| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.016199

ARTICLE

Perception of Student Life as Promoting Mental Health and Well-Being. A Study of First-Year Students in a Norwegian University

1Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Gjøvik, 2802, Norway

2University Health Care Research Center, Faculty of Medicin and Health, Örebro University, Örebro, SE-701 85, Sweden

*Corresponding Author: Anne Skoglund. Email: anne.skoglund@ntnu.no

Received: 17 February 2021; Accepted: 05 May 2021

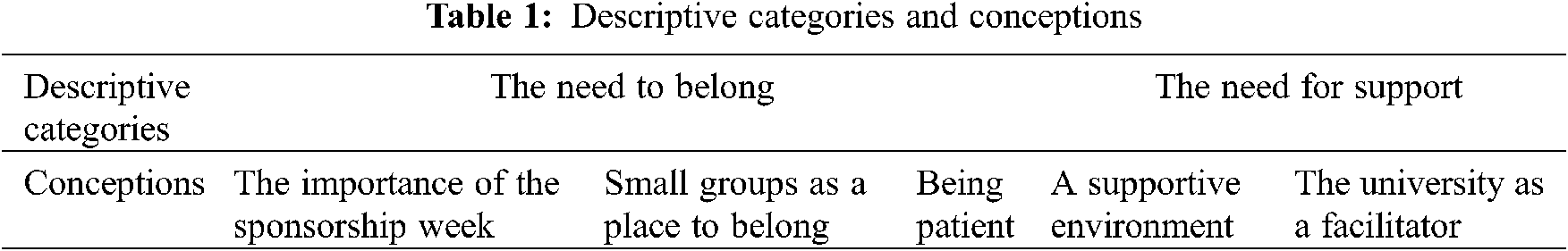

Abstract: In Norway, 300,000 people attend higher education. Elsewhere in Europe, student numbers are also high. In Great Britain, 1.9 million people attended higher education in the academic year 2018–2019. This is a substantial part of the population, and the mental health and well-being of students are of prime importance. The first year as a university student is a transitional period characterized by significant changes and constitutes an essential fundament for students in their student life and later. An increasing number of students report having mental health problems to various degrees. Identifying the variety of perceptions of what may promote mental health and well-being is therefore of importance. This study aims to explore whether first year students in higher education perceive student life as promoting their mental health and well-being. Twenty students were interviewed (n = 20). Phenomenographic analysis was used to reveal variation in the students’ perceptions. Two descriptive categories were constructed, “The need to belong” and “The need for support,” with five conceptions: the importance of the sponsorship week, small groups as a place to belong, being patient, a supportive environment and the university as a facilitator. How a sense of belonging and a sense of support was achieved varied among the participants, and the solution for how to achieve this lies in the students themselves, the way the university organizes the programmes and how the students are met by the administration, lecturers and fellow students.

Keywords: Mental health; students; university; well-being

Attending university is a time of transition for many students [1–3]. Both moving away from the parental home and transitioning from childhood to adulthood are key transitioning points in life, when students must learn to balance demands from family, work, and study life. Being a student is also about developing independence and learning life skills, and a period when students mature in their personal development. In addition, it is a crucial time to develop and prepare for their adult life and future roles in communities, workplaces and society [4,5]. According to Dooris [6], the university is fundamental not only in educating students, but also in stimulating their social and personal development. This development impacts on both their lives as students and their future.

Worldwide, the number of people enrolled in higher education has increased dramatically over the last decades. Schofer and Meyer estimated in 2005 that one-fifth of the cohort of college age people was enrolled in higher education [7]. In Great Britain, 1.9 out of 55 million British citizens were attending higher education in the period 2018–2019 [8]. In 2018, nearly 300 000 people in Norway were higher education students, and more than 35% of those between 19 and 24 were attending higher education [9]. Most students are content and satisfied with their student life even in this demanding time of change and new responsibilities. However, despite their excitement and expectations when starting a new life, both international studies [10–13] and the Norwegian Students’ SHoT study, a survey of the health and well-being of university students, show that a significant number of students report having mental health problems [14].

Contributors to mental health and well-being among students

Attention to students’ mental health needs has increased in the last decades. Evidence indicates that whole-setting approaches are more successful than one-off activities [5]. There has been a shift from focusing on student-related guidance in single case interventions in respect of drug use and mental health issues to an interest in a more holistic whole-university approach.

There may be several contributors to higher education students’ mental health. Usher finds that mental health policies need to be implemented within three main domains to ensure a holistic approach: personal, university and home [15]. Measures such as commitment to activities [16], mentorship, lunch buddy programmes, organizational efforts from both the universities and the students’ welfare organization may promote mental health. Architecture that supports social activities is another way of promoting students’ mental health, and there is evidence that targeted programmes also have a positive effect [10,17]. According to Ridner et al. [18], interventions that improve sleep quality are most beneficial in promoting college students’ well-being. Conley, Durlak et al. [3] found that skills-oriented, supervised, class-conducted programmes seem to be the most effective.

Despite this, database searches in Ovid Medline, Psychinfo, Eric and Embase on students, universities and mental health promotion, report few findings on how students experience student life as a contributor to mental health and well-being. In addition, intervention studies [3,17,19] and quantitative studies [13,18,20–22] are dominant in research on students’ mental health and health promotion, and there are few qualitative studies. This suggests a knowledge gap and a need to explore the qualitatively different ways students in higher education perceive their student life in a mental health-promoting perspective. Exploring variations in the students’ perception on contributors to better mental health and well-being may broaden the perspective and provide a more solid basis for better facilitation of a mentally healthy student life. Describing the variation in how the phenomenon is perceived may contribute to a broader perspective.

The aim of this study was to explore how first year students in higher education perceive student life as promoting mental health and well-being.

This study employed an exploratory qualitative research design using a phenomenographic approach. Phenomenography seeks to describe the variety of ways people experience or understand a phenomenon [23]. The phenomenon discussed in this study is what promotes mental well-being in students at a Norwegian university.

Phenomenography divides research into research focusing on first-order or second-order perspectives. The first-order perspective describes how something really is, while the second-order perspective describes how people experience or perceive the phenomenon. In this study, the focus is on the second-order perspective and how students perceive student life as promoting mental health and well-being.

2.1 Participants and Recruitment

The participants were recruited from a university in Norway with approximately 45,000 students. Inclusion criteria were that the participants had moved to the city for studies and that they were first year students. The recruitment sessions took place at three different campuses. The first author informed and asked students to participate at the end of lectures. Those interested signed up for further information by email. A total of 44 students wanted to participate. Out of these, 22 participants were strategically selected. Variation was assured by selecting approximately the same number of students aged 19–28 from each of the three study programmes. More female than male students wanted to participate, which gave a selection of approximately 1/3 male and 2/3 female participants. Seven participants studied STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), six studied medicine and seven studied psychology, either as a one-year study programme or a bachelor’s degree.

The interviews took place at the participants’ campus. The duration of the interviews ranged from 34 to 60 min, with a median duration of approximately 45 min. The first author conducted the interviews.

To create a friendly and comfortable atmosphere, the interviews started off with the first author presenting the study and reminding the participant about the research question: How do first year students in higher education perceive student life as promoting mental health and well-being?

The initial question was: ‘Can you describe your student life with focus on how you perceive it as promoting mental health and well-being?’

Follow up questions were: ‘Can you describe this in more detail?’ ‘Can you explain this?’ ‘Tell me more about that?’ ‘Is it always this way?’ The topics of mental health and well-being were raised if the participants had not described them unprompted.

The study was conducted in accordance with the research ethics guidelines of the Norwegian National Research Ethics Committee [24]. The participants were given an information letter about the project, the first author’s background and prior research, storage of data, anonymity, who to contact in case of questions etc. This was repeated orally before the interview started. Furthermore, they were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time, and that their data would be deleted. Consent was voluntary, explicit, and informed. The data collection was approved by the Data Protection Officer (NSD reference 873991). The interviews were taped, coded, and stored in accordance with research ethics regulations.

The data were analyzed using Dahlgren and Fallsberg’s sequence of activities in analyzing phenomenographic studies [25]. The seven steps of the phenomenographic process are described as: 1) familiarization–interviews were read through, mainly by the first author, to gain an overview impression; 2) condensation–significant utterances that were representative for the dialogue were selected, and a “pool of meaning” was constructed using 597 utterances; 3) comparison–the selected utterances were compared in order to find similarities and variation; 4) grouping or classification–utterances that appeared to be similar were grouped; 5) articulating–the essence of similarity within each group was described. Five conceptions were constructed based on differences and similarities in the student’s perceptions of the phenomena; 6) labelling–categories were named in order to emphasize their essence; and 7) contrastive comparison–the categories were compared in order to find similarities and differences, making them mutually exclusive. The conceptions were thoroughly investigated to see if any of the content was interchangeable. Moving utterances between different conceptions constituted an ongoing and continuous process as different meanings emerged. The steps are related, and it was necessary to go back and forth between the steps during the analysis process.

Nvivo was used as a tool to facilitate the analysis. The analysis process was performed primarily by the first author, with critical reflections from the other authors when reading and discussing the material.

The results show the variation in how the students perceived student life as promoting their mental health and well-being. Two descriptive categories were constructed: 1) The need to belong and 2) The need for support. The two categories consisted of five conceptions. This is described as the outcome space as shown in Table 1.

The outcome space describes how the phenomenon is related to its context (external horizon), and how the conceptions are related to each other [26]. The conceptions are logically related and the categories horizontally structured, as belonging is a prerequisite to achieve support.

The descriptive category the need to belong consists of three conceptions that participants perceive as influential to their mental health and well-being: “The importance of the sponsorship week”, “Small groups as a place to belong” and “Being patient”. Having someone to belong to in some way was regarded important, either socially or academically or both.

The importance of the sponsorship week is one of several conceptions that the participants describe that they perceive as important when starting as a student. Participating in the introductory weeks is considered crucial. It was during the sponsorship week many of the participants made friends, found someone to sit next to during lectures, and started the circle of making a network at the university. Some of the participants described the sponsorship group as a family while others found it unnecessary. Sponsorship activities, however, were perceived as excluding among students who did not consume alcohol, and some described the acquaintances they made as superficial. Sponsorship was used strategically to make networks, both personally and professionally. The positive aspects were described as follows: Even if you don’t drink, you should participate. For strategic reasons (Interview 20). One student underlined the negative aspects of not participating: I didn’t participate, so when the exams came up, I didn’t know anyone I could prepare with (Interview 10). A more neutral perception was also described: Many told me it would be hard to make friends if I didn’t participate, but that hasn’t been a problem (Interview 16).

“Girls’ day in technology” was highlighted as a great help to start with. A small group of girls who were about to start their science programmes met up and had their own sponsors to help them make friends the first days in the city, before the university term started. One girl described the day as helpful on her first day as a student: Girls’ day in technology, I recommend it to everybody. I wasn’t scared the first day, because I had someone to go along with (Interview 21).

The conception Small groups as a place to belong and a sense of belonging was expressed in many ways, and views on this were positive. Small groups promoted a sense of belonging among the students. They felt it easier to participate in discussions and had a lowered threshold for initiating dialogue. The students perceived small groups as a social and academic facilitator. Some of the small groups are led by senior students, and the threshold for asking questions and participating in the discussions was lower than in regular lectures. In addition, the sense of belonging and easy access to new acquaintances and friends were highlighted as important.

Conversational keys to acquire new acquaintances were described: When you’re divided into groups, you start talking about your studies. Then maybe you talk some more about other things, and through that comes a social thing (Interview 10).

A sense of belonging socially was highlighted. Belonging was expressed as crucial to being able to get through their education. This could refer to people they shared housing with, fellow students or someone who had the same academic interests or extracurricular interests. The housing situation was regarded as very important. However, one participant stressed that they did not want to mix private and academic life. It would be like living with a colleague (Interview 21). Others found that the housing situation contributed to a feeling of belonging: It’s like coming home to my family, kind of (Interview 1).

In some programmes, older students tutored groups of younger students and this was perceived as creating a closeness to their fellow students. Problem-based learning groups and other kinds of learning teams were also regarded as a socially safe arena to connect and make new friends. Tutorial groups led by more experienced students were described as ‘a great place to meet others, and it’s less scary to ask questions. I’m happy that we have them (Interview 21). Others regarded the student group as a mere workplace. You don’t get to know people well in these groups, you just work on your studies, so they don’t have to be my best friends (Interview 3).

The conception being patient was perceived by the participants as important. Networks and friends can be made both outside and after the sponsorship week, even though the sponsorship week is an important arena for many students in the introductory phase of their student life. A recognition that not every day is a great day, that some days are better than others, and that things will work out was highlighted. A future optimism despite initial challenges in student life was expressed as important to maintain a sense of well-being. In general…don’t overthink. Take it easy, ‘cause…things will work out eventually (Interview 1).

The need for support category consists of two conceptions. “a supportive environment” and “the university as a facilitator”.

A supportive environment was related to both family and friends. Psychological support was described as parents expressing pride or support both because the parents were highly educated themselves, or because they had not had that opportunity. They haven’t had the opportunity to higher education, so they kind of wanted me to take the opportunity, as they didn’t have any (Interview 12). Additionally, support could be materialistic–parents who bought food for the students or gave them financial support. They have given me a little financial support when I need it, because they think it’s a nice thing to invest in (Interview 21). In their everyday life as students, support from fellow students was regarded as important. The feeling that the students wished each other well was highlighted by several of the participants. People are supportive. We do better if we help each other (Interview 20). In one of the programmes, only a pass/fail grade was given. This was regarded as a contributor to a culture of sharing and made for a less competitive culture. How to approach a feeling of lack of support from the university was also expressed. It should be someone to ask. More direct questions and answers. Not the answer, but where to find it (Interview 22).

The university as a facilitator is expressed in various ways. It is the students’ perception of their lecturers caring about them and caring about the students’ progress. It also applies to students’ perceptions of the programmes being well organized. A coordinated time schedule and clear and predictable expectations from the university were perceived significant dimensions. It’s important that things are clear, that you know where you are going and what you are doing (Interview 1). Space for working in groups were also important. This gave room for interaction with other students. We have lectures where we sit together around tables…then it is very natural to engage in conversations during breaks (Interview 1). In addition, easy access to administrative staff was highlighted.

Engagement from the lecturers were mentioned by several participants. The lecturers were expected to structure the syllabus. The knowledge is new to the students, and they need the lecturer to be structured. The presentation of the subject needs to be close to real life, and the relevance had to be made clear to the students. You can tell if the lecturer finds it interesting. It needs to be personal and dynamic (Interview 13). Some saw the organization of the lectures as important socially. For others, the social dimension and the study dimension were clearly divided. I am mainly here to learn…it’s nice to meet smart people who are nice and interesting, but that’s not why I’m here. I could probably get that elsewhere (Interview 19).

Facilitation of a social life from the university was experienced as a supportive dimension. Both activities related to the lectures, and extracurricular activities such as skiing trips that were taken into account and made room for in the formal time schedule. This was to facilitate social networking. The faculty facilitates for a lot of social activities (Interview 24). The students appreciated such efforts and felt highly regarded. When they spend so much time on us, you want to give something back (Interview 26).

Large classes were perceived a threshold. You know when you are in primary school and the teacher is in the classroom, and you can just ask. I miss that sometimes (Interview 5). In such settings, student assistants, fellow students and lecturers were regarded as relevant helpers, although fellow students and older students/student assistants seemed to be preferable.

Students perceive student life as a contributor to mental health and well-being demonstrated by the descriptive categories the need to belong and the need for support. Within every conception, there is a variation in the extent to which the participants perceive the categories related to mental health and well-being and how they perceive this. Within the category of the need to belong, small groups were a conception that was generally agreed upon as important for the participant. However, how these were constructed and by whom had little importance. The need for support was described through two different conceptions: a supportive environment and the university as a facilitator. The content of the conceptions shows the variety in students’ perceptions of how student life promotes mental health and well-being.

Our research showed that a sense of belonging can be accomplished by means of various measures such as small groups within the programme and leisure activities. These groups may be facilitated by the students, but also through the way the university and the different programmes are organized. Additionally, the attitudes of university staff towards the creation of small groups and facilitation of the establishment of a social network were of importance. Students have reported that “feeling valued and cared for, being listened to, having a sense of belonging, feeling part of a social environment and being able to participate in decision-making” are all important factors in enhancing a feeling of health and wellbeing [4]. This supports our findings that a sense of belonging is essential in the students’ perception of student life as promoting mental health and wellbeing.

Our findings about the students’ need to belong is supported by other research. Belonging is regarded as a fundamental motivation [27]. Baumeister et al. claim that there is a human drive to form positive, close attachments, and call this as “a need to belong” [27]. Their article has been widely cited and describes a natural desire to form relationships. According to Thomas, ‘belonging’ refers to the students’ sense of being included, accepted, and regarded as an important part of classroom life [28]. The majority of dropouts from higher education do so during their first year [29], and although there are a number of reasons for this [28], it indicates that the transitional phase is crucial in creating an arena that is perceived as promoting mental health and well-being. For students in higher education, a sense of belonging has also been highlighted as one out of eight fundamental intrapersonal competencies that are related to student retention and completion of higher education [30]. According to Dunne and Somerset, student health needs in general largely evolve around issues such as the stress of coping with a new environment, new people, loneliness and homesickness [1]. Finding a new social network is therefore of importance. According to Volstad et al. [31], small groups increase the sense of belonging, and constitute a contributor to establishing social networks.

According to Lambert et al., social relationships need to give a sense of belonging. They found a strong positive correlation between sense of belonging and meaningfulness. Moreover, an increase in the sense of belonging is followed by an increase in meaningfulness [32]. The link between these concepts is supported by our findings. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence (SOC) highlights meaningfulness as one of the three dimensions that build a sense of coherence. Antonovsky referred to this dimension as the motivational dimension of SOC [33]. People with a high sense of coherence feel that life makes sense and consider aspects of their lives as very meaningful. In this lies the implication that life aspects that are considered meaningful are worth investing and engaging in.

The close link between belonging, which our study shows as essential for students’ perceptions of student life as promoting mental health and well-being, and meaningfulness, underlines the importance of students developing a sense of belonging. Our findings demonstrate this can be achieved through various kinds of small groups. Participation in small groups inspires not only a sense of belonging, but also stimulates a sense of meaningfulness resulting in engagement and investment in student life. A high sense of meaningfulness (e.g., through a high sense of belonging) will stimulate acquisition of the resources at one’s disposal that will help in coping with the stressors that arise in this transitional time when starting as a student. The findings in this study do not necessarily support the concept of meaningfulness as of profound importance, but rather highlight the concept of belonging as important for students’ mental health and well-being in various ways. It may be concluded that creating a sense of belonging may increase the fundamental sense of meaningfulness.

A sense of belonging enhances academic engagement and attendance at teaching sessions [34,35]. As teaching sessions provide a setting where students create good relationships with fellow students, attendance is one of the situations that may facilitate a sense of belonging. Our findings are supported by Karaman et al. [21]. They found a strong correlation between a sense of belonging to the university and well-being. When the level of belonging to the university increases, students’ well-being levels are considered to increase as well.

The descriptive category the need for support could be associated with both academic and social activities. Arenas such as learning groups and leisure activities were created during the first period at the university. Our findings show that activities such as student societies, sports association for students and student subject associations could offer a sense of belonging, as could academic activities such as problem-based groups, learning groups with student assistants, etc. This also applies to participating in community activities related to the sponsorship week, where university and student life can be regarded as a community. Our findings show that the need for support is an important dimension for students to achieve a perception of good mental health and a feeling of well-being. This is also supported in earlier research. Our research shows the requirement for social support can be expressed and perceived in various ways. According to Zhou [36], social support consists of the following concepts: mutual assistance, guidance and validation of one’s life experiences and decisions. Support can be regarded as both informational, instrumental and emotional [36]. In our study, informational support referred to the time schedule and the fact that the university provided clear and predictable descriptions of its expectations. Instrumental support included, for example, financial help from parents, and emotional support was described through the feeling of fellow students wishing each other well or parents being proud of their children’s achievements. However, research shows that it is not the quality of the support that is of importance, but rather the perception of having support [36,37].

Participants in our study reported that social support allowed them to achieve better academically, and support from fellow students was regarded as important. These findings are supported by other research that shows that social support has proved to be the most protective factor for the students’ mental well-being [38]. According to Tinajero et al. [39], adjustment to university is easier when the students perceive social support. Perceived social support seems to improve academic achievement by reducing the stress many students experience in this transitional period [40]. Lack of social support has been linked to higher mortality rates [41]. Research has also shown that for both men and women in their first year as students, when family support decreases, psychological distress increases [42]. This implies the importance of support not only to promote mental health, but also to prevent ill health and enhance academic achievement.

The need for support described in the current study can also be related to Antonovsky’s dimension of manageability. Manageability points to the extent to which one feels that one has the necessary resources (GRR) available to meet life’s demands [33]. Our findings show that support from family, the university and fellow students is a resource that contributes to a sense of manageability. It can also be related to Antonovsky’s comprehensibility dimension. According to Antonovsky, this dimension of SOC is related to a perception of the surroundings as coherent and structured and presumably predictable [33]. This supports our findings about the university as a facilitator in the need for support category, as important for the students’ perception of student life as promoting mental health and well-being.

The ability to access social support has been shown to have positive effects on adjustment [36]. In the transitional period when starting student life, the need to belong and the need for support are intertwined. As our findings show, the feeling of belonging to a group may make a feeling of social support more accessible.

5 Methodological Considerations

The study was performed according to Lincoln and Guba’s evaluative criteria for trustworthiness [43]. This demands the establishment of credibility, dependability, transferability, confirmability, and authenticity. Credibility was ensured by verbatim transcription of the interview, and utterances were used in the article to illustrate the findings. Dependability was ensured by cooperation with fellow authors in the analysis process.

With the study’s thorough description of sample, participants and method, the findings can be regarded as transferable. Students were recruited to the study at the beginning of their second semester. At this time, the participants were still in the transitional phase, but would also have had time to establish a student life.

The participants were all students with high qualifications in study programmes that are associated with high grades and to a certain extent, status. There may be bias in the study as the students who were willing to participate were hard-working and very serious about their education, and many had worked hard to get accepted to the programme they were in [44]. This may affect some of the results, since themes such as self-confidence, good experiences with learning etc. may be different in other programmes that do not require such high grades. However, some of the psychology students were taking a one-year course with lower admission requirements. Their voices are also included in the material. Altogether, the variety of voices from different study programmes presented in the study helps to make our findings transferable to other students and student lives.

Confirmability was ensured by description of the analytical process. In phenomenography, a goal is to describe variations in conceptions of the phenomenon. Larsson et al. [45] recommend approximately 20 participants in a phenomenographic study to ensure variation. Appointments were made with 22 students. One did not take part due to a misunderstanding, and one interview was deleted by mistake. The data material gave thick description of the phenomenon and gave a good variation in perceptions.

Authenticity is a dimension in which the researcher approaches the data in a faithful manner and is able to express the emotional dimension of the participants’ perceptions. This is ensured by adopting a descriptive approach to how the data are conveyed, and the use of quotes.

Students perceive student life as promoting mental health and wellbeing in various ways through the descriptive categories “The need to belong” and “The need for support”. The categories demand engagement from students. They need to be active in making new friendships and networks in order to find a supportive environment to belong to. However, the findings also point to the university’s responsibility for facilitating the building of networks that promote new friendships and create a place to belong. This requires focus on how the programmes are organized and performed in order to facilitate and promote a feeling of mastery, thereby allowing students to achieve a balanced state of mind and an ability to respond appropriately to expected and unexpected stress.

The findings are consistent with the first call to action of the Health promoting universities and colleges- networks Okanagan charter, that states that health needs to be embedded into all aspects of campus culture [46]. Students need to be active, open and participatory, and universities should organize their programmes in a way that enables small groups of students to work together, such as students learning groups and facilitation of the sponsorship week. This will facilitate participation in network building activities and allow university staff to communicate a supportive attitude toward the students both academically and socially and enhance student life as promoting mental health and well-being, not only as an individual measure, but as a collective effort to improve the situation for first-year students.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Dunne, C., Somerset, M. (2004). Health promotion in university: What do students want? Health Education, 104(6), 360–370. DOI 10.1108/09654280410564132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Park, S. Y., Andalibi, N., Zou, Y., Ambulkar, S., Huh-Yoo, J. (2020). Understanding students’ mental well-being challenges on a university campus: Interview study. JMIR Formative Research, 4(3), e159624. DOI 10.2196/15962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Conley, C. S., Durlak, J. A., Dickson, D. A. (2013). An evaluative review of outcome research on universal mental health promotion and prevention programs for higher education students. Journal of American College Health, 61(5), 286–301. DOI 10.1080/07448481.2013.802237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Newton, J., Dooris, M., Wills, J. (2016). Healthy universities: An example of a whole-system health-promoting setting. Global Health Promotion, 23(1 Suppl), 57–65. DOI 10.1177/1757975915601037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Cawood, J., Dooris, M., Powell, S. (2010). Healthy universities: Shaping the future. Perspectives in Public Health, 130(6), 259–260. DOI 10.1177/1757913910384055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Dooris, M. (2001). The “health promoting university”: A critical exploration of theory and practice. Health Education, 101(2), 51–60. DOI 10.1108/09654280110384108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Schofer, E., Meyer, J. W. (2005). The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review, 70(6), 898–920. DOI 10.1177/000312240507000602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Universities UK (2021). Higher education in numbers. https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/facts-and-stats/Pages/higher-education-data.aspx. [Google Scholar]

9. Statistics Norway (2019). Students in higher education. https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/statistikker/utuvh. [Google Scholar]

10. Viskovich, S., Pakenham, K. I. (2020). Randomized controlled trial of a web-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) program to promote mental health in university students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(6), 929–951. DOI 10.1002/jclp.22848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Axinn, W. G., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D. D. et al. (2016). Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2955–2970. DOI 10.1017/S0033291716001665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Stallman, H. M. (2010). Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Australian Psychologist, 45(4), 249–257. DOI 10.1080/00050067.2010.482109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Knowlden, A. P., Sharma, M., Kanekar, A., Atri, A. (2013). Sense of coherence and hardiness as predictors of the mental health of college students. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 33(1), 55–68. DOI 10.2190/IQ.33.1.e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sivertsen, B., Råkil, H., Munkvik, E., Lønning, K. J. (2019). Cohort profile: The SHoT-study, a national health and well-being survey of Norwegian university students. BMJ Open, 9(1), e025200. DOI 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Usher, W. (2020). Living in quiet desperation: The mental health epidemic in Australia’s higher education. Health Education Journal, 79(2), 138–151. DOI 10.1177/0017896919867438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Donovan, R. J., James, R., Jalleh, G., Sidebottom, C. (2012). Implementing mental health promotion: The act-belong–commit mentally healthy WA campaign in Western Australia. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 8(1), 33–42. DOI 10.1080/14623730.2006.9721899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bang, K. S., Lee, I., Kim, S., Lim, C. S., Joh, H. K. et al. (2017). The effects of a campus forest-walking program on undergraduate and graduate students’ physical and psychological health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7), 728. DOI 10.3390/ijerph14070728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ridner, S. L., Newton, K. S., Staten, R. R., Crawford, T. N., Hall, L. A. (2015). Predictors of well-being among college students. Journal of American College Health, 64(2), 116–124. DOI 10.1080/07448481.2015.1085057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Fernandez, A. E., Howse, M., Rubio-Valera, K., Thorncraft, J., Noone, X. L. et al. (2016). Setting-based interventions to promote mental health at the university: A systematic review. International Journal of Public Health, 61(7), 797–807. DOI 10.1007/s00038-016-0846-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Karaman, O., Cirak, Y. (2017). The belonging to the university scale. Acta Didactica Napocensia, 10(2), 1–20. DOI 10.24193/adn.10.2.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Karaman, Ö., Tarim, B. (2018). Investigation of the correlation between belonging needs of students attending university and well-being. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(4), 781–788. DOI 10.13189/ujer.2018.060422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Knapstad, M., Sivertsen, B., Knudsen, A. K., Smith, O. R. F., Aaro, L. E. et al. (2021). Trends in self-reported psychological distress among college and university students from 2010 to 2018. Psychological Medicine, 51(3), 470–478. DOI 10.1017/S0033291719003350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Marton, F., Booth, S. (2009). Learning and awareness. The educational psychology series. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

24. Norwegian National Research Ethics Committees (2019). General guidelines for research ethics. https://www.etikkom.no/en/ethical-guidelines-for-research/general-guidelines-for-research-ethics/. [Google Scholar]

25. Dahlgren, L. O., Fallsberg, M. (1991). Phenomenography as a qualitative approach in social pharmacy research. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 8(4), 150–156. [Google Scholar]

26. Barnard, A., Gerber, R. (1999). Understanding technology in contemporary surgical nursing: A phenomenographic examination. Nursing Inquiry, 6(3), 157–166. DOI 10.1046/j.1440-1800.1999.00031.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Baumeister, R. F., Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. DOI 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Thomas, L. (2012). Building student engagement and belonging in Higher Education at a time of change. Paul Hamlyn Foundation, 100, 1–99. [Google Scholar]

29. Rausch, J. L., Hamilton, M. W. (2006). Goals and distractions: Explanations of early attrition from traditional university freshmen. Qualitative Report, 11(2), 317–334. [Google Scholar]

30. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (2017). Supporting students’ college success: The role of assessment of intrapersonal and interpersonal competencies. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

31. Volstad, C., Hughes, J., Jakubec, S. L., Flessati, S., Jackson, L. (2020). You have to be okay with okay: Experiences of flourishing among university students transitioning directly from high school. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1834259. DOI 10.1080/17482631.2020.1834259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F. (2013). To belong is to matter. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. DOI 10.1177/0146167213499186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. A Joint publication in the Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series and the Jossey-Bass health series. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

34. Wilson, D., Jones, D., Bocell, F., Crawford, J., Kim, M. J. et al. (2015). Belonging and academic engagement among undergraduate STEM students: A multi-institutional study. Research in Higher Education, 56(7), 750–776. DOI 10.1007/s11162-015-9367-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Oldfield, J., Rodwell, J., Curry, L., Marks, G. (2017). A face in a sea of faces: Exploring university students’ reasons for non-attendance to teaching sessions. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(4), 443–452. DOI 10.1080/0309877X.2017.1363387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhou, E. S. (2014). Social Support. In: Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Michalos, A. C.Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

37. Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review. In: Friedman, H. S. (Eds.The Oxford handbook of health psychology, pp. 189–214. UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

38. Bíró, É., Veres-Balajti, I., Kósa, K. (2016). Social support contributes to resilience among physiotherapy students: A cross sectional survey and focus group study. Physiotherapy, 102(2), 189–195. DOI 10.1016/j.physio.2015.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tinajero, C., Martínez-López, Z., Rodríguez, M. S., Guisande, M. A., Páramo, M. F. (2015). Gender and socioeconomic status differences in university students’ perception of social support. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(2), 227–244. DOI 10.1007/s10212-014-0234-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mackinnon, S. P. (2012). Perceived social support and academic achievement: Cross-lagged panel and bivariate growth curve analyses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(4), 474–485. DOI 10.1007/s10964-011-9691-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377–387. DOI 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Arias-de la Torre, J.,Fernández-Villa, T., Molina, A. J., Amezcua-Prieto, C., Mateos, R. et al. (2019). Psychological distress, family support and employment status in first-year university students in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1209. DOI 10.3390/ijerph16071209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Cope, D. G. (2014). Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(1), 89–91. DOI 10.1188/14.ONF.89-91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sandelowski, M. (1986). The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science, 8(3), 27–37. DOI 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Larsson, J., Holmström, I. (2009). Phenomenographic or phenomenological analysis: Does it matter? Examples from a study on anaesthesiologists’ work. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 2(1), 55–64. DOI 10.1080/17482620601068105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. International Conference on Health Promoting Universities & Colleges (2015). Okanagan Charter: An international charter for health promoting universities & colleges.https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/53926/items/1.0132754 [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |