Mental Health Promotion

| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.015253

ARTICLE

Unpacking the Associations between Traumatic Events and Depression among Chinese Elderly: Two Dimensions of Aging Attitudes as Mediators and Moderators

Department of Social Welfare and Risk Management, School of Public Affairs, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310058, China

*Corresponding Author: Chaoxin Jiang. Email: colinjcx@163.com

Received: 04 December 2020; Accepted: 02 February 2021

Abstract: Traumatic events have been considered significant risk factors for older adults’ mental health, but the mediating mechanism and moderating effect of aging attitudes that underlie this relationship have yet been completely investigated. The attitudes of the elderly toward aging can be divided into two closely related but conceptually different dimensions, including positive and negative. Positive aging attitudes refer to optimistic feelings and experiences about aging, whereas negative attitudes toward aging are related to detrimental thoughts and sensations experienced about the increasing age. The purpose of this study is to explore the mediating and moderating roles of these two dimensions of aging attitudes between traumatic events and depression of the elderly in China. Data for this research come from the China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS) of 2014. A nationally representative sample consisting of 11,511 Chinese older adults aged 60 and above was obtained through a stratified, multi-stage probability sampling method. The results revealed that the association between traumatic events and depression was mediated and moderated by positive and negative aging attitudes, controlling for gender, age, spouse, educational level, and ethnicity. Significance, implications, and limitations were discussed.

Keywords: Traumatic events; depression; aging attitude; elderly; China

The process of the population aging in China has accelerated since 2000, with the number of Chinese elderly aged 60 and above reaching approximately 240 million in 2016. It is estimated that this population of older adults will double to 480 million in China by 2050 [1]. The elderly’s mental health becomes one of the most significant public health issues in population aging because disorders therein can further result in unsettling consequences, such as decreased overall health status, cognitive decline, impaired functioning, disability, and increased risk of suicide [2,3]. To our knowledge, even though numerous studies have explored the underlying mechanisms and protective factors of trauma exposure on individuals’ psychological status during the past several decades, the dual dimensions of aging attitudes both as mediators and moderators have not been simultaneously investigated, especially among Chinese older adults [4,5]. Under such a context, the aim of this study is to examine the mediating and moderating effects of positive and negative aging attitudes between traumatic events exposure and the elderly’s depressive symptoms.

1.1 Traumatic Events and Depression

Traumatic events refer to the deleterious or endangering life events that cause detrimental effects on individuals’ physical and/or psychiatric well-being [6,7]. Generally, traumatic events contain serious injuries, deaths of spouses, unavoidable accidents, overpowering natural diseases, interpersonal trauma, and other events that are overwhelming [8–10]. Traumatic events are experienced by individuals in the whole life cycle, not only in childhood and adulthood, but also in old age [5,9]. Grounded in Turner’s stress process model, experiencing traumatic events is also associated with the elderly’s psychological disorders [11]. To be specific, a traumatized elderly individual experiences declined life satisfaction and a damaged sense of control over their lives, which causes impairment on their mental status [12,13].

A large scope of studies have revealed the relationships between traumatic events and anxiety [14], psychological distress [15], depressive symptoms [16], post-traumatic stress disorder [17], and suicide ideation [18]. For example, Dulin et al. [4] indicated that a higher level of trauma exposure was related to a higher level of depressive symptoms on the basis of a sample of 1,216 elderly individuals in New Zealand [14]. Another study conducted in Japan demonstrated that losing a spouse or close partner increased the risk of suffering depression in a sample of the aged [9]. In addition, a longitudinal survey among a sample of Taiwanese elderly found that experiencing an earthquake contributed to the depression of older adults [19]. Therefore, it is rational to speculate that being exposed to traumatic events is positively associated with depression based on the research reviewed above.

1.2 Positive and Negative Aging Attitudes as Mediators

According to the stress process model, Turner [11] also suggested that the internal personal factor could play a mediating role between trauma exposure and psychological status [11]. In this study, I propose that the aging attitude can be considered a mediator. The aging attitudes can be defined as an individual’s feeling and evaluation of the process and state of aging as they get older [19]. Throughout the literature, prior studies mostly concentrated on the single dimension of aging attitudes of the elderly [20,21]. However, in recent studies, elderly attitudes towards aging are frequently discussed in two tightly related but conceptually distinct dimensions, including positive and negative [22]. Positive aging attitudes refer to optimistic feelings and experiences about getting older, such as enhanced morality and increased wisdom in later life [19]. On the contrary, negative aging attitudes relate to the detrimental feelings and experiences of physical, psychological, and social impairments that accompany increasing age, such as reduced ability and function [23].

Levy’s stereotype embodiment framework illustrated that possessing different views on aging was correlated to opposite consequences [24]. That is, positive aging attitudes are associated with more beneficial outcomes, while negative aging attitudes will lead to more disadvantageous results [19,23]. Numerous studies indicated that positive attitudes towards aging were related to higher well-being [21] and better life satisfaction [25]. Meanwhile, negative aging attitudes were associated with enhanced loneliness [26] and increased depression [27].

Guided by the psychology of attitude theory, an individual’s attitude was not invariant because it could be affected by social contextual factors [28]. In the context of this research, the elderly’s attitudes towards aging may change dynamically due to the occurrence of traumatic events. To illustrate, trauma-exposed elderly individuals are more likely to feel disappointed and useless, which weakens their positive evaluations of their aging process and promotes negative views related to their aging state [22,27]. For instance, O’Brien et al. [29] demonstrated that suffering from serious diseases could generate older adults’ negative aging attitudes. Moreover, Martin et al. [30] compared 1,140 elderly participants with cancer and without cancer, further illustrating that experiencing cancer could cause aging attitudes to be more pessimistic. Taking the literature mentioned together, this study assumes that experiencing traumatic events will undermine positive aging attitudes and reinforce negative aging attitudes, which further results in depression among the elderly Chinese populace.

1.3 Positive and Negative Aging Attitudes as Moderators

Based on the organism–environment interaction model, individuals with distinct mindsets and mentalities react divergently to similar circumstance [31,32]. Specifically, holding positive self-perception of aging may be regarded as a resource that contributes to protect the elderly from negative outcomes to traumatic exposure, while negative attitudes towards aging may strengthen individuals’ vulnerability that results in more adverse reactions [22,33].

The moderating effect of aging attitudes is still controversial in empirical research. Some studies demonstrated that positive aging attitudes could alleviate the deleterious effect of trauma exposure whereas negative aging attitudes would reinforce this impact. For instance, Bellingtier et al. [22] illustrated that older adults with more negative self-perceptions of getting older were more likely to have intense emotional responses to stress exposure. Additionally, another study also suggested that elderly individuals with more positive aging attitudes would react less to stressors when compared to those who have negative aging attitudes [34]. However, Liu et al. [32] argued that the moderating effect of aging attitudes did not exist between perceived poor health status and life satisfaction in the Chinese context. Due to the mixed findings, the moderating role of aging attitudes between traumatic events and depression needs to be further examined.

Although the direct impact of traumatic events on the elderly’s mental health have been widely discussed, the mediating and moderating effects of the dual dimensions of aging attitudes are still needed to be examined. Moreover, few studies have validated the mediating and moderating roles of aging attitudes. On the basis of the research gaps indicated above, I propose the following research hypotheses:

H1: More traumatic events are associated with a higher level of depression.

H2: Aging attitudes mediate the relationship between traumatic events and depression.

H2.1: More traumatic events are associated with a higher level of negative aging attitudes, which in turn, are associated with a higher level of depression.

H2.2: More traumatic events are associated with a lower level of positive aging attitudes, which in turn, are associated with a higher level of depression.

H3: Aging attitudes moderate the relationship between traumatic events and depression.

H3.1: More positive aging attitudes can buffer the influence of traumatic event on elderly’s depression.

H3.2: More negative aging attitudes can strengthen the influence of traumatic event on elderly’s depression.

Data from this study were obtained from the China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS) in 2014, a large-scale nationwide project conducted by the National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China. To find out the difficulties and challenges encountered by the elderly in the aging process and provide support, CLASS 2014 was designed to collect economic, physical, psychological, and intergenerational relationship data from Chinese elders [33]. Previous studies based on CLASS 2014 mainly focused on loneliness, life satisfaction, coping styles, perceived health status, and social support [27,32,35]. The 2014 Survey adopted a stratified multistage probability sampling method covering 134 counties/districts, and 462 rural/urban committees in 29 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities in mainland China [35]. A total sample of 11,511 older people 60 years of age and older was obtained in CLASS 2014. Males accounted for 48.02% and females accounted for 51.98%. The average age of the sample was 70.31 (S.D. = 8.10). The older adults who were not educated in the sample accounted for 31.44% while those with senior high school education or above accounted for 15.73%. The descriptive statistics of the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants were shown in Tab. 1.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants

Traumatic Events: For the CLASS 2014 survey, participants were asked whether the following events happened in their lives during the last year: serious illness, natural disaster, death of a spouse, death of a child, death of other relatives and friends, loss of property, family seriously ill, conflict with relatives and friends, and/or accident. Each item was coded as “0 = not happened,” or “1 = happened.” I added up the scores for these nine items to assess the traumatic events, with a higher score indicating more traumatic events.

Attitudes Towards Aging: The adapted version of the Attitudes to Ageing Questionnaire (AAQ) was used to measure the attitudes towards aging in the 2014 CLASS [19]. The five-point Likert scale was adopted from, “1 = completely disagree” to “5 = completely agree” to measure positive and negative aging attitudes (psychological growth and psychosocial loss), respectively. The positive aging attitudes subscale included four items, such as, “As people get older they are better able to cope with life.” The negative aging attitudes subscale included three items to measure the psychosocial loss of the elderly. An example of this subscale is, “I see old age mainly as a time of loss.” The present study calculated the mean score of the two subscales respectively, to evaluate the positive and negative aging attitudes, respectively, with higher scores indicating a higher level of aging attitudes in that dimension. The Cronbach’s alpha for the positive aging attitudes and negative aging attitudes subscale were 0.683 and 0.602, respectively. According to the criteria proposed by Nunnally [36], reliability of a scale is acceptable if the Cronbach’s alpha is above 0.60 [36].

Depression: In 2014 CLASS, depression was measured by a revised version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). It consisted of 12 items scored on a Likert scale from 1 to 3. This study calculated the mean value of the 12 items to assess the depression level of older adults. A higher score indicated a higher level of depression in the elderly. This scale showed high reliability in previous Chinese studies [37]. In this study, the Cronbach’s Alpha of this scale was 0.813, indicating high reliability.

Covariates: In this study, the socio-demographic characteristics, including gender (1 = male, 2 = female), age, marital status (1 = married, 2 = single, divorced or bereaved), educational level (from 1 = uneducated to 5 = college or below), and ethnic group (1 = Han, 2 = ethnic minority) were controlled in the analysis.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations were implemented using SPSS 24.0. Both of the mediating and moderating roles of aging attitudes were validated in the PROCESS SAS macro. For analyzing mediators, the direct effect and indirect effect were calculated and the significance of the indirect effect through potential mediators (positive and negative aging attitudes) was determined using a bootstrapping method (5,000 bootstrap samples) with 95% bias-corrected accelerated confidence intervals (CI). The effect is considered statistically significant if there is not a ‘‘zero’’ between the upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI [38]. In terms of moderators, the interaction of traumatic events × positive aging attitude and the interaction of traumatic events × negative aging attitude were calculated and analyzed. The function was graphed for two levels of independent variable and moderator (mean – 1S.D. and mean + 1S.D.) in simple slope analyses [39].

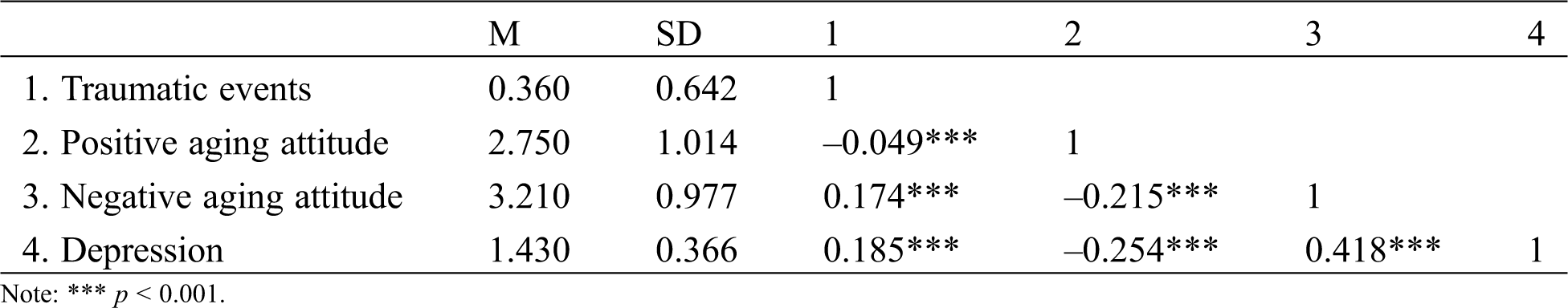

The means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlations of key variables were presented in Tab. 2. As shown, traumatic events, depression, positive aging attitudes, and negative aging attitudes were significantly correlated with one another. Specifically, depression was positively correlated with traumatic events (r = 0.185, p < 0.001) and negative attitudes towards aging (r = 0.418, p < 0.001), and negatively correlated with positive aging attitudes (r = −0.254, p < 0.001). Positive aging attitudes and negative aging attitudes were negatively correlated with one another (r = −0.215, p < 0.001).

Table 2: Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of key variables

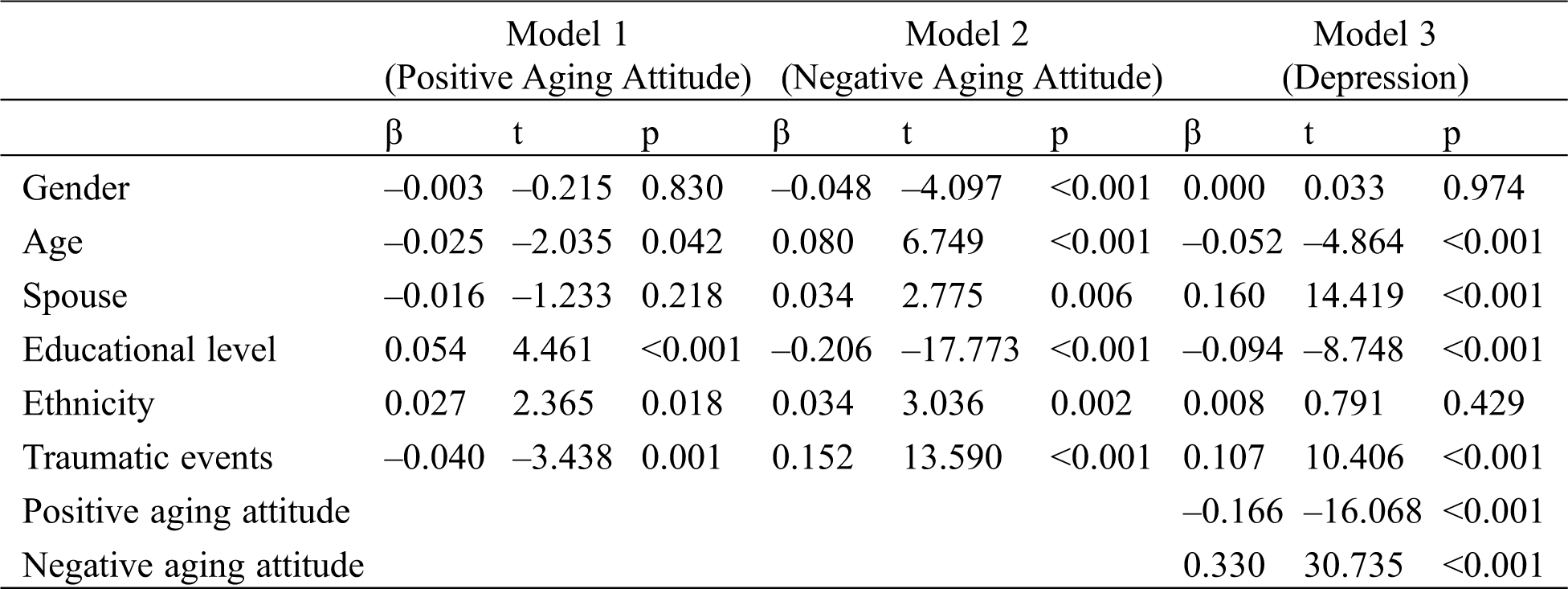

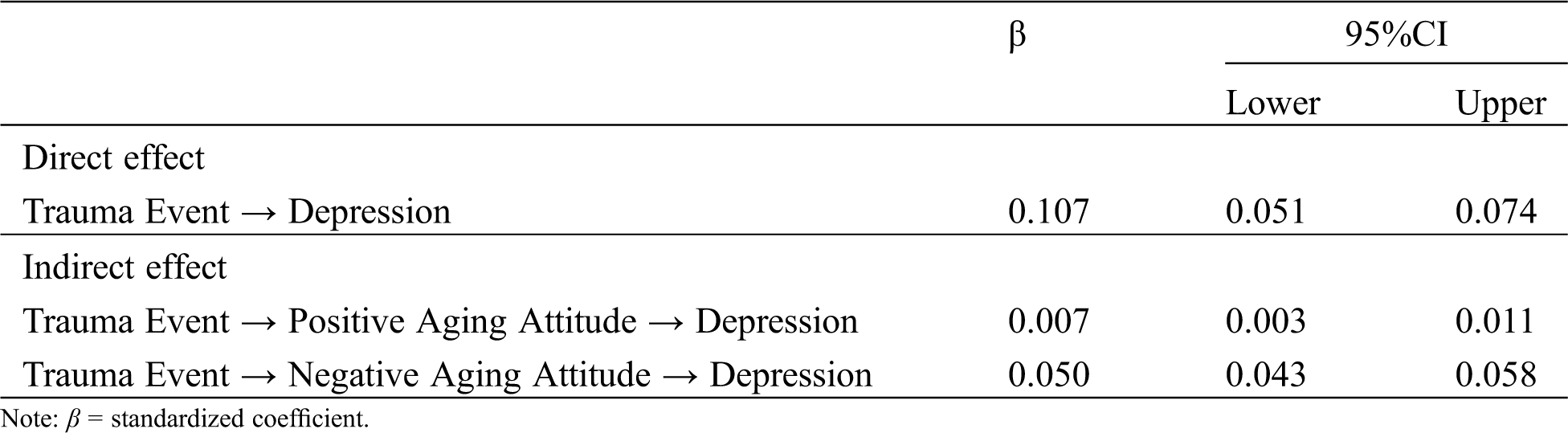

I expected that positive and negative attitudes towards aging would mediate the association between traumatic events and depression of older people. To test this hypothesis, I estimated the parameters for three regression models. The specification of these models was shown in Tab. 3 and the direct and indirect effects were presented in Tab. 4. The results indicated that traumatic events were directly and positively predictive of depression (β = 0.107, p < 0.001). Moreover, traumatic events were positively related to negative aging attitude (β = 0.152, p < 0.001) and negatively related to positive aging attitude (β = −0.040, p < 0.01). Positive aging attitude predicted a low level of depression (β = −0.166, p < 0.001), while negative aging attitude predicted a high level of depression (β = 0.330, p < 0.001). The bootstrap test indicated that the indirect effect of traumatic events on depression via positive aging attitudes (β = 0.011, 95% CI [0.004, 0.017]) and negative aging attitudes (β = 0.080, 95% CI [0.068, 0.093]) were significant. Taken together, traumatic events increased negative attitudes towards aging and reduced positive attitudes towards aging, thereby increasing the level of depression of older people. The overall model accounted for 24.8% of the variance in the elderly’s depression. To clearly present the results, the mediation effects were shown in Fig. 1.

Table 3: Validation of the mediation model

Table 4: Direct and indirect effects with 95% confidence intervals (CI)

Figure 1: The results of mediation model

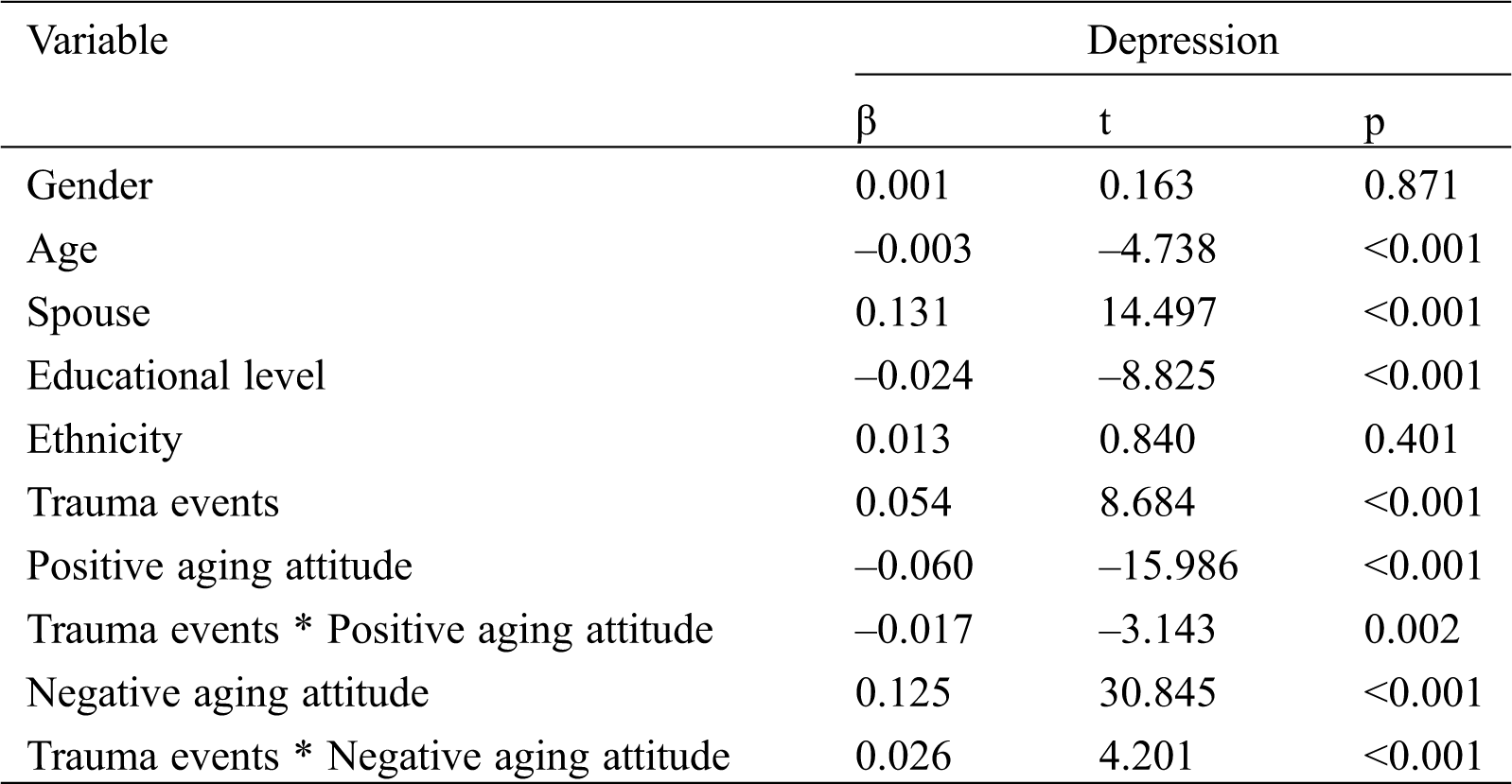

As Tab. 5 illustrated, the interaction effect of trauma events and positive aging attitude on depression (β = –0.017, p < 0.01) and the interaction effect of trauma events and negative aging attitude on depression (β = 0.026, p < 0.001) were both significant in this study. To facilitate the interpretation of this interaction effect, Fig. 2 presented the predicted depression value as a function of trauma events and positive aging attitude; meanwhile Fig. 3 showed the predicted depression value as a function of trauma events and negative aging attitude. Simple slope tests showed that, for older adults with high positive aging attitude, the positive prediction of trauma events on depression (Bsimple = 0.039, p < 0.001) was weaker than for those with low positive aging attitude (Bsimple = 0.072, p < 0.001). On the contrary, for older adults with high negative aging attitude, the positive prediction of trauma events on depression (Bsimple = 0.080, p < 0.001) was stronger than for those with low negative aging attitude (Bsimple = 0.029, p < 0.001). This result indicated that positive aging attitude buffered the detrimental effect of stressful events on the elderly’s mental health, whereas negative aging attitude strengthened this impact.

Table 5: Validation of the moderation model

Figure 2: Positive aging attitude as a moderator of the relationship between Trauma events and depression

Figure 3: Negative aging attitude as a moderator of the relationship between Trauma events and depression

Even though the present study indicates that being exposed to traumatic events contributes to depression, as previous literature has also supported [4,9,16], this study suggests that both positive and negative aging attitudes have mediating and moderating effects in this association. The findings are dissertated as follows.

Consistent with preceding studies, this study supports that more traumatic events decrease positive aging attitudes and exaggerate negative aging attitudes [29,30], which further lead to a higher level of depression [27]. A potential explanation can be that traumatized older adults are more likely to develop a cognitive style of self-criticism for their undeveloped coping style and attribute it to the cause of aging [18], which may enhance the occurrence of depression as a serious form of self-blame. These findings also echo the stress process model, stereotype embodiment framework and the psychology of attitude theory [11,24,28]. That is, traumatic events, such as bereavement or experiencing natural diseases, may make the elderly conscious of their aging status and contribute to an awareness that aging is a phase of psychological loss rather than a psychological growth [22]. It needs to be noted that this study provides formidable empirical evidence to examine the mediating effect of the two dimensions of aging attitudes between traumatic events and depression, which facilitates the non-Western aging research.

As predicted, in addition to indicating the mediating role of attitudes towards aging, this study further demonstrates that positive aging attitudes could buffer the negative effects of traumatic events on depression while negative aging attitudes would strengthen the harmful impacts of traumatic exposure on depression. This study responds to the controversy in previous empirical studies and proves the moderating effects of positive aging attitudes and negative aging attitudes [22,32,34]. To illustrate, older adults with positive aging attitudes may take more active responses and maintain optimistic approaches when being exposed to traumatic events, which reduces the possibility of depression [19]. In contrast, elderly who hold negative attitudes towards aging tend to have pessimistic views and are more vulnerable to being impaired, which contributes to the experience of depression [23]. Moreover, our research broadens the applicability of the organism-environment interaction model because this model was scarcely conducted in gerontology studies [31,32].

Furthermore, this research underlines the significance of distinguishing positive aging attitudes and negative aging attitudes because they are divergent notions [22]. To our knowledge, the present study is initial to examine two dimensions of aging attitudes both as mediators and moderators in the Chinese social context and fills the research gap. More crucially, our results show that negative aging attitudes have a stronger impact on depression when compared with positive aging attitudes. This pattern may reveal a phenomenon, that is, negative mental states may normally have greater impacts on depression than positive mental states [40]. Given this finding, the importance of reducing negative attitudes towards aging should be highlighted.

These findings indicated above are enlightening for social policymaking and social work intervention programs. Firstly, this study has recognized the deleterious impact of traumatic events on the elderly populace. The Chinese government should strengthen the prevention and detection of traumatic events in the elderly by distributing public health supports and resources [8]. Moreover, the treatment and therapy in the depression of Chinese older adults is worthy of attention. In the past, the mental health of the elderly Chinese population received little attention from society. In that vein, the Orientation Program designed by Piadehkouhsar et al. [41] was a successful intervention especially designed for elderly individuals, which could be utilized by geriatric social workers and psychotherapists. Furthermore, since two dimensions of aging attitudes were validated as mediators between traumatic events and depression, it seems that facilitating positive aging attitudes and lessening negative aging attitudes may be regarded as unique intervention paths. Our results has suggested that an individual’s attitude should be highlighted because counsellors and clinicians have not fully considered it before. Taking AGNES intervention as an example, fostering positive aging attitudes, and avoiding negative aging attitudes can be adopted as psychotherapeutic programs to help older adults cope better with trauma and adversities by psychological professionals [42].

5 Limitation and Future Direction

It should be noted that there are some weaknesses in this study. Firstly, the current study is not allowed to draw the causal sequences due to the cross-sectional design. This means that the elderly’s depression may result in negative aging attitudes. Therefore, longitudinal studies and experimental designs should be applied to determine the causality. In addition, the present study only collected traumatic events that had happened in the past 12 months because of the limitation of the secondary data in CLASS. Future studies are encouraged to assess the duration and intensity of traumatic events through long-term follow-up. Last but not least, many other mental illnesses may also occur together with depressive symptoms after trauma exposure, such as anxiety and PTSD [14,43]. Accordingly, research on other psychological consequences after traumatic events among Chinese elderly should be conducted in the future.

Acknowledgement: Data used in this study were from the 2014 China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS) collected by the National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China (NSRC). The authors appreciate the assistance in providing data from the 2014 CLASS.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declare that he/she has no conflict of interest.

1. China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs (2016). Statistics bulletin of social service development. Social and Public Welfare, 7, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

2. Luijendijk, H. J., van den Berg, J. F., Dekker, M. J., van Tuijl, H. R., Otte, W. et al. (2008). Incidence and recurrence of late-life depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(12), 1394–1401. DOI 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Luppa, M., Sikorski, C., Luck, T., Ehreke, L., Konnopka, A. et al. (2012). Age-and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life-systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(3), 212–221. DOI 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dulin, P. L., Passmore, T. (2010). Avoidance of potentially traumatic stimuli mediates the relationship between accumulated lifetime trauma and late-life depression and anxiety. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(2), 296–299. DOI 10.1002/jts.20512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lim, M. L., Lim, D., Gwee, X., Nyunt, M. S. Z., Kumar, R. et al. (2015). Resilience, stressful life events, and depressive symptomatology among older Chinese adults. Aging & Mental Health, 19(11), 1005–1014. DOI 10.1080/13607863.2014.995591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hansen, M. C., Ghafoori, B., Diaz, M. (2020). Examining attitudes towards mental health treatment and experiences with trauma: Understanding the needs of trauma-exposed middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(5), 1452–1468. DOI 10.1002/jcop.22339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Perfect, M. M., Turley, M. R., Carlson, J. S., Yohanna, J., Saint Gilles, M. P. (2016). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015. School Mental Health, 8(1), 7–43. DOI 10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hamama-Raz, Y., Ben-Ezra, M., Lavenda, O. (2021). Factors associated with adjustment disorder-the different contribution of daily stressors and traumatic events and the mediating role of psychological well-being. Psychiatric Quarterly, 92(217), 217–227. DOI 10.1007/s11126-020-09779-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Katsumata, Y., Arai, A., Ishida, K., Tomimori, M., Lee, R. B. et al. (2012). Which categories of social and lifestyle activities moderate the association between negative life events and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults in Japan? International Psychogeriatrics, 24(2), 307–315. DOI 10.1017/S1041610211001736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Platt, J. M., Lowe, S. R., Galea, S., Norris, F. H., Koenen, K. C. (2016). A longitudinal study of the bidirectional relationship between social support and posttraumatic stress following a natural disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 29(3), 205–213. DOI 10.1002/jts.22092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Turner, R. J. (2013). Understanding health disparities: The relevance of the stress process model. Society and Mental Health, 3(3), 170–186. DOI 10.1177/2156869313488121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Krause, N. (2004). Lifetime trauma, emotional support, and life satisfaction among older adults. Gerontologist, 44(5), 615–623. DOI 10.1093/geront/44.5.615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Krause, N., Shaw, B. A., Cairney, J. (2004). A descriptive epidemiology of lifetime trauma and the physical health status of older adults. Psychology and Aging, 19(4), 637–648. DOI 10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chu, D. A., Williams, L. M., Harris, A. W., Bryant, R. A., Gatt, J. M. (2013). Early life trauma predicts self-reported levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms in nonclinical community adults: relative contributions of early life stressor types and adult trauma exposure. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(1), 23–32. DOI 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Williams, S. L., Williams, D. R., Stein, D. J., Seedat, S., Jackson, P. B. et al. (2007). Multiple traumatic events and psychological distress: The South Africa stress and health study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(5), 845–855. DOI 10.1002/jts.20252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Seplaki, C. L., Goldman, N., Weinstein, M., Lin, Y. H. (2006). Before and after the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake: Traumatic events and depressive symptoms in an older population. Social Science & Medicine, 62(12), 3121–3132. DOI 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang, M., Liu, J., Sun, Q., Zhu, W. (2019). Mechanisms of the formation and involuntary repetition of trauma-related flashback: A review of major theories of PTSD. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 21(3), 81–97. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2019.011010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Borges, G., Benjet, C., Medina-Mora, M. E., Orozco, R., Molnar, B. E. et al. (2008). Traumatic events and suicide-related outcomes among Mexico City adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(6), 654–666. DOI 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01868.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Laidlaw, K., Power, M. J., Schmidt, S. (2007). The Attitudes to Ageing Questionnaire (AAQDevelopment and psychometric properties. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(4), 367–379. DOI 10.1002/gps.1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bodner, E., Shrira, A., Bergman, Y. S., Cohen-Fridel, S., Grossman, E. S. (2015). The interaction between aging and death anxieties predicts ageism. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 15–19. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Quinn, K. M., Laidlaw, K., Murray, L. K. (2009). Older peoples’ attitudes to mental illness. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(1), 33–45. DOI 10.1002/cpp.598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bellingtier, J. A., Neupert, S. D. (2018). Negative aging attitudes predict greater reactivity to daily stressors in older adults. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(7), 1155–1159. DOI 10.1093/geronb/gbw086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lamont, R. A., Nelis, S. M., Quinn, C., Clare, L. (2017). Social support and attitudes to aging in later life. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 84(2), 109–125. DOI 10.1177/0091415016668351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Levy, B. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 18(6), 332–336. DOI 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Suh, S., Choi, H., Lee, C., Cha, M., Jo, I. (2012). Association between knowledge and attitude about aging and life satisfaction among older Koreans. Asian Nursing Research, 6(3), 96–101. DOI 10.1016/j.anr.2012.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Pikhartova, J., Bowling, A., Victor, C. (2015). Is loneliness in later life a self-fulfilling prophecy? Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 543–549. DOI 10.1080/13607863.2015.1023767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu, J., Wei, W., Peng, Q., Guo, Y. (2021). How does perceived health status affect depression in older adults? Roles of attitude toward aging and social support. Clinical Gerontologist, 44(2), 169–180. DOI 10.1080/07317115.2019.1655123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Eagly, A. H., Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. [Google Scholar]

29. O’Brien, E. L., Torres, G. E., Neupert, S. D. (2020). Cognitive interference in the context of daily stressors, daily awareness of age-related change, and general aging attitudes. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 20(3), 390. DOI 10.1093/geronb/gbaa155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Martin, A. V., Eglit, G. M., Maldonado, Y., Daly, R., Liu, J. et al. (2019). Attitude toward own aging among older adults: Implications for cancer prevention. The Gerontologist, 59(Supplement_1), S38–S49. DOI 10.1093/geront/gnz039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J., Theokas, C. (2006). Dynamics of individual←→ context relations in human development: A developmental systems perspective. In: Thomas, J. C., Segal, D. L., Hersen, M. (eds.Comprehensive handbook of personality and psycho-pathology, vol. 1. Personality and Everyday Functioning, pp. 23–43. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

32. Liu, J., Wei, W., Peng, Q., Xue, C. (2020). Perceived health and life satisfaction of elderly people: testing the moderating effects of social support, attitudes toward aging, and senior privilege. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 33(3), 144–154. DOI 10.1177/0891988719866926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Laidlaw, K. (2012). Are attitudes to ageing and wisdom enhancement legitimate targets for CBT for late life depression and anxiety? Nordic Psychology, 62(2), 27–42. DOI 10.1027/1901-2276/a000009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Levy, B. R., Hausdorff, J. M., Hencke, R., Wei, J. Y. (2000). Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self-stereotypes of aging. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55(4), 205–213. DOI 10.1093/geronb/55.4.P205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chen, L., Alston, M., Guo, W. (2019). The influence of social support on loneliness and depression among older elderly people in China: Coping styles as mediators. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(5), 1235–1245. DOI 10.1002/jcop.22185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric methods. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. [Google Scholar]

37. Li, C., Jiang, S., Li, N., Zhang, Q. (2018). Influence of social participation on life satisfaction and depression among Chinese elderly: Social support as a mediator. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(3), 345–355. DOI 10.1002/jcop.21944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Preacher, K. J., Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. DOI 10.3758/BF03206553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Toothaker, L. E., Aiken, L. S., West, S. G. (1994). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 45(1), 119. DOI 10.2307/2583960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mock, S. E., Eibach, R. P. (2011). Aging attitudes moderate the effect of subjective age on psychological well-being: Evidence from a 10-year longitudinal study. Psychology and Aging, 26(4), 979–986. DOI 10.1037/a0023877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Piadehkouhsar, M., Ahmadi, F., Khoshknab, M. F., asekhi, A. A. (2019). The effect of orientation program based on activities of daily living on depression, anxiety, and stress in the elderly. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 7(3), 170. DOI 10.30476/IJCBNM.2019.44992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Rantanen, T., Pynnönen, K., Saajanaho, M., Siltanen, S., Karavirta, L. et al. (2019). Individualized counselling for active aging: protocol of a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial among older people (the AGNES intervention study). BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 161. DOI 10.1186/s12877-018-1012-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Goldmann, E., Galea, S. (2014). Mental health consequences of disasters. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 169–183. DOI 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |