Mental Health Promotion

| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.015759

ARTICLE

Goal Self-Concordance Model: What Have We Learned and Where are We Going

1Business School, Hohai University, Nanjing, 210098, China

2School of Business Administration, Nanjing University of Finance and Economics, Nanjing, 210023, China

3College of Computer and Information, Hohai University, Nanjing, 210098, China

*Corresponding Author: Ting Wen. Email: wen5ting@163.com

Received: 11 January 2020; Accepted: 15 March 2021

Abstract: Goal self-concordance reflects self-generated personal goals aligning with people’s interests and core values in one’s implicit personality as organic components, which is measured by the “perceived locus of causality” PLOC. Pursuing and achieving self-concordant goals both predict diversified outcomes in need-satisfaction, mental and physical well-being, positive attitude and behavior, etc. Based on expounding and sorting out the concept and measurement about goal self-concordance, the author analyzes the differences among a series of goal self-concordance theories. This paper focuses on the latest research trends and summarizes five influencing aspects of goal self-concordance: mental health, cognition, emotion, personal will, and behavioral outcomes. The mediating effects are discussed concerning antecedents and influence effects, the influence effects are shown in three aspects including the characteristics of individual, target, and environment. While the antecedent effects are respectively reflected in self-insight, personality, empowerment, and self-supported environment, content, and context of the goal itself. Finally, the author proposes several potential research interests from a broader perspective based on the current literature.

Keywords: Goal self-concordance; concept; measurement; antecedents and consequences (research status); future research prospects

Many pieces of literature have introduced the potential of positive changes and outcomes brought by personal goal pursuit [1–3]. Earlier studies also assumed that goals serve as an embodiment of people’s values and beliefs, which highlights the process and results of goals-pursuit for the individuals. However, the reality tells that those goals of “self” that cannot reflect individual interests or internal value demand are less possible to be achieved. They contribute less to obtain happiness even when they are realized [4–6]. The extended model of goal setting theory also agrees with that people’s commitment to the goal will be strengthened when they believe that their goal can be achieved and the goal is of great significance, the goal performance will be improved [7,8]. Self-determination theory explains that the goal-pursuit, which reflect individual interests and internal values and beliefs, as well as meet the basic psychological demand of individuals, does help to improve their sense of happiness. DeCharms [9] further explored the motivations of goal-choosing and the relationship between goals and basic psychological demands. It was released that goals that are highly consistent with individual interests and intrinsic value beliefs (self) are more incline to create happiness. The degree of consistency between individual goals and “self” reflects the motivation of individual. Sheldon et al. [4] proposed the concept of goal self-concordance model (SCM) based on self-determination theory.

Considering that there are certain literature on goal self-concordance, the author focuses on the further collation of the influencing factors of goal self-concordance (i.e., antecedent variables), and systematically sorts out the influence effect of goal self-concordance, as well as provide some perspectives for the later researches.

2 Relationship and Difference between Goal Self-Concordance Model and Its Related Theories

2.1 Concept and Measurement of Goal Self-Concordance Model

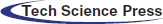

The goal self-concordance model (SCM) proposed by Sheldon et al. [4] refers to the integrated degree between the goals of individuals and their internal interests or values. These internal values and interests also act as the organic components of “self”, an active and motivative “self”. Goal SCM also reflects the integrated degree of motivation in the perceived locus of causality (PLOC) [9]. Sheldon et al. [4] found that a higher score of goal self-concordance may lead to autonomous motivation. When pursuing goals, more positive emotions and higher satisfaction may also create more will of one’s efforts, which accordingly makes it easier to achieve goals. Meanwhile, those attainments are closely relative to the intense need for satisfying experiences involving autonomy, competence, and relationship in daily life. Increasing need satisfaction over time tends to produce better overall well-being. Therefore, when goal and self are highly integrated and consistent, goal achievement may have special predictive effects on need satisfaction, positive attitude, and behavior outcomes [4], as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The self-concordance model

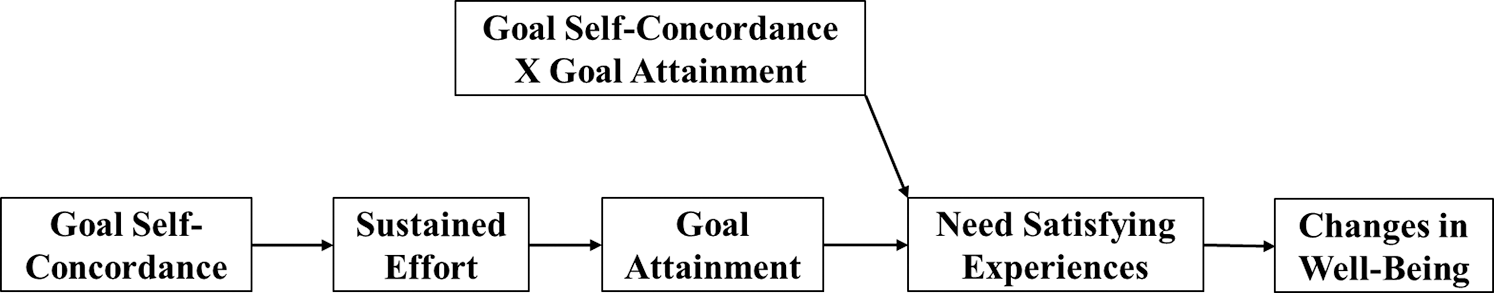

Goal self-concordance is operationally defined as measuring the difference between the perceived locus of causality (PLOC) of one’s goal and struggle [10]. Since autonomy-oriented (identification and internal) motivation and control-oriented (external and introjection) motivation are considered concurrently, it reflects the integrated degree of individual motivation in PLOC, and further reflects the integrated degree of goal and self in concerning personality, namely, level of goal self-concordance, goal self-concordance or goal self-unconcordance (Fig. 2). Different from the previous researches on self-determination theory, it focuses on the goal given by individual speech or expression, and the personal action constructs (PAC) unit is adopted in the research of motivation psychology in terms of methodology. Sheldon names it as a goal methodology of the special law of motivation research (Idiographic Goal Methodology).

Current literature provides three methods to measure self-concordance. Sheldon et al. [4] mentioned one of them in their paper “goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: the self-consistency model”. The measurement of goal self-concordance is implemented as follows: first, the subjects are requested to write down 5–15 goals that they are pursuing or setting, and then classify the degree of motivation internalization according to self-determination theory, namely, external adjustment, introjection adjustment, identity adjustment, and internal adjustment. Controlled reasons included “because somebody else wants you to, or because you’ll get something from someone if you do” (external) and “because you would feel ashamed if you did not—you feel that you should try to accomplish this goal” (introjected). Autonomous reasons included “because you believe it is an important goal to have” (identified), “because of the fun and enjoyment which the goal will provide you—the primary reason is simply your interest in the experience itself” (intrinsic), Items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all for this reason) to 7 or 9 (completely for this reason) [4,11], a measure of goal self-concordance was calculated by subtracting the average of the controlled items from the average of the autonomous items for each goal, an overall score of goal self-concordance was calculated by taking the average of the self-concordant scores across all goals. A positive difference indicates a concordance between goal and self, and a higher value is positive relative to a higher level of goal self-concordance. While negative difference refers to goal self-unconcordance, and higher value also indicates a higher level of goal self-unconcordance. There is no report or research on zero difference so far since there are too few cases. The second measurement is similar, except that the integrated motivation is also included in the autonomous motivation, for example, it is stated as “because it represents who you are and reflects what you value most in life” (integrated), this expression will be later evaluated [12,13]. Deci et al. [14] scale is adopted as the third method. The statements such as “You choose this goal because somebody else wants you to or because the situation demands it” and “You pursue this goal because you would feel anxious, guilty, or ashamed if you did not” (external and introjected items represent controlled motivation, each of these checked adjectives was given a value of −1); “You pursue this goal because you believe it’s an important goal to have” and “You pursue this goal because of the fun and enjoyment it provides you” (identified and intrinsic items represent autonomous motivation, each of these checked adjectives was given a value of +1). The values were then summed to calculate goal self-concordance [15]. Considering the score of each goal on each motivation at the same time, the author found the first and second methods are more specific and detailed. However, someone may have some concerns on this way of measurement, they hold the opinion that people who score low on two kinds of motivation may also get the same score of goal self-concordance. One argument in defense of this measurement is that the “quantity” (sum) of motivation may differ in both cases, while the “quality” (difference) is accurately measured instead. Therefore, researchers may choose qualitative or quantitative measures according to varied research objectives, or check the sum of the scores of autonomy-oriented and control-oriented motivation and the differences between them [16]. Additionally, some scholars have misunderstood the measurement of goal self-concordance as for the measurement methods in the published studies. The author hopes a fine trace back being well conducted to the source in this review.

Figure 2: The PLOC description scheme of goals

2.2 The Relationship and Difference between Goal Self-Concordance Model and Related Theories

The study of self-decision theory (SDT) begins with the internalization of external motivation [14]. With the progress of related researches, it then focused on the impacts of different social situations (such as work, school, sports, etc.) on the process of motivation and the reaction of individuals. It also attaches importance to the intermediary function of basic psychological demands (autonomy, competence, relationship) in the interaction between social environment and individuals, six sub-theories are hereby developed. The goal content theory [17], which is included as a sub theory of self-determination theory, focuses on the effects of different types of goals with varied demands on the basic psychological needs of individuals. For instance, the achievement or acquisition of internal goals (personal progress and intimacy) may enhance one’s sense of happiness. However, external goals (economy, reputation, etc.) make less promotion to the sense of happiness for the reason external goals cannot directly meet the basic psychological demands of individuals and sometimes may even damage it. The goal SCM is rooted in the self-determination theory, but there are some differences between them. It is developed based on goal setting and studies the motivation process behind the goal generation and the intention process to achieve the goal according to the goal generated by the individual initiative. There are also some connections, self-determination theory applies PLOC to the study of itself, and Sheldon et al. [18] apply PLOC to the researches of self-generated personal goals. When it comes to the differences, self-determination theory follows closely with the continuity and quality of motivation, while the goal SCM pays more attention to the attribution of goal-choice, namely the impacts of motivation level of goal (which reflects the self-integrated degree of interest between goal and internal stability, core values, etc.) on attitude and behavior results. Goal self-concordance acts as a part of self-integration, which originates from the demands of one’s internal interest and self-identity. It emphasizes the initiative of one’s advance and integration by making researches on the goal itself and the process of pursuit, and a high level of goal self-concordance can also predict positive attitude and behavior.

In 1967, E. A. Locke, a professor of management and psychology at the University of Maryland, proposed the theory of goal-setting. He believes that the goal itself has the function of motivation, which transforms one’s demands into motivation and behavior, and finally achieves his or her goal by comparing one’s behavior results with the goal or adjusting them at any time. External stimulus (reward, work feedback, supervision, etc.) affects performance through achieving goals. Goals can guide one’s activities and lead to goal-related behaviors, which helps to adjust one’s efforts according to the difficulty of goals and affect the persistence of individual behaviors. Locke’s et al. [19] research did not follow the relationship between goal setting and task motivation until 2002. Ryan [20] proposed that “human behavior is influenced by conscious goals, plans, intentions, tasks, and preferences”. Many scholars have also further studied the relationship between goal and task performance based on Ryan’s view that “conscious goal affects behavior”. Bandura et al. [8] found that reasonably designated goals (goals are attractive and likely to be achieved) tend to show the same effect of excitation, which is more effective than simply setting goals without considering rationality. Hirt et al. [21] discovered that one’s sense of self-efficacy can be strengthened when he or she believes that the goal with great significance can be achieved. The theory of goal-setting has been emphasizing the incentive effect of goal, it adjusts one’s behavior according to the difficulty of goal and specific target [22]. Therefore, it pays more attention to the incentive function of goal and the effect of goal achievement. Although the goal SCM is also developed based on goal setting, it does not follow the intrinsic incentive effect of goals. Instead, it reflects the motivation level of individuals on PLOC by measuring the degree of self-concordance between self-generated goal and self. To sum it up, the goal SCM focuses on the motivation level of goal, the integrated degree between goal and self, as well as the positive psychological effects and behavioral outcomes when goal self-concordance occurs.

In short, the measurement of goal self-concordance on PLOC not merely provides a significant path to approach positive motivation, but introduces means to understand some difficult humanistic concepts, such as “authenticity” and “true self”. To conduct a measuring process when maintaining the authenticity of individual meaning, some studies applied longitudinal modeling technique and causal modeling technique to prove how the two-cycle “upward spiral” model is crucial to one’s health and development. Therefore, these researches not only promote the development of positive psychology but enhance the vitality of humanistic theory.

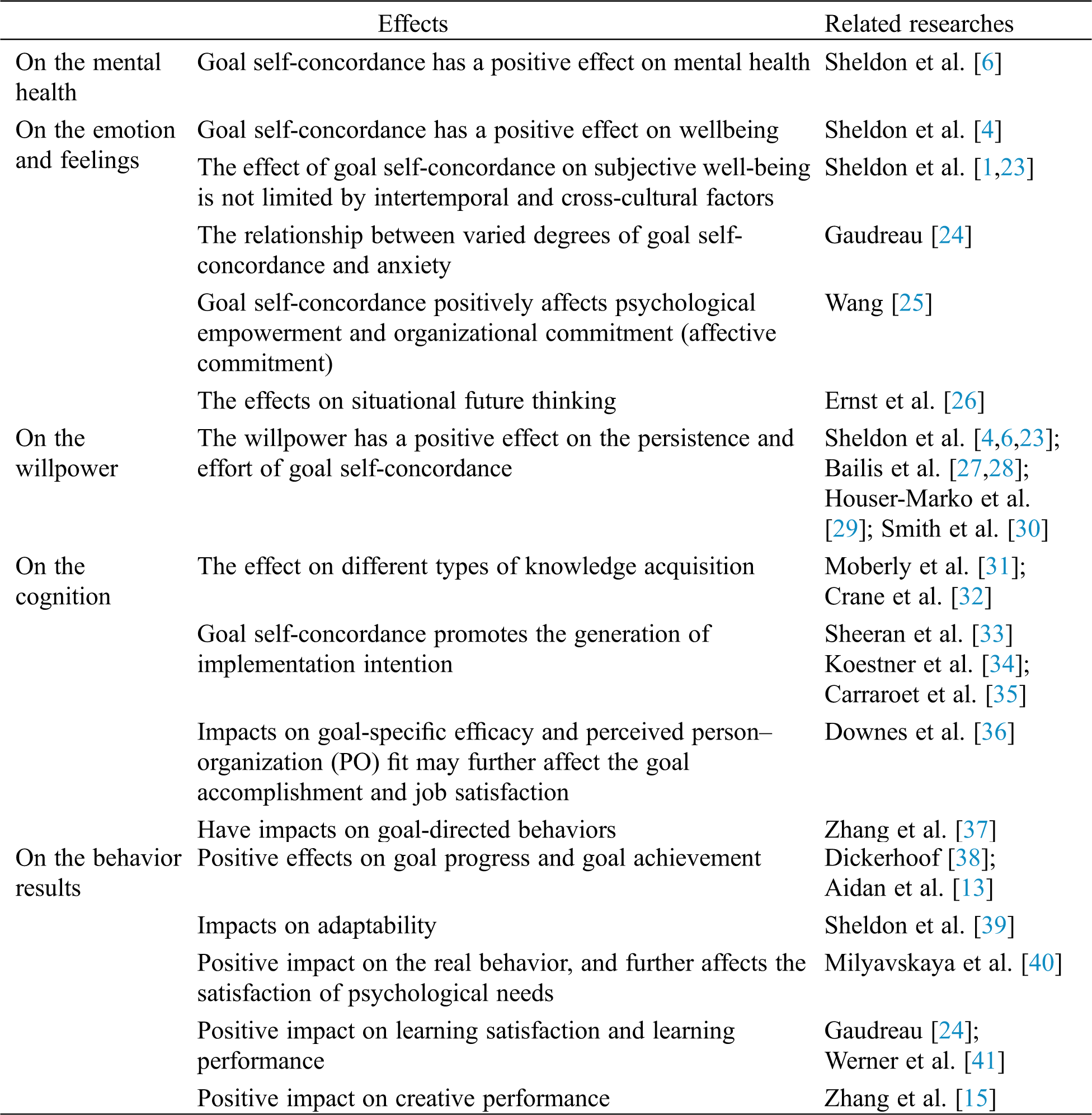

3.1 The Effect of Goal Self-Concordance

Someone may view their goals less significantly, they tend to gain what they want and produce a sense of competence or avoid the feeling of helplessness during the process of achieving an obscure objective. However, the goal SCM has demonstrated the relationships among one’s choice of goals. Some goals are more conducive to people’s mental health, happiness or self-realization than the others since they better represent one’s fundamental interests, values, talents, demands and motivations. On the contrary, people may uselessly spend time and energy on approaching the possible future when choose a “wrong” goal. In this case, one’s potential may not be well displayed even if this goal is finally achieved. Even worse, the result may be meaningless or even harmful, then such kind of unconcordance between goal and self may transform into a major obstacle to the development of personality. Some scholars have also realized that goal self-concordance and the achievement of it may spread special predictive effect on need satisfaction, sense of happiness, positive attitudes and behavior results. Therefore, they’ve carried out research on the effect of goal self-concordance from varied perspectives and for different research objects. In this paper, those researches are divided into five categories, that is, the impact on mental health, emotion and feelings, willpower, cognition and results (see Tab. 1).

Table 1: Related researches on the effects of goal SCM

3.1.1 The Impacts on the Level of Mental Health

According to the self-determination theory, the level of motivation is closely relative to the mental health of individuals. Those with a higher level of autonomous motivation tend to promote mental health. Sheldon et al. [5] found that individuals with higher goal self-concordance may acquire higher level of mental health.

3.1.2 The Impacts on Emotions and Feelings

Sheldon and Elliot verified the positive impact of goal self-concordance on one’s sense of happiness through three studies. Two phrases are involved in the process, the first stage describes the realization of goals, and the second stage explains that the significance of goal achievement in improving the sense of happiness. Goal self-concordance is derived from one’s interest and needs of intrinsic value, which triggers to work continuously and steadily until achieving the goals. Meanwhile, the realization of self-concordant goals brings about the satisfaction of psychological needs and then produces positive results such as improved happiness. It is hereby noted that the impact of goal self-concordance on individual happiness can be intertemporal. The goal at a certain time and the efforts to pursue it helps to affect one’s satisfaction with psychological needs for a while. Meanwhile, the realization of self-concordant goals, the satisfaction of psychological needs, and the improvement of happiness will jointly lay impacts on one’s next formulation of self-concordant goal, thereby forming an upward spiral and allowing the individual to continuously acquire goals, self-integration, and self-promotion. Sheldon et al. [23] had measured the efficacy of two kinds of happiness-related exercises and they found that self-concordant goal motivation can predict a continued increase in happiness during exercising.

Sheldon et al. [1] discovered in a cross-cultural study that there is no significant difference in level of one’s goal self-concordance whether if it is conducted in a typical individualistic cultural country, such as the United States, or in a typical collectivist cultural country and region, such as mainland China, Taiwan and South Korea. In varied context of cultures, goal self-concordance may predict SWB (Subjective well-being) within every culture concerning the subjective well-being and its various dimensions. In addition, the pursuit of self-concordant goals may lead to a series of positive psychological results.

It was released in Gaudreau’s [24] study of 220 undergraduates that students with low-level of goal self-concordance may suffer from anxiety when they implement learning method-oriented goals and performance-oriented goals. The author suggests that the combined effect of content and motivation of goal should be considered.

Wang [25] had also conducted an empirical study on the relationship between goal self-concordance and psychological empowerment as well as organizational commitment. The results of researches on 273 employees of enterprises in various regions in Zhejiang showed that goal self-concordance is significantly correlated with psychological empowerment and emotional commitment. Psychological empowerment plays a mediating role in the relationship between goal self-concordance and emotional commitment. The two dimensions of psychological empowerment, namely significance of work and autonomy, play a complete mediating role between the goal self-concordance and emotional commitment.

The researches of Ernst et al. [26] illustrated that how individual goals shape the representation of future events. Goal-processing is deemed as a core component of situational future thinking, whose involved participants are asked to imagine specific future events related to each goal. According to the varied motivations of goals, the researchers distinguished between the goals of self-concordance (what they want to realize) and non-self or non-concordance (what they must achieve). The studies had released that self-concordant future events is connected with special phenomenological status: they are related to a stronger “realistic” and pre-experience of the future, and they are better integrated with autobiographical knowledge, together with more positive and stronger emotional characteristics.

3.1.3 The Impacts on Willpower

The impacts of goal self-concordance on the willpower are mainly reflected in the efforts and persistence to achieve the goals. Existing literature agree with that self-concordance goals may lead to much more sustained efforts. Everyone can write down any goals they like, however, some goals may never be achieved when they do not reflect their intrinsic motivation and stable values or interests. Sheldon et al. [4,6] also provided an earlier evidence about the sustainable incentive theory in goal self-concordance, more and more evidence has since emerged.

Bailis et al. [27] reported on their study of continuing health club members that those participants joined the health club with self-concordance goals are more likely to remain their membership in even two years later. How can this happen? Those self-concordance members are more inclined to make self-improvement rather than self-esteem (growth and health-related goals that support the assumption of the goal SCM are considered self-concordant). Additionally, those members seldom compare themselves with others, and they are also less negatively affected by the society. As far as they concerned, the membership means promotion of health, rather than just being considered looks well. Similarly, Bailis et al. [28] compared two kinds of motivational information as predictors for the later physical activity. They found that self-concordant individuals tend to remain active longer in response to the information that emphasizes health-seeking challenges, while the non-concordant individuals remained active longer in response to information that emphasized social support.

Sheldon et al. [23] measured the efficacy of two happiness-related exercises and found that those self-concordant people tend to persist longest in the exercise.

Houser-Marko et al. [29] solved the “problem of persistent excitation” in another way by introducing the concept of “self-doer”, which represents people’s preference to define themselves as a Verb (executor of the goal) rather than a Noun (owner of the goal). Houser-Marko and Shelton first asked participants to transform their goals into verb phrases for the doers (e.g., “Improve my GPA” to “being an excellent graduate”, and “work in my social life” to “being a friend maker”). Those participants rated each of their doer phrases and figured out the final score. They had found that the construction of “self-doers” can predict their long-term efforts towards personal goals and mediate the effectiveness of self-concordant efforts on sustained efforts. To spread it in another way, self-concordance individuals tend to define themselves as “doers” to a greater extent, which makes them better realize their goals.

Similarly, Smith et al. [30] had also conducted a research on 97 British athletes throughout the season. It was released that autonomous goal motivation at the beginning of the season prompted efforts during the season. Accordingly, the goal achievement and emotional happiness at the end of the season can be hereby predicted.

3.1.4 The Impacts on Cognition

Moberly et al. [31] pointed out that autobiographical knowledge acquisition is accessible during goal-pursuing where participants can better understand autobiographical information and self-concordance goals. While the acquisition of general event knowledge is relevant to a self-concordant goal rather than a self-unconcordance goal. Crane et al. [32] reported similar findings.

Intention for implementation refers to a form of plan in which a person decides to take concrete action at a certain time point in the future or on a specific clue. As we know, it is good to make a plan, however, the action can never happen unless he or she truly wants to realize the goals at a certain moment when the plan transforms into a relevant future [33]. Koestner et al. [34] discovered that those with self-concordant goals may spontaneously adopt implementation intention. Similarly, Carraro et al. [35] found that the motivation of self-concordance promotes the spontaneous generation of implementation intention, which partly mediates the effect of self-concordance on goal acquisition.

Downes et al. [36] had conducted a related studied for 2 times, which indicates that goal motives implicate goal-specific outcomes, and individuals’ overall composition of goal motives—across their goals—shapes their goal efficacy and PO fit perceptions. These mechanisms relate to distal outcomes of goal accomplishment and job satisfaction.

Zhang et al. [37] discovered that perceived performance and self-concordance are two sources of information people may utilize to judge meaning in goal directed behaviors, and that either variable can adequately support the presence of meaning, even in the absence of the other.

Dickerhoof [38] found that those activities promoting happiness by expressing gratitude and optimism can be more effective when combined with self-concordant motivation.

Aidan. Smyth et al. [13] studied the relations among trait mindfulness, self-concordance, and goal progress and they discovered that mindfulness positively associates with setting self-concordant goals (Studies 1–3), which predicts greater goal progress in turn (Studies 2 and 3).

Sheldon et al. [39] measured the two-cycle “upward spiral” model concerning freshmen’s adaptability by adopting short-term individual design and PLOC evaluation. They hypothesized that those freshmen with better goal self-concordance tend to be more adaptable at the beginning of admission for the reason that they can maintain the self-processing of “self-development” and “continuous progress”. By introducing path modeling procedures, the results have shown that freshmen with high self-concordance can achieve their goals better in the first semester, which in turn improves their adaptability in the first semester. Furthermore, the achievement in the first semester leads to higher goal self-concordance in the second semester, which sets more goals in the second semester, and leads to better adaptability again (these improvements are compared with the first semester). Moreover, the achievement of annual goals indicates the improvement of self-development for those freshmen during the university period. These results demonstrate that people improve happiness and adaptability through the continuous pursuit of self-appropriate goals.

Milyavskaya et al. [40] found that actual behaviors play a mediating role between goal self-concordance and psychological need satisfaction, that is, goal self-concordance can promote individuals to take real actions.

Gaudreau [24] had studied 220 undergraduates and found that students with a high level of goal self-concordance tend to acquire higher learning satisfaction and learning performance.

Werner et al. [41] studied 176 college students and discovered that the pursuit of goal with high self-concordance can be easier achieved, which attributes to the thought of subjectively believing that self-concordant goals can be easier, rather than the efforts to achieve these goals. This study provides us with a novel perspective.

Zhang et al. [15] researched 172 employees and 25 supervisors in the management field, which released that the relationship between the supervisor feedback environment and creative performance is mediated by goal self-concordance perfectly and moderated by creative personality significantly. It is hereby revealed that goal self-concordance also has a positive predictive effect on producing performance.

Viewing from the above-mentioned literature review, it is noted that the researches on the goal self-concordance mainly focuses on the impacts of it on the individual, including the impact on all aspects of psychology and behavior results. The current research has not covered a wider scope yet.

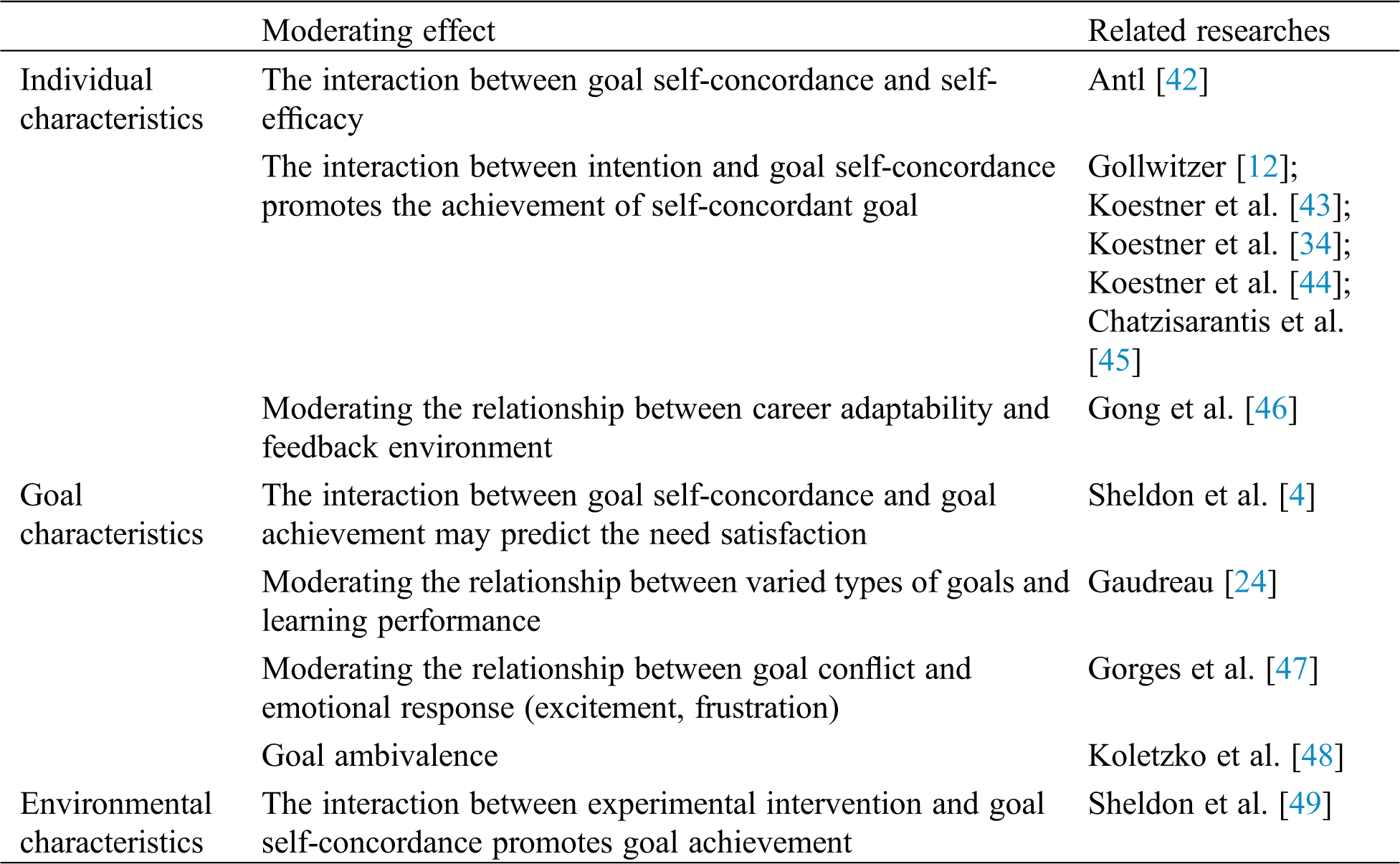

3.2 The Moderating Effect of Goal Self-Concordance

The impacts of goal self-concordance on the results are not independent, many studies have released the single effect, moderating effect, and mediating effect of goal self-concordance. The mediating effect is later discussed in the part of influence outcome and antecedents of goal self-concordance. The moderating effect is hereby described in Tab. 2. There are not that many existing researches, which can be divided into three categories: individual characteristics, goal characteristics, and environmental characteristics.

Table 2: Related research on the effect of goal self-concordance

3.2.1 Individual Characteristics

Antl’s [42] study on 135 college students verified the combined action of goal self-concordance and self-efficacy, which indicates that the increase of self-efficacy emphasizes the relationship between self-concordance and outcome variables. The goal achievement and wellbeing of the individual with high self-efficacy are higher than that of the individual with lower self-efficacy. Moreover, the combined moderating effect of goal self-concordance and self-efficacy is better than that of either factor alone.

Many pieces of literature have illustrated that intention for implementation has a positive impact on goal achievement [12]. However, some other studies have also pointed that these effects may occur, or seems most manifest only when the underlying goal is self-concordant. Koestner et al. [43] found the interaction between goal self-concordance and intention for realization in two longitudinal studies, while the intention is helpful to the realization of self-concordance goal, rather than self-unconcordance goal. Koestner et al. [44] replicated this basic finding in 2008. Chatzisarantis et al. [45] demonstrated the effect of personal goals on health behavior in a randomly assigned experimental study, which indicates the combined effect of motivation for self-concordant goal and intention for implementation produced a state that met the highest level of multivitamin intake program within 2 weeks.

The purpose of Gong’s [46] study is to investigate the role of career adaptability, feedback environment, and goal-self concordance in improving police psychological safety. It is shown that career adaptability indirectly influences psychological safety through the feedback environment. Career adaptability has a greater influence on improving psychological safety for police officers with lower goal-self concordance than for individuals with higher goal-self concordance. Police officers with lower goal-self concordance must care about their future work roles, control their professional activities, make education and career choices based on curiosity, and be confident in their careers to improving their psychological safety.

Sheldon et al. [4] discovered that a higher score of goal self-concordance may lead to more dominantly autonomous motivation. In the process of goal pursuit, positive emotions and satisfaction is positively correlated with the efforts to be made and the possibility of achieving goals. Meanwhile, the achievement of these goals is closely relevant to the strong need-based experience involving autonomy, competence and relationship in daily life. And the increasing experience of need satisfaction over time tends to produce higher overall well-being. Therefore, the interaction between goal self-concordance and goal achievement can predict the need for satisfaction when goal and self are highly integrated.

Gaudreau [24] found that the goal of mastering certain methods is positively correlated with learning satisfaction and performance, which is merely detected in those students with a higher level of goal self-concordance, and goal of the performance is also related to high performance in this case. However, for students with lower level of goal self-concordance, both of the above-mentioned goals are associated with anxiety. The author of this paper suggests that scholars may consider the joint effect of content and motivation of goal on educational outcomes.

Gorges et al. [47] studied the self-concordance degree of conflict goals perceived by 647 young scientists, which strives to reveal the role of goal self-concordance degree in goal conflict and emotional response. It is found that goal self-concordance explains the differences between goal significance and accessible emotional response. The subjects tend to show positive emotional responses (such as excitement) to two conflicting goals with high level of goal self-concordance. While those with lower level of goal self-concordance are inclined to have negative emotional reactions (such as frustration) when they are faced with the same situation.

Koletzko et al. [48] introduced the concept of low goal ambivalence as the related-linked factor of goal self-concordance. In the three studies, the hypothesis, that freshmen’s ambivalence toward the completion of graduating goals regulates the impacts of goal self-concordance on subjective well-being, is comprehensively studied. In study 1 and study 2, the difference of goal ambivalence explained the effect of goal self-concordance on life satisfaction and emotion at the end of freshman year. Moreover, study 3 demonstrates that goal ambivalence has a longitudinal mediating effect on the promotion of freshmen’s life and learning satisfaction one year after enrollment. Such kind of mediating effect is reflected in and explained by the perception of Freshmen’s progress toward their final goal. The decomposition of self-concordance into autonomous motivation and controlled motivation may result in a non-redundant parallel effect respectively on the two sub-components. These results indicate that ambivalence acts as an important experience of goal pursuit, which represents an additional explanatory variable in the SCM of goal pursuit and longitudinal happiness.

3.2.3 Environmental Characteristics

Sheldon et al. [49] conducted a longitudinal experimental study in which half of the participants are guided concerning their target tracking strategies after determining the goals for this semester. They found an interaction that is similar to the intention of implementation [45,43]. The experimental intervention restricts the realization of goals in those participants whose goals were initially self-concordant.

It can be seen that goal self-concordance may regulate this process together with other factors when the goal is achieved or other behavioral results are achieved. Existing studies focus on the joint effects of individual characteristics, content and category of goal, motivation goal, and some environmental characteristics, such as the joint effect of the experimental intervention and goal self-concordance. Necessary as it should be, it is recommended to explore the joint effects of goal self-concordance and other factors from a broader scope or perspective, which helps to provide a broader vision.

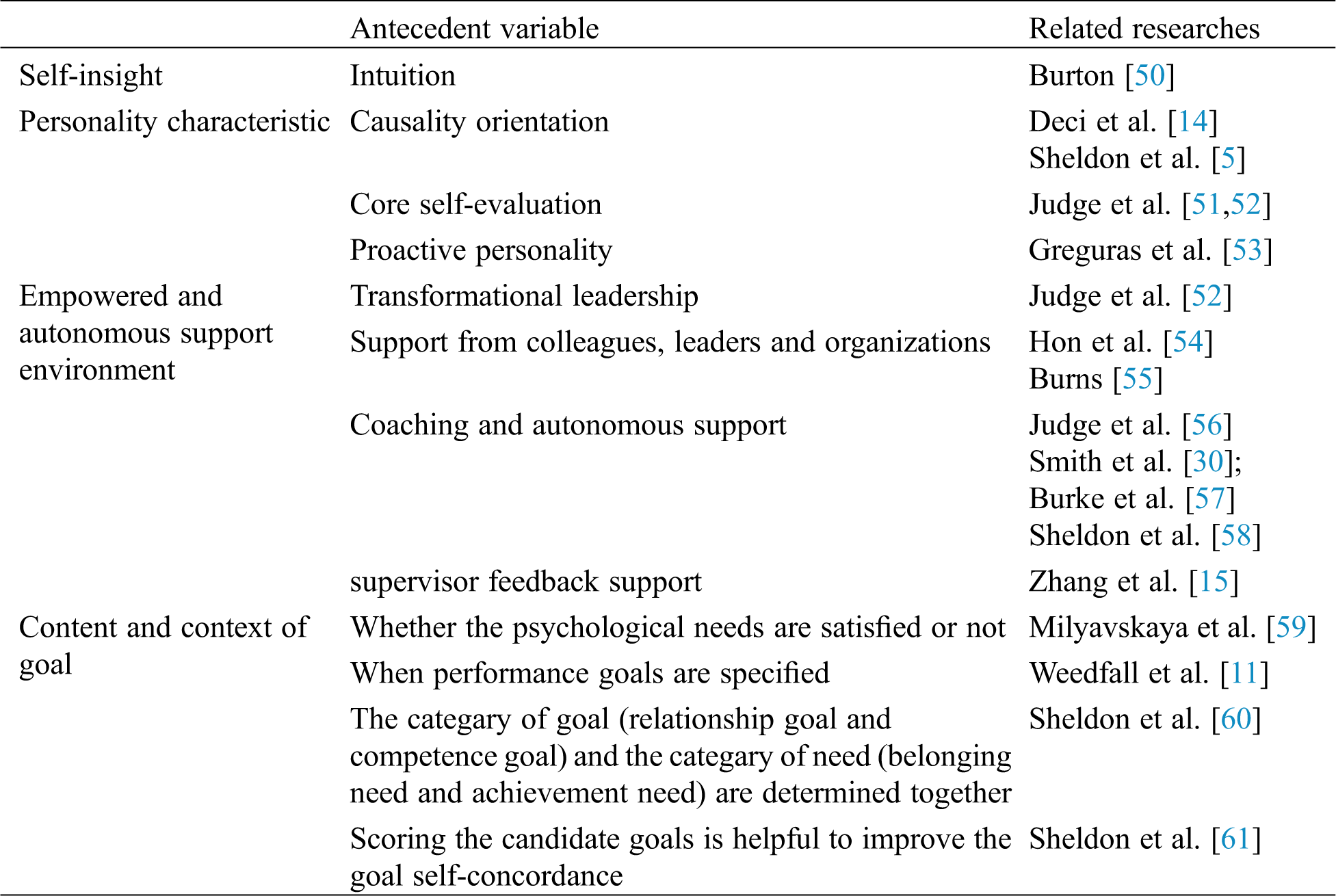

3.3 Antecedents of Goal Self-Concordance

Motivation is considered stable for those with self-concordant goals, and their question generally turns out as “how can I maximize the performance of my goal?” While the question for those who are unconcordance is unstable, that is, “how can I ask others to improve my motivation?” Therefore, it is particularly important to explore the antecedents of goal self-concordance. The research on the antecedents of goal self-concordance, that is, what kind of factors concerning oneself or environmental conditions affect people’s goal self-concordance, is relatively less when compared with the outcome variable of goal self-concordance. Those antecedents are hereby roughly summarized into following four aspects, as illustrated in Tab. 3, including self-insight, personality characteristic, authorized and autonomous support environment, as well as content and context of goal.

Table 3: Related researches on antecedents of goal self-concordance

Burton [50] had verified the self-insight of an individual through two studies, that is, one’s understanding of his or her inner self, has great impacts on the choice of self-concordant goals. The study also demonstrates that goals set according to intuition are generally self-concordant. In the first study, the subjects adopted the goal selection attribution method to evaluate the concordance between their goals and self, and answered the question of “does the goal originates from your intuition or rational thinking?” And the results indicate that intuition-based goals tend to show a higher level of goal self-concordance. In the second study, subjects were randomly assigned to a “rational group” or a “intuitive group” to set goals under the guidance of varied guidelines. The results reveal that the goal self-concordance of the intuitive group is significantly higher than that of rational group. Therefore, complying with intuition may improve the self-concordance of goals.

3.3.2 Personality Characteristic

Literature also indicates that individuals with certain personality characteristics are more likely to find self-concordant goals. Judge et al. [51] conducted a study on the impact of one’s core self-evaluation on goal self-concordance, which indicates that core self-evaluation has a significant positive impact on goal self-concordance. They hold the opinion that individuals who treat themselves positively are more inclined to resist pressure, and they are more likely to affirm themselves. They also tend to form goals consistent with themselves when setting goals since they care more about their internal demands than external requirements. Additionally, goal self-concordance plays a mediating role in the relationship between core self-evaluation and job or life satisfaction [51,52].

According to the causality orientation theory, which is developed from self-determination theory, Deci et al. [14] discovered that people may adopt causal orientation to attribution. Causal orientation refers to the personality or characteristic, which is the tendency of individuals to stably perceive the degree of self-determination of external activities. Sheldon et al. [5] found that personal causal orientation also has an impact on goal self-concordance. Autonomy orientation is positively correlated with goal self-concordance, while control orientation has a major negative correlation with goal self-concordance.

Besides, Greguras et al. [53] discovered that individuals with proactive personalities tend to set self-concordant goals.

3.3.3 Empowered and Autonomous Support Environment

A study on employees’ creativity in China [54] measured several external factors: leadership empowerment, support and assistance from colleagues, and organizational modernization. The three factors respectively have an independent impact on the motivation of self-concordant work, and further predict the employees’ creativity of supervisor evaluation. These findings demonstrate the impact of three situational variables (empowerment at the level of colleague, supervisor, and organization) on self-concordance. It is hereby released that empowering leadership has a significant impact on goal self-concordance. Transformational leaders [55] enable employees to choose goals with higher self-concordance. “Transformational leader” refers to those who have the power to improve followers’ enthusiasm and morale by connecting their identity with the project and passing information to them, hereby empower and motivate followers to identify what they want in the organization. Judge et al. [56] discovered that transformational leadership has a major positive impact on goal self-concordance, while the latter plays a mediating role between transformational leadership and employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Zhang et al. [15] had also pointed out that supervisor feedback support has positive effects on employees’ goal self-concordance and promotes the performance of them.

In another study concerning organizational behavior, Burke et al. [57] randomly selected one of the three goals set by the subjects, namely senior managers, to conduct one-to-one coaching, and the other two goals are set as the control group without any coaching. The results indicate that the goal self-concordance of all goals has been well improved, and the concordance of the group receiving coaching is significantly higher than that of the other two groups. The results show that coaching or training may increase the goal self-concordance of senior managers. Acting as one of the few controlled trials to prove the effectiveness of life guidance, this case indicates that training or coaching enables participants to make more suitable choices concerning their self-concordant goals.

Smith et al. [30] also verified the goal SCM in the related field of sports, which indicates that perceived coaching autonomy support can predict an athlete’s choice of self-concordant goal. By supporting choice and proxy, the coaches can empower athletes to choose self-concordant goals. The study also discovered that coaches’ self-support positively affected autonomous motivation and needs satisfaction. A study of Sheldon et al. [58] found a similar effect, showing that student-athlete tends to present strong self-concordant motivation when participating in physical education, club sports, and university sports and receiving autonomy support from their coaches. The research also illustrates that the effect can be more significant for the group composed of university athletes considering their high level of pressure, and it may be particularly important for professional athletes to be guided by a supportive coach that they can maintain their original competitive motivation.

3.3.4 Content and Context of Goal

In addition to the internal psychological process and cognition, the choosing of goal self-concordance is also related to the context of the goal. In the research of Milyavskaya [59], the subjects were required to set goals in two varied situations and went through investigation upon whether the situation can meet the psychological needs of the subjects and the degree of goal self-concordance. The results have shown that the degree of goal self-concordance can be higher where the psychological needs are met.

Weedfall [11] assigned a performance goal for his undergraduates to evaluate the goal self-concordance and determine whether the self-concordance of the assigned goal is related to the self-concordance of the self-setting goal. Whose results illustrate that the assigned goal cannot affect the self-concordance, nor can it affect the goal acquisition and sense of well-being.

Sheldon et al. [60] conducted a further study on the influencing factors of goal self-concordance level concerning 103 students in the social psychology class of the University of Missouri. The results reveal that the level of goal self-concordance is determined by people’s motivational orientations (belonging needs and achievement needs) and the category of goals (relational goals and competence goals). The subjects tend to show more interest and engagement, as well as less pressure and a sense of being forced when the range of assigned goals matches their needs and motivation.

Sheldon et al. [61] continued to study how people “Cross the Rubicon”, that it, making up their mind when choosing personal goals. In study 1 and study 2, participants scored the goal self-concordance of the four candidate goals before choosing the two they desperate to pursue. There is a high degree of matching among the intrinsic goal, the content of the goal, and participants’ values and motivation. Self-concordance explains participants’ actual choice of goals. In longitudinal study 2, the choice of internal goal predicted the increase of well-being. In experimental study 3, participants who scored the candidate made more intrinsic choices on average. It is hereby concluded that one’s motivation for various candidate goals is conducive to improve the goal selection.

There are relatively fewer studies on its antecedents when compared with the research on the effect of goal self-concordance. However, the findings of individual or environmental variables that can affect goal self-concordance help to improve the level of goal self-concordance, which further reduces or avoids the occurrence of goal self-unconcordance. Improvement of individual psychology at all levels can ultimately promote personality and behavior achievements.

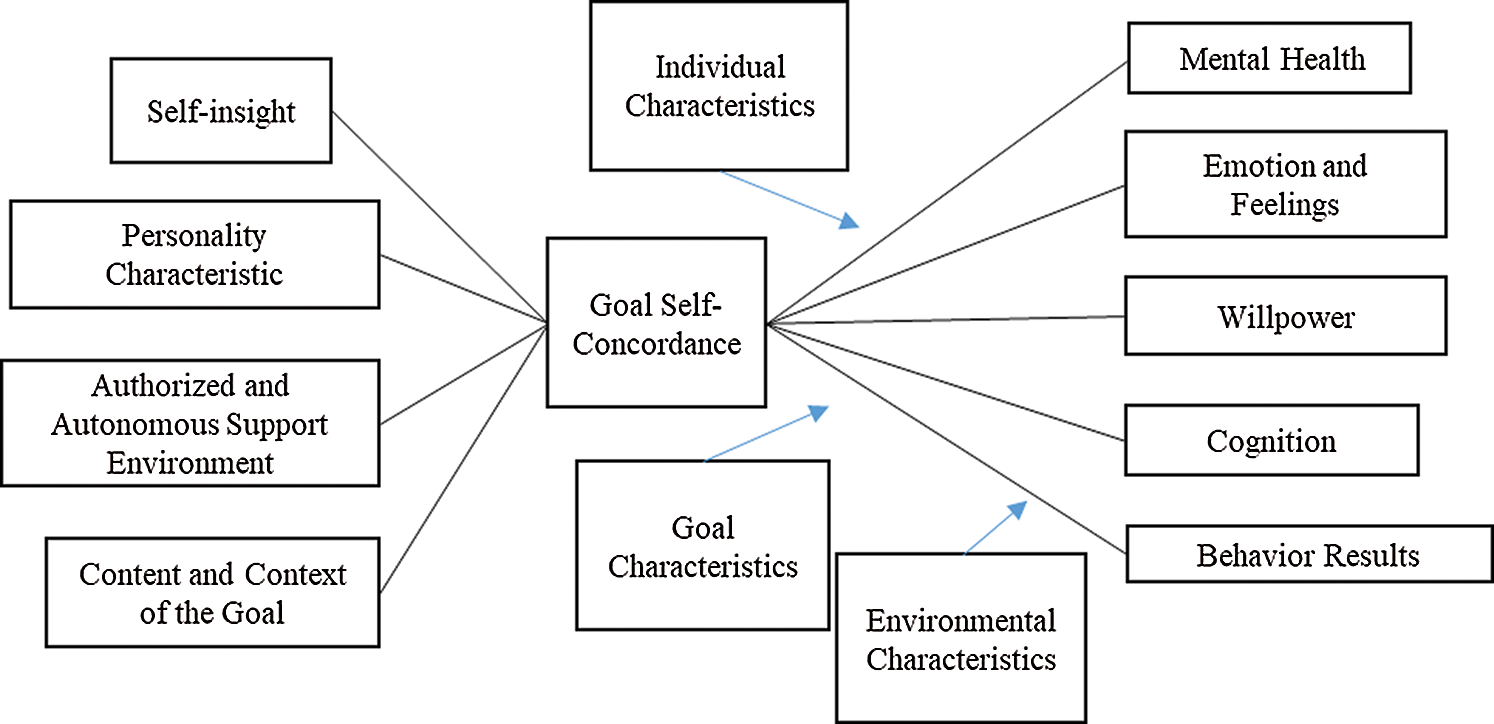

The goal self-concordance model explains the integrated degree of goal and self from the essential perspective of “authenticity” and “true self”, which acts as a major advancement in the development of positive psychology. Although the goal SCM is developed based on the self-determination theory, its self-concordant logic is featured with the evidence for its theoretical difference to SDT, which is essentially different from the goal-setting theory. It can be seen from the above-mentioned pieces of literature on goal self-concordance that there are subtle differences in the measurement of goal self-concordance, and there are also disputes concerning whether to measure “quality” or “quantity”. Such kind differences and controversies are originated from varied research objects and purposes, while these benign disputes can promote the improvement and perfection of the measurement method of goal self-concordance. Existing studies have extensively conducted empirical and theoretical studies on the antecedents, involvement, and impacts of goal self-concordance in varied research objects and fields (See Diag. 1). In terms of the impacts of goal self-concordance, it reveals that goal self-concordance has a widespread and far-reaching influence on individual positive psychology, emotion, and behavior. The impacts are hereby summarized into four aspects: mental health, emotion, and feeling, willpower, cognition, and behavior outcomes. Although some literature has revealed the single effect of goal self-concordance, it is well known that such effect does not exist alone, instead, it affects these outcome variables separately or together with individual characteristics, goal characteristics, and environmental characteristics. The effects are also affected by self-insight, personality characteristics, empowered and autonomy support environment, as well as content and context of the goal itself. These research results significantly contribute to promoting positive psychology and other disciplines.

Diagram 1: Related researches on goal self-concordance

The goal SCM indicates that people’s choice of goals expressing fundamental interests, values, talents, demands, and motivations is more conducive to their mental health, happiness, and self-fulfillment. Contrarily, people tend to waste a lot of time and energy to approach the uncertain future when they choose the “wrong” goal. In this case, the unconcordance between goal and self may turn into a major obstacle to the development of one’s personality development. Goal self-concordance provides a vital perspective for lifelong personality development, assuming that people have a natural tendency of growth and maturity, namely assimilation and adaptation, difference and integration. To achieve better integrated and more energetic status in a larger group, it is recommended that may stimulate and guide human beings to establish more ultimate and noble pursuit concerning life and work from a more essential perspective. The existing studies not merely illustrate the extensive application of goal SCM but highlight the necessity and significance of more in-depth and extended researches. Based on the existing literature, the followed-up exploration is suggested to be implemented from the following aspects to provide novel research perspectives and dated academic achievements.

4.1 The Expanded Research on Individual

Existing studies have demonstrated that parts of personality characteristics can predict goal self-concordance, then which personality characteristic or individual traits may have a positive impact on goal self-concordance? Now that one’s goal self-concordance reflects his or her motivation in PLOC, then whether if positive individual characteristics affect the level of individual motivation and further lay impacts on goal self-concordance? For instance, the promotion focus and prevention focus in regulatory focus theory [62] are inclined to oppose each other, the differences lie in the aspects of behavioral motivation, goal outcome, strategic approach, reaction to the outcome and emotional experience, etc. It’s worth studying that whether varied regulation tendencies may have different effects on goal self-concordance. Certainly, some other individual characteristics may also affect the self-concordance of goals, which requires further exploration.

Conversely, goal self-concordance affects one’s positive psychology in a wide and far-reaching way. Existing researches on the outcome variables of goal self-concordance focus on positive psychological outcomes and cognition, such as need satisfaction, mental health, sense of wellbeing, adaptability, psychological empowerment, and organizational commitment, etc. While researches on behavior are reflected in one’s continuous pursuit and effort for self-concordant goal. In addition to that, whether if high level and organization-based goal self-concordance may have effects on the other positive initiatives such as work commitment, voice, organizational citizenship-based behavior, and innovation behavior, etc. Furthermore, whether if goal self-concordance may affect the individual initiative in the related fields of education, health care, sports, politics, etc. Related researches on this topic will greatly enrich the application and research of positive psychology in various fields, which is featured with positive theoretical and practical significance.

4.2 Expanded Research on Environment

It can be seen from the Existing literature that suggests that goal self-concordance is affected by both individual characteristics and environment. Downes et al. [37] revealed that the motivation for goal self-concordance can affect the perceived PO fit (Personal-Organization fit), then it can be hereby deduced that whether if the improvement of matching degree between the individual and the organizational environment may promote the goal self-concordance of an individual? Which remains a meaningful study to be conducted.

Existing studies have found that coaching and intervention, organizational support, and supervisor feedback support are conductive to promote goal self-concordance, where transformational leadership has a significant positive impact on goal self-concordance, and the latter plays a mediating role between transformational leadership and employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Then, whether if the other leadership styles may affect the goal self-concordance and the choice of self-concordant goal equally or more effectively? For example, the spiritual leader, which developed from the intrinsic motivation model, focuses on the spiritual demands and intrinsic value demand of employees. It actively guides employees’ positive psychology, stimulates their intrinsic motivation, which concurrently lay positive impacts on employees’ transcendental self-concept and autonomous psychology [63]. Then will it also have positive impacts on goal self-concordance? Whether if there are any other leadership styles, such as service leadership or service coaching, more effective in promoting goal self-concordance? Even more, the impacts of varied leadership or coaching styles on goal self-concordance can also be compared and analyzed. Researches on these topics will contribute to enrich the supervisor theory and guide the practice of the supervisor. If there are any other environmental factors, such as different social norms and social expectations, that may have strong impacts on the goal self-concordance?.

4.3 Further Discussion on Research Methods and Perspectives

Goal self-concordance provides a vibrant perspective for the development of lifelong personality, scholars tended to carry out cross-sectional study or short-term follow-up studies. The long-term follow-up study is hereby recommended to explore the role of goal self-concordance in promoting personality development. Considering that goal self-concordance itself may change with the change of outer environment, long-term follow-up research is more conducive to uncover the hidden laws that affect the development and change of goal self-concordance.

Most of the existing researches focus on the impact of goal self-concordance on positive psychology and behavior. It is well known that society is composed of varied groups, while the mechanism of the impacts of varied goal self-concordance on group psychology and behavior remains unknown. Therefore, conducting advanced research on those groups is not merely conducive to the realization of a broader theoretical effect, but contributes to the promotion and improvement of practices in positive psychology.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the Editor for his hard work in processing this article. Helpful comments from the anonymous reviewers are greatly appreciated.

Funding Statement: Youth Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71702068).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J., Ryan, R. M. (2004). Self-concordance and subjective well-being in four cultures. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 35(2), 209–223. DOI 10.1177/0022022103262245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Austin, J. T., Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120(3), 338–375. DOI 10.1037/0033-2909.120.3.338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Emmons, R. A. (1989). The personal striving approach to personality. In: Pervin, L. A. (ed.Goal concepts in personality and social psychology, pp. 87–126. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

4. Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 482–497. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sheldon, K. M., Kasser, T. (1995). Coherence and congruence: Two aspects of personality integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(3), 531–543. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J. (1998). Not all personal goals are personal: Comparing autonomous and controlled reasons for goals as predictors of effort and attainment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(5), 546–557. DOI 10.1177/0146167298245010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). Goal achievement: The role of intentions. European Review of Social Psychology, 4(1), 141–185. DOI 10.1080/14792779343000059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bandura, A., Wood, R. (1989). Effect of perceived controllability and performance standards on self-regulation of complex decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(5), 805–814. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. de Charms, R. C. (1968). Personal causation: The internal effective determinants of behavior. USA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

10. Ryan, R. M., Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749–761. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Weedfall, A. (2016). Need-supportive goal assignment and the self-concordance model: A moderated serial mediation (Ph.D. Thesis). North Carolina State University, USA. [Google Scholar]

12. Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(7), 493–503. DOI 10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Smyth, A. P. J., Werner, K. M., Milyavskaya, M. (2020). Do mindful people set better goals? Investigating the relation between trait mindfulness, self-concordance, and goal progress. Journal of Research in Personality, 88(1), 104015. DOI 10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. DOI 10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang, J., Gong, Z., Zhang, S. (2017). Effects of the supervisor feedback environment on creative performance: A moderated mediation model. Academy of Management Proceedings, vol. 2015, no. 1, pp. 13460. Briarcliff Manor, NY. [Google Scholar]

16. Sheldon, K. M. (2014). Becoming oneself: The central role of self-concordant goal selection. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(4), 349–365. DOI 10.1177/1088868314538549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Oxford, UK: University Rochester Press. [Google Scholar]

18. Sheldon, K. M., Kasser, T. (2001). Goals, congruence, and positive well-being: New empirical support for humanistic theories. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 41(1), 30–50. DOI 10.1177/0022167801411004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Locke, E. A., Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. DOI 10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ryan, T. A. (1970). Intentional behavior. USA: Ronald Press. [Google Scholar]

21. Hirt, E. R., Melton, R. J., McDonald, H. E. (1996). Processing goals, task interest, and the mood-performance relationship: A mediational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 245–261. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang, M., Che, H. (1999). Goal setting theory and its latest progress. Progress in psychological science, pp. 35–40 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

23. Sheldon, K. M., Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(2), 73–82. DOI 10.1080/17439760500510676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Gaudreau, P. (2012). Goal self-concordance moderates the relationship between achievement goals and indicators of academic adjustment. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(6), 827–832. DOI 10.1016/j.lindif.2012.06.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang, T. (2009). The relationship between goal self-concordance and organizational commitment: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Market Modernization, 10, 111–112 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

26. Ernst, A., Philippe, F. L., D’Argembeau, A. (2018). Wanting or having to: The role of goal self-concordance in episodic future thinking. Consciousness and Cognition, 66(1), 26–39. DOI 10.1016/j.concog.2018.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bailis, D. S., Segall, A. (2004). Self-determination and social comparison in a health-promotion setting. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 26(1), 25–33. DOI 10.1207/s15324834basp2601_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Bailis, D. S., Ashley, F. J., Segall, A. (2005). Self-determination and functional persuasion to encourage physical activity. Psychology and Health, 20(6), 691–708. DOI 10.1080/14768320500051359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Houser-Marko, L., Sheldon, K. M. (2006). Motivating behavioral persistence: The self-as-doer construct. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(8), 1037–1049. DOI 10.1177/0146167206287974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Smith, A. L., Ntoumanis, N., Duda, J. L. (2011). Goal striving, coping, and well-being: A prospective investigation of the self-concordance model in sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33(1), 124–145. DOI 10.1123/jsep.33.1.124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Moberly, N. J., MacLeod, A. K. (2006). Goal pursuit, goal self-concordance, and the accessibility of autobiographical knowledge. Memory, 14(7), 901–915. DOI 10.1080/09658210600859517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Crane, L., Pring, L., Jukes, K. (2012). Patterns of autobiographical memory in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(10), 2100–2112. DOI 10.1007/s10803-012-1459-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sheeran, P., Webb, T. L., Gollwitzer, P. M. (2005). The interplay between goal intentions and implementation intentions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(1), 87–98. DOI 10.1177/0146167204271308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Koestner, R., Horberg, E., Gaudreau, P. (2006). Bolstering implementation plans for the long haul: The benefits of simultaneously boosting self-concordance or self-efficacy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(11), 1547–1558. DOI 10.1177/0146167206291782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Carraro, N., Gaudreau, P. (2011). Implementation planning as a pathway between goal motivation and goal progress for academic and physical activity goals. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(8), 1835–1856. DOI 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00795.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Downes, P. E., Kristof-Brown, A. L., Judge, T. A. (2017). Motivational mechanisms of self-concordance theory: Goal-specific efficacy and person-organization fit. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(2), 197–215. DOI 10.1007/s10869-016-9444-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang, H., Chen, K., Schlegel, R. (2018). How do people judge meaning in goal-directed behaviors: The interplay between self-concordance and performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(11), 1582–1600. DOI 10.1177/0146167218771330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Dickerhoof, R. M. (2007). Expressing optimism and gratitude: A longitudinal investigation of cognitive strategies to increase well-being (Ph.D. Thesis). University of California, USA. [Google Scholar]

39. Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J. (2000). Personal goals in social roles: Divergences and convergences across roles and levels of analysis. Journal of Personality, 68(1), 51–84. DOI 10.1111/1467-6494.00091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Milyavskaya, M., Nadolny, D., Koestner, R. (2015). Why do people set more self-concordant goals in need satisfying domains? Testing authenticity as a mediator. Personality and Individual Differences, 77(1), 131–136. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Werner, K. M., Milyavskaya, M., Foxen-Craft, E. (2016). Some goals just feel easier: Self-concordance leads to goal progress through subjective ease, not effort. Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 237–242. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Antl, S. M. (2011). Is two always better than one? A moderation analysis of self-concordance and self-efficacy on well-being and goal progress (Ph.D. Thesis). University of Ottawa, Canada. [Google Scholar]

43. Koestner, R., Lekes, N., Powers, T. A. (2002). Attaining personal goals: Self-concordance plus implementation intentions equals success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), 231–244. DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Koestner, R., Otis, N., Powers, T. A. (2008). Autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, and goal progress. Journal of Personality, 76(5), 1201–1230. DOI 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00519.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., Hagger, M. S., Wang, J. C. K. (2010). Evaluating the effects of implementation intention and self-concordance on behaviour. British Journal of Psychology, 101(4), 705–718. DOI 10.1348/000712609X481796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Gong, Z., Yang, J., Gilal, F. G. (2020). Repairing police psychological safety: The role of career adaptability, feedback environment, and goal-self concordance based on the conservation of resources theory. SAGE Open, 10(2), 2158244020919510. DOI 10.1177/2158244020919510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Gorges, J., Esdar, W., Wild, E. (2014). Linking goal self-concordance and affective reactions to goal conflict. Motivation and Emotion, 38(4), 475–484. DOI 10.1007/s11031-014-9392-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Koletzko, S. H., Herrmann, M., Brandstätter, V. (2015). Unconflicted goal striving: Goal ambivalence as a mediator between goal self-concordance and well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(1), 140–156. DOI 10.1177/0146167214559711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Sheldon, K. M., Kasser, T., Smith, K. (2002). Personal goals and psychological growth: Testing an intervention to enhance goal attainment and personality integration. Journal of Personality, 70(1), 5–31. DOI 10.1111/1467-6494.00176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Burton, C. M. (2008). Gut feelings and goal pursuit: A path to self-concordance (Ph.D. Thesis). University of Missouri—Columbia, USA. [Google Scholar]

51. Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Erez, A. (2005). Core self-evaluations and job and life satisfaction: The role of self-concordance and goal attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 257–268. DOI 10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Bono, J. E., Judge, T. A. (2003). Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 554–571. [Google Scholar]

53. Greguras, G. J., Diefendorff, J. M. (2009). Different fits satisfy different needs: Linking person-environment fit to employee commitment and performance using self-determination theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 465–477. DOI 10.1037/a0014068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Hon, A. H., Chan, W. W. (2013). Team creative performance: The roles of empowering leadership, creative-related motivation, and task interdependence. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(2), 199–210. DOI 10.1177/1938965512455859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. USA: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

56. Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E. (2003). The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 303–331. DOI 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00152.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Burke, D., Linley, P. A. (2007). Enhancing goal self-concordance through coaching. International Coaching Psychology Review, 2, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

58. Sheldon, K. M., Watson, A. (2011). Coach’s autonomy support is especially important for varsity compared to club and recreational athletes. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 6(1), 109–123. DOI 10.1260/1747-9541.6.1.109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Milyavskaya, M., Nadolny, D., Koestner, R. (2014). Where do self-concordant goals come from? The role of domain-specific psychological need satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(6), 700–711. DOI 10.1177/0146167214524445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Sheldon, K. M., Prentice, M., Halusic, M. (2015). Matches between assigned goal-types and both implicit and explicit motive dispositions predict goal self-concordance. Motivation and Emotion, 39(3), 335–343. DOI 10.1007/s11031-014-9468-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Sheldon, K. M., Prentice, M., Osin, E. (2019). Rightly crossing the Rubicon: Evaluating goal self-concordance prior to selection helps people choose more intrinsic goals. Journal of Research in Personality, 79(3), 119–129. DOI 10.1016/j.jrp.2019.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280–1300. DOI 10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Zhang, J. C., Ling, W. Q. (2011). Review of foreign spiritual leadership research. Foreign Economics and Management, 33(8), 33–40 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |