Mental Health Promotion

| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.015526

ARTICLE

The Essence of Accommodating Older Adults into the Social Care Sector in Malaysia

1Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, 43400, Malaysia

2Malaysian Research Institute on Ageing, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, 43400, Malaysia

*Corresponding Author: Halimatus Sakdiah Minhat. Email: halimatus@upm.edu.my

Received: 04 January 2021; Accepted: 21 March 2021

Abstract: Population ageing puts pressure on the workforce and increase the demands for aged workforce. The demographic shifts have made the issue of healthier workers, especially those of advanced age and physically related job scopes, a fundamental aspect to employing older workers. Hence, this study aimed to explore the best practices to employ older adults into the social care sector. The social care sector was chosen in view of the nature of job and declining demand among younger workers. A qualitative study was conducted involving series of focus group discussions (FGD) with social care workers of long-term care centers in the peninsular Malaysia. Data was collected using a validated and pre-tested semi-structured interview protocol. Each focus group discussions and in-depth interviews were lasted between 45 min to 1 h. A total of 57 workers were consented for the study which was divided into young and old workers based on the mean age of 41.43 [SD ± 9.97] years old. The content of the interviews was transcribed verbatim and thematic analysis was performed to inductively identify the coding and themes within the data related to the challenges employing older workers into the social care sector. Three categories of coding were identified (individual, environmental and management factors), leading to the identification of two important themes which are healthy workplace and work autonomy. The findings indicate the needs for work culture transformations to cultivate healthy working environment and freedom of speech particularly among the older workers.

Keywords: Best practice; social care; caregiver; older workers; Malaysia

Population ageing is set to intensify in the coming decades, raising concerns about demand for care, health and financial resources. The unpaid care delivered by adult children of older people was unlikely to keep up with demand and although more spouses care for partners in old age, many were likely to be living with disabilities themselves. Additionally, the extension of the retirement age would reduce the pool of informal and unpaid carers.

Social care needs of older people are driven by their inability to self-care and live independently, most often assessed by needing help to undertake one or more basic activities of daily living (ADLs) such as bathing, dressing, or toileting [1]. Although integrated care would be ideal for older persons, medical and social cares are being serve separately in some countries including the UK and Malaysia. This indirectly created issue related to scope of jobs of a social carer as medical problems become commoner among the extreme age groups and quite often, they require both at the same time.

The increasing demand of care workforce with appropriate skill will be a challenge for an ageing country in order to tailor the needs of increasing ageing population [2]. This suggests that retaining aged care workers for economic and quality of care reasons will be of greater significance in the future [3]. Care workers shortage in residential aged care has been reported in country with similar situation including United Kingdom and Australia [2]. Research has reported that the shortage among care workers were influenced by barriers and challenges that come together with the job [3].

Various issues have been reported that is affecting the quality of care provided and work satisfaction among the carers. Being a care worker bring challenges to the individuals in term of physical, environment and emotional [4]. Employment characteristics and organizational resources such as low salary, unsuitable working environment, heavy workload and poor career development has been reported as the challenges and barrier that influenced the turnover among the care workers [5–8]. In addition, care work also been reported to be socially underappreciated [9]. All these have been reported to be connected to turnover of care workers in aged care workforce [2,10].

Care worker high turnover can be costly on nursing homes and also linked to poor quality of care [11]. Annually, care worker turnover has been reported to as high as 71% and 40% of them were estimated to leave the workforce [12]. Research has found that workers tend to loyal to their job if they are satisfied of what they are doing. The connection between the job satisfaction and turnover rate has been reported especially in nursing home [13]. Additionally, managerial support was shown to be indirectly associated with workers job satisfaction. In other word, how managers practice in workplace also ease workers’ barriers and challenge in workplace which result in better satisfaction [13].

Malaysia is experiencing rapid ageing and expected to become an aged nation with 15% of population will be those of 65 years old and above in 2030. Social work in Malaysia is synonym social welfare and is not in line with most social work departments in advanced countries. The common understanding of social welfare in Malaysia is of a department that assists people with charity and provides care for the elderly, orphanages or care for victims of natural disasters such as floods.

Compared to developed countries such as the UK and Japan, Malaysia is yet to experience shortages of social care workers for older persons. However, the sector is becoming less attractive especially among the younger age group due to the low salary despite its perceived heavy workload. Despite all the barriers and challenge in social care work, certain attractors might overcome the limitations. The need of identifying and implementing the best practice in social work is crucial in attracting care workers to stay in the workforce. In addition, positive aspect of residential aged care work is understudied [14] especially in Malaysia. Thus, the current study aimed to explore the best practices to deal with challenges in the social care sector in order to accommodate the aged workforce into the sector in Malaysia.

This was a qualitative study aiming to explore the challenges faced by the care workers in the social care sectors. The findings presented in this paper is part of a collaborative project between a local university in Malaysia and the United Kingdom on best practices to employ older workers in the social care sector.

The data was collected at four welfare-based social care homes for older persons which are fully subsidized by the government and managed by the Department of Social Welfare Malaysia. Each of the centers representing a zone in the peninsular Malaysia namely, the north, south, middle and east zones.

A total 57 social care workers were conveniently identified at the selected centers and were divided into two age categories based on the mean age. Separate focus group discussions were conducted according to these two age categories. Staff were identified and selected by the manager at the individual center which was approached via letter, email and telephone calls. They were categorized into young and old workers based on the mean age.

Focus group discussion was used as method of data collection. Each focus group discussion was conducted in a quiet room with two concurrent sessions, lasted for 45 to 60 min each and contain between 5 to 10 participants. The discussions were professionally facilitated by experienced university or higher education tutors/lecturers/research officers with structured, pre-prepared questions following an agreed protocol, but with flexibility given to the presenters to deviate from the protocol and follow interesting leads. All workshops and interviews were audio recorded. The discussions were structured around a set of root questions covering subjects’ experience and understanding about working as a social carer/caregiver—“What do understand about working as a social carer or caregiver?”, Have you faced any problems (physically or mentally) while working as a caregiver?”, “What do you think can be done to improve to working nature of a caregiver?”, “Do you think this sector/job is suitable for senior/aged workers?”. Each root question was followed by a number of probe questions to flesh out detail in subjects’ responses. The focus discussions were discontinued once saturation point was reached, with little or no new information produced to address the research questions.

The data were anonymous and code numbers allocated to each case. Approval from the Department of Social Welfare Malaysia was obtained prior to data collection. Individual informed consent was also obtained on the day of data collection from all the participants with the purpose of the research and the condition of anonymity, the right to opt out and opportunities to correct any inaccurate statements attributed to them were explained beforehand. Appropriate standards for ethical research were adhered to throughout the project. In view of some related sensitivity aspects of the topics being explored, participants were also provided with writing material for them to address any uncomfortable issues to be discussed openly.

Inductive thematic analysis was performed to identify the codes and themes within the data. This approach utilizes five related steps of: familiarization, coding, theme development, defining themes and reporting [15]. During the process of familiarization, all interview data were reviewed and all sections of the interviews relating to issues, challenges, perceptions and responses towards ageing workforces in the social care sectors were extracted. Emergent themes were identified from the data, defined and reported through an iterative process of theme development. Specialist software was not used with the primary data coder was HSM. To address issues of analytical rigor and trustworthiness, a subset of transcripts were double-coded by an external researcher with well experience in qualitative research. The analysis was further tested and discussed during meetings with the rest of the research team, including the moderators, rapporteurs, and also the co-researcher.

3.1 Background of the Participants

Total of 8 focus group discussions were conducted with 57 social care workers which were predominantly Malay participants. The mean age and working duration were 41.43 [SD ± 9.97] years old and 15.70 [SD ± 10.05] years, respectively. There was almost equal distribution of carers between the two age groups and according to gender, with 29 participants aged less than 40 years old and 28 aged 40 years old and above and also 28 female and 29 male carers.

3.2 Challenges to Employing Older Workers as Social Caregivers

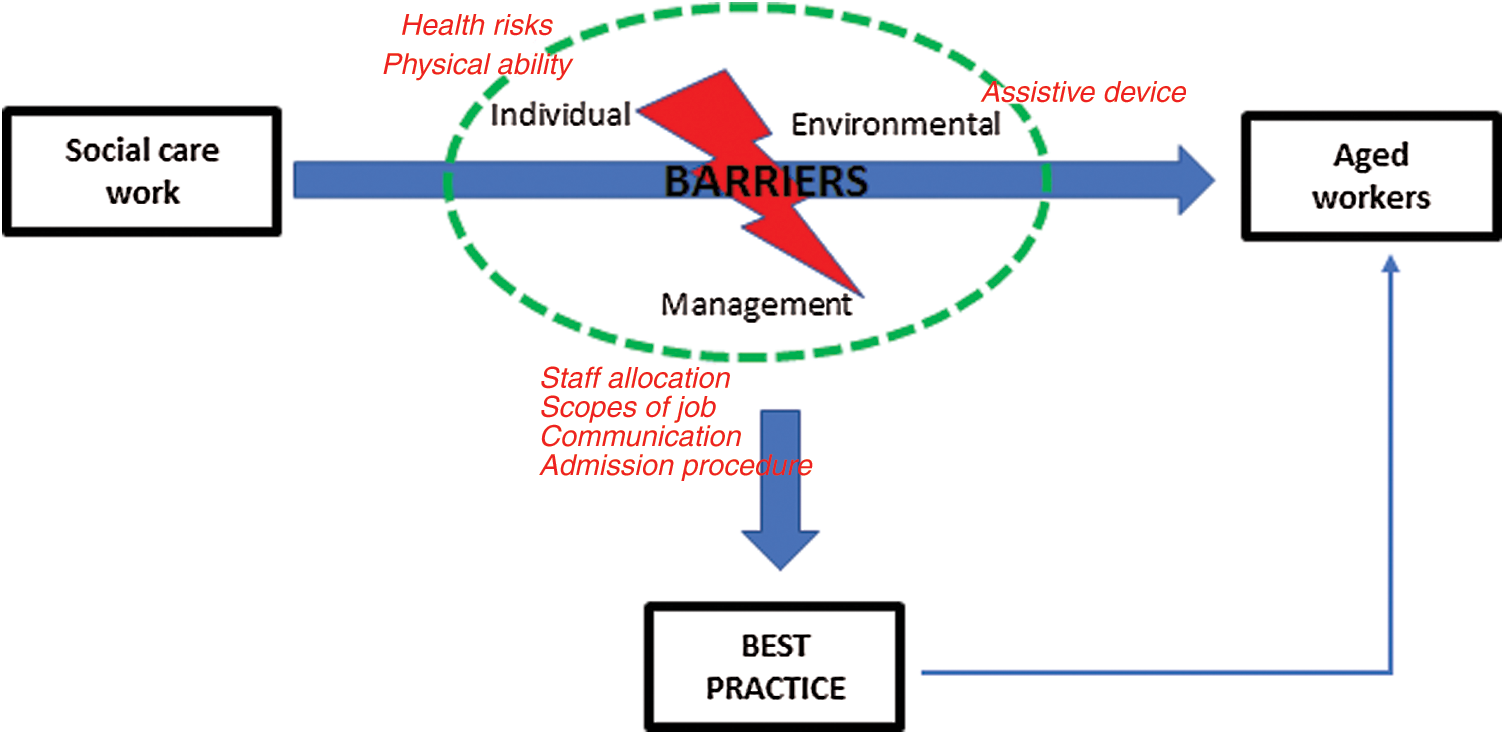

Similar coding related to challenges as social care workers were identified in both, the old and young age group which were categorized into individual, environmental and management factors as summarized in Fig. 1 below.

Figure 1: Summary of challenges as social care workers

Majority of the participants were aware of the potential health risks they were expose to, physically and mentally. These include chronic back pain from lifting and moving clients particularly those of bed ridden, risks towards infectious diseases with scabies being the commonest and also burnout, mental fatigue and stress. Some were also reported exposure towards highly infectious and deadly diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV. Emphasis was also given towards reduced physical ability and workability with increasing age of the social caregivers which may further increase the risk exposure.

As for the environmental factors, the main issue discussed was in relation to not only the absence of assistive devices but also inadequacy of some basic equipment to assist them conducting the daily tasks. These include the availability of adjustable bed and wheelchair and equipment to move the clients from one bed to another. Although the issue was overcome by specific maneuver conducted manually, majority were experiencing lower back pain, ranging from mild to severe which directly further increase the negative impact on their work productive.

The factors related to management were among the major dissatisfaction among the caregivers. These include allocation of staff to client ratio, the scopes of job in which they described it as “unexpected job scopes…”, “not just social care work…”, perceived poor communication between the caregivers and managers reflecting the element of work autonomy and perceived poor admission procedure for the clients or standard of procedure (SOP) which directly put them at various risks. In view of the potential health risks they are expose to and vague definition of the job scopes, they demand entitlement for “critical allowance” which has been enforced among hospital-based caregivers.

Based on the challenges identified two themes were emerged to reflect the best practices to employing older workers as formal social caregivers which are healthy workplace and work autonomy. The healthy workplace theme is related to the health risks (mental and physical) originated from the nature of the work and absence of appropriate equipment or assistive devices, programs to reduce mental health related risks and the work culture (organization and management). Meanwhile, work autonomy was more related to the management factors, and is referring to the freedom of speech to express ideas and at the same time as a platform for a better communication foundation between workers, managers and administrative staffs. Both themes need to be addressed accordingly to accommodate the diverse needs of aged workers.

The rapid increase of ageing population experienced globally creating a high demand in the long term care services. In the United States, 25% of older people live in institutions such as nursing homes and other residential facilities and the number of older people requiring long-term care services is projected to be nineteen million by 2050 [16]. Unfortunately, there may not be enough resources to accommodate the high demand, which triggers future consideration to employ older adults into the sector.

Currently, In Malaysia, the government and welfare agencies play a key role in providing services to older people, especially through the residential care institutions [17]. Welfare-based residential care services in long term care institutions are managed and regulated by the Department of Social Welfare for the purpose of caring and protecting older people with the services of basic needs, health care, counselling, recreation and religious activity. This study has identified two main best practices related to recruitment of older adults into the social care sectors, based on the reported challenges. In view of the welfare nature of the centers involved in this study, such challenges are expected due to limited resources and massive influx of older persons into the centers.

Care refers to the act of assisting another person’s fundamental needs and/or nursing [18]. It often requires attention to the physical, psychological, social, and well-being of both the caregivers and the people requiring care. In residential care facilities, most of the work are carried by the care workers including assisting in daily needs activities, housekeeping, providing meal, and distributing medication [19]. As a direct care worker, they play an important role in the provision of long-term care [20]. However, job dissatisfaction reported to be the turnover predictors for the care workers [21] due to the related burden of the care work, and poor employment conditions [22].

There has been a massive literature on caregiving burden, particularly its impact on health of the caregivers. A study identifying the impact of caregiving on health and quality of life (QOL) among primary informal caregivers (PCGs) of older persons in Hong Kong reported significant increased risks for reporting worse health, more doctor visits, anxiety and depression, and weight loss among the PCGs [23]. High caregiver burden score (Zarit Burden Scale) was positively associated with adverse physical and psychological health and poorer QOL particularly among female PCGs. Meanwhile, another similar study in Karachi, Pakistan revealed 48% of the caregivers claimed caregiving has an overall negative impact on various aspects, such as physical (40.8%), psychological (47.8%), and professional aspects (51.8%) of their lives due to extensive demands of caregiving and limited resources [24] reflecting the need to a healthier working environment.

The concept of healthy workplace is not new, but it has indeed changed, evolving from a nearly exclusive focus on occupational health and safety (managing the physical, chemical, biological, and ergonomic hazards of the workplace) to include work organization, workplace culture, lifestyle, and the community, all of which can profoundly influence worker health [25]. World Health Organization defined healthy workplace as one in which workers and managers collaborate to use a continual improvement process to protect and promote the health, safety and well-being of all workers [26]. The sustainability of the workplace involves health and safety concerns in the physical work environment, health, safety and well-being concerns in the psychosocial work environment (including organization of work and workplace culture), personal health resources in the workplace; and ways of participating in the community to improve the health of workers, their families and other members of the community [27].

Workers who are in job conditions that combine high demands, low control, and low support are at the highest risk for psychological disorder [28]. It is generally agreed that supportive working conditions help workers to cope with job stress and consequently cause workers to feel a sense of attachment to their current organization [29]. A proper policy needs to be developed, specifying the nature and scopes of jobs that are expected for older workers, including the job modifications if we were to consider employing older adults as caregivers. This is to ensure that, the health impact is lesser since they are at higher risk compared to younger workers.

On the other hand, autonomy is one of the essential elements in building true employee engagement and also one of several core job design characteristics that theorists and researchers have used in order to predict and test the relationships between job design and desired work outcomes [30]. In the workplace, autonomy refers to the degree of freedom employees have while working through power to shape the work environment in ways that allow the employees to perform at their best. Cano et al. [31] found that work autonomy was the most motivating aspect for universities faculty member job satisfaction and highlighted that ‘work itself’ was the characteristic most satisfying, and ‘working conditions’ being the least satisfying characteristic of their jobs. Increased autonomy at work has also been linked with an increase in job satisfaction [32]. Taking into consideration the possibility on hiring retired older adults with diverse experiences and skills into the social care sector, work autonomy is a crucial component need to be considered in order to ensure effective communication, healthier working environment and also serve as a tool to identifying the unseen needs of older workers.

The findings of this study emphasizing two main elements need to be considered in order to employ older adults as caregivers which are, healthy workplace and work autonomy. Policy and program initiatives related to healthy workplace and work autonomy should be in place before employing older workers to ensure the safety and productivity of the older workers without compromising their health.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the respondents, fieldworkers, co-researchers and local authorities involved in this study.

Funding Statement: The project was supported by the Newton Advanced Fellowship Scheme which was funded by the Academy of Science Malaysia and British Academy [Grant No. AF160205].

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Andrews, J., Manthorpe, J., Watson, R. (2005). Employment transitions for older nurses: A qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 51(3), 298–306. [Google Scholar]

2. Chenoweth, L., Merlyn, T., Jeon, Y. H., Tait, F., Duffield, C. (2014). Attracting and retaining qualified nurses in aged and dementia care: Outcomes from an Australian study. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(2), 234–247. [Google Scholar]

3. Karantzas, G. C., Mellor, D., McCabe, M. P., Davison, T. E., Beaton, P. et al. (2012). Intentions to quit work among care staff working in the aged care sector. Gerontologist, 52(4), 506–516. [Google Scholar]

4. Fillion, L., Tremblay, I., Truchon, M., Côté, D., Struthers, C. W. et al. (2007). Job satisfaction and emotional distress among nurses providing palliative care: Empirical evidence for an integrative occupational stress-model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

5. Castle, N. G., Degenholtz, H., Rosen, J. (2006). Determinants of staff job satisfaction of caregivers in two nursing homes in Pennsylvania. BMC Health Services Research, 6, 60. DOI 10.1186/1472-6963-6-60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. DeForge, R., van Wyk, P.,Hall, J., Salmoni, A. (2011). Afraid to care; unable to care: A critical ethnography within a long-term care home. Journal of Aging Studies, 25(4), 415–426. [Google Scholar]

7. Rigby, J., O’Connor, M. (2012). Retaining older staff members in care homes and hospices in England and Australia: The impact of environment. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 18(5), 235–239. [Google Scholar]

8. Tuckett, A., Parker, D., Eley, R. M., Hegney, D. (2009). ‘I love nursing, but.’—qualitative findings from Australian aged-care nurses about their intrinsic, extrinsic and social work values. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 4(4), 307–317. [Google Scholar]

9. Holroyd, A., Dahlke, S., Fehr, C., Jung, P., Hunter, A. (2009). Attitudes toward aging: Implications for a caring profession. Journal of Nursing Education, 48(7), 374–380. [Google Scholar]

10. Mallidou, A. A., Cummings, G. G., Schalm, C., Estabrooks, C. A. (2013). Health care aides use of time in a residential long-term care unit: A time and motion study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(9), 1229–1239. [Google Scholar]

11. Seavey, D. (2004). The cost of frontline turnover in long-term care. Washington, DC: Better Jobs Better Care. [Google Scholar]

12. Smith, K., Baughman, R. (2007). Caring for America’s aging population: A profile of the direct-care workforce. Monthly Labor Review, 130(9), 20–26. [Google Scholar]

13. Bishop, C. E., Squillace, M. R., Meagher, J., Anderson, W. L., Wiener, J. M. (2009). Nursing home work practices and nursing assistants’ job satisfaction. Gerontologist, 49(5), 611–622. [Google Scholar]

14. Gao, F., Tilse, C., Wilson, J., Tuckett, A., Newcombe, P. (2015). Perceptions and employment intentions among aged care nurses and nursing assistants from diverse cultural backgrounds: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Aging Studies, 35, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

15. Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

16. US Department of Health and Human Services (2003). The future supply of long-term care workers in relation to the aging baby boom generation: Report to congress. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/future-supply-long-term-care-workers-relation-aging-baby-boom-generation. [Google Scholar]

17. Rashid, S. N. S. A. (2013). Planning a barrier free environment and better quality of life based on the predictors of out-of-home activities of rural older Malaysians. International Review of Social Sciences and Humanities, 5(1), 20–29. [Google Scholar]

18. Ball, J., Ballinger, C., de Iongh, A., Dall’Ora, C., Crowe, S. et al. (2016). Determining priorities for research to improve fundamental care on hospital wards. Research Involvement and Engagement, 2(1), 31. [Google Scholar]

19. Henderson, J. N. (1994). Bed, body, and soul: The job of the nursing home aide. Generations, 18, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

20. Graf, E., Zimmermann, K., Zúñiga, F., Cignacco, E. (2015). Affective organizational commitment in Swiss nursing homes: A cross-sectional study. Gerontologist, 56(6), 1124–1137. [Google Scholar]

21. Timmreck, T. C. (2001). Managing motivation and developing job satisfaction in the health care work environment. The Health Care Manager, 20(1), 42–58. [Google Scholar]

22. Bohle, P., Pitts, C., Quinlan, M. (2010). Time to call it quits? The safety and health of older workers. International Journal of Health Services, 40(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar]

23. Dhaini, S. R., Zúñiga, F., Ausserhofer, D., Simon, M., Kunz, R. et al. (2016). Care workers health in Swiss nursing homes and its association with psychosocial work environment: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 53, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

24. Irfan, B., Irfan, O., Ansari, A., Qidwai, W., Nanji, K. (2017). Impact of caregiving on various aspects of the lives of caregivers. Cureus, 9(5), e1213. [Google Scholar]

25. Burton, J. (2016). WHO healthy workplace framework and model: Background and supporting literature and practices. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Headquarters [Google Scholar]

26. World Health Organization (2020). Healthy Workplaces: A WHO Global Model for Action.https://www.who.int/occupational_health/healthy_workplaces/en/. [Google Scholar]

27. Hebert, D., Lindsay, M. P., McIntyre, A., Kirton, A., Rumney, P. G. et al. (2016). Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: Stroke rehabilitation practice guidelines, update 2015. International Journal of Stroke, 11(4), 459–484. [Google Scholar]

28. Kim, H., Stoner, M. (2008). Burnout and turnover intention among social workers: Effects of role stress, job autonomy and social support. Administration in Social Work, 32(3), 5–25. [Google Scholar]

29. Dollard, M. F., Winefield, H. R., Winefield, A. H., de Jonge, J. (2000). Psychosocial job strain and productivity in human service workers: A test of the demand-control-support model. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(4), 501–510. [Google Scholar]

30. Sadler-Smith, E., El-Kot, G., Leat, M. (2003). Differentiating work autonomy facets in a non-Western context. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(6), 709–731. [Google Scholar]

31. Cano, J., Castillo, J. (2004). Factors explaining job satisfaction among faculty. Journal of Agricultural Education, 45(3), 65–74. [Google Scholar]

32. Amarasena, T., Ajward, A., Ahasanul Haque, A. (2015). The effects of demographic factors on job satisfaction of university faculty members in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Academic Research and Reflection, 3(4), 89–106. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |