Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Improved Hyperplane Assisted Multiobjective Optimization for Distributed Hybrid Flow Shop Scheduling Problem in Glass Manufacturing Systems

1 College of Computer Science, Liaocheng University, Liaocheng, 252059, China

2 School of Information Science and Engineering, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, 25014, China

* Corresponding Author: Junqing Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Hybrid Intelligent Methods for Forecasting in Resources and Energy Field)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2023, 134(1), 241-266. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2022.020307

Received 16 November 2021; Accepted 11 February 2022; Issue published 24 August 2022

Abstract

To solve the distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling problem (DHFS) in raw glass manufacturing systems, we investigated an improved hyperplane assisted evolutionary algorithm (IhpaEA). Two objectives are simultaneously considered, namely, the maximum completion time and the total energy consumptions. Firstly, each solution is encoded by a three-dimensional vector, i.e., factory assignment, scheduling, and machine assignment. Subsequently, an efficient initialization strategy embeds two heuristics are developed, which can increase the diversity of the population. Then, to improve the global search abilities, a Pareto-based crossover operator is designed to take more advantage of non-dominated solutions. Furthermore, a local search heuristic based on three parts encoding is embedded to enhance the searching performance. To enhance the local search abilities, the cooperation of the search operator is designed to obtain better non-dominated solutions. Finally, the experimental results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm is more efficient than the other three state-of-the-art algorithms. The results show that the Pareto optimal solution set obtained by the improved algorithm is superior to that of the traditional multiobjective algorithm in terms of diversity and convergence of the solution.Keywords

The hybrid flow shop scheduling problem (HFS) has been investigated and employed in lots of realistic industrial applications [1], such as glass-making systems [1–3] and steelmaking systems [4]. In the classical HFS process, there are several jobs, machines, and stages. A certain number of parallel machines are in each stage, where each arriving job should choose exactly one available machine. And each job follows the same processing route with machine selection flexibility. Therefore, compared with the classical flow shop scheduling problem, in HFS, an additional task is selected to suit machines for each operation, which has been proven to be an NP-hard problem [1].

With the development of industries, more and more researches have focused on distributed scheduling problem, including the distributed flow shop scheduling problem (DFSSP) [5], as well as distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling problem (DHFS) [6]. However, there is less literature for DHFS, compared with the works in solving flow shop or distributed flow shop. Pan et al. [7] studied a distributed flowshop group scheduling problem (DFGSP), where the families are considered in manufacturing cells. Huang et al. [8] proposed three constructive heuristics and an effective discrete artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm to solve the distributed permutation flowshop scheduling problem. Meng et al. [9] introduced the lot-streaming and carryover sequence-dependent setup time in the distributed permutation flowshop scheduling problem (DPFSP) with non-identical factories. Ying et al. [10] developed a hybrid algorithm with three versions of iterated greedy (IG) algorithm in order to minimize the makespan of the DHFS. Hao et al. [11] considered a DHFS with a brain storm optimization (BSO) algorithm, where the makespan is minimized. Cai et al. [12] proposed a new shuffled frog-leaping algorithm (SFLA) with memeplex quality (MQSFLA), which was used to minimize total tardiness and makespan simultaneously. Shao et al. [13] proposed a multi-neighborhood IG algorithm so as to solve the problem. Li et al. [14] investigated an improved IG algorithm to solve the DPFSP with both robotic transportation and order constraints. Jiang et al. [15] studied the energy-aware DHFS with multiprocessor tasks with considering total energy consumption and makespan. Niu et al. [16] developed an improved NSGA-II algorithm to solve an energy-efficient distributed assembly blocking flow shop problem. Qin et al. [17] utilized a realistic DHFS where a novel integrated production and distribution scheduling problem is focused.

In realistic industry system, including the glass manufacturing system, the improvement of glass raw materials processing has been studied by many researches [18–20], and therefore, the scheduling efficiency has become increasingly important [21]. Na et al. [22] addressed the glass optimization problems by using heuristic methods. Lozano et al. [23] proposed a two-phase heuristic that combines exact methods and searching heuristics. Wang et al. [24] proposed two heuristics based on decomposition idea to minimize total electricity cost and makespan. Wang et al. [25] formulated a mixed integer programming (MIP) for the problem. Typically, a highly energy-consuming stage (i.e., depreciation of machinery) exits in glass making process, which takes up a large part of the production cost. As a result, considering energy consumption in glass manufacturing system is practical as well as necessary.

Recently, multiobjective optimization algorithms have been applied and considered in many domains [26–31]. Shahvari et al. [32] considered a tabu search (TS) algorithm to minimize two different objectives. Zhang et al. [33] proposed a novel multiobjective multifactorial immune algorithm with a novel information transfer method to deal with multiobjective multitask optimization problems. Wang et al. [34] improved the overall efficiency of optimizing multiple tasks simultaneously by reusing the learned knowledge. Li et al. [35] solved flow shop scheduling problems with a novel multiobjective local search framework-based decomposition. Li et al. [36] developed a knowledge-based adaptive reference points multi-objective algorithm (KMOEA) to solve a DHFS with variable speed constraints. Du et al. [37] proposed a hybrid multi-objective optimization algorithm based on an estimation of distribution algorithm (EDA) and deep Q-network to solve a flexible job shop scheduling problem (FJSP) with time-of-use electricity price constraint. Mou et al. [38] developed an effective hybrid collaborative algorithm for energy-efficient distributed permutation flow-shop inverse scheduling. Li et al. [39] proposed an improved artificial immune system (IAIS) algorithm to solve a special case of the FJSP in flexible manufacturing systems. However, less literature investigated the multi-objective optimization in glass manufacturing systems.

Therefore, to solve DHFS in glass manufacturing systems, we propose an improved hyperplane assisted evolutionary algorithm (IhpaEA). The main contributions of this study are as follows: (1) each solution is represented with a three-dimensional vector, including the factory assignment, machine assignment, and operation scheduling; (2) an efficient initialization strategy is developed to increase the diversity of the population (3) an improved crossover operator is designed to enhance the global search abilities of the proposed algorithm; and (4) a cooperative search method is designed to enhance the local search abilities of the proposed algorithm deeply.

The structure of the rest paper is as follows. The problem descriptions are given in Section 2. Next, the developed IhpaEA framework is presented in Section 3. Then, the detailed components of the imposed algorithm are discussed in Section 4. Section 5 illustrates the experimental results to show the advantages of the algorithm. Finally, the last section shows the conclusion and future research directions.

The DHFS addressed in this study can be described as follows. There are n independent jobs to be assigned to f factories. Each factory consists of a series of

1) Assumptions:

• Each job should be released at time zero and be operated from the first stage to the next stage;

• All machines are available at time zero and remain continuously available over the entire production horizon;

• A job can be processed on exactly one machine at a time, and a machine can process exactly one job at a time;

• At each stage, one job can select one suitable machine from the parallel machine;

• There is unlimited buffer between stages;

• All machines belonging to the same stage have similar processing abilities.

2) Notations and variables:

Indices:

Parameters:

Variables:

S

Completion time of

Makespan, i.e., the maximum completion time.

Machine power of

Machine working time of

Total energy consumption.

Decision Variables:

3) Objective functions:

The makespan (

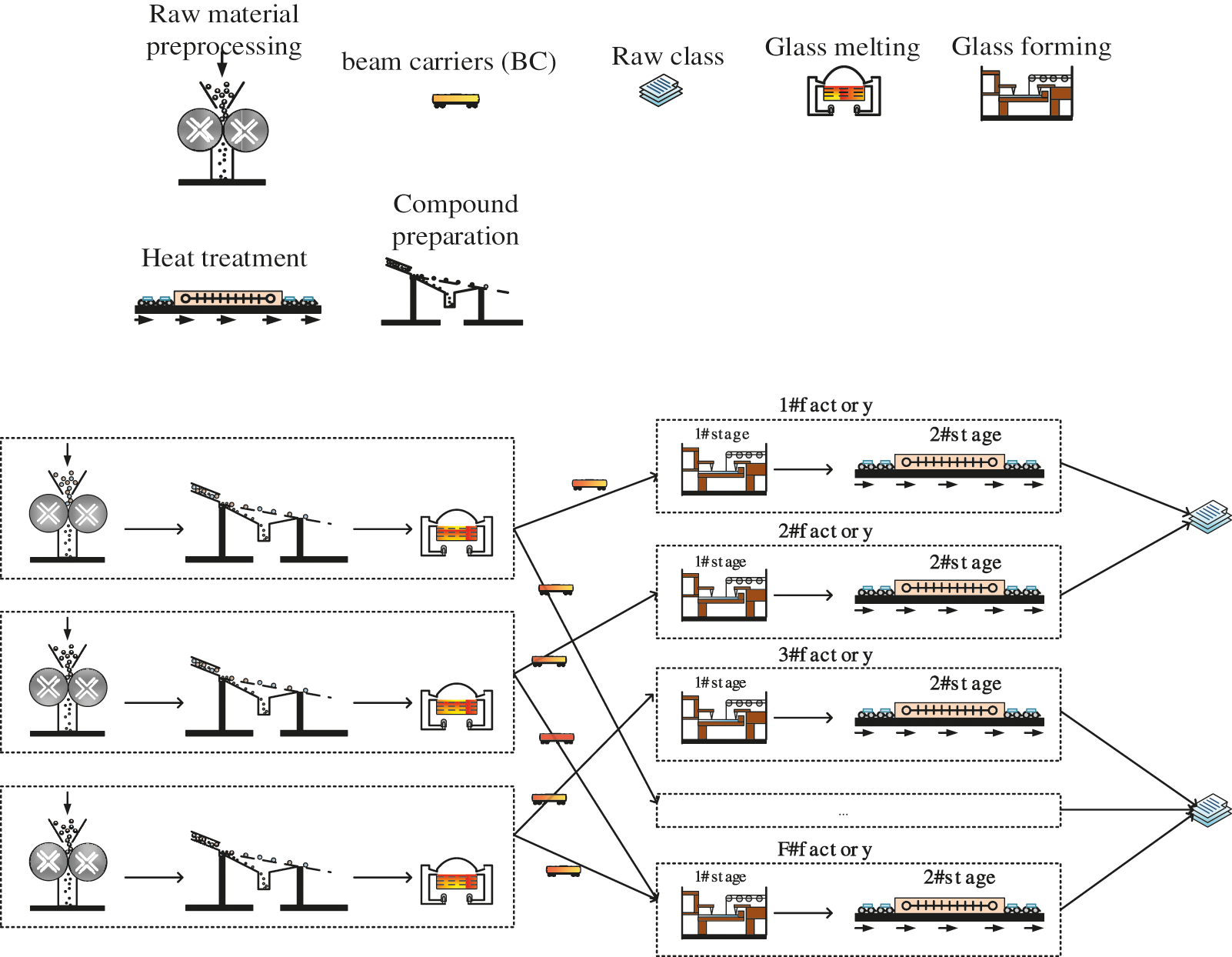

A detailed illustration of the considered realistic DHFS is presented in a glass manufacturing casting system in Fig. 1. A specified quantity of molten glass can be provided by three processing stations. Many beam carriers (BCs) are used to transport those pouring molten glass. Each job or BC is transported to an available factory. The molten glass transported by BC will be operated through at least two stages in each factory: 1) glass forming; and 2) heat treatment stages. The processing operations are the same in all the factories for each BC. After processing in the designated factory, BC will be moved to the next stage, in which one machine will be selected for continuous casting procedure. The specified amount of charging shall be handled for each assigned machine. Fig. 1 presents that the complete working flows in the basic glass manufacturing casting system which can be considered as a typical DHFS with several stages in the last part. Moreover, the realistic processing systems should consider the deteriorating job constraint [33,34].

Figure 1: Realistic DHFS problem in a glass manufacturing system

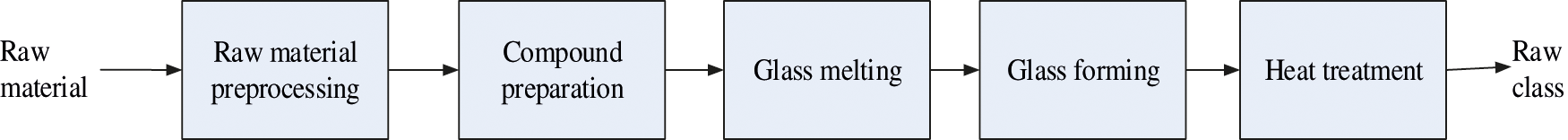

A common production flow is shared by different glass manufacturing systems, i.e., raw glass should experience preprocessing, melting, and forming processes in sequence, as shown in Fig. 2. Specific processing requirements or features are in individual manufacturing systems with the considering that various types of glass are provided by different manufacturers. The detailed processing characteristics of this study are as below:

(1) Raw material preprocessing: Crush large raw materials (soda, quartz sand, feldspar, limestone, etc.) to dry raw materials which are wet, and then remove iron from raw materials to ensure glass quality.

(2) Compound preparation.

(3) Glass melting: In order to make the glass raw materials meet the forming requirements of uniform, bubble free and molten liquid glass, the glass raw materials need to be placed in the pool kiln or crucible kiln and heated at high temperature (1500–1600 degrees).

(4) Glass forming: Liquid glass is processed into the required shape of the specific products.

(5) Heat treatment: Through annealing, quenching and other processes to change the structural state of glass.

Figure 2: General procedure of a raw glass manufacturing system

In this section, the proposed IhpaEA algorithm is presented to solve the considered DHFS problem. The first part describes the main framework of the proposed IhpaEA. Then the encoding, decoding, initialization, crossover, and other problem-specific heuristics are presented, respectively.

3.1 Framework of the Proposed IhpaEA

The main framework of the proposed IhpaEA algorithm is an enhanced inverted GA (genetic algorithm) indicator based hpaEA [40]. In IhpaEA, the main components, including the uniform reference point, mating selection and the environmental selection functions are directly included from hpaEA. The prominent solutions are retained by the environment selection strategy of hyperplane assisted evolutionary algorithm. Besides, it uses two criteria to select the size of population and the non-dominated solutions.

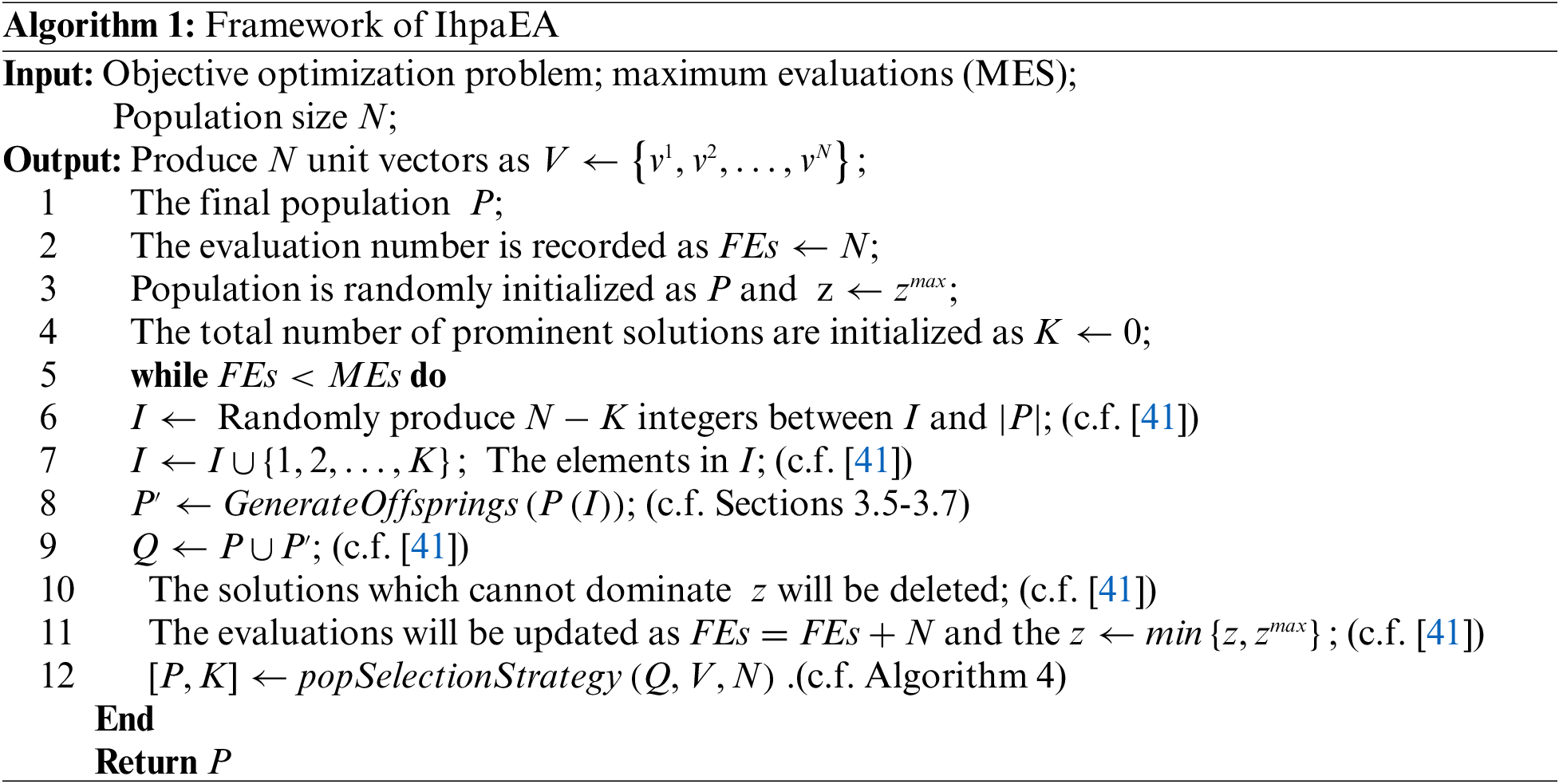

Algorithm 1 represents the framework of IhpaEA, where the first step is to initialize four parameters (1) an initial population P (line 1); (2) vectors V (line 2); (3) the number of prominent solutions (line 3) and (4) the evaluation functions (line 4); and the loop of IhpaEA (lines 5–12). Each generation performs three steps in the algorithm: (1) mating selection; (2) offspring population generation, and (3) environmental selection. The mating selection tries to assign more evolutionary results to the prominent solutions, and select better solutions. The set

3.2 Representation and Encoding

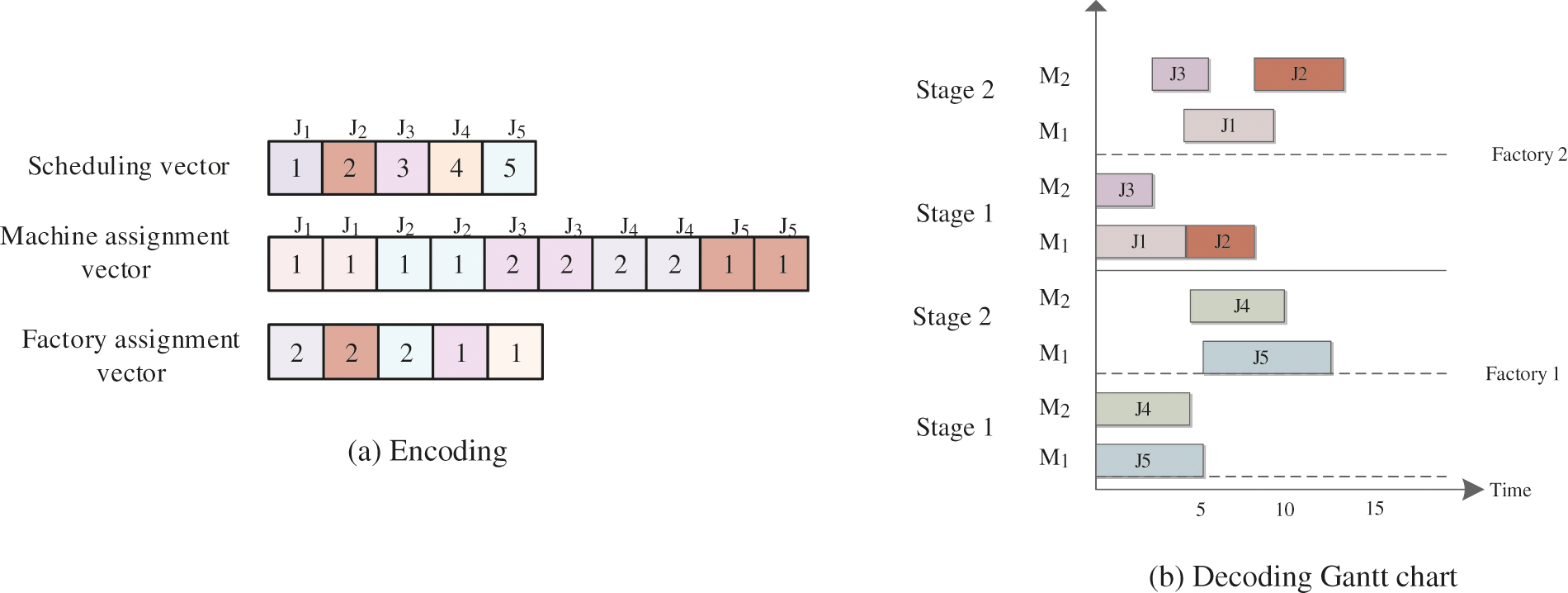

Each solution is represented by a three-dimensional vector as follows.

The first dimensional vector is called scheduling vector, and the length of it equals to the total number of operations

The name of the second dimensional vector is called the machine assignment vector

The third dimensional vector is named as the factory assignment vector, and the length of factory assignment vector equals to the total number of jobs

Fig. 3a gives a solution representation example, where there are five jobs. The total number of stages for each job is 2. The factory assignment vector tells the factory number for each job, the routing vector reports the machine number. Then, the scheduling vector represents the scheduling sequence for each job.

Figure 3: Solution representation

Fig. 3b shows the Gantt chart. The detailed decoding introduces are described as follows:

Step 1: The assigned jobs are scheduled based on the sequence in the scheduling vector which is the first stage of each factory.

Step 2: After determining the factory, each job should select a suitable machine following the earliest available time rule.

Step 3: For the other stages, each job is scheduled as soon as possible after completing its previous operations. The first available suitable machine is also selected.

To solve the considered problem, a solution is encoded with two dispatching rules. The longest processing time at the first stage (LPTF) rule, and the shortest processing time at the first stage (SPTF) rule. Based on the non-increasing total processing times, LPTF generates a permutation. Meanwhile, based on the non-decreasing total processing times, SPTF produces a permutation by sorting the jobs.

To produce an effect initial population, the following technique is used. Suppose the population size is N, the detailed steps are given as follows:

(1) The first

(2) One individual is generated by LPTF. First, all the jobs’ processing time are calculated in each stage. Then, every job in every stage has a processing time and the summation of these time is called total processing time. Finally, the individual is generated by permuting the total processing time in non-increasing order.

(3) SPTF generates the last individual. The first two steps are the same with LPTF. However, the third step is to permute the processing time in a non-decreasing order.

Based on the encoding representation, we proposed a novel crossover heuristic including two parts.

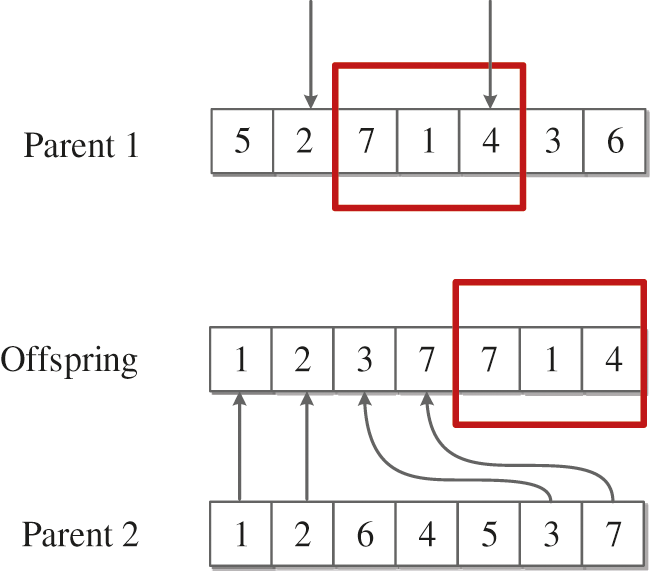

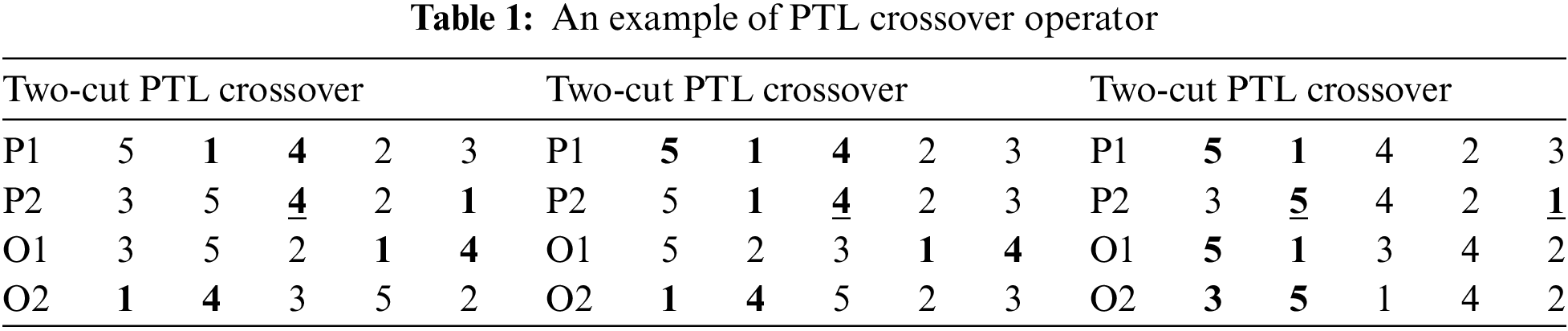

(1) PTL crossover

The first type of crossover is PTL, which can be described as follows:

Step 1: Randomly select two different elements from the first parent.

Step 2: Copy the block of jobs which are cut by the two points from the first parent. And then move the block to the rightmost or leftmost part of the offspring.

Step 3: Place the empty elements of jobs which are remaining from the second parent.

The process of PTL for generating offspring is depicted in Fig. 4. Table 1 provided an example which can figure out the way element are updated.

Figure 4: PTL crossover operator

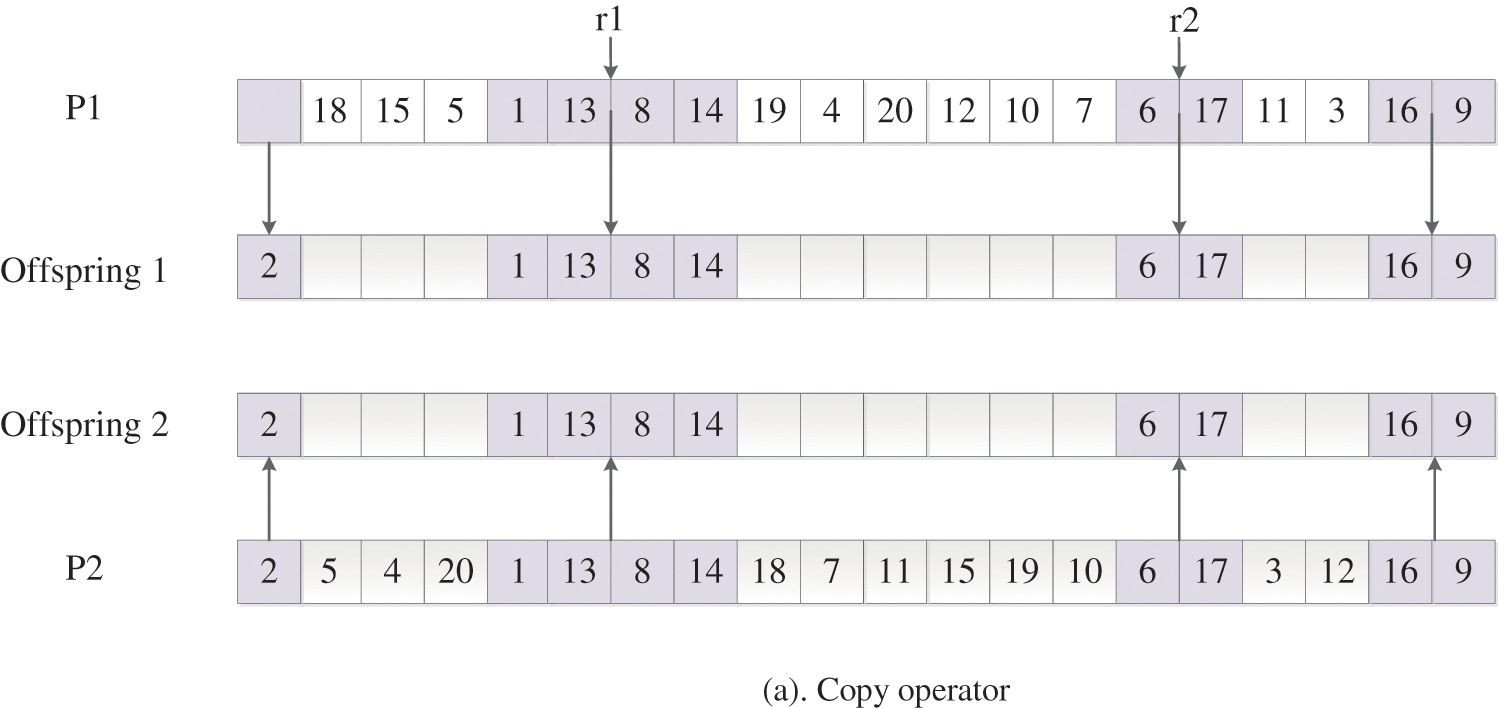

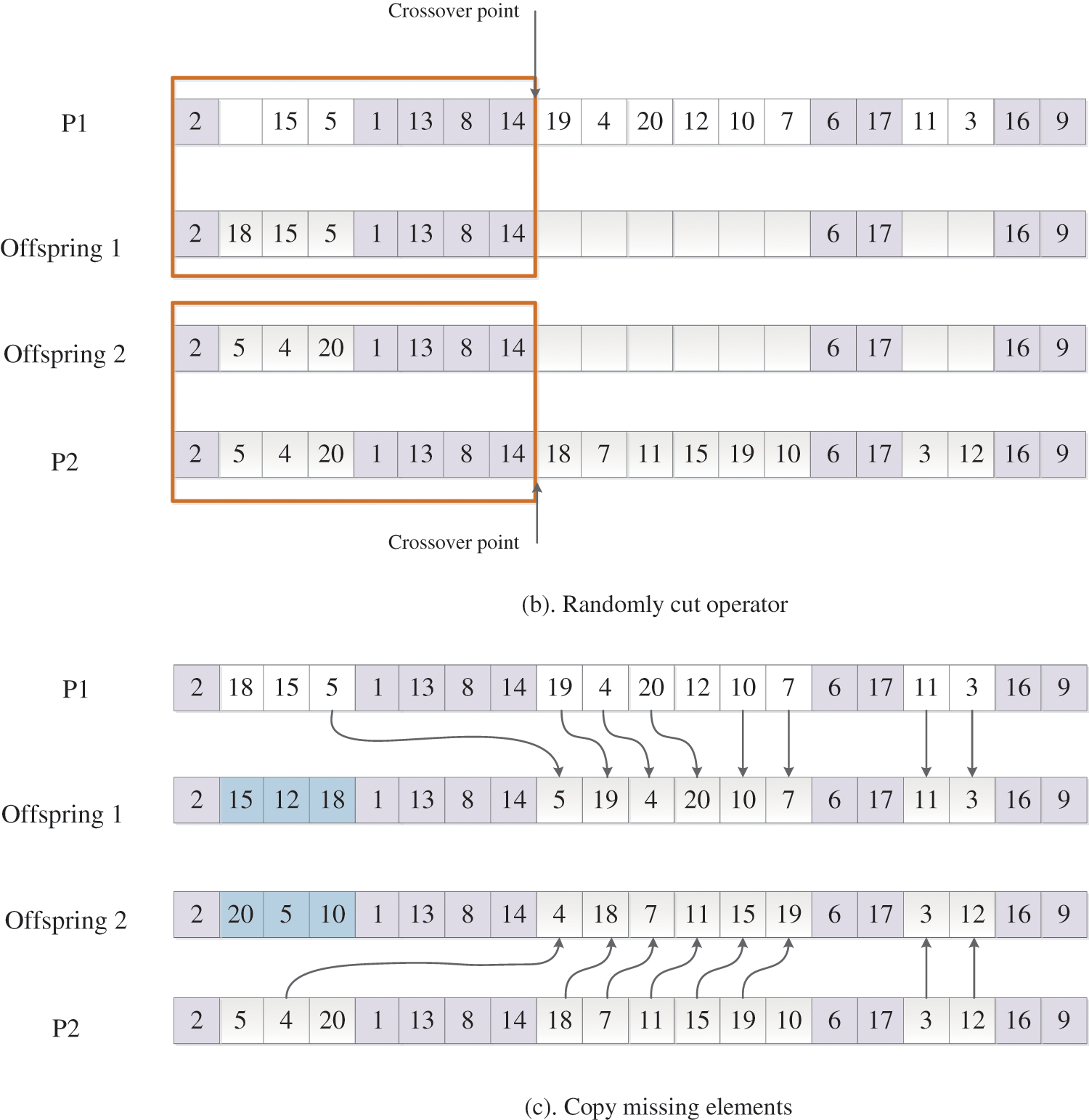

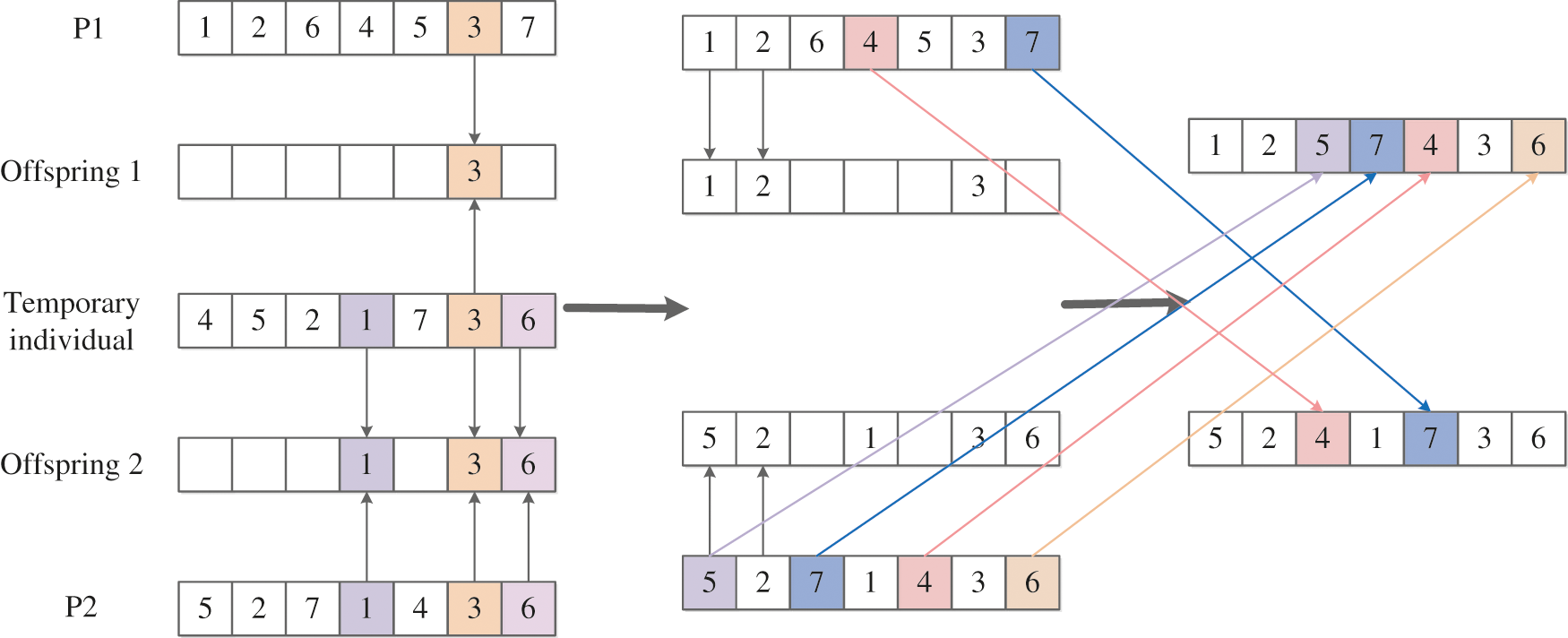

(2) ISJOXI crossover

The second type of crossover operator is Improve Similar Job Order Crossover I or ISJOXI, with which the building blocks of jobs are directly copied to the offspring. In Fig. 5a, a point is randomly selected and the elements before this cut point is copied to the offspring directly, shown in Fig. 5b. Furthermore, in order to maintain feasibility of the job sequence, the ISJOXI crossover operator copies the missing elements of each offspring which are in the relative order of the other parents, shown in Fig. 5c. Lastly, other elements which are not assigned are obtained by performing single point crossover operator on

Figure 5: Process of performing ISJOXI

Figure 6: ISJOXI

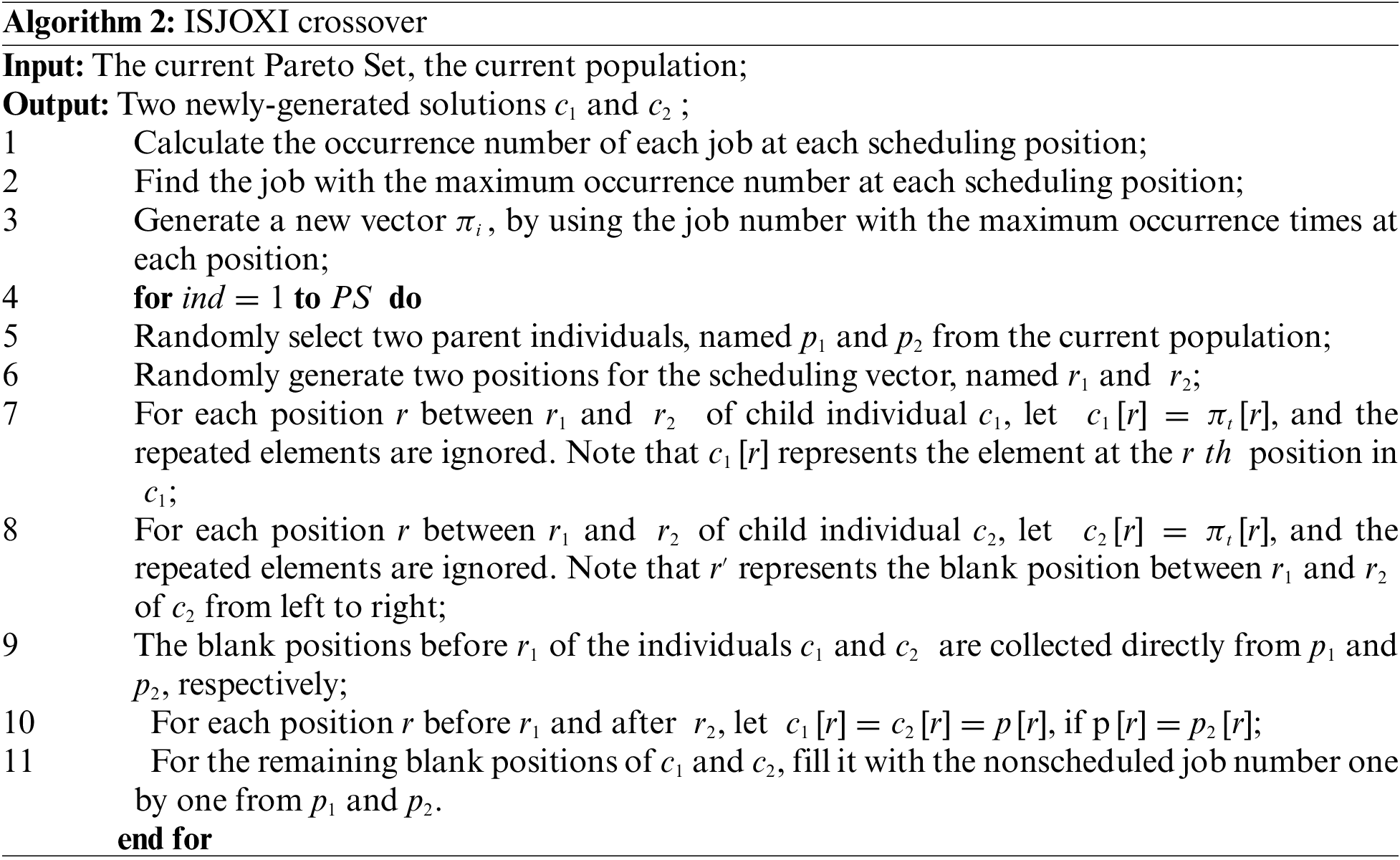

The main steps of ISJOXI crossover are described in Algorithm 2.

Suppose

(1) Mutation for the factory assignment

(2) Mutation for the scheduling vector

(3) Mutation for the machine vector

The procedure of the mutation operator is as follows. Firstly, a position

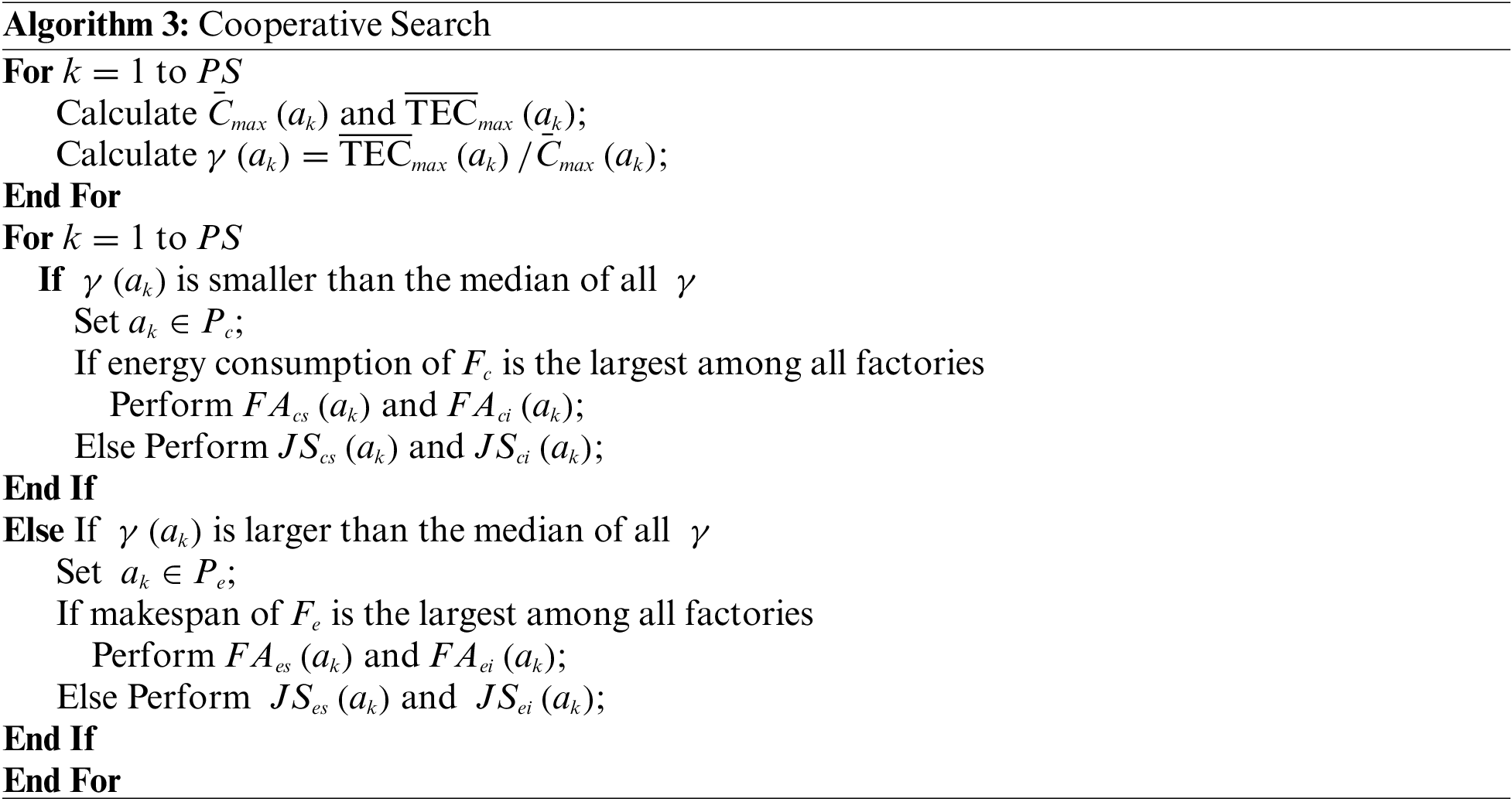

The following multi-objective cooperation local search operator is embedded to achieve good diversity and convergence.

First, in each generation, the maximum completion time of solution a is denoted as

Second, the value

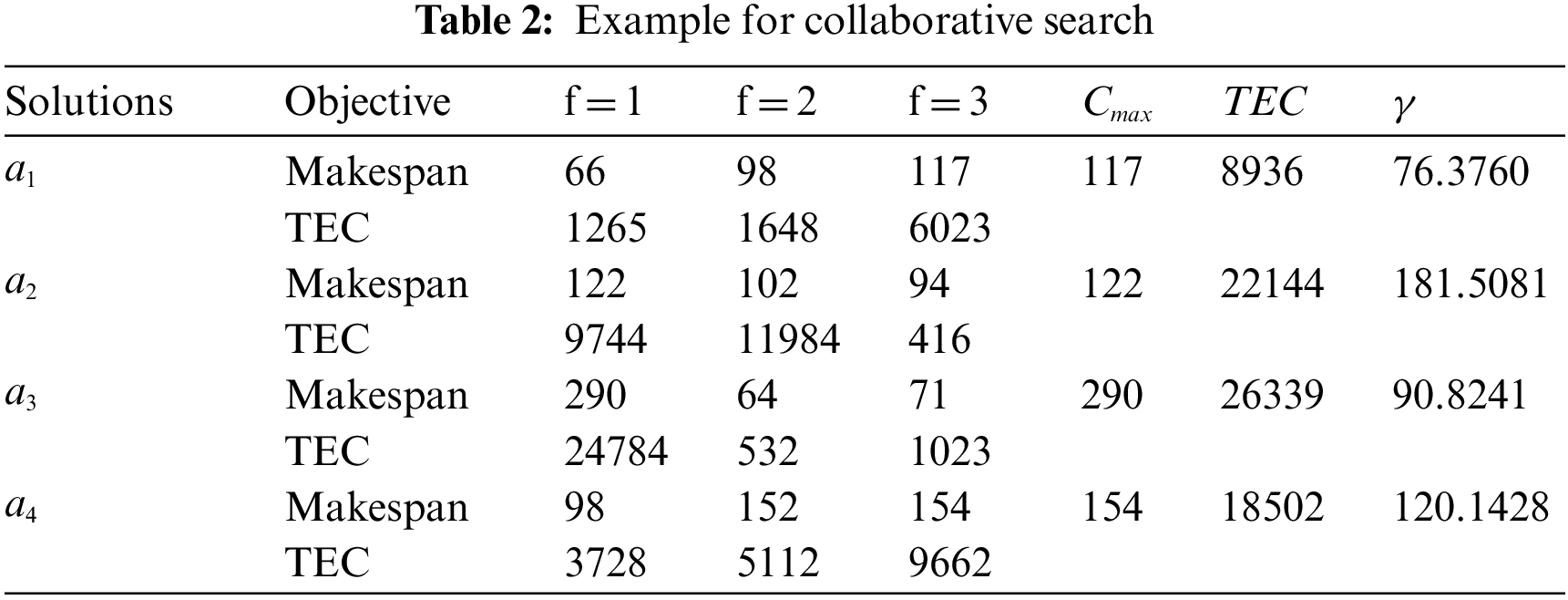

An example is provided in Table 2, where the objective values of a population with four solutions are listed, including the

The computational experiments to test the performance of IhpaEA algorithm is discussed in this section. The improved algorithm was implemented in the PlatEMO v3.0 on an Intel Core i7 3.4-GHz PC with 16 GB of memory. To test the performance of IhpaEA algorithm, 20 different scales of instances are generated according to the realistic flow shop.

All the compared algorithms are used to solving the considered problem, including the encoding, and decoding method, and the initialization procedure. The parameters are set according to their literatures. For each instance, the stop condition is set to 3000 iterations.

30 independent runs are used to test the performance of the proposed algorithm, the results of non-dominated solutions found by all the compared algorithms were collected for performance comparisons. The relative percentage increase (RPI) is used for the ANOVA comparison, which is formulated as follows:

where

20 large-scale test instances of DHFS problem are randomly generated to solve the DHFS problem and test the validity of the hpaEA algorithm based on the actual production data. For example, instance 1 can be denoted with 20 jobs, 2 stages, as well as 3 parallel machines in the first stages as well as 5 parallel machines in the second stages wherein the index of jobs are {20, 30, 50, 80, 100}, the parameter of machines are {2, 3, 4, 5}, the parameter of stages are {2, 3, 5, 10}, and the parameter of factories are {2, 3, 4, 5, 6}, respectively. The four algorithms ran 30 times.

4.2 Efficiency of the Initialization Heuristic

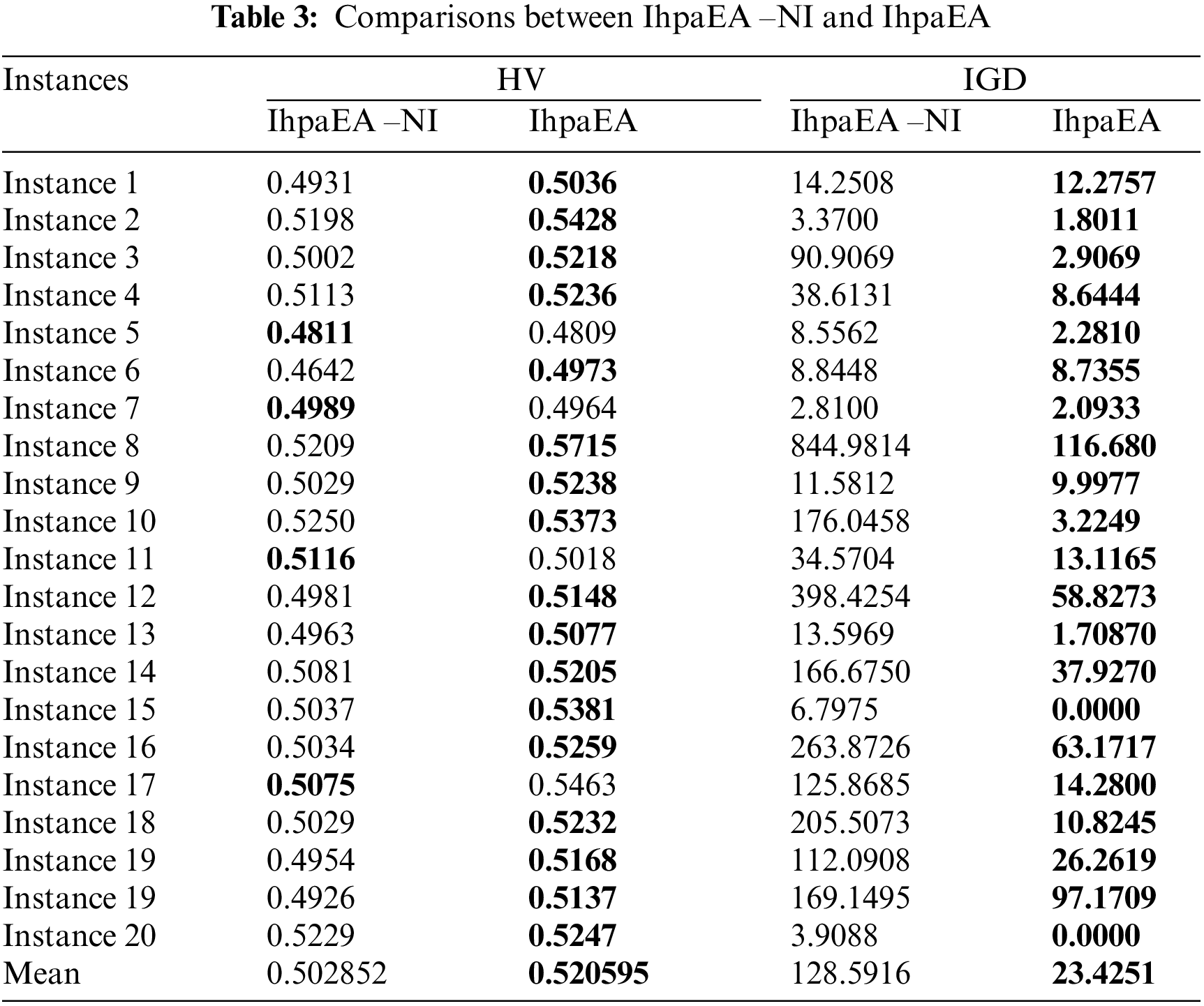

Two types of IhpaEA algorithms are coded to test the initialization heuristic discussed in Section 3.4: a random initialization heuristic named IhpaEA -NI, and IhpaEA with all components. All other components of the two comparison algorithms are the same.

Table 3 reports the comparison results between IhpaEA -NI and IhpaEA. Instance numbers are given in the first column, the HV results collected from the two compared algorithms are listed in the following two columns, respectively. The last two columns illustrate the IGD values by IhpaEA -NI and IhpaEA, respectively.

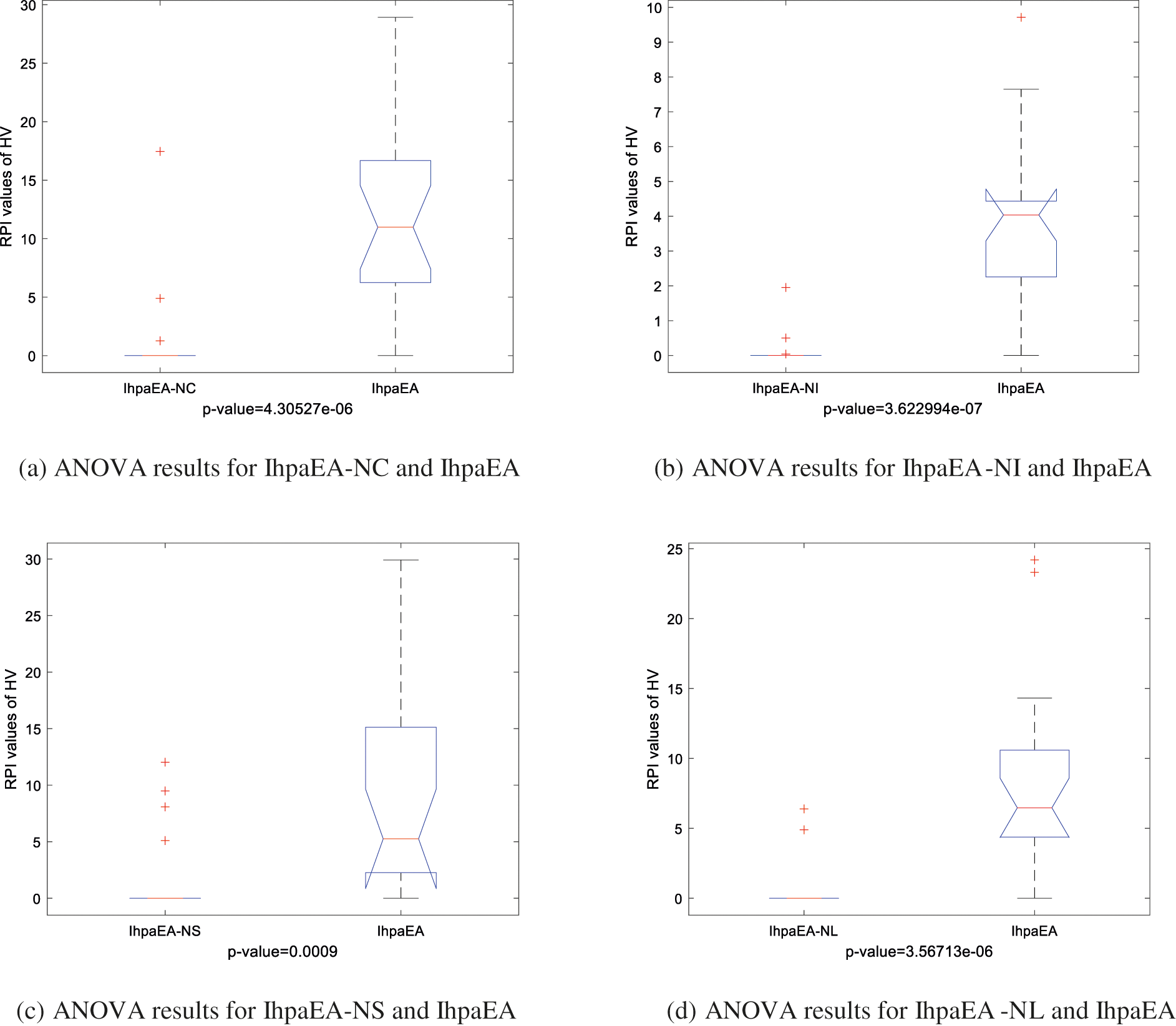

It can be concluded from the comparison results that: (1) IhpaEA algorithm obtains 16 better results by considering the HV values of the IhpaEA-NI algorithm, and the slightly worse results for the other two instances; (2) for the IGD values, IhpaEA obtains 20 better results out of the given 20 different scale instances; and (3) from the average performance in HV and IGD given in the last line and the ANOVA results from Fig. 7a, it can be seen that IhpaEA is significantly better than the IhpaEA -NI algorithm, which verify the efficiency of the proposed initialization heuristic.

4.3 Efficiency of the Crossover Operator

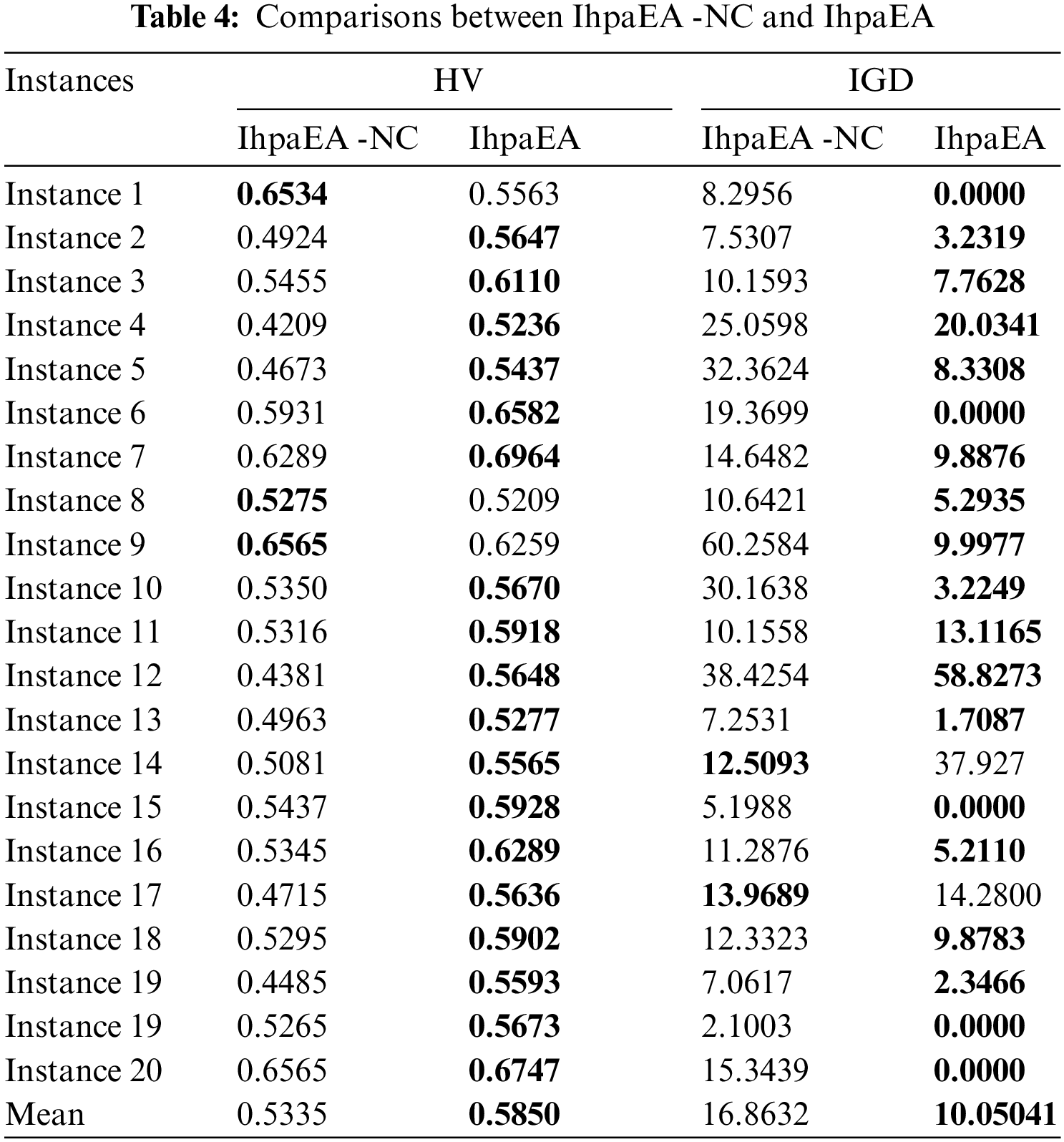

In order to test the performance of the crossover operators discussed in Section 3.5, two different types of IhpaEA algorithms are coded, i.e., the IhpaEA-NC algorithm with the classical two-point crossover, and the IhpaEA algorithm with all the two crossover operators.

Figure 7: Means and 95% LSD interval for pairs of compared algorithms

From the comparison results given in Table 4, it can be observed that: (1) Compared with the IhpaEA -NC, IhpaEA algorithm obtains 17 better results based on the HV values; (2) the ANOVA results from Fig. 7b shows that the IhpaEA obtains significant better results based on the HV results, where the p-value equals to 4.30527e-06 (3) for the IGD values, IhpaEA obtains 18 better results; and (4) from the average performance in HV and IGD given in the last line, the efficiency of the proposed crossover heuristic can be verified.

4.4 Efficiency of the Mutation Operator

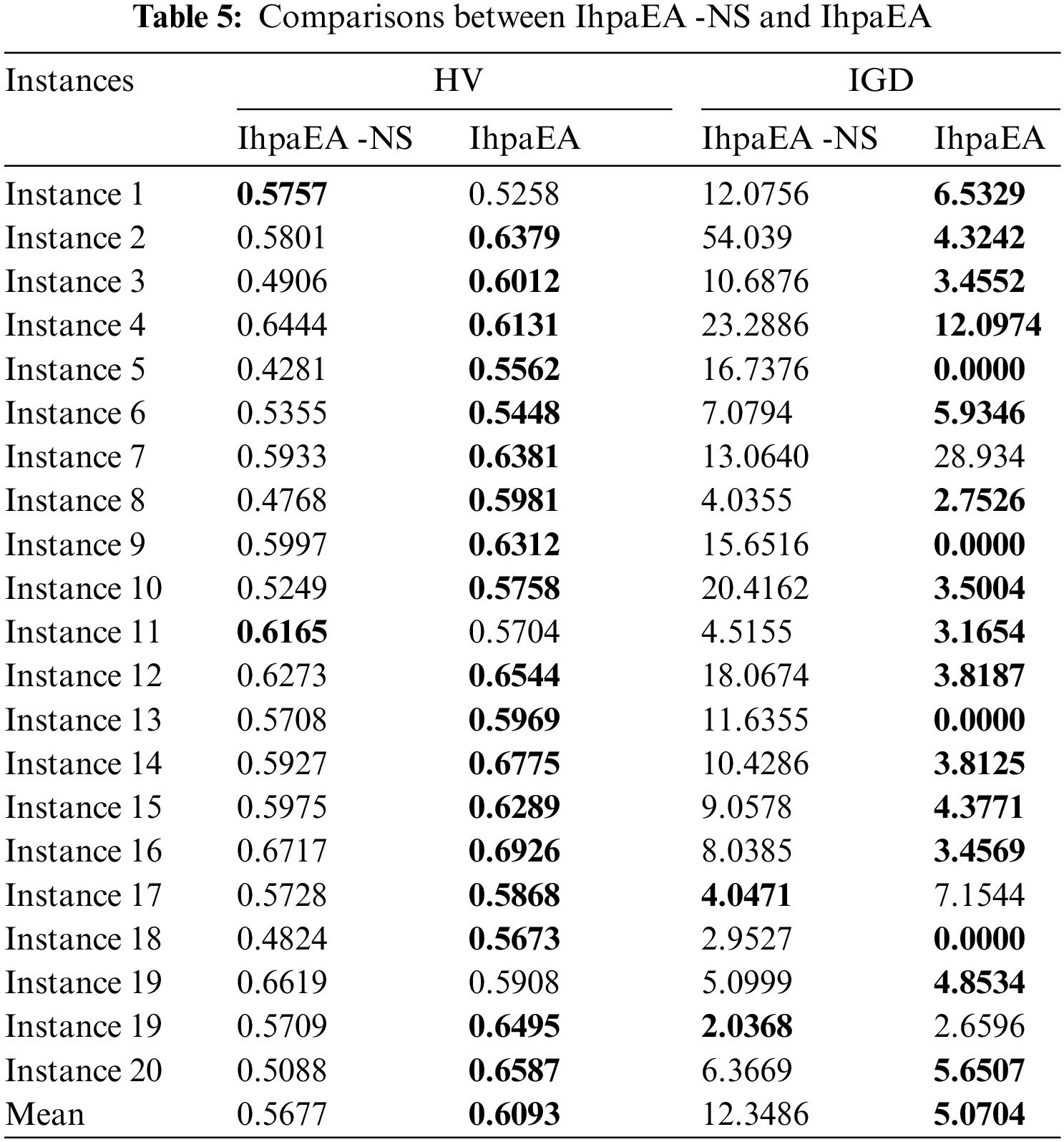

Two different types of IhpaEA algorithms are coded to test the performance of the mutation operator discussed in Section 3.6, i.e., the proposed IhpaEA-NS algorithm without mutation operator, and the IhpaEA algorithm with all the components.

From the comparison results given in Table 5, it can be concluded that: (1) compared with the IhpaEA-NS algorithm, IhpaEA obtains 18 better results, based on the HV values; (2) the ANOVA results from Fig. 7c shows that the IhpaEA obtains significant better results based on the HV results, where the p-value equals to 0.0009; (3) for the IGD values, IhpaEA obtains 18 better results; and (4) from the average performance in HV and IGD given in the last line, the efficiency of the proposed mutation operator can be verified.

4.5 Efficiency of the Local Search Operator

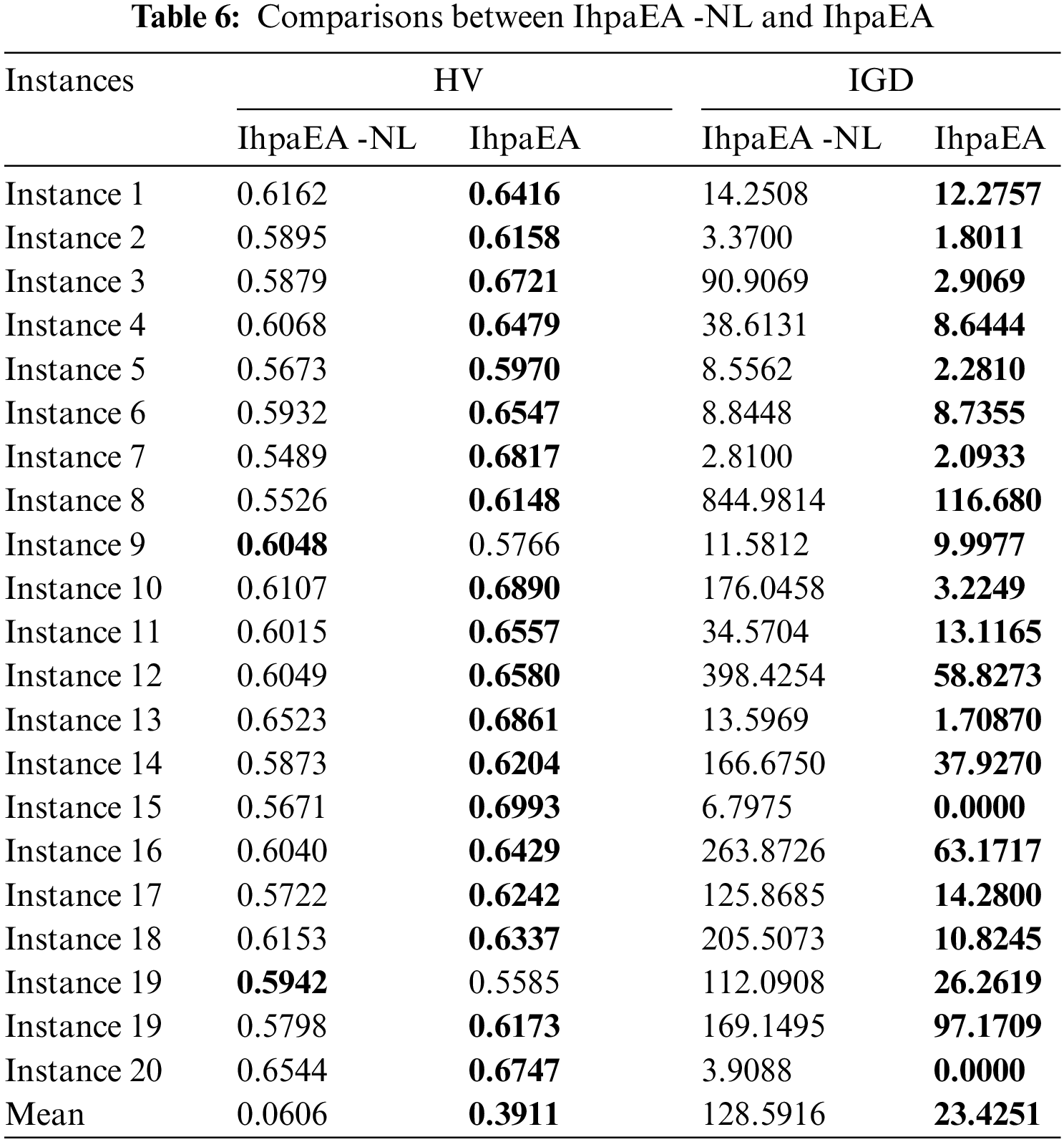

To evaluate the performance of the local search heuristic discussed in Section 3.7, two types of IphaEA algorithms are coded: IhpaEA-NL without the local search heuristic and IhpaEA with all components that mentioned in Section 3.7.

From the comparison results given in Table 6, it can be observed that: (1) considering the HV values, compared with the IhpaEA -NL algorithm, IhpaEA obtains 18 better results; (2) the ANOVA results from Fig. 7d shows that the IhpaEA obtains significant better results considering the HV results, where the p-value equals to 3.56712e-06 (3) for the IGD values, IhpaEA obtains 20 better results; and (4) from the average performance in HV and IGD given in the last line, the efficiency of the proposed heuristic can be verified.

4.6 Comparisons of the Efficient Algorithms

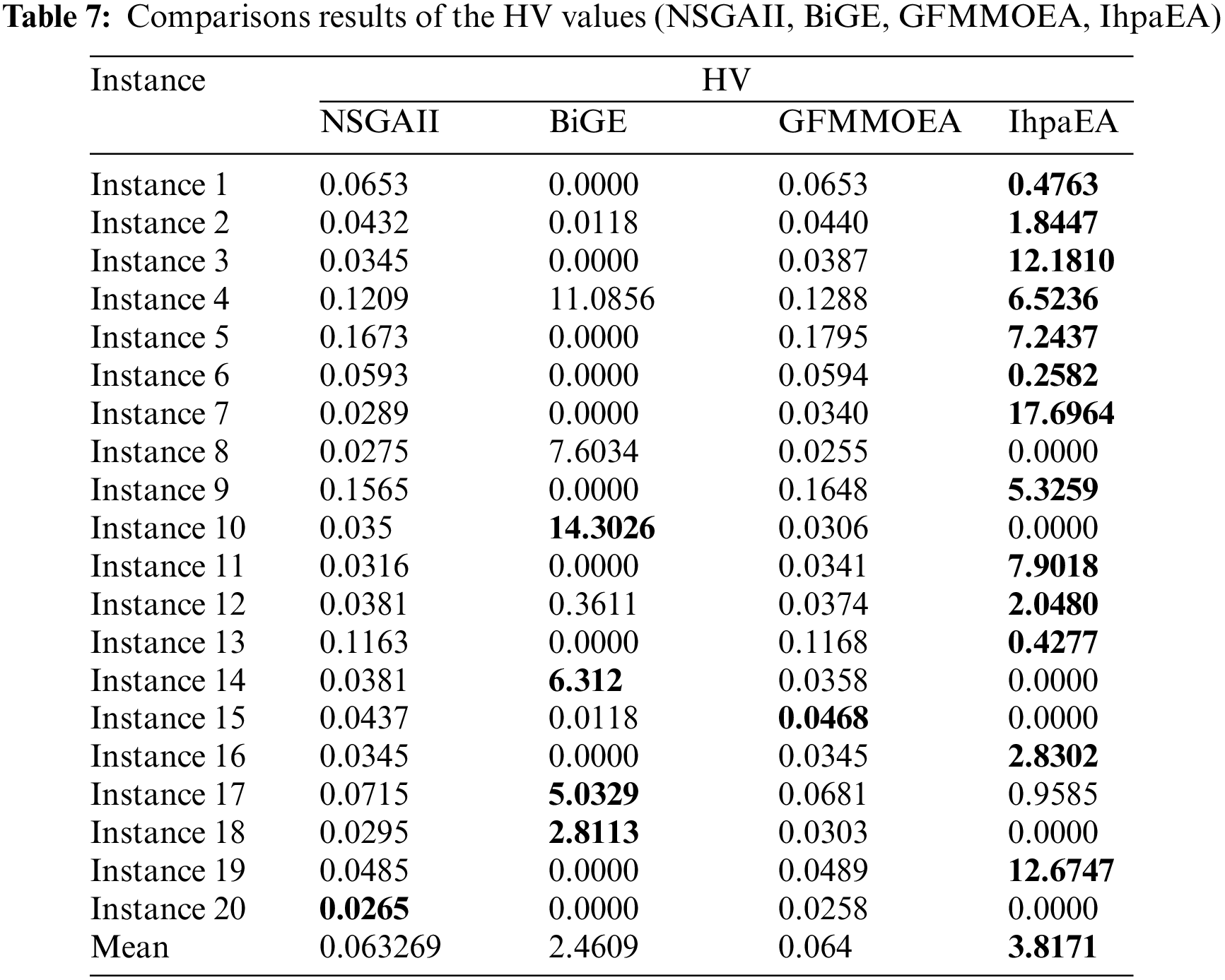

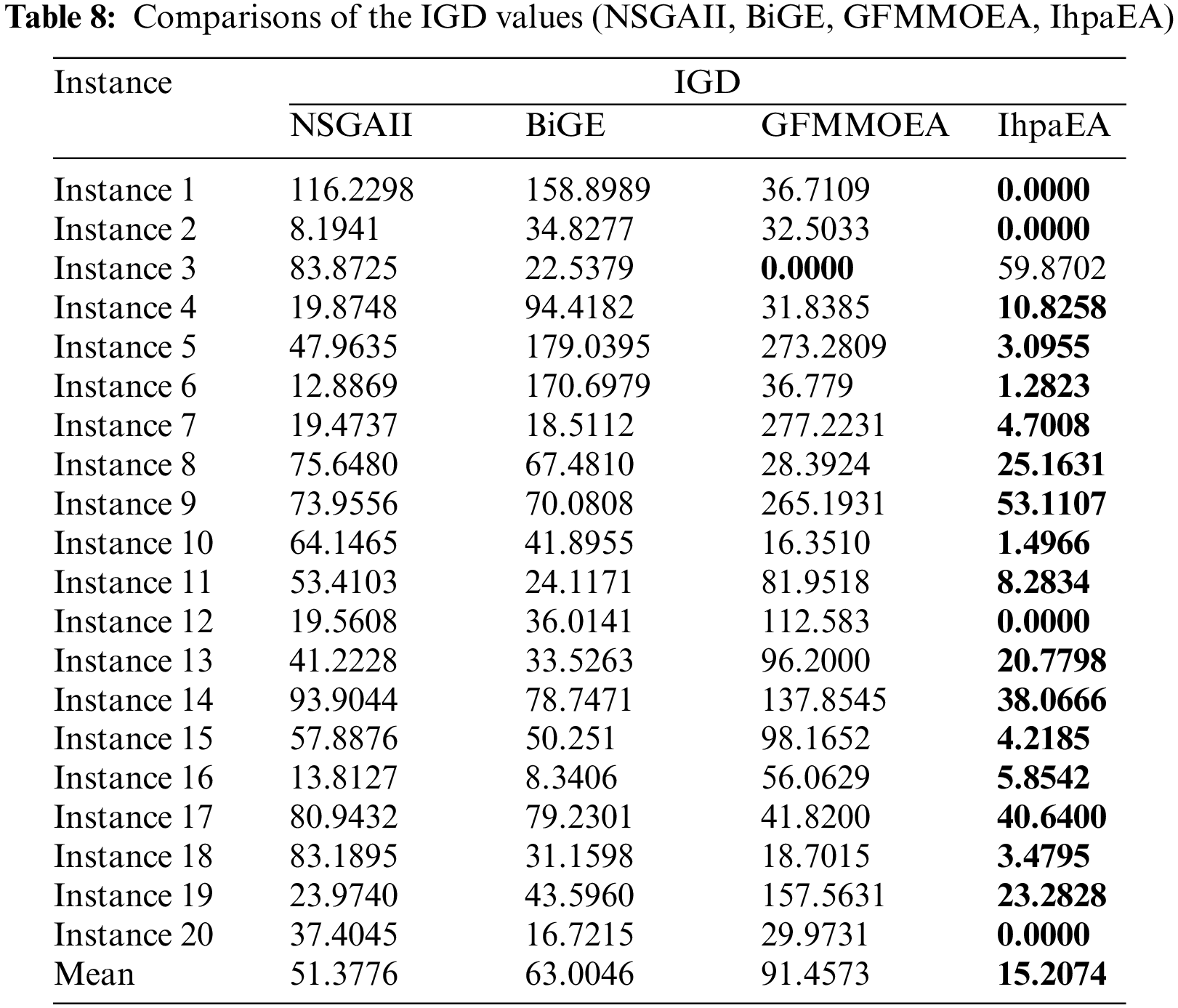

Three algorithms are selected, namely, NSGAII [37], GFMOEA [38], BiGE [39], to test the effectiveness of the IhpaEA algorithm. Table 7 presents the HV and IGD results after 30 independent runs.

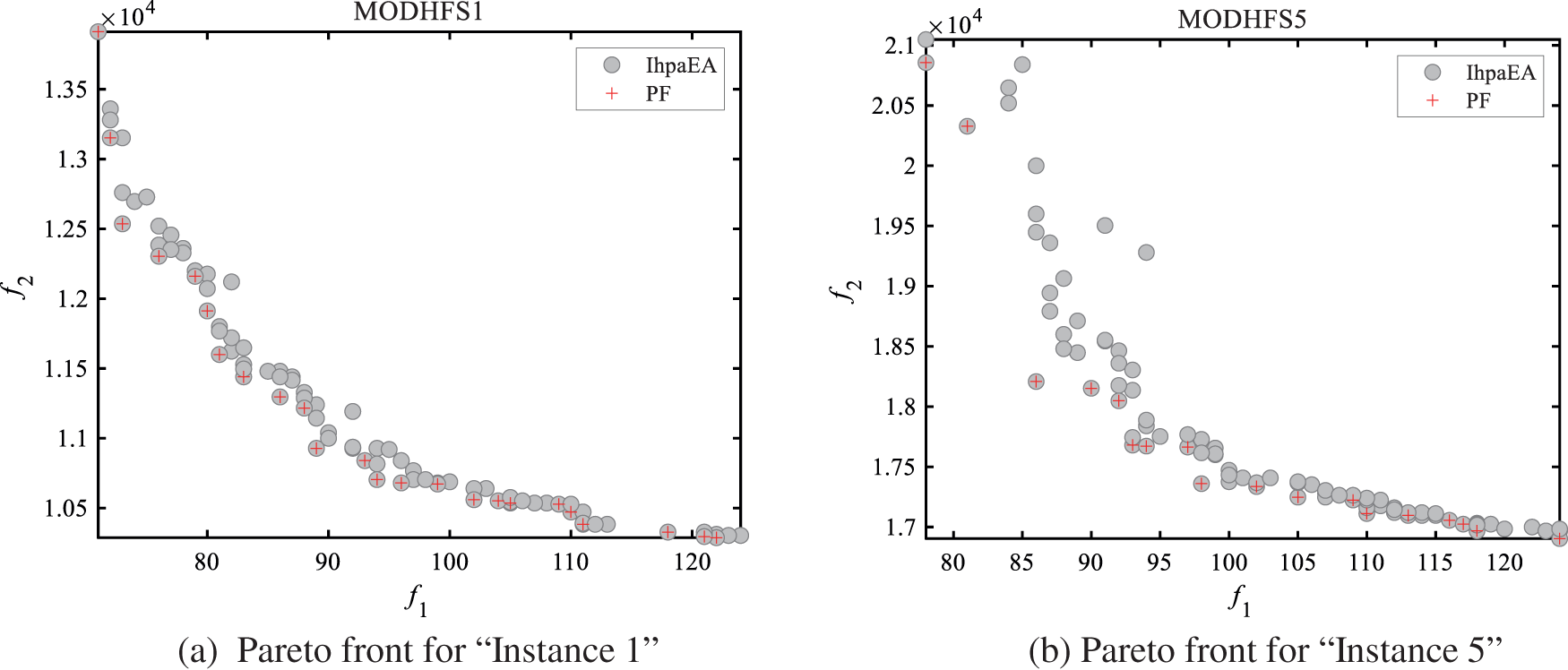

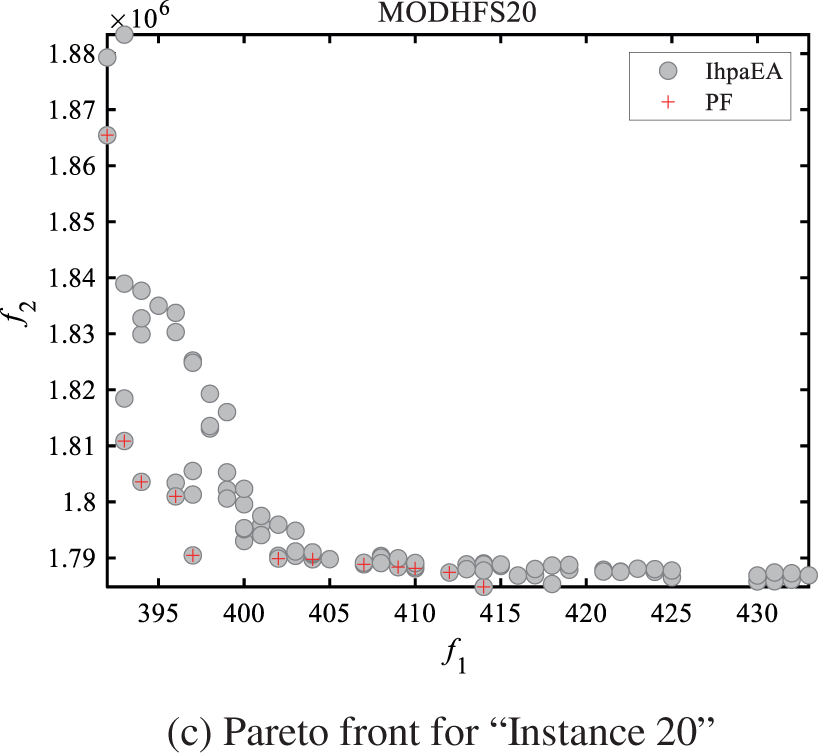

Figs. 8a–8c shows the Pareto front charts for solving three different problem scale instances, i.e., “Instance 1”, “Instance 5”, and “Instance 20”. It can be observed from Fig. 8 that, the solutions obtained by the IhpaEA algorithm are close to the Pareto front and well-distributed.

Figure 8: Pareto front results

Table 7 reports the comparison results of the HV values for the given 20 different scale instances. The first column represents the number of the instances. Then, the results collected by NSGAII, GFMMOEA, BiGE, and IhpaEA, are illustrated in the following four columns, respectively. Table 8 reveals that: (1) 13 better values obtained by the proposed IhpaEA algorithm for the given 20 instances perform significantly better than other 3 comparison algorithms; and (2) the average values of the last line further evaluate the efficiency of the IhpaEA. In addition, from the compared results of the IGD values reported in Table 8, it can be known that the proposed IhpaEA algorithm gets 19 better values, which further test the superiority of the IhpaEA algorithm.

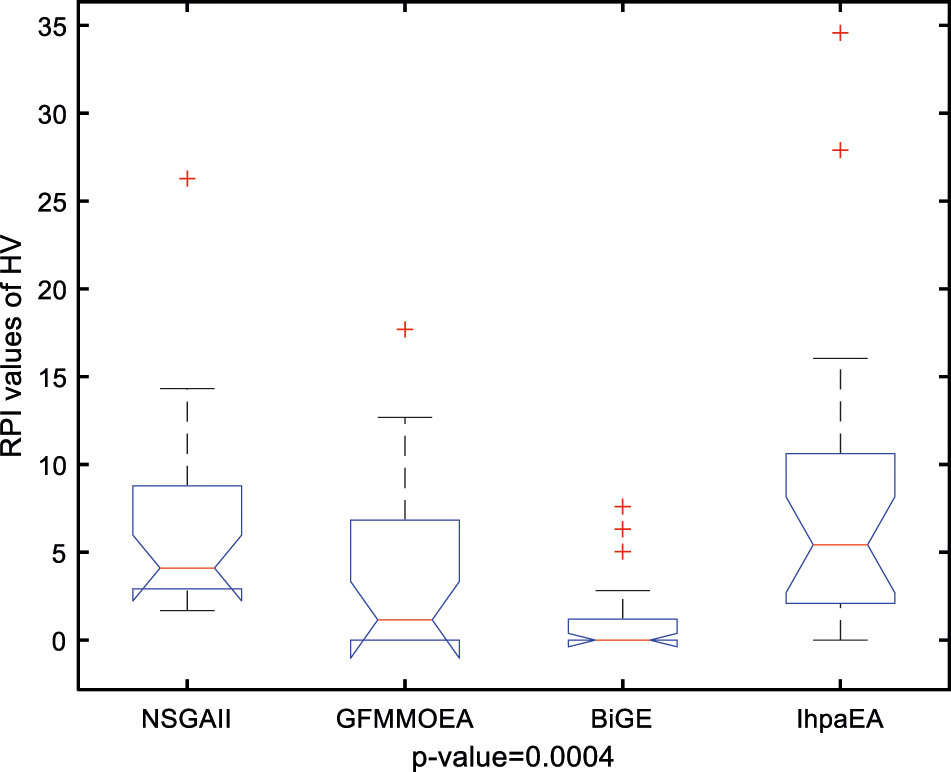

A multifactor analysis of variance (ANOVA) is also performed to verify the difference from the above tables, based on three compared algorithms namely, NSGAII, GFMMOEA and BiGE. Fig. 9 reveals the means and the 95% LSD (Fisher's Least Significant Difference) intervals for the best values of the three compared algorithms. The result of the three comparison algorithms shows statistically significant difference. From Fig. 9 we can conclude that the IhpaEA algorithm performs better than other three compared algorithms obviously.

Figure 9: Multi-compare results for NSGAII, GFMMOEA, BiGE, and IhpaEA

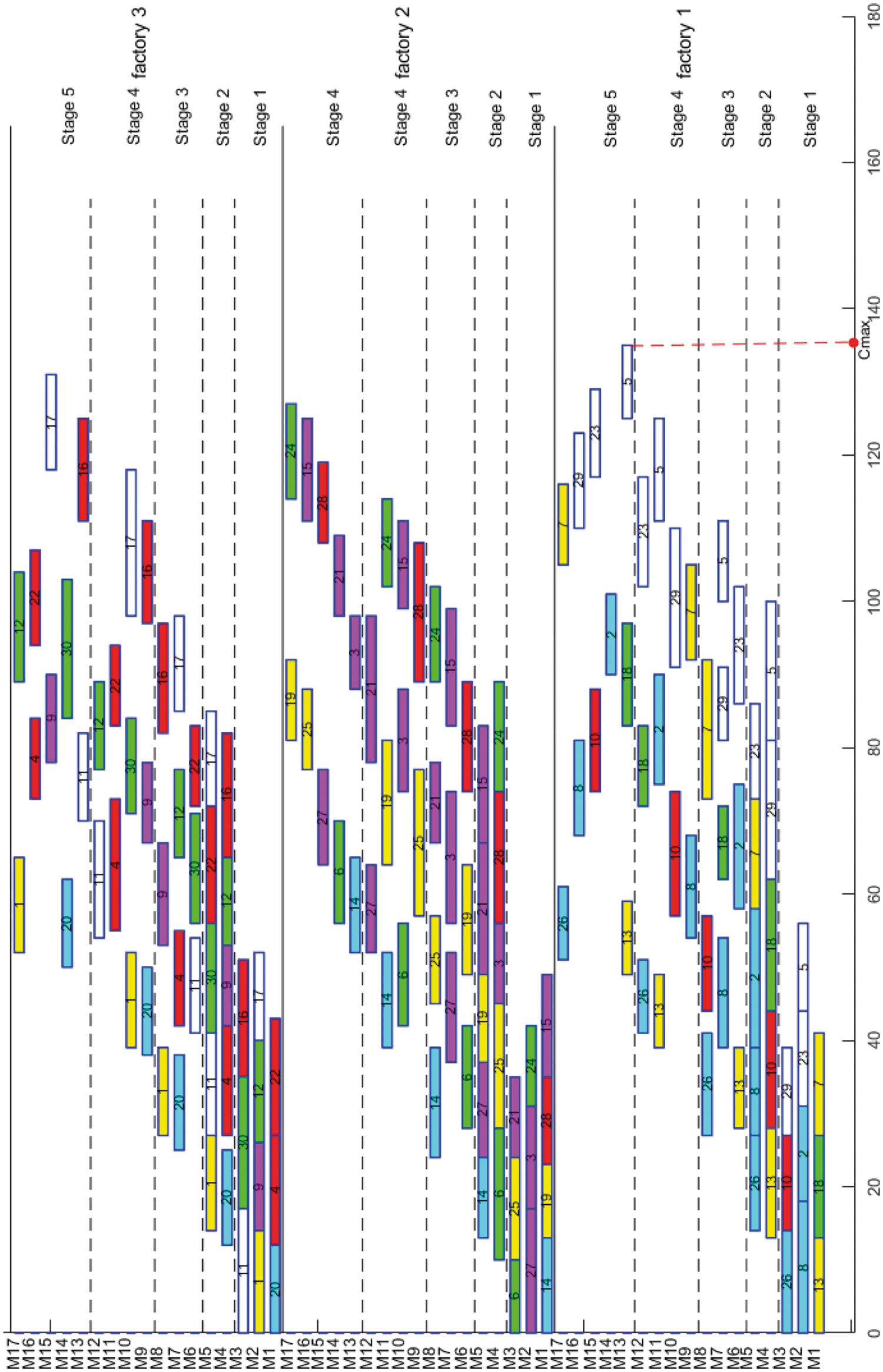

Fig. 10 shows the Gantt chart for one of the optimal solutions for “Instance 7”. It can be concluded from Fig. 10 that the proposed algorithm can obtain some feasible and efficient solutions for the considered problem.

Figure 10: Gantt charts for instance 7

From the above discussed comparison results, the efficient performance of the proposed IhpaEA algorithm has been tested. The main advantages of IhpaEA are as follows: (1) the proposed initialization heuristic, which can enhance the population diversity and quality; (2) the Pareto-based crossover operator enhance the global search abilities; (3) the mutation operator enhance the convergence of optimization process; and (4) a cooperation of search operators improve the local search abilities.

This paper studies a DHFS problem with makespan and total energy consumption. To solving the problem, a multiobjective optimization algorithm is proposed. The contributions are as follows: (1) an efficient encoding and decoding mechanism is embedded; (2) in the initialization phase of the algorithm, considering the constraints in the model, two heuristics are developed; (3) a Pareto-based crossover operator is designed; and (4) a cooperation of search operator is developed to further improve the quality of the solution and accelerate the convergence speed of the algorithm. To further illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, IhpaEA is compared with three other multi-objective algorithms, including NSGA-II, BiGE, and GFMMOEA, The Pareto frontier is closer to the optimal solution than the other three algorithms.

We test the IhpaEA algorithm with different scales and compare several efficient algorithms with the IhpaEA algorithm. The robustness as well as efficiency is shown by experimental results. There are some works need to be focused as follows: (1) to improve the search capabilities, more local optimization methods or other efficient heuristics need to be introduced; (2) some useful dynamic and rescheduling strategies should be considered in flow shop scheduling problem; (3) more conflict objectives such as maximum workload and parallel batch workload need to be focused on.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ruiz, R., Vázquez-Rodríguez, J. A. (2010). The hybrid flow shop scheduling problem. European Journal of Operational Research, 205(1), 1–18. DOI 10.1016/j.ejor.2009.09.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu, M., Yang, X., Chu, F., Zhang, J., Chu, C. (2020). Energy-oriented bi-objective optimization for the tempered glass scheduling. Omega, 90, 101995. DOI 10.1016/j.omega.2018.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chung, T. P., Sun, H., Liao, C. J. (2017). Two new approaches for a two-stage hybrid flowshop problem with a single batch processing machine under waiting time constraint. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 113, 859–870. DOI 10.1016/j.cie.2016.11.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pan, Q. K., Gao, L., Wang, L. (2019). A Multi-objective hot-rolling scheduling problem in the compact strip production. Applied Mathematical Modelling, 73, 327–348. DOI 10.1016/j.apm.2019.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xu, Y., Wang, L., Wang, S., Liu, M. (2014). An effective hybrid immune algorithm for solving the distributed permutation flow-shop scheduling problem. Engineering Optimization, 46(9), 1269–1283. DOI 10.1080/0305215X.2013.827673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bargaoui, H., Driss, O. B., Ghédira, K. (2017). A novel chemical reaction optimization for the distributed permutation flowshop scheduling problem with makespan criterion. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 111, 239–250. DOI 10.1016/j.cie.2017.07.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Pan, Q. K., Gao, L., Wang, L. (2021). An effective cooperative co-evolutionary algorithm for distributed flowshop group scheduling problems. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, 52(7), 5999–6012. DOI 10.1109/tcyb.2020.3041494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Huang, J. P., Pan, Q. K., Miao, Z. H., Gao, L. (2021). Effective constructive heuristics and discrete bee colony optimization for distributed flowshop with setup times. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 97, 104016. DOI 10.1016/j.engappai.2020.104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Meng, T., Pan, Q. K. (2021). A distributed heterogeneous permutation flowshop scheduling problem with lot-streaming and carryover sequence-dependent setup time. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation, 60, 100804. DOI 10.1016/j.swevo.2020.100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ying, K. C., Lin, S. W., Cheng, C. Y., He, C. D. (2017). Iterated reference greedy algorithm for solving distributed no-idle permutation flowshop scheduling problems. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 110, 413–423. DOI 10.1016/j.cie.2017.06.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hao, J. H., Li, J. Q., Du, Y., Song, M. X., Duan, P. et al. (2019). Solving distributed hybrid flowshop scheduling problems by a hybrid brain storm optimization algorithm. IEEE Access, 7, 66879–66894. DOI 10.1109/Access.6287639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Cai, J., Zhou, R., Lei, D. (2020). Dynamic shuffled frog-leaping algorithm for distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling with multiprocessor tasks. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 90, 103540. DOI 10.1016/j.engappai.2020.103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shao, Z., Shao, H., S, W., Pi, D. C. (2021). Effective constructive heuristic and iterated greedy algorithm for distributed mixed blocking permutation flow-shop scheduling problem. Knowledge-Based Systems, 221, 106959. DOI 10.1016/j.knosys.2021.106959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li, W., Chen, X., Li, J., Sang, H., Han, Y. et al. (2022). An improved iterated greedy algorithm for distributed robotic flowshop scheduling with order constraints. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 164, 107907. DOI 10.1016/j.cie.2021.107907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Jiang, E., Wang, L., Wang, J. (2021). Decomposition-based multi-objective optimization for energy-aware distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling with multiprocessor tasks. Tsinghua Science and Technology, 26(5), 646–663. DOI 10.26599/TST.2021.9010007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Niu, W., Li, J. Q., Jin, H., Qi, R., Sang, H., Y. (2022). Bi-objective optimization using improved NSGA-II for energy-efficient scheduling of distributed assembly blocking flow shop. Engineering Optimization (in press). DOI 10.1080/0305215X.2022.2032017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Qin, H., Li, T., Teng, Y., Wang, K. (2021). Integrated production and distribution scheduling in distributed hybrid flow shops. Memetic Computing, 13(2), 185–202. DOI 10.1007/s12293-021-00329-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Khan, U., Ahmed, N., Mohyud-Din, S. T., Alharbi, S. O., Khan, I. (2022). Thermal improvement in magnetized nanofluid for multiple shapes nanoparticles over radiative rotating disk. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 61(3), 2318–2329. DOI 10.1016/j.aej.2021.07.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Alqahtani, A. M., Khan, U., Ahmed, N., Mohyud-Din, S. T., Khan, I. (2020). Numerical investigation of heat and mass transport in the flow over a magnetized wedge by incorporating the effects of cross-diffusion gradients: Applications in multiple engineering systems. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2020, 2475831. DOI 10.1155/2020/2475831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ahmed, N., Khan, U., Mohyud-Din, S. T., Chu, Y. M., Khan, I., Nisar, K. S. (2020). Radiative colloidal investigation for thermal transport by incorporating the impacts of nanomaterial and molecular diameters (dNanoparticles, dFluidApplications in multiple engineering systems. Molecules, 25(8), 1896. DOI 10.3390/molecules25081896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Pan, Q. K., Wang, L. (2012). Effective heuristics for the blocking flowshop scheduling problem with makespan minimization. Omega, 40(2), 218–229. DOI 10.1016/j.omega.2011.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Na, B., Ahmed, S., Nemhauser, G., Sokol, J. (2013). Optimization of automated float glass lines. International Journal of Production Economics, 145(2), 561–572. DOI 10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.04.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lozano, A. J., Medaglia, A. L. (2014). Scheduling of parallel machines with sequence-dependent batches and product incompatibilities in an automotive glass facility. Journal of Scheduling, 17(6), 521–540. DOI 10.1007/s10951-012-0308-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang, S., Liu, M., Chu, F., Chu, C. (2016). Bi-objective optimization of a single machine batch scheduling problem with energy cost consideration. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137, 1205–1215. DOI 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang, S., Wang, X., Chu, F., Yu, J. (2020). An energy-efficient two-stage hybrid flow shop scheduling problem in a glass production. International Journal of Production Research, 58(8), 2283–2314. DOI 10.1080/00207543.2019.1624857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Li, J., Sang, H., Pan, Q., Duan, P., Gao, K. (2017). Solving multi-area environmental/economic dispatch by pareto-based chemical-reaction optimization algorithm. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, 6(5), 1240–1250. DOI 10.1109/JAS.6570654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Marichelvam, M. K., Prabaharan, T., Yang, X. S. (2014). Improved cuckoo search algorithm for hybrid flow shop scheduling problems to minimize makespan. Applied Soft Computing, 19, 93–101. DOI 10.1016/j.asoc.2014.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Huang, R. H., Yang, C. L., Hsu, C. T. (2015). Multi-objective two-stage multiprocessor flow shop scheduling–a subgroup particle swarm optimisation approach. International Journal of Systems Science, 46(16), 3010–3018. DOI 10.1080/00207721.2014.886742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang, S., Liu, M. (2014). Two-stage hybrid flow shop scheduling with preventive maintenance using multi-objective tabu search method. International Journal of Production Research, 52(5), 1495–1508. DOI 10.1080/00207543.2013.847983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li, J. Q., Liu, Z. M., Li, C., Zheng, Z. X. (2020). Improved artificial immune system algorithm for type-2 fuzzy flexible job shop scheduling problem. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 29(11), 3234–3248. DOI 10.1109/TFUZZ.2020.3016225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li, J. Q., Song, M. X., Wang, L., Duan, P. Y., Han, Y. Y. et al. (2019). Hybrid artificial bee colony algorithm for a parallel batching distributed flow-shop problem with deteriorating jobs. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, 50(6), 2425–2439. DOI 10.1109/TCYB.6221036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Shahvari, O., Logendran, R. (2016). Hybrid flow shop batching and scheduling with a bi-criteria objective. International Journal of Production Economics, 179, 239–258. DOI 10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang, G., Xing, K., Cao, F. (2018). Scheduling distributed flowshops with flexible assembly and set-up time to minimise makespan. International Journal of Production Research, 56(9), 3226–3244. DOI 10.1080/00207543.2017.1401241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang, H., Huang, M., Wang, J. (2019). An effective metaheuristic algorithm for flowshop scheduling with deteriorating jobs. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 30(7), 2733–2742. DOI 10.1007/s10845-018-1425-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li, J. Q., Sang, H. Y., Han, Y. Y., Wang, C. G., Gao, K. Z. (2018). Efficient multi-objective optimization algorithm for hybrid flow shop scheduling problems with setup energy consumptions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 181, 584–598. DOI 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li, J., Chen, X. L., Duan, P., Mou, J. H. (2021). KMOEA: A knowledge-based multi-objective algorithm for distributed hybrid flow shop in a prefabricated system. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 18(8), 5318–5329. DOI 10.1109/TII.2021.3128405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Du, Y., Li, J. Q., Chen, X. L., Duan, P. Y., Pan, Q. K. (2022). Knowledge-based reinforcement learning and estimation of distribution algorithm for flexible job shop scheduling problem. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence, 1–15. DOI 10.1109/TETCI.2022.3145706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mou, J., Duan, P., Gao, L., Liu, X., Li, J. (2022). An effective hybrid collaborative algorithm for energy-efficient distributed permutation flow-shop inverse scheduling. Future Generation Computer Systems, 128, 521–537. DOI 10.1016/j.future.2021.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Li, J. Q., Du, Y., Gao, K. Z., Duan, P. Y., Gong, D. W. et al. (2021). A hybrid iterated greedy algorithm for a crane transportation flexible job shop problem. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, 19(3), 2153–2170. DOI 10.1109/TASE.2021.3062979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen, H., Tian, Y., Pedrycz, W., Wu, G., Wang, R. et al. (2019). Hyperplane assisted evolutionary algorithm for many-objective optimization problems. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, 50(7), 3367–3380. DOI 10.1109/TCYB.6221036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Han, Y., Gong, D., Jin, Y., Pan, Q. (2017). Evolutionary multiobjective blocking lot-streaming flow shop scheduling with machine breakdowns. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, 49(1), 184–197. DOI 10.1109/TCYB.2017.2771213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools