual treatment with the child that trained strategies to approach interpersonal situations, especially those in which the child was having a problem. A key feature of the intervention is repeated practice of how to use the strategies and how to behave in role played situations and then in situations in everyday life. More information on the treatmxent and our evaluation of its effects are provided elsewhere (see Kazdin [8]).

5We wanted to restrict our focus to youth 12 and under in part because during middle and older adolescents, the problems often moved into use of illicit drugs, unprotected sex, living out of the home, problems with weapons, running away, and major theft.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this article.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares that he has no conflict of interest to report regarding this article.

1. Kazdin, A. E., Rotella, C. (2008). The Kazdin Method™ for parenting the defiant child: With no pills, no therapy, no contest of wills. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

2. Kazdin, A. E., Rotella, C. (2013). The everyday parenting toolkit: The Kazdin Method™ for easy, step-by-step lasting change for you and your child. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

3. Kazdin, A. E. (2013). Behavior modification in applied settings (7th ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

4. Kazdin, A. E. (2017). Parent management training and problem-solving skills training for child and adolescent conduct problems. In: Weisz, R., Kazdin, A. E. (Eds.Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents, 3rd ed., pp. 142–158. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

5. Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

6. Janzen, T. B., Thaut, M. H. (2019). Cerebral organization of music processing. In: Thaut, M. H., Hodges, D. A. (Eds.The Oxford handbook of music and the brain, pp. 89–121. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

7. Proverbio, A. M., Attardo, L., Cozzi, M., Zani, A. (2015). The effect of musical practice on gesture/sound pairing. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 376. DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hackenberg, T. D. (2018). Token reinforcement: Translational research and application. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51(2), 393–435. DOI 10.1002/jaba.439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ivy, J. W., Meindl, J. N., Overley, E., Robson, K. M. (2017). Token economy: A systematic review of procedural descriptions. Behavior Modification, 41(5), 708–737. DOI 10.1177/0145445517699559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kazdin, A. E. (1977). The token economy: A review and evaluation. New York: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

11. Kazdin, A. E., Whitley, M. K. (2003). Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 504–515. DOI 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Baumann, A. A., Powell, B. J., Kohl, P. L., Tabak, R. G., Penalba, V. et al. (2015). Cultural adaptation and implementation of evidence-based parent-training: A systematic review and critique of guiding evidence. Children and Youth Services Review, 53, 113–120. DOI 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Colalillo, S., Johnston, C. (2016). Parenting cognition and affective outcomes following parent management training: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(3), 216–235. DOI 10.1007/s10567-016-0208-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Dedousis-Wallace, A., Drysdale, S. A., McAloon, J., Ollendick, T. H. (2021). Parental and familial predictors and moderators of parent management treatment programs for conduct problems in youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24(1), 92–119. DOI 10.1007/s10567-020-00330-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yu, Q., Li, E., Li, L., Liang, W. (2020). Efficacy of interventions based on applied behavior analysis for autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Investigation, 17(5), 432–443. DOI 10.30773/pi.2019.0229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kazdin, A. E. (2021). Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

17. Kazdin, A. E. (2018). Innovations in psychosocial interventions and their delivery: leveraging cutting-edge science to improve the world’s mental health. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

18. Kazdin, A. E. (2009). Parent management training: Treatment for oppositional, aggressive, and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

19. Kazdin, A. E. (2011). Yale Parenting Center and Child Conduct Clinic. In: Norcross, J. C., VandenBos, G. R., Freedheim, D. K. (Eds.History of psychotherapy: Continuity and change, 2nd ed., pp. 363–369. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

20. Kazdin, A. E. (2018). Developing treatments for antisocial behavior among children: Controlled trials and uncontrolled tribulations. Perspectives in Psychological Science, 13, 634–650. DOI 10.1177/1745691618767880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |