| International Journal of Mental Health Promotion |  |

DOI: 10.32604/IJMHP.2021.013518

ARTICLE

Voice More and Be Happier: How Employee Voice Influences Psychological Well-Being in the Workplace

1School of Political Science and Public Administration, Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430072, China

2School of Management, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, 430070, China

3School of Business, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

*Corresponding Author: Baoguo Xie. Email: xiebaoguo@foxmail.com

Received: 09 August 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020

Abstract: The recently recognized core construct of employee voice has been demonstrated to be related to various outcomes. However, to date, the impact of employee voice over time and on important employee well-being has been rarely tested. In the present research, we studied in particular how employee voice behavior is related to psychological well-being. Employing the theory of self-determination, we developed three hypotheses pertinent to this relationship, including the mediating role of authentic self-expression and the moderating role of collectivist orientation. We tested our hypotheses using data from 217 employees in Mainland China over two time periods. As we hypothesized, we found positive relationships between the employee voice and psychological well-being. Our results also verified that these relationships are fully mediated by authentic self-expression and partially moderated by collectivist orientation.

Keywords: Employee voice; psychological well-being; authentic self-expression; collectivist orientation

Employees’ psychological health recently emerged as an essential challenge in organizations. According to a recent study conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO), common mental diseases cost the global economy US$ 1 trillion each year in lost productivity [1]. In response to the large and growing health challenge posed by mental-related conditions, workplace health promotion is critical in maintaining and promoting psychological well-being among employees [2]. To data, academics, as well as practitioners in the field, mostly explored the personal disposition and the situational context influence how employees achieving psychological well-being in the workplace [3–5], the potential that employee behaviors show in creating positive changes in psychological well-being has so far been underexplored in research.

This study extends research on employee voice and psychological well-being by examining the relationship between these two variables. While both employee voice and psychological well-being have been the subject of considerable research, the potential link between voice behavior and psychological well-being has largely been neglected. Neglecting a potential relationship between these two variables is surprising for two reasons. First, employee voice has been shown to be positively related to organizational orientated outcomes, such as employee retention [6], engagement [7,8], and organizational commitment [9]. Second, psychological well-being is known to be a significant attitudinal variable associated with employee health and both job and organizational performance. For example, reviews of international research reveal considerable evidence (e.g., Harter et al. [10]) that employee well-being reliably predicts a range of organizational-level outcomes, including productivity, employee turnover and absenteeism, and financial performance [11].

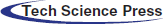

In this research, we aim to relate employee voice to psychological well-being. As such, we sought to fulfill three objectives: (1) To investigate the role of voice behavior on psychological well-being; (2) To test whether authentic self-expression mediates the relationship between voice behavior and psychological well-being; and (3) To investigate whether collectivist orientation moderates the relationship between voice behavior and psychological well-being. The second objective is based on previous research that has found a relationship between employee voice and self-expression [12] and between authenticity and psychological well-being [13]. Our third objective derives from the work of Rego et al. [14], who identified collectivist orientation as a possible individual-level antecedent of well-being but with mixed results. The present study contributes to the literature by examining empirically how employee voice is linked with psychological well-being using two-wave data from a large, representative sample of Chinese employees. The paper also makes important contributions to both theory and practice. First, it contributes to the theory because employee voice and psychological well-being are both pivotal to individual and organizational performance. Likewise, it contributes to practice because employer agency and human resource management strategy play key roles in formulating, implementing, and operating voice behavior and its subsequent impact on psychological well-being. The overall theoretical model is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Theoretical model

2 Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1 Employee Voice and Psychological Well-Being

Employee voice is defined as speaking up about ideas, concerns, information, or opinions about work-related issues [15]. As a specific type of extra-role behavior, employee voice involves “constructive, change-oriented communication intended to improve the situation” [16] (p. 326). Employee voice is already a well-established concern in human resource management literature [17]. During the past decade, scholars have found that employee voice is related to positive attitudes toward jobs and organizations [18]. However, as Nawakitphaitoon et al. [19] note, research on the effect of employee voice on desirable organizational outcomes has been widely studied in Western countries. Moreover, most research on employee voice behavior has explored the antecedent factors that encourage employees to speak up [20–22]. This perspective ignored the possibility that employees primarily use voice behavior to find meaning in work (e.g., psychological well-being) as well. Our concern is not with the causes of voice behavior, but rather with the outcomes, and in particular with the extent to which employee voice has an impact upon psychological well-being.

Psychological well-being is conceived in the extant literature as a foundational variable that influences individual and organizational outcomes. Definitions of psychological well-being vary, currently, several measures relate to different conceptual models, and most researchers agree that psychological well-being is best understood as a positive assessment of one’s work-life [23,24]. The relationship between psychological well-being and desirable organizational outcomes was clearly established [11,24,25]. As Deci et al. [26] note, a common thread is an assumption that happy workers have higher performance, with mutual benefits for employees and organizations. Hence, there is a growing need to understand what leads to psychological well-being entirely [4,5]. Psychological well-being has mainly been explained by organizational factors [4,27,28]. Consequently, we still know few about employee behaviors that could lead to psychological well-being. Amongst the employee behaviors, voice behavior has recently merged as the potential predictor of psychological well-being. Some studies showed empirical support for the positive link between voice behavior and psychological well-being [29], but the number remains limited. To our knowledge, no research on the relationship between voice behavior and psychological well-being has been made amongst Chinese employees. Not taking into account this perspective could lead to a restrictive view of psychological well-being and limit the scope of the findings.

Self-determination theory (SDT) argues that the importance of the satisfaction of basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness in one’s growth and integrity [30]. Autonomy refers to one’s need to experience volition and psychological freedom; competence refers to one’s need to master the environment to realize desired outcomes; relatedness refers to one’s need to securely connected to and cared by others. According to SDT, the satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs leads to an individual’s optimal functioning. Conversely, frustration in meeting the three needs results in energy depletion and impaired functioning. From SDT perspective, we argue that voice behavior might be perceived as a way for employees to meet their psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, resulting in a positive relationship between voice behavior and psychological well-being. However, it is essential to consider the mediating mechanisms underlying this relationship to provide a robust theoretical explanation as to why and how this voice behavior might promote employees’ psychological well-being. To this end, drawing on SDT, we identified authentic self-expression as a critical psychological process that likely mediates the beneficial effects of voice behavior on psychological well-being.

As the voice literature is dominated by studies that view voice behavior as a means for the purpose of organizational improvement, little is considering voice behavior as an expression of employees’ self-determination. From SDT, we emphasize that employees are doing voice behavior because they derive spontaneous satisfaction from the voice itself. First, voice behavior is a discretionary behavior, employees are doing this activity wholly volitionally, and they can choose whether to engage in at any particular moment [31]. Thus, voice can serve to meet the autonomous needs. Second, voice behavior can enhance employees’ feelings of control over their work environment, so they have a conviction that they can shape what will happen in the workplace [32]. Voice behavior is found to have both a direct impact and an indirect impact on levels of employee engagement [7] and is likely to increase employees’ job proficiency and lead to career progression (e.g., promotions and salary progression) [33]. Therefore, voice behavior makes employees experience the satisfaction of the needs for competence. Third, employees can receive help from leaders and build a better relationship with authority figures by giving voice [34], which also helps to satisfy the needs to be connected to others. The SDT postulates that satisfaction of the three basic needs provides the nutriments for intrinsic motivation, optimal human development, and integrity, subsequent research has confirmed that each of the three needs does indeed predict psychological well-being in a variety of countries [35]. These arguments lead to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Employee voice is positively related to psychological well-being.

Authentic self-expression refers to one’s behavior being consistent with his/her values, preferences, and needs [36]. According to SDT, voice behavior is not only as a means to regulate the quality of their social exchange with positive work environment [34], but also an expression of employees’ desire and choice to communicate concerns and complains for the benefits of the organizations [37]. As Wilkinson and Dundon [38] note, voice is “the ways and means through which employees attempt to have a say and potentially influence organizational affairs about issues that affect their work and the interests of managers and owners” (P. 5). In this definition, voice behavior is regarded as how employees have to say in work activities and decision-making and involves a manifestation of authenticity [39], including self-determining efforts to identify and express themselves. Through voice, employees harness their selves within their work roles, they become more authentic by displaying their opinions in organizations. Therefore, we expect that employees express more authentic selves when they use voice to share suggestions of how to improve organizational functioning.

We further argue that authentic self-expression might increase psychological well-being. According to SDT, authentic self-expression is any self-aspect that feels internally caused and self-determined, which is in concordance with intrinsic basic psychological needs of competency, autonomy, and relatedness [40]. A variety of psychological perspectives suggest that a happy and meaningful life is the product of acting in accord with one’s self. Both theoretical and empirical evidence support the role of authentic self-expression in psychological health. Most frequently, this work has demonstrated the relationship between authentic self-expression and psychological well-being. For example, a laboratory experiment by Cable et al. [41] revealed that socialization emphasizing newcomers’ authentic self-expression leads to significantly higher employee engagement and job satisfaction. Other studies using similar measures of authenticity examined the importance of the authentic self-expression to psychological functioning [40,42]. Because when people think about their true selves, they feel a greater increase in self-esteem. Moreover, the choices and actions consistent with one’s true self lead to a more excellent feeling of meaning and satisfaction [43]. Hence, the closer employees feel to their true selves in the workplace, the more likely they are to report higher psychological well-being. According to the theoretical relationships between voice behavior, authentic self-expression, and psychological well-being, we hypothesized a mediation model:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Authentic self-expression mediates the effects of employee voice on subsequent psychological well-being.

To further illustrate the self-determination process underlying the relationship between voice behavior and psychological well-being, we introduce collectivist orientation as a moderator. Cross-cultural studies have established that congruence between employees’ cultural values and work behaviors is fundamental to their psychological well-being, as the unique norms and values inherent in cultures affect the way employees are motivated [44–46]. Here, we expect that employees with different collectivist values are expected to differ in the way they perceive voice behavior in relation to their psychological well-being. Collectivist orientation, as a set of cultural values and norms, emphasizes interdependence, harmony, cooperation, and social obligation [47]. Individuals with a collectivist orientation are more aligned with in-groups’ goals as opposed to an individual-based perspective [48]. Thus, collectivist orientation influences employees’ work values and expectations, and that, in turn, affect their interpretation of voice behavior. High collectivist employees may attach more meaning to voice behavior based on their cultural orientations. For high collectivists, voice behavior is not viewed as a means of communicating with management but embedded in relationship contexts. They are motivated by relational oriented voice factors, such as group relationships and harmony. Besides, collectivists are more motivated to seek to protect the group welfare. When they can derive meaning from their voice, they will be motivated, and a higher level of psychological well-being will be resulted. As a result, employees with high versus low collectivist orientation should differ in their interpretations of voice and its effects. That is, the collectivist orientation will strengthen the impact of voice behavior on psychological well-being. Based on the above arguments, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The positive relationship between voice behavior and psychological well-being will be higher when employees are with a collectivist orientation.

3.1 Participants and Procedures

We collected our data in two waves to alleviate concerns about common method variance [49]. At time 1, we distributed 400 surveys measuring employee voice behavior, collectivist orientation, and authentic self-expression to one big company in Mainland China. In total, 310 surveys were returned. Two months later (Time 2), we sent a second questionnaire measuring psychological well-being to the first wave respondents. Of these, 280 were returned. In total, after eliminating data from any respondent who failed to complete both questionnaires, we received two waves of usable surveys from 217 respondents. There were no significant differences for the characteristics (gender, tenure, education, age) between participants who completed the whole questionnaires and those who chose not to continue. The two-month interval between waves of data collection was chosen to provide enough time to minimize common method error variance, yet not so long a time period as to make the recall of events that affect one’s perceptions difficult [50]. Assessments of authentic self-expression and psychological well-being are important perceptions, which are not likely to be clouded by everyday activities.

The participants were employed in a variety of job types, such as clerical work, management, technical work, and marketing. Females comprised 19% of the respondents. With respect to education, 34.6% had graduate degrees, 47.4% had bachelor’s degrees, and 18% had a master’s degree. In addition, 67.8% of our sample had one year with the same organization, which 19.8% had 2–3 years, and 12.4% had more than three years of experience within their current employer.

Our instruments were designed to capture the four concepts being investigated in this research: (1) Employee voice, (2) Authentic self-expression, (3) Collectivist orientation, and (4) Psychological well-being. All of the items measuring these four concepts were responded by using five-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

We adopted Farh et al. [51]’ s the two-item scale to measure employee voice behavior at Time 1. This scale is frequently and shows strong reliability. Sample items are “Actively brings forward suggestions that may help the organization run more efficiently or effectively,” and “Actively raises suggestions to improve work procedures or processes” (α = 0.79).

3.2.2 Authentic Self-Expression

Following Cable et al. [41]’ s research, we assessed authentic self-expression at Time1 using a six-item scale. Sample items include “In this job, I can be who I really I am,” “In this job, I feel authentic,” and “In this job, I don’t feel I need to hide who I really am” (α = 0.91).

3.2.3 Collectivist Orientation

We measured collectivist orientation at Time 1 by using two items developed by Dorfman et al. [52]. The sample items include “It is more important for a manager to encourage loyalty and a sense of duty in his/her subordinates than it is to encourage individual initiative,” and “Group success is more important than individual success” (α = 0.71).

3.2.4 Psychological Well-Being

We measured psychological well-being at Time 2 with Brunetto et al. [53]’ s a four-item scale. Sample items include “Overall, I think I am reasonably satisfied with my work life,” and “Overall, most days I feel a sense of accomplishment in what I do” (α = 0.85).

We also collected data at Time 1 on four demographic variables: Age, gender, education level, and job types. These variables were chosen because they reflect individual-level factors related to psychological well-being [54–57]. Age was divided into three categories: Under 30 years, 31–40, and over 40. Education was grouped into three categories: graduate degree, bachelor’s degree, and master’s degree or above, while job types in the organization was grouped according to whether the participant occupied a clerical work, management, technical work, marketing, or other types of work.

As participants in this study were working in one company, it was possible that the nested data were non-independent. We first conducted Harman’s single-factor test and examined the Common method bias (CMB). Afterward, hierarchical multiple regression and PROCESS were applied to test Hypotheses.

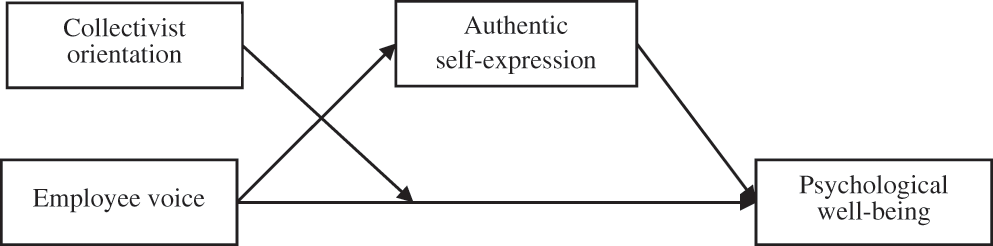

Common method bias (CMB) should be considered since voice behavior, authentic self-expression, collectivist orientation, and psychological well-being were collected from one source. Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to check the problem of CMB. The results indicated that all the measurement items were divided into four constructs with eigenvalues higher than 1. These four constructs account for 75.04% of the variance, with the first factor explaining less than 41.60%, which is less than the threshold value of 50% [58]. CMB exists when the study variables have higher inter-correlations (r > 0.90) among them [59]. As shown in Tab. 1, the findings did not state the higher inter-correlations among study variables, thereby indicating that CMB is minimized in the current study. Based on the analyses mentioned above, the dataset was appropriate for further analysis.

Tab. 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations, while Tab. 2 reports the results of our hypothesis testing. Results showed that employee voice positively correlated with psychological well-being (r = 0.22, p < 0.01), and authentic self-expression (r = 0.61, p < 0.01). authentic self-expression positively correlated with psychological well-being (r = 0.30, p < 0.01). These results are in the expected direction and support the positive relationships between employee voice, authentic self-expression, and psychological well-being. As recommended by Bernerth et al. [60], we analyzed whether it was necessary to control for gender, age, education, and job types. The results show that these variables did not significantly relate to psychological well-being, so we did not control for these socio-demographic variables when testing our hypotheses.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics and correlations matrix of study variables

We employed hierarchical regression and bootstrapping [61] to establish the impact of the employee voice on their psychological well-being, the mediating role of authentic self-expression, and the moderating role of collectivist orientation.

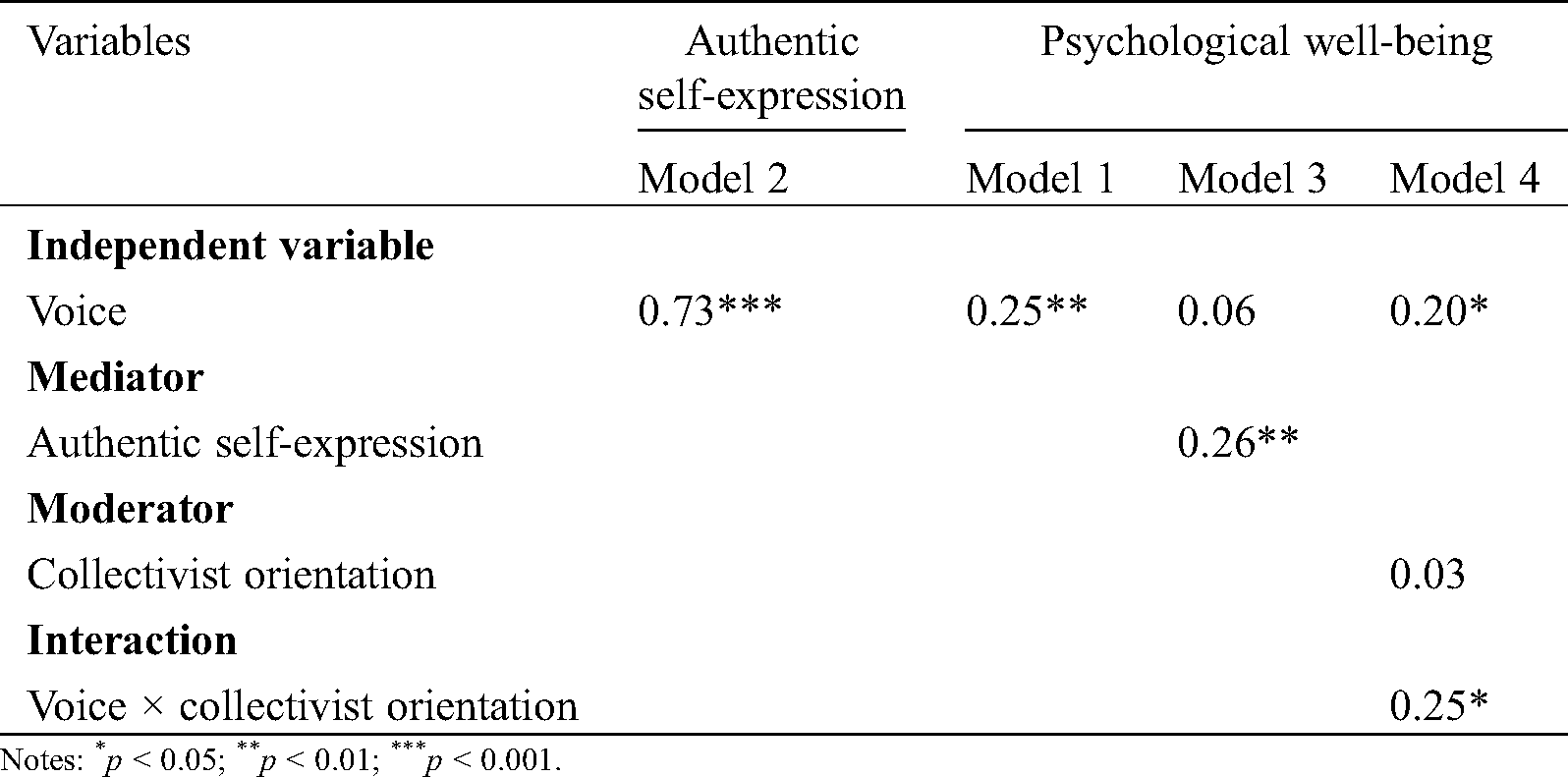

H1 proposed that employee voice is positively related to psychological well-being. We tested our hypothesis using a hierarchical analysis run by SPSS. In Model 1 of Tab. 2, the results show that employee voice is positively related to psychological well-being (B = 0.25, p < 0.01). Thus, H1 is supported.

H2 argued that authentic self-expression mediated the relationship between employee voice and psychological well-being. To examine the mediation hypotheses, the PROCESS mediation macro developed by Preacher et al. [61] was used. As shown in Models 1–3, first, we examined the relationship between employee voice and authentic self-expression. The results show that employee voice (B = 0.73, p < 0.001) was a significant predictor of authentic self-expression. Second, when employee voice and authentic self-expression were entered simultaneously, the presence of authentic self-expression eliminated the relationships between voice behavior and psychological well-being. We further assessed the mediation using the bootstrapping procedure by SPSS Macro Syntax file, since it is more powerful than the causal steps approach using hierarchical regression [61], we estimated 5000 bootstrap samples; independent variables comprised the voice behavior, the mediator was authentic self-expression, and the dependent variable was psychological well-being. The indirect effect of voice behavior on psychological well-being was 0.19 (p < 0.05), with a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI of [0.07,0.32]. This provides support for Hypothesis 2.

Table 2: The regression of voice on authentic self-expression and psychological well-being

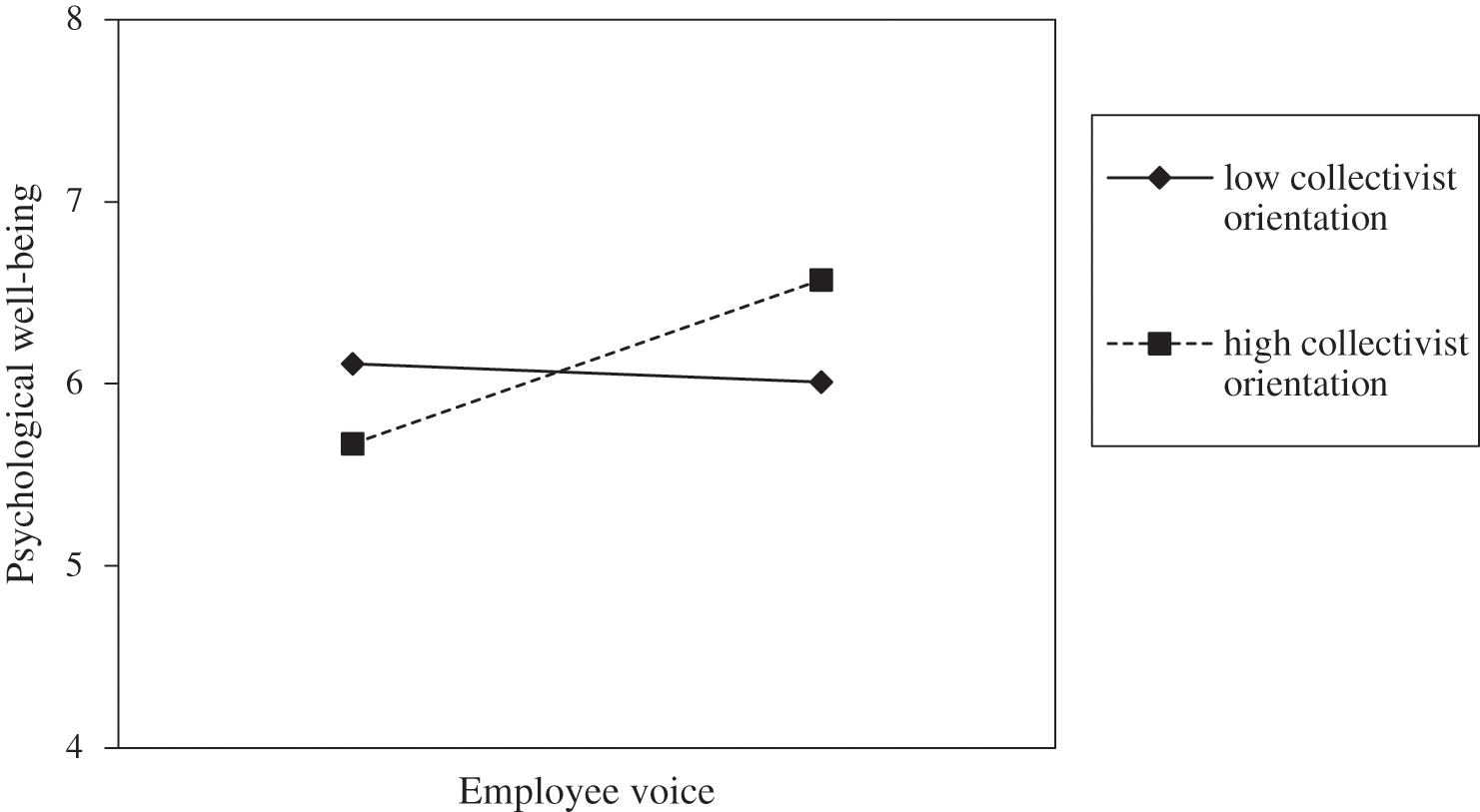

Figure 2: Collectivist orientation as the moderator of the relationship between employee voice and psychological well-being

H3 proposed that collectivist orientation moderated the relationship between employee voice and psychological well-being. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, collectivist orientation and voice behavior showed a significant interaction on psychological well-being (see Model 4). Further tests of the moderating role of collectivist orientation using the PROCESS bootstrapping approach proposed by Hayes [62] showed that the effects of employee voice on psychological well-being significantly vary between the high and low levels of collectivist orientation, suggesting that the effects of voice behavior on psychological well-being were smaller at a low level of collectivist orientation (r = 0.12, ns) than the effects at a high level of collectivist orientation (r = 0.46, p < 0.01), further supporting H3. To clearly illustrate the moderation effects, we plotted the interaction at one standard deviation below and above the mean of the moderator. As seen in Fig. 2, the effect of voice behavior on psychological well-being was stronger for employees with high collectivism.

There has been growing interest in understanding the antecedents of employee well-being (e.g., Guest [63]). The primary goal of this study was to expand this field of research by examining how employee voice affects psychological well-being. Using data from 217 employees from one big company, our results fully supported our hypotheses. As predicted, voice behavior positively affected authentic self-expression, which, in turn, impacted their psychological well-being. Besides, the effect of voice behavior on psychological well-being was stronger when employee collectivism was high or when collectivism was low. We discuss the implications of these findings.

Our study contributes to research on voice and psychological well-being in several ways. First, we extended the criterion space of voice research to include psychological well-being. Prior research has largely focused on studying performance, justice perception, job attitudes, and relational outcomes to indicate how employees use voice to arrive at outcomes [64]. Although the traditionally considered outcomes are undoubted of great importance, such a focus does not wholly recognize that employees also personally value voice behavior and fully accept its relevance for their well-being. Drawing on SDT, our findings suggest that employee voice may influence their psychological well-being through the satisfaction of the basic psychological needs for competency, autonomy, and relatedness. This result is analogous to Holland et al. [65]’ s finding that voice behavior is related to job satisfaction but extends these findings specifically to psychological well-being. Our study provides empirical evidence regarding the self-determining process of voice to enhance our understanding of the voice behavior on employees’ occupational health. Thus, there is significant value in incorporating constructs such as psychological well-being into new and existing models of voice behavior.

Second, our study also offers insight into the mediating mechanism that may underlie these effects. Although voice theory posits motivation as a possible mechanism of how voice influence employees’ outcomes [9], limited evidence exists on the mechanism through which voice is related to desirable outcomes. Our results suggest that voice behavior may influence psychological well-being through the mediating role of authentic self-expression. As employees feel authentic through voice behaviors, they benefit psychologically. This holds across time and extends Wood et al. [66]’s finding that psychological well-being is influenced by employees’ perception of expressing their concerns and ideas for improvement. Moreover, although authentic self-expression has been sometimes discussed in terms of authenticity and is understood as the degree to which one presents true self to others, our research is the first to provide direct evidence linking voice behavior and authentic self-expression. The finding highlights the positive bond between voice behavior and psychological well-being through a sense of authentic self-expression and opens new avenues for theorizing about differences in psychological well-being and could spark further research on authenticity displays.

Third, we found that collectivist orientation did moderate the relationship between voice behavior and psychological well-being. More specifically, when employees with high collectivism engage in voice behavior, they will perceive a higher level of psychological well-being. Despite voice’s potential benefits, studies of voice are somewhat limited in Western cultures. Besides, voice is an extra-role behavior that is not universally embraced by all cultures [31]. Our results show that the effects of voice behavior on psychological well-being vary according to an individual’s collectivist orientation and highlight the fact that voice behavior considered as effective in one country may not be suitable in another cultural setting. As noted above, this finding does provide support to Kwon et al. [67] and Li et al. [68]’ s arguments that different dimensions of culture, including collectivism, can moderate the nature of voice behavior and its antecedents and consequences. By incorporating cultural factors as a contingency to the influence of voice behavior, our findings alert future research on the potential impacts of cultural values on the effectiveness of voice behavior.

Our findings have important implications for managers who are interested in fostering employee psychological well-being. First, our results suggest that voice behavior is a viable way that should be considered by managers seeking to increase employees’ well-being in the workplace. In this respect, managers should make their best effort to encourage employees to provide comments or suggestions on improving organizational competitiveness. Doing so should enable employees to connect their voice behavior with the well-being in the workplace. Also, the finding of a mediating effect of authentic self-expression suggests that managers should encourage employees to achieve full expression of themselves to find meaning and purpose in their work. Finally, our results regarding the moderating role of collectivist orientation that fostering the collectivist culture may be necessary for organizations to maximize the impact of employee voice on psychological well-being.

6 Limitations and Future Research

Our findings must be viewed in light of four limitations. First, all our data were self-reported. Although a majority of the studies on voice behavior and psychological well-being rely on self-report measures, alternative forms of data collection using leader and coworker ratings could further minimize the problem of common method bias [34]. Second, we utilized Chinese samples, making it unclear whether our results are generalizable to other countries with different cultures. Previous research has suggested the mean and variance levels in well-being may be lower in collectivist culture because higher levels of collectivism make the Chinese employees more hesitant to express their true selves [69]. Therefore, testing these hypotheses in an individualistic culture would provide more information regarding its generalizability. Third, because participants were from one organization, we were unable to control other contextual factors that might affect the relationship uncovered in this study. For example, organizational culture, workgroup climate, and leadership associated with psychological well-being may shape the magnitude and nature of the effect of employee voice on psychological well-being. Moreover, other individual difference variables may also affect the relationship between employee voice and psychological well-being. In this respect, previous research has shown personality and personal resources to be related to well-being [5,70,71]. Research on how these and other individual-level factors affect the employee voice–psychological well-being relationship is another avenue for future research. Forth, we examined the role of authentic self-expression as a mediator of the relationship between employee voice and psychological well-being. While authentic self-expression is a logical measure of self-determination, there are other forms of psychological self-determination, such as intrinsic motives [72], that may enhance or substitute for the role played by authentic self-expression. Future studies however could consider replicating our results using a more objective measure of self-determination in other contexts.

Funding Statement: This project was supported by MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences, Grant No. 19YJC630190, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Grant No. 1203-413000068/2020AI010.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. World Health Organization. (2019). Making the investment case for mental health: A WHO (No. WHO/UHC/CD-NCD/19.97). Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

2. Rongen, A., Robroek, S. J., van Lenthe, F. J., Burdorf, A. (2013). Workplace health promotion: A meta-analysis of effectiveness. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(4), 406–415. DOI 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xin, L., Li, M., Tang, F., Zhou, W., Zheng, X. (2018). Promoting employees’ affective well-being: Comparing the impact of career success criteria clarity and career decision-making self-efficacy. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 20(2), 55–65. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2018.010723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xu, J., Xie, B., Tang, B. (2020). Guanxi hrm practice and employees’ occupational well-being in china: A multi-level psychological process. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2403. DOI 10.3390/ijerph17072403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xin, L., Li, M., Tang, F., Zhou, W., Wang, W. (2019). How does proactive personality promote affective well-being? A chained mediation model. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 21(1), 1–11. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2019.010808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Spencer, D. G. (1986). Employee voice and employee retention. Academy of Management Journal, 29(3), 488–502. [Google Scholar]

7. Rees, C., Alfes, K., Gatenby, M. (2013). Employee voice and engagement: Connections and consequences. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(14), 2780–2798. DOI 10.1080/09585192.2013.763843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ruck, K., Welch, M., Menara, B. (2017). Employee voice: An antecedent to organizational engagement? Public Relations Review, 43(5), 904–914. DOI 10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.04.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Farndale, E., Van Ruiten, J., Kelliher, C., Hope-Hailey, V. (2011). The influence of perceived employee voice on organizational commitment: An exchange perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 50(1), 113–129. DOI 10.1002/hrm.20404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., Keyes, C. L. (2003). Well-Being in the Workplace and its Relationship to Business Outcomes: A Review of the Gallup Studies. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

11. Wright, T. A. (2010). Much more than meets the eye: The role of psychological well-being in job performance, employee retention and cardiovascular health. Organizational Dynamics, 39(1), 13–23. DOI 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2009.10.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xue, X., Song, H. Y., Tang, Y. J. (2015). The relationship between political skill and employee voice behavior from an impression management perspective. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 31(5), 1877–1888. DOI 10.19030/jabr.v31i5.9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Goldman, B. M., Kernis, M. H. (2002). The role of authenticity in healthy psychological functioning and subjective well-being. Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association, 5(6), 18–20. [Google Scholar]

14. Rego, A., Cunha, M. P. (2009). How individualism–collectivism orientations predict happiness in a collectivistic context. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(1), 19–35. DOI 10.1007/s10902-007-9059-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dyne, L. V., Ang, S., Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392. DOI 10.1111/1467-6486.00384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Van Dyne, L., LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108–119. [Google Scholar]

17. Liu, W., Zhu, R., Yang, Y. (2010). I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 189–202. DOI 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.10.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mowbray, P. K., Wilkinson, A., Tse, H. H. (2015). An integrative review of employee voice: Identifying a common conceptualization and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(3), 382–400. DOI 10.1111/ijmr.12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Nawakitphaitoon, K., Zhang, W. (2020). The effect of direct and representative employee voice on job satisfaction in china: Evidence from employer-employee matched data. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31, 1–27. DOI 10.1080/09585192.2020.1744028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Duan, J., Li, C., Xu, Y., Wu, C. H. (2017). Transformational leadership and employee voice behavior: A Pygmalion mechanism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(5), 650–670. DOI 10.1002/job.2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xu, M., Qin, X., Dust, S. B., DiRenzo, M. S. (2019). Supervisor-subordinate proactive personality congruence and psychological safety: A signaling theory approach to employee voice behavior. Leadership Quarterly, 30(4), 440–453. DOI 10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang, G., Chen, S., Fan, Y., Dong, Y. (2019). Influence of leaders’ loneliness on voice-taking: The role of social self-efficacy and performance pressure. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 21(1), 13–29. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2019.010730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Warr, P. B. (1999). Well-being and the workplace. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

24. Xu, J., Xie, B., Chung, B. (2019). Bridging the gap between affective well-being and organizational citizenship behavior: The role of work engagement and collectivist orientation. International Journal of Environmental Research Public and Health, 16(22), 4503. DOI 10.3390/ijerph16224503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Eid, M., Larsen, R. J. (2008). The science of subjective well-being. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

26. Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 1–11. DOI 10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Huhtala, M., Feldt, T., Lämsä, A. M., Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U. (2011). Does the ethical culture of organizations promote managers’ occupational well-being? Investigating indirect links via ethical strain. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(2), 231–247. DOI 10.1007/s10551-010-0719-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhao, Y., Xie, B., Jin, W. (2018). The influence of supervisor’s transformational leadership and followers’ occupational well-being: A dual pathway model from a conservation of resources theory. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 20(1), 15–26. DOI 10.32604/IJMHP.2018.010747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Avey, J. B., Wernsing, T. S., Palanski, M. E. (2012). Exploring the process of ethical leadership: The mediating role of employee voice and psychological ownership. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(1), 21–34. DOI 10.1007/s10551-012-1298-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. DOI 10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412. DOI 10.5465/19416520.2011.574506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tangirala, S., Ramanujam, R. (2008). Employee silence on critical work issues: The cross-level effects of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology, 61(1), 37–68. DOI 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00105.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., Crant, J. M. (2001). What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Personnel Psychology, 54(4), 845–874. DOI 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00234.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ng, T. W. H., Feldman, D. C. (2012). Employee voice behavior: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 216–234. DOI 10.1002/job.754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182–185. DOI 10.1037/a0012801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kernis, M. H., Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 283–357. [Google Scholar]

37. Barry, M., Wilkinson, A. (2016). Pro-social or pro-management? A critique of the conception of employee voice as a pro-social behaviour within organizational behaviour. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 54(2), 261–284. DOI 10.1111/bjir.12114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wilkinson, A., Dundon, T., Donaghey, J., Freeman, R. (2014). The handbook of research on employee voice. Cheltenham: Editor Elgar Press. [Google Scholar]

39. Hsiung, H. H. (2012). Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: A multi-level psychological process. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(3), 349–361. DOI 10.1007/s10551-011-1043-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ménard, J., Brunet, L. (2011). Authenticity and well-being in the workplace: A mediation model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26(4), 331–346. DOI 10.1108/02683941111124854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Cable, D. M., Gino, F., Staats, B. R. (2013). Breaking them in or eliciting their best? Reframing socialization around newcomers’ authentic self-expression. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(1), 1–36. DOI 10.1177/0001839213477098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Womick, J., Foltz, R. M., King, L. A. (2019). Releasing the beast within? Authenticity, well-being, and the dark tetrad. Personality and Individual Differences, 137, 115–125. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2018.08.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Schlegel, R. J., Hicks, J. A. (2011). The true self and psychological health: Emerging evidence and future directions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(12), 989–1003. DOI 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00401.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ahuvia, A. C. (2002). Individualism/collectivism and cultures of happiness: A theoretical conjecture on the relationship between consumption, culture and subjective well-being at the national level. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 23–36. DOI 10.1023/A:1015682121103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Steele, L. G., Lynch, S. M. (2013). The pursuit of happiness in china: Individualism, collectivism, and subjective well-being during china’s economic and social transformation. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 441–451. DOI 10.1007/s11205-012-0154-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Krys, K., Zelenski, J. M., Capaldi, C. A., Park, J. Tilburg, W. et al. (2019). Putting the “we” into well-being: Using collectivism-themed measures of well-being attenuates well-being’s association with individualism. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 22(3), 256–267. DOI 10.1111/ajsp.12364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wagner, J. A., Moch, M. K. (1986). Individualism-collectivism: Concept and measure. Group & Organization Management, 11(3), 280–304. DOI 10.1177/105960118601100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Triandis, H. C. (2018). Individualism and Collectivism. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

49. Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. DOI 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Chen, G., Ployhart, R. E., Thomas, H. C., Anderson, N., Bliese, P. D. (2011). The power of momentum: A new model of dynamic relationships between job satisfaction change and turnover intentions. Academy of Management Journal, 54(1), 159–181. DOI 10.5465/amj.2011.59215089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Farh, J. L., Zhong, C. B., Organ, D. W. (2004). Organizational citizenship behavior in the people’s Republic of China. Organization Science, 15(2), 241–253. DOI 10.1287/orsc.1030.0051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Dorfman, P. W., Howell, J. P. (1988). Dimensions of national culture and effective leadership patterns: Hofstede Revisited. In: Farmer, R. N., Goun, E. G., (eds.Advances in international comparative management. New York: JAI Press, 127–150. [Google Scholar]

53. Brunetto, Y., Farr-Wharton, R., Shacklock, K. (2011). Using the Harvard HRM model to conceptualise the impact of changes to supervision upon HRM outcomes for different types of Australian public sector employees. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(3), 553–573. DOI 10.1080/09585192.2011.543633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Shokri, O., Tajik Esmaeili, A. A., Daneshvarpour, Z., Ghanaei, Z., Dastjerdi, R. (2007). Individual difference in identity styles and psychological well-being: The role of commitment. Advances in Cognitive Science, 9(2), 33–46. [Google Scholar]

55. Pinquart, M., Sorensen, S. (2001). Gender differences in self-concept and psychological well-being in old age: A meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(4), P195–P213. DOI 10.1093/geronb/56.4.P195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Witter, R. A., Okun, M. A., Stock, W. A., Haring, M. J. (1984). Education and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 6(2), 165–173. DOI 10.3102/01623737006002165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Cuyper, N., Witte, H. (2006). The impact of job insecurity and contract type on attitudes, well-being and behavioural reports: A psychological contract perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(3), 395–409. DOI 10.1348/096317905X53660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago press. [Google Scholar]

59. Pavlou, P. A., El Sawy, O. A. (2006). From it leveraging competence to competitive advantage in turbulent environments: The case of new product development. Information Systems Research, 17(3), 198–227. DOI 10.1287/isre.1060.0094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Bernerth, J. B., Cole, M. S., Taylor, E. C., Walker, H. J. (2018). Control variables in leadership research: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Management Development, 44(1), 131–160. [Google Scholar]

61. Preacher, K. J., Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. DOI 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Journal of Educational Measurement, 51(3), 335–337. [Google Scholar]

63. Guest, D. E. (2017). Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 22–38. DOI 10.1111/1748-8583.12139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Bashshur, M. R., Oc, B. (2015). When voice matters: A multilevel review of the impact of voice in organizations. Journal of Management Development, 41(5), 1530–1554. [Google Scholar]

65. Holland, P., Pyman, A., Cooper, B. K., Teicher, J. (2011). Employee voice and job satisfaction in Australia: The centrality of direct voice. Human Resource Management Journal, 50(1), 95–111. DOI 10.1002/hrm.20406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Wood, S., de Menezes, L. M. (2011). High involvement management, high-performance work systems and well-being. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(07), 1586–1610. DOI 10.1080/09585192.2011.561967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Kwon, B., Farndale, E. (2020). Employee voice viewed through a cross-cultural lens. Human Resource Management Review, 30(1), 100653. DOI 10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Li, Y., Sun, J. M. (2015). Traditional Chinese leadership and employee voice behavior: A cross-level examination. Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 172–189. DOI 10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Rothman, N. B., Magee, J. C. (2016). Affective expressions in groups and inferences about members' relational well-being: The effects of socially engaging and disengaging emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 30(1), 150–166. DOI 10.1080/02699931.2015.1020050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Austin, E. J., Saklofske, D. H., Egan, V. (2005). Personality, well-being and health correlates of trait emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(3), 547–558. DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Bermejo-Toro, L., Prieto-Ursúa, M., Hernández, V. (2016). Towards a model of teacher well-being: Personal and job resources involved in teacher burnout and engagement. Educational Psychology, 36(3), 481–501. DOI 10.1080/01443410.2015.1005006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. DOI 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |