| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.011168

ARTICLE

Media Coverage of Terrorism and Mental Health Concerns among Youth: Testing Moderated Mediation by Spirituality and Resilience

1York University, Toronto, Canada

2Riphah Institute of Clinical and Professional Psychology, Riphah International University, Lahore, 54590, Pakistan

3Institute of Communication Studies, University of the Punjab, Lahore, 54590, Pakistan

*Corresponding Author: Mian Ahmad Hanan. Email:hanan_mian@hotmail.com

Received: 16 June 2020; Accepted: 21 December 2020

Abstract: Previous research on media coverage of terrorism and its associated psychological consequences was explored internationally particularly after 9/11 attacks in the US. Also, the constructive role of resilience in this traumatic era has also been explored internationally. However, some studies have been conducted on the effect of media coverage of national terrorism on people that have endured a nearby terrorist attack. Moreover, knowledge about how the media coverage of terrorism, as a secondary source of evidence, can have devastated effects on native’s mental health and how resilience work in this relationship is rather limited. For example, it is possible that different cultures have their own coping strategies (resilience & spirituality) to be adopted as they perceive and respond to terrorism coverage on media differently. Hence, this study examines the moderated role of spirituality as an adaptive mechanism along with resilience as a mediating factor in the relationship between media coverage of terrorists’ incidents and mental health concerns such as perceived stress, generalized anxiety and perceived fear among Pakistani youth. The findings show significant results as expected, people having high level of spirituality effectively cope with the media coverage of terrorist incidents by facing the situation with more resilient personality and therefore experience less mental health concerns compared to those with low level of spirituality.

Keywords: Anxiety; fear; online terrorism exposure; psychological concerns; resilience; stress; terrorism coverage

Perceptions of reality are shaped not only by what we experience directly in our daily lives, but by what we read, see, and hear in various mass communication channels. Media has power and ability to shape the mind set of people and public opinion. The public perceptions of the world around us are influenced by mass media is indisputable. Moreover, media provide a platform where we get direct experience of an incident happening far away from us. After the Second World War, electronic media emerged as a powerful source of information. During the 1960s, the rate of crime increased exponentially in many states of America. Researches were conducted to explore the reasons behind this phenomenon. The results lead to the conclusion that exposure to televised violence played a role in creating psychological distress that leads to an outburst of aggression. The children and adolescents spent less time engaging in physical activities as they spent more time watching television with no censor. It is an established fact that violence is dangerous for all, whether it is being experienced either through media technologies or being committed by the individual himself. In the past few decades, the world has experienced the worst kind of violent acts in the form of terrorism that has been described as a vicious act of cruelty, resulting in disastrous consequences. The word ‘terrorism’ is originated from the Latin word terrere, which means ‘to frighten’. There is no consensus definition of terrorism because it is a complex concept [1]. It is often defined as the illegal use of force against an individual or government to gain nefarious objectives. Undoubtedly, it has posed serious threats to peace, stability, and security. It is categorized as one of the most terrible categories of violence. In short, terrorism always produces horrible results in the form of destruction, fear, confusion, and chaos [2]. In the present age, people are connected through social networks. The latest information and communication technology have reduced all distances. The world has become a “Global Village” in real sense. Right now, it is almost impossible to censor news. Therefore, any news such as terrorist incidents immediately disseminated around the globe through media and social networking websites. People share news and their views, videos, and pictures that resulted in escalating public risk perception as well as increasing the level of psychological distress.

News media is considered to have a symbiotic relationship with terrorism (Wilkinson, 1997). In addition to physical violence, terrorist groups want publicity for their cause. In this regard, they consider media as an effective tool for attaining public attention. Through different communication mediums, they also propagate their extremist ideologies [3]. Their main objective is not how many people died but how many people are watching [4]. It is clear from previous scholarly studies that media coverage of tragic events cultivate fear and develop post-traumatic stress. This particular study aims to identify the relationship between media coverage of terrorism and psychological concerns through the mediating role of trait resilience in the context of Pakistan.

There are varied opinions about the media coverage of terrorism. In this regard, two schools of thought are prominent who have their unique stance on this particular issue. The first school unconditionally support media by arguing that the media portrays the real picture of society. It is the responsibility of the media to report what happened in society. The second school believes that media glorifies criminal activities. This school of thought also argues that the excessive coverage of terrorism indirectly supports terrorist groups.

Generally speaking; the role of independent media is acknowledged all over the world. It is expected from media to disseminate factual information. The first school believed that the media portrays reality as it exists while covering terrorism. Former Prime Minister of UK Margaret Thatcher supported the second school stating that media was providing “the oxygen of publicity” on which terrorist organizations rest on [5]. According to Hoffman [6] terrorists cannot fulfill their nefarious objectives provided that the media do not give coverage to their violent acts. In this way, the impact of the terrorist act will remain narrowly confined. Similarly, Ganor [7] believed that the main objective of terrorists is not to kill people but to gain massive media coverage so that they may achieve their real objectives by creating terror in society. In reality, terrorist organizations use media to gain attention, recognition, and legitimacy. Currently, terrorist organizations are using internet as an instrument for propagating their cause and violent activities [8].

It is a fact that the media has a strong influence on the audience. Different information mediums, especially television, affect the perception of viewers. Nauert [9] conducted a study to measure the effects of media coverage of terrorist incidents on emotions of audience and revealed that the images of violence produces stress hormones and increases heart rate and blood pressure. Several communication theories described that media indirectly promotes terrorist agenda. Lasswell in his Transmission model argued that the message source controls the communication process and it leaves powerful effects on the receiver. It simply means that whatever is published or broadcasted, have a great influence on the audience [10]. Framing is a popular theory in communication study. It also links terrorism with media. Herman et al. [11] discussed that the framing of events by media can make an event ordinary or extra-ordinary. Media frames events keeping in view the owner’s interest and editorial policy. In other words, framing shapes the public mind taking into consideration the media’s perspective [12]. King et al. [13] claimed that media frames not only make a message extraordinary but also make it easier to understand. Framing theory postulates that the public recognizes an issue in the way as it is framed by the media [14]. Another point worth mentioning is the portrayal of violent content and live coverage of terrorist acts that lead viewers towards the psychologically disrupting situation. Most importantly, the media dependency theory claimed that the media has powerful impacts on those individuals who often rely on media to satisfy their needs [15]. Through media dependency theory, we can understand how media content reshapes beliefs, feelings, and behaviors.

To summarize, communication scholars believed that a strong relationship exists between media coverage and terrorism. At present, terrorism has evolved differently and the media coverage as one of the major reasons for this phenomenon. Media functions as an enabler of terrorism [16]. The review of communication theories in the context of media coverage of terrorism clearly showed that violent content and media coverage of terrorism have a great influence on human behavior. Live coverage of terrorism creates fear, anxiety, and anger among masses.

A number of studies have explored the relationship between media coverage of terrorism and psychological distress. Featherstone et al. [17] maintained that the basic objective of terrorists’ is to draw media attention, to promote their cause and to create the environment of fear in the target audience. The extensive media coverage of terrorist attacks fulfills their objectives. By creating the environment of fear, anxiety and distress. Galea et al. [18] study indicated that individuals who were more inclined to watch violent content such as crime news and terrorist incidents had fallen prey to mental disturbance, mood swings and anxiety. Several studies revealed that exposure to media coverage of terrorism increases the risk of developing an anxiety disorder. Comer et al. [19] maintained that terrorism coverage generated serious psychological issues among children. After watching violent images, children were found in a state of emotional and psychological trauma. Another research analyzed the psychological impacts of the 11 September, 2001 terrorist attacks on World Trade Center and Pentagon and revealed that the media exposure plays a role in the development of psycho-symptomology. Slone [20] measured differential anxiety responses of participants in an experiential study of exposure to graphic violence scenes and clips about terrorists’ incidents and threats to national security revealed that there was no increase in level of anxiety among those who were not expose to violent contents. In addition, Ahern et al. [21] argued that live media coverage of terrorist incidents and violence can have the similar psychological impact on viewers as being directly present in that situation.

Similarly, previous studies also showed that terrorism-related news increases the stress level. Keinan et al. [22] claimed that news coverage of terrorism has detrimental effects in the form of stress disorder. Holman et al. [23] conducted an online survey among a sample of 4,675 adults residing in Boston and New York about the Boston Marathon bombing 2013. The findings revealed that coverage of terrorist activities causes severe stress. The prolonged coverage of terrorism also created substantial stress related to symptomatology. Anxiety and fear are the sorts of phenomenon that go hand in hand. An excessive amount of anxiety leads towards traumatic circumstances. Müller [24] maintained that terrorist incidents have stronger psychological rather than physical effects on target population. Sherrieb et al. [25] conducted a study to assess the effects of brief exposure to prolonged exposure of terrorism coverage on the emotions of the audience revealed that the constant viewing of threatening images and violence exposure drastically increase stress and fear. Ahmed et al. [26] assess the levels of stress caused by terrorist incidents among 291 students from various universities located in Karachi, Pakistan and maintains that a majority of students had mild stress levels because of resilience resulted due to prolonged duration and exposure to terrorist activities. It concludes that terrorist incidents not only affect social life but also restrict social actives of masses. Kausar et al. [27] studied the influence of news coverage of terrorism and perceived stress. This study resulted that male members of society are more tended towards watching terrorism news. Furthermore, males adopted practical while female fellow religious focused stress coping strategies. Nellis et al. [28] conducted a telephone survey among 532 respondents living in New York and Washington. This study found that media attention to terrorist attacks has a positive association with the perceived risk of terrorism to self and others. Terrorism, whether experienced first-hand or vicariously through the media, creates effects like anxiety, stress, and fear by undermining people’s sense of control over their mental states [29].

The main purpose of terrorist groups is to create fear in society and make people anxious. Maguen et al. [30] claimed that majority of people are resilient and recover over time. There is no denying the fact that the ability of individuals to display resilience changes over time [31]. Bonanno [32] argued that resilience may be fairly common in adverse circumstances. Another study claimed that the respondents scoring high on a measure of trait resilience. They were utilizing positive emotions to tackle psychological distress created in the result of the 11 September, 2001 terrorist attacks [33]. Liu et al. [34] revealed that due to resilience to terrorism there is no long-term and powerful effects of terrorism on tourism in most of the countries of world. Likewise, MacDermid Wadsworth [35] claimed that individuals and families demonstrated striking levels of resilience despite serious challenges of war and terrorism.

Spirituality is a major source of resilience that develop the ability to cope and improve psychological well-being [36]. Womble et al. [37] claimed that spirituality is a significant predictor of health resilience. Similarly, the study of Reutter et al. [38] found spirituality as an effective resiliency resource. Their study also found the positive mediating role of spirituality. Hourani et al. [39] found that military personnel with low spirituality level showed higher levels of depression and stress. Khan et al. [40] examined the effects of religious orientation on psychological distrust collecting data from 207 university students. They found that a higher level of spirituality diminishes the effects of psychological distress. Young et al. [41] found a significant moderating effects of spirituality on depression and fear. Another study by Kim et al. [42] observed the same effects. In addition, Koenig [43] argued that spirituality is a powerful source of comfort and hope, especially in adverse circumstances. The main objectives of this study are as follows. (1) To explore the relationship between media coverage of terrorism and mental health concerns such as (PF), perceived fear, (GA), general anxiety, and (PS), perceived stress. (2) To investigate the mediating role of trait resilience between the relationship of terrorism and mental health concerns. (3) To investigate the moderating effect of spirituality in the relationship of terrorism and mental health concerns via trait resilience.

This study empirically verifies the following hypotheses:

H1: Coverage of terrorist incidents is positively associated with mental health concerns (PF, GA & PS) in adults.

H2: Trait resilience is negatively associated with mental health concerns (PF, GA & PS) in adults.

H3: Trait resilience mediates the relationship between media coverage of terrorist incidents and mental health concerns (PF, GA & PS) in adults.

H4: Spirituality moderates the mediating role of trait resilience in the relationship between media coverage of terrorist incidents and mental health concerns (PF, GA & PS) in adults, for the individuals having high level of spirituality experiences less mental health concerns with high level of exposure to media coverage of terrorist incidents compared to individuals having low level of spirituality.

Participants were consisted of 322 young adults selected from various public and private higher education institutes of Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan with the help of non-probability purposive sampling technique. Majority of the participants (72.4%) belongs to 18–24 years of age while, 27.6% participants belongs to age group of 25–30 years. Out of these participants, 46.2% were females while 53.8% were males. Furthermore, only those respondents were included in this study who watches terrorism related coverage on electronic media. Moreover, the participants average hours of exposure to terrorism related electronic media coverage is high with M = 4.34; SD = 1.63).

Following assessment measures were used in the present study in order to collect data with the help of survey research design and these includes: a) State-trait Resilience Scale [44], from this scale, only trait resilience scale, consisted of 18 items was used to assess the level of resilience as a personality factor among the respondents. In this scale, participants had to respond to these items using 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1 = Strongly agree to 5 = Strongly disagree).

They had to rate themselves on each item from childhood, moreover, the scale has been divided into inter and intra trait resilience, but the composite can also be used to assess the overall trait level of resilience.

In the current study, the overall reliability of the trait resilience scale was found to be α = 0.76; b) Perceived Stress Scale, PSS [45] is a 10 item revised questionnaire use in this study to evaluate how much one sees parts of one’s life as out of control, erratic, and over-burdening. individuals are asked to react to every statement on a 5-point Likert scale extending from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), demonstrating how they felt on the past month; c) Generalize Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire GADQ, [46] where respondents were approached to depict how regularly they felt during the most recent fourteen days, they have been irritated by every one of the 7 center proclamations utilizing reaction alternative, for example, “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day”; d) Terrorism Catastrophizing Scale TCS [47] is a 13 item scale for the assessment of future fear related to terrorism in one’s life rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). For instance, the items include ‘there is little I can do to protect myself from terrorism’ and the overall alpha coefficients of the scale in the current study was 0.80.

Respondents were instructed to complete the questionnaires after taking written informed consent from them, which clearly states that no remuneration was given for their participation, and members were allowed as much time varying to finish the surveys, also confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed of privacy. They were further instructed to fill the survey by keeping in mind the terrorist attacks from 9 January 2019 to 30 April, 2019 and its associated media coverage. The participants were mainly from introductory courses from various academic disciplines simultaneously from varied academic institutions. Either a trained research assistant or the author(s) was present at each administration to provide instructions and collect consent forms from participants.

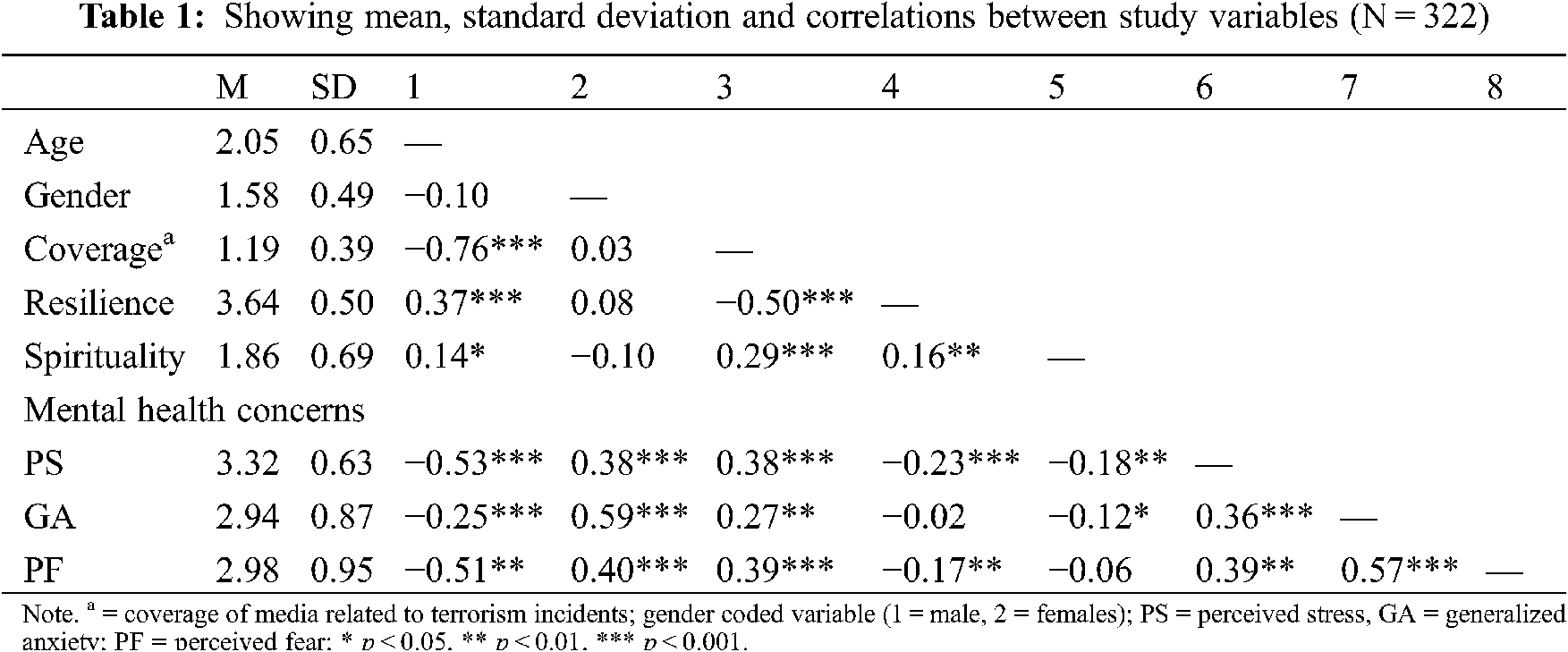

The data from the current study was analyzed using IBM-SPSS, initially, the descriptive statistics and the correlations among the study variables were calculated and the findings were given in Table 1.

The results from the correlational analysis revealed that live media coverage of terrorist incidents is positively associated with mental health concerns (stress, anxiety and fear) while it is negatively related with resilience and spirituality. Similarly, resilience is positively associated with spirituality and negatively associated with mental health concerns (stress, anxiety and fear).

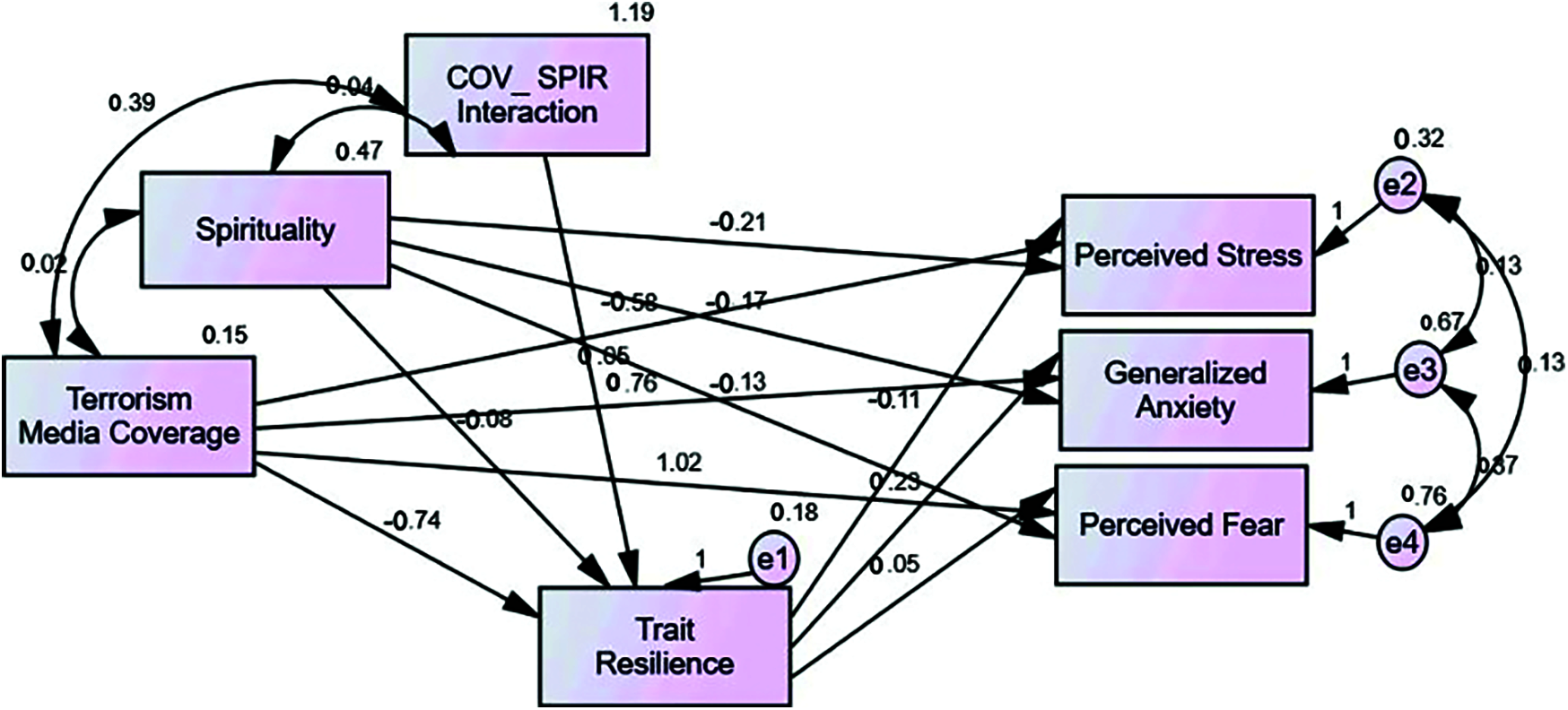

4.2 Moderated Mediation Analysis

Structural Equation Modeling through Analysis of Moment Structure (AMOS) was used to test our study hypothesis. Initially, for moderation interaction term between Coverage * Spirituality was created with the help of compute command using SPSS and then standardized scores of this interaction variable was used for further analysis using AMOS, bootstrapping of 2000 samples was conducted with 95% confidence interval. The results revealed an overall model fit with a significant chi-square and adequate model fit indices (χ²(3) = 28.94, p = <0.001, CFI = 0.89, TLI = 0.80, RMSEA = 0.05). The final model with all the paths was given in Fig. 1 and the interaction plot for the effects of moderation is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 1: Moderated mediation analysis path diagram from AMOS Note: Moderated mediation analysis for the influence of coverage of terrorist incidents and its impact on mental health concerns (PS = perceived stress, GA = generalized anxiety, PF = perceived fear).

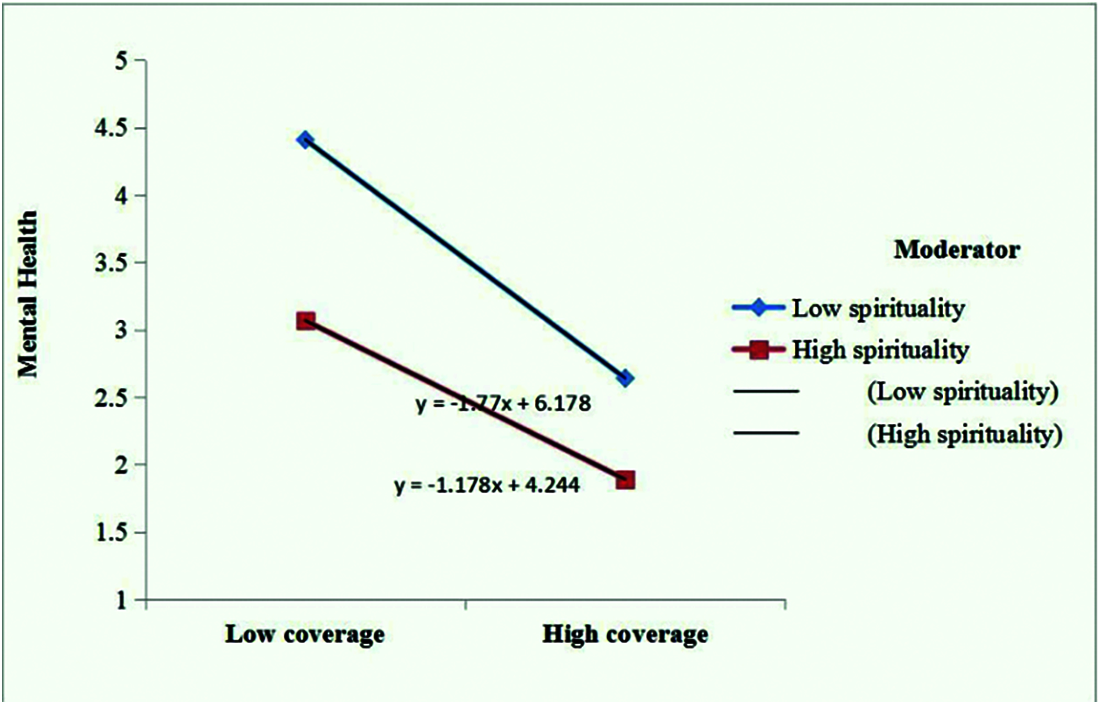

Figure 2: Showing the interaction plot between coverage of terrorism incidents with levels of spirituality on level of mental health concerns

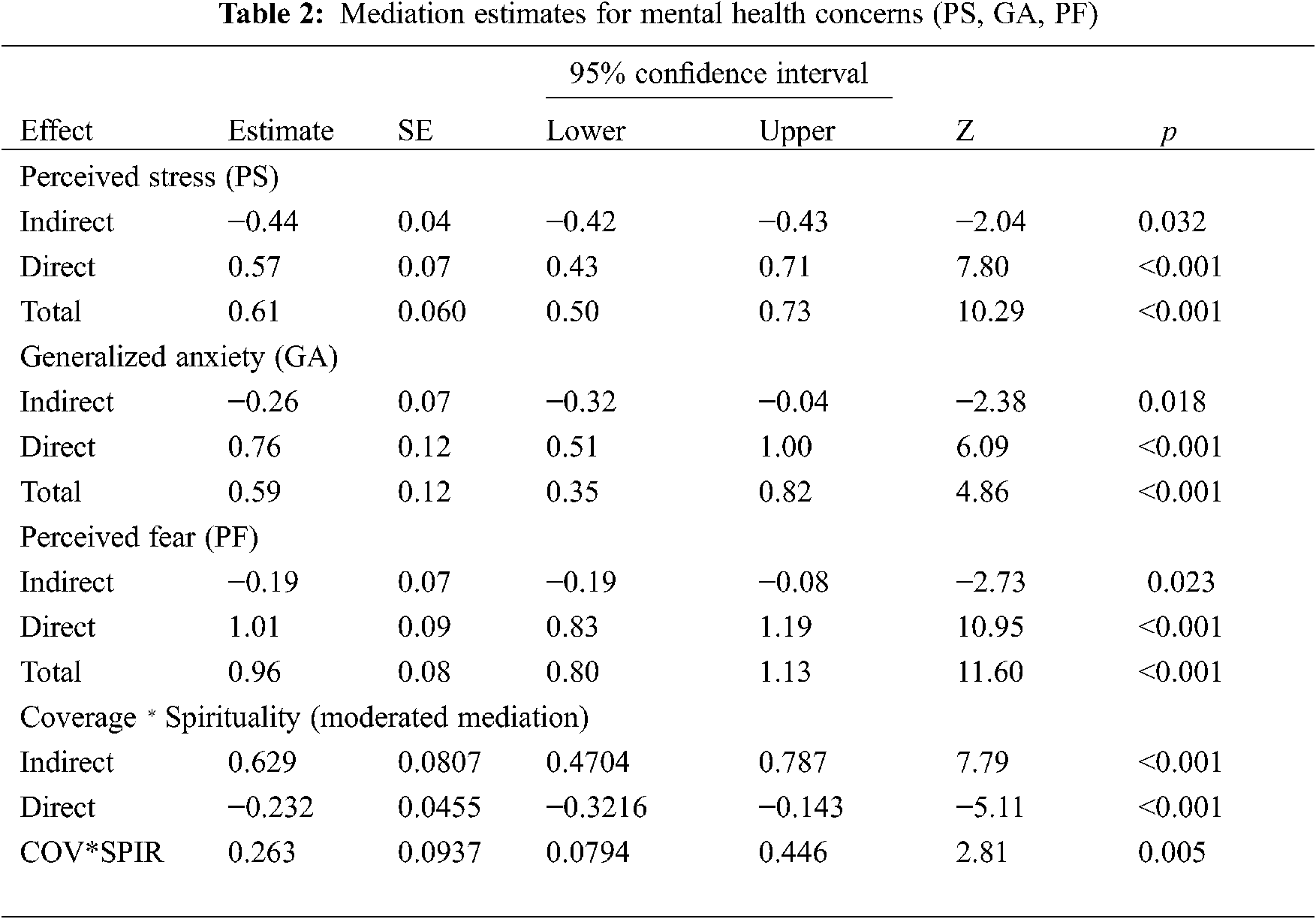

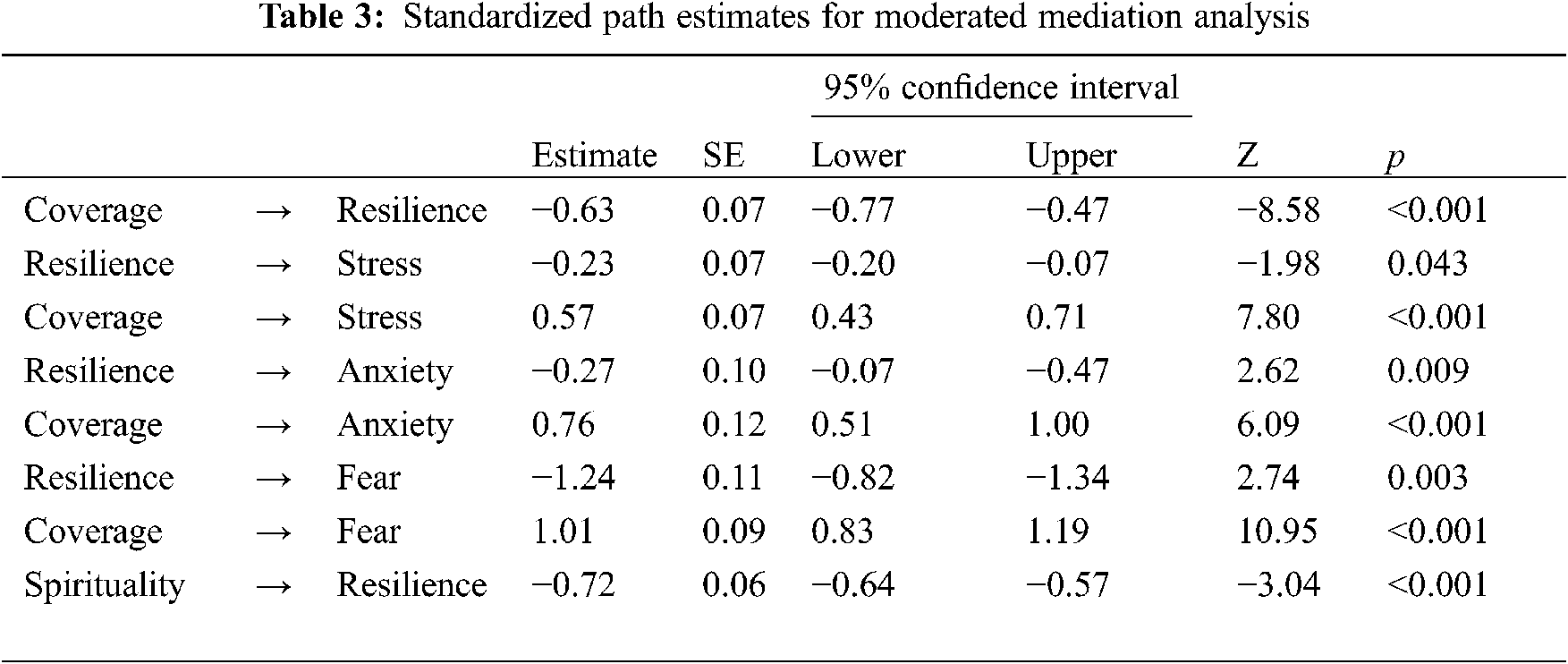

As there are three domains of mental health concerns including perceived stress, generalized anxiety and perceived fear, so in order to explore the separate effect of mediators on all three domains of mental health concerns AMOS Plugins were run separately in for each domain as a separate dependent variable and the results were given in Table 2, while the standardized path estimates were given in Table 3.

The results from the above table revealed the significant indirect effect of resilience in the relationship between media coverage of terrorist incidents and mental health concerns (PS, GA and PF) among the young adults. Moreover, these findings indicated that the indirect effect of resilience on PS, GA and PF was negative which clearly indicated that individual having high level of resilience were showing less mental health concerns in terms of stress, anxiety and fear than people having low level of resilience besides having exposed to media coverage of terrorism, this clearly highlighted the positive and protective role of resilience in trauma related incidents. Furthermore, the results also highlighted that there was a significant moderated mediation effect of spirituality, in order to have a significant effect of moderation in the mediation analysis, the direct effect of spirituality to resilience should be significant, and the findings from Table 3 indicated the significant negative effect of spirituality on resilience (β = −0.72, p < 0.001), which indicated that the level of spirituality significantly influences the relationship between media coverage of terrorist incidents and mental health concerns (PS, GA, PF) via resilience.

Similarly, the significant interaction effect was also analyzed and presented with the help of interaction plots using stat tool packages.

The findings from the interaction plot significantly highlighted the negative relationship between spirituality and coverage interaction with over all mental health concerns (PF, GA, PS). This further revealed that with the high level of spirituality among the viewers watching more media coverage of terrorism incidents their mental health concerns significantly decreases compared to those having low spirituality level but high exposure to coverage of terrorism incidents. This further illustrated that spirituality plays a constructive role in the realms of trauma related mental health concerns.

This study discussed the relationship between media coverage of terrorism incidents and mental health concerns such as anxiety, stress, and fear through investigating the moderating effects of spirituality and the mediating role of human resilience. The results of the study concluded that media coverage of terrorism was significantly correlated with all constructs of mental health concerns. Human resilience was found to be negatively associated with mental health concerns. Moreover, the results of moderated mediation analysis proved that the level of spirituality affects the relationship between media coverage of terrorism and mental health concerns via resilience.

As hypothesized, this study found that live media coverage of terrorist activities is positively associated with mental health concerns (stress, anxiety, and fear). Table 1 shows the findings related to the positive relationship between media coverage of terrorism and mental health concerns. These findings are compatible with previous studies [9,19,21,22,24,28,29]. Similarly, H2 is also proved as the results clearly showed that trait resilience is negatively associated with mental health concerns. This is also consistent with previous scholarly studies [33–35]. This clearly showed that traits of human resilience decrease psychological concerns.

Furthermore, the results of this study support the moderating effects of spirituality. As shown in the result section, the level of spirituality significantly influences the relationship between media coverage of terrorism and mental health concerns. Previous studies also revealed that spirituality is a main source of resilience that reduce psychological concerns and provide comfort [36,38,40,43]. This study also proved that media coverage of terrorism has minimal effects on those individuals who are more inclined towards spirituality.

This study significantly contributed to the existing literature. It enhances our understanding by explaining the relationship between media coverage of terrorism and mental health concerns in the context of Pakistan. Besides, it also finds out the moderating role of spirituality and mediating effects of human resilience. This study has some limitations including it limits generalizability. The results of this study cannot be generalized to the overall population of Pakistan because of employing non-probability sampling technique. Further studies need to generalize results with large sample size. It also remains for future studies to identify the effects of other communication mediums such as interpersonal communication. Similarly, effects of catastrophic events coverage should be examined on other dimensions of psychological concerns such as anger, hopelessness and so on.

Summarizing the above discussion, it is concluded that media coverage of terrorism is positively associated with mental health concerns such as anxiety, stress, and fear. Individuals having a higher level of resilience are less influenced by media coverage of terrorism. Moreover, spirituality also affects the relationship between media coverage of terrorism and mental health concerns via resilience. The higher level of spirituality decreases mental health concerns.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Best, S., Nocella, A., Anthony, J. (2004). Defining terrorism. Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal, 2(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

2. Laqueur, W. (2000). The new terrorism: Fanaticism and the arms of mass destruction. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

3. Weimann, G. (2014). New terrorism and new media, vol. 2. Washington, DC: Commons Lab of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. [Google Scholar]

4. Jenkins, B. (1975). International terrorism: A balance sheet. Survival, 17(4), 158–164. DOI 10.1080/00396337508441554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wilkinson, P. (1997). The media and terrorism: A reassessment. Terrorism and Political Violence, 9(2), 51–64. DOI 10.1080/09546559708427402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hoffman, B. (2006). Inside terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

7. Ganor, B. (2002). Israel’s counter-terrorism policy: 1983–1999 efficacy versus liberal democratic values. (Ph. D. Dissertation). Hebrew University, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

8. Torres-Soriano, M. R. (2011). The vulnerabilities of online terrorism. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 35(4), 263–277. DOI 10.1080/1057610X.2012.656345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Nauert, R. (2008). Impact of television violence. https://www.psychcentral.com/news/2008/10/02/impact-of-televisionviolence/3050.html. [Google Scholar]

10. Baran, S. J., Davis, D. K. (2003). Mass communication theory: Foundation ferment, and future. 3rd editionToronto, Canada: Thomson Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

11. Herman, E. S., Chomsky, N. (2002). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of mass media. 2nd edition New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

12. Nelson, T. E., Clawson, R. A., Oxley, Z. M. (1997). Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance. American Political Science Review, 91(3), 567–583. DOI 10.2307/2952075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. King, C., Lester, P. M. (2005). Photographic coverage during the Persian Gulf and Iraqi wars in three US newspapers. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 82(3), 623–637. DOI 10.1177/107769900508200309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Scheufele, D. A., Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 9–20. DOI 10.1111/j.0021-9916.2007.00326.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ball-Rokeach, S. J., DeFleur, M. L. (1976). A dependency model of mass-media effects. Communication Research, 3(1), 3–21. DOI 10.1177/009365027600300101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lumbaca, S., Gray, D. H. (2011). The media as an enabler for acts of terrorism. Global Security Studies, 2(1), 45–54. [Google Scholar]

17. Featherstone, M., Holohan, S., Poole, E. (2010). Discourses of the War on terror: Constructions of the islamic other after 7/7. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 6(2), 169–186. DOI 10.1386/mcp.6.2.169_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Galea, S., Ahern, J., Resnick, H., Kilpatrick, D., Bucuvalas, M. et al. (2002). Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York city. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(13), 982–987. DOI 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Comer, J. S., Kendall, P. C. (2007). Terrorism: The psychological impact on youth. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 14(3), 179–212. DOI 10.1111/j.14682850.2007.00078.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Slone, M. (2000). Responses to media coverage of terrorism. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 44(4), 508–522. DOI 10.2307/174639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ahern, J., Galea, S., Resnick, H., Kilpatrick, D., Bucuvalas, M. et al. (2002). Television images and psychological symptoms after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 65(4), 289–300. DOI 10.1521/psyc.65.4.289.20240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Keinan, G., Sadeh, A., Rosen, S. (2003). Attitudes and reactions to media coverage of terrorist acts. Journal of Community Psychology, 31(2), 149–165. DOI 10.1002/jcop.10040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Holman, E. A., Garfin, D. R., Silver, R. C. (2014). Media’s role in broadcasting acute stress following the Boston marathon bombings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(1), 93–98. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1316265110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Müller, J. W. (2006). ‘An irregularity that cannot be regulated’: Carl Schmitt’s theory of the partisan and the “war on terror”. Jurisprudence and the War on Terrorism’ Conference at Columbia Law School. https://www.princeton.edu/~jmueller/Schmitt-WarTerror-JWMueller-March2007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

25. Sherrieb, K., Norris, F. H. (2013). Public health consequences of terrorism on maternal-child health in New York city and Madrid. Urban Health, 90(3), 369–387. DOI 10.1007/s11524-012-9769-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ahmed, A. E., Masood, K., Dean, S. V., Shakir, T., Kardar, A. A. H. et al. (2011). The constant threat of terrorism: Stress levels and coping strategies amongst university students of karachi. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 61(4), 410. [Google Scholar]

27. Kausar, R., Anwar, T. (2010). Perceived stress, stress appraisal and coping strategies used in relation to television coverage of terrorist incidents. Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 8(2), 119–131. [Google Scholar]

28. Nellis, A. M., Savage, J. (2012). Does watching the news affect fear of terrorism? The importance of media exposure on terrorism fear. Crime & Delinquency, 58(5), 748–768. DOI 10.1177/0011128712452961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Klar, Y., Zakay, D., Sharvit, K. (2002). ‘If I don’t get blown up…’: Realism in face of terrorism in an Israeli nationwide sample. Risk, Decision and Policy, 7(2), 203–219. DOI 10.1017/s1357530902000625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Maguen, S., Papa, A., Litz, B. T. (2008). Coping with the threat of terrorism: A review. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 21(1), 15–35. DOI 10.1080/10615800701652777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. MacDermid, S. M., Samper, R., Schwarz, R., Nishida, J., Nyaronga, D. (2008). Understanding and promoting resilience in military families. West Lafayette, IN: Military Family Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

32. Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events?. American Psychologist, 59(1), 20. DOI 10.1037/0003-066x.59.1.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu, A., Pratt, S. (2017). Tourism’s vulnerability and resilience to terrorism. Tourism Management, 60, 404–417. DOI 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. MacDermid Wadsworth, S. M. (2010). Family risk and resilience in the context of war and terrorism. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 537–556. DOI 10.1111/j.l741-3737.2010.0071.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kim, S., Esquivel, G. B. (2011). Adolescent spirituality and resilience: Theory, research, and educational practices. Psychology in the Schools, 48(7), 755–765. DOI 10.1002/pits.20582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Womble, M. N., Labbé, E. E., Cochran, C. R. (2013). Spirituality and personality: Understanding their relationship to health resilience. Psychological Reports, 112(3), 706–715. DOI 10.2466/02.07.PR0.112.3.706-715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Reutter, K. K., Bigatti, S. M. (2014). Religiosity and spirituality as resiliency resources: Moderation, mediation, or moderated mediation?. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 53(1), 56–72. DOI 10.1111/jssr.12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hourani, L. L., Williams, J., Forman-Hoffman, V., Lane, M. E., Weimer, B. et al. (2012). Influence of spirituality on depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidality in active duty military personnel. Depression Research and Treatment, 2012, 1–9. DOI 10.1155/2012/425463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Khan, Z. H., Watson, P. J., Chen, Z. (2016). Muslim spirituality, religious coping, and reactions to terrorism among Pakistani university students. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(6), 2086–2098. DOI 10.1007/s10943-016-0263-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Young, J. S., Cashwell, C. S., Shcherbakova, J. (2000). The moderating relationship of spirituality on negative life events and psychological adjustment. Counseling and Values, 45(1), 49–57. DOI 10.1002/j.2161-007x.2000.tb00182.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kim, Y., Seidlitz, L. (2002). Spirituality moderates the effect of stress on emotional and physical adjustment. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(8), 1377–1390. DOI 10.1016/s0191-8869(01)00128-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Koenig, H. G. (2010). Spirituality and mental health. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 7(2), 116–122. DOI 10.1002/aps.239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Hiew, C. C., Mori, T., Shimizu, M., Tominaga, M. (2000). Measurement of resilience development: Preliminary results with a state-trait resilience inventory. Journal of Learning and Curriculum Development, 1, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

45. Roberti, J. W., Harrington, L. N., Storch, E. A. (2006). Further psychometric support for the 10-item version of the perceived stress scale. Journal of College Counseling, 9(2), 135–147. DOI 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2006.tb00100.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. DOI 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sinclair, S. J., LoCicero, A. (2007). Fearing future terrorism: Development, validation, and psychometric testing of the terrorism catastrophizing scale (TCS). Traumatology, 13(4), 75. DOI 10.1177/1534765607309962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |