Engineering & Sciences

| Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences |  |

DOI: 10.32604/cmes.2021.015776

ARTICLE

A Simple Cement Hydration Model Considering the Influences of Water-to-Cement Ratio and Mineral Composition

1College of Physics and Electronic Engineering, Yuxi Normal University, Yuxi, 653100, China

2Institute of Mechanics, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, 100044, China

*Corresponding Author: Baoyu Ma. Email: guishenbiyi@yxnu.edu.cn

Received: 12 January 2021; Accepted: 04 March 2021

Abstract: A simple hydration model is used here by taking the composition of the cement and the initial water: cement ratio (w/c) into account explicitly. Its conceptual basis is a combination of the Avrami equation and Bentz’s model based on simple spatial considerations. In this model, the Avrami equation determines the initial reaction, and Bentz’s model describes the following hydration stage. The model favors engineers for it relies on one experimental parameter and has a reliable approximation in the practice.

Keywords: Hydration model; water/cement ratio; composition of the cement; engineering practicability; only one parameter

Modeling cement hydration has both academic and practical values. The hydration kinetics model provides the hydration rate of cement and quantifies the component in the microstructure of cement pasts during the hydration process. In addition, the model can also estimate the aging evolutions of the physical properties. However, the chemical and microstructural phenomena are complex and interdependent, so it is hard to describe the hydration process accurately [1]. Several models with various methods try to quantify the kinetics of hydration [2–4]. Many of the developed models [5–7], with high precision and rigorous argumentation, explicitly consider the effect of kinetic factors, such as cement particle size distribution (PSD), curing temperature, and applied pressure. However, those models, such as the formulas in [6] are very complex and cannot distinguish the rates of reaction to different minerals in Portland cement, and the expressions in [8] require too many correlating parameters, give less consideration to the convenience in engineering applications, become useless tools for field engineers and ready-mix concrete producers. Sometimes, a hydration kinetics model with a critical theoretical system and high accuracy is not necessary, and a simple and easily usable model is indeed adequate [8,9] to evaluate the early-age elastic properties of cement-based materials.

In this paper, a simple hydration kinetics model has been carried out for engineers to estimate the hydration progress only coupled with the influence of composition in the cement and the initial water:cement ratio (w/c). The originality of the proposed approach relies on a combination of the Avrami equation [10] and Bentz’s model [11], along with a hydration model proposed by Tennis et al. [12] that determines the volume fractions of the two types of C-S-H. The model results are compared quantitatively with experimental data.

2.1 A Brief Introduction of Some Existing Hydration Models

To describe and quantify cement hydration, many simple and excellent mathematical approaches have been developed.

Powers model [13,14] was used by several researchers [15,16] because of the easiness of its implementation. It is assumed that the cement paste is composed of three phases: the unhydrated cement grains, the hydrates and the porosity. The hydrates occupy a volume 2.31 times larger than that of the reactants. It also provides the volume fractions of the three ingredients as simple functions of the w/c and of the degree of hydration α. However, it brings a certain lack of precision, as the model cannot take into account the type of cement [16].

The model proposed by Bernard et al. [8] can describe the kinetics of hydration of each clinker phase Xi (i = 1~4, Xi = C3S, C2S, C3A, and C4AF, respectively1) by nucleation, growth, and diffusion laws. It is relatively accurate, although it requires too many parameters.

In recent years, many new technologies and methods are used [17–28]. The Avrami equation [10] is used in some investigations [12,17] to assess the rates of the four dominant compounds in Portland cement, C3S, C2S, C3A, and C4AF. It assumes that the compounds react at similar relative rates:

where

The Avrami equation can well describe nucleation and growth reactions. Although it can not describe the reactions governed by diffusion, it can separate different rates of different minerals [12]. Regrettably, it does not consider the influence of w/c.

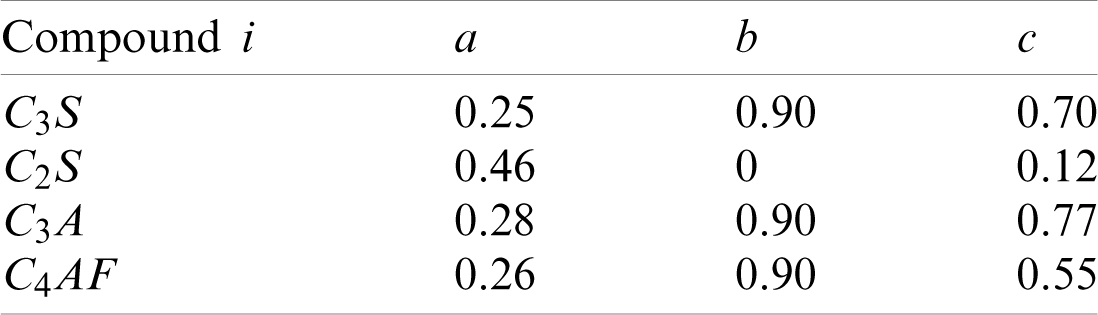

Table 1: Constants used in the Avrami equations [18]

Based on simple spatial considerations, a simple model to describe the hydration kinetics of Portland cement is developed by Bentz [11]:

where

Here, we propose a simple hydration kinetics model based on the respective advantages of the Avrami equation and Bentz’s model. We only take the influence of w/c and the mineralogical components of the cement into our model.

In this model, the Avrami equation determines the initial reaction while Bentz’s model describes the following hydration stage, as shown in the following equations:

where t0 is the junction time joining the two stages, k0, ki are rate constants determined by the degree of hydration of compound i at time t0,

In Eq. (3), due to the limitation of experimental technology and a lack of detailed experimental data, the coefficients in Tab. 1 are still adopted, with k0 as an adjustment coefficient. For the same reasons, it is difficult to determine the different reaction rates of the clinker phases from experimental observations [1,6]. In other words, as

2.3 Determination of the Volume Fractions for All Phases in Hydrating Cement Paste

The hydration reaction equations in [12] determine the quantity of C-S-H and other components in the microstructure of cement pastes. The hydration of the four dominant compounds in Portland cement, C3S, C2S, C3A, and C4AF, is given by [see Eqs. (5)–(10)]:

Besides, the two types of C-S-H model proposed by Tennis et al. [12] is used in this study. Their estimate of the ratio of the mass of low density to the total mass of C-S-H reads, in dried conditions:

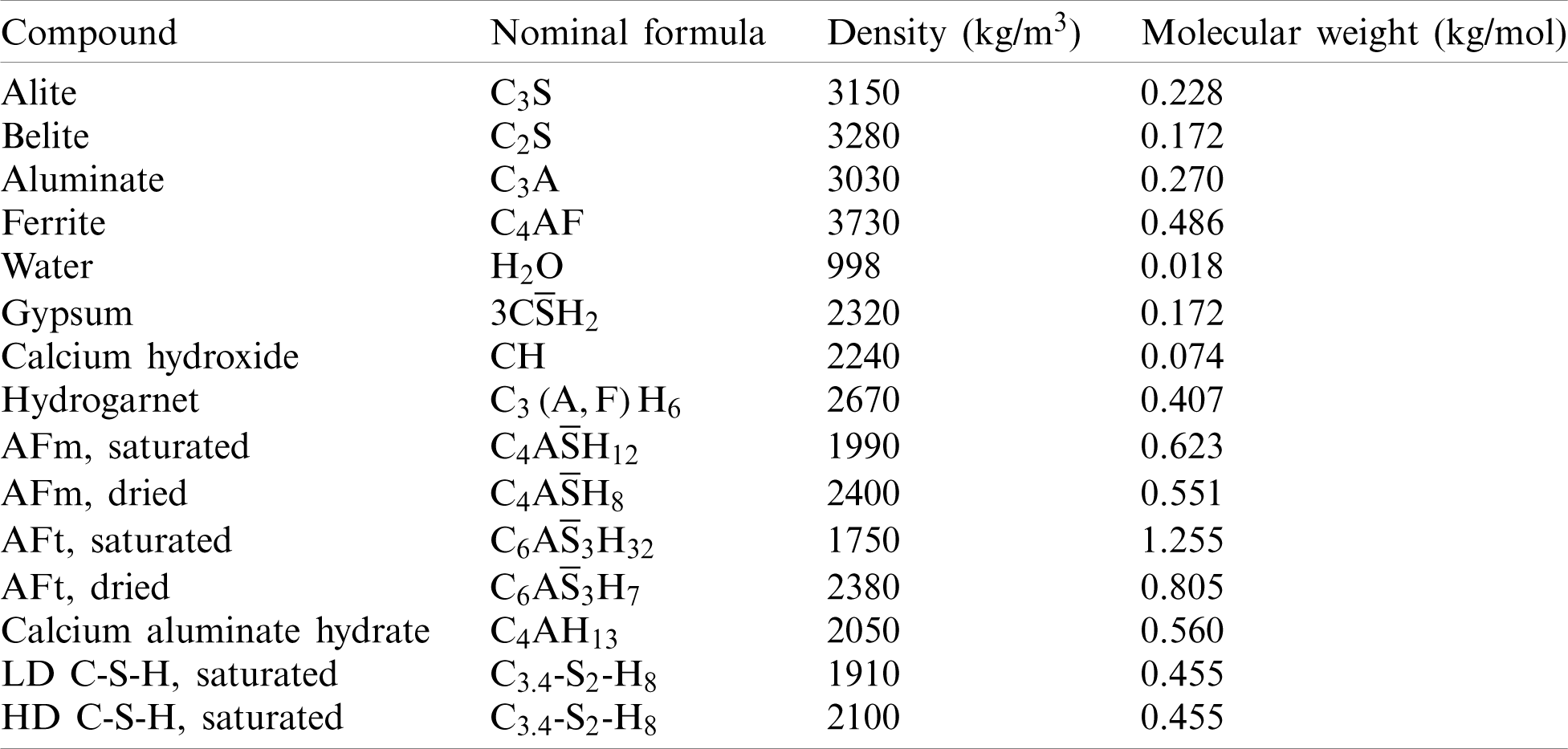

The key parameters of all components in [12] are used in this paper, as shown in Tab. 2.

Noted that the empty porosity is created under sealed curing conditions by the chemical shrinkage occurring during hydration, while in saturated curing conditions, the chemical shrinkage is compensated for by the imbibition of external curing water, thus the total and water-filled porosities are equivalent.

Table 2: The key parameters of all components [12]

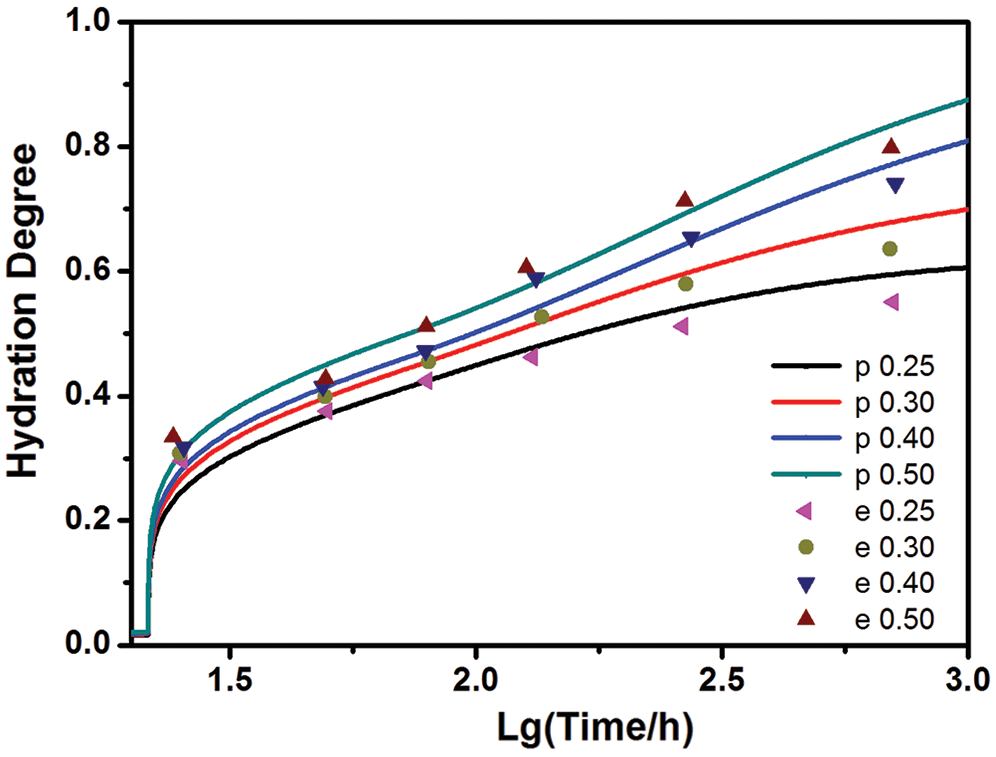

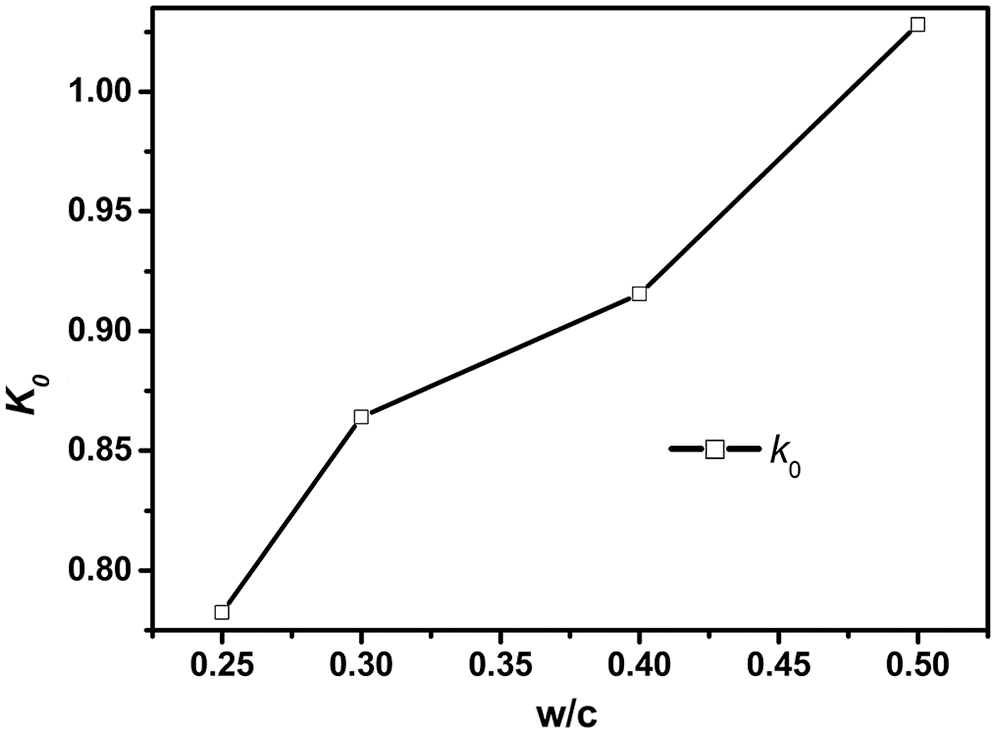

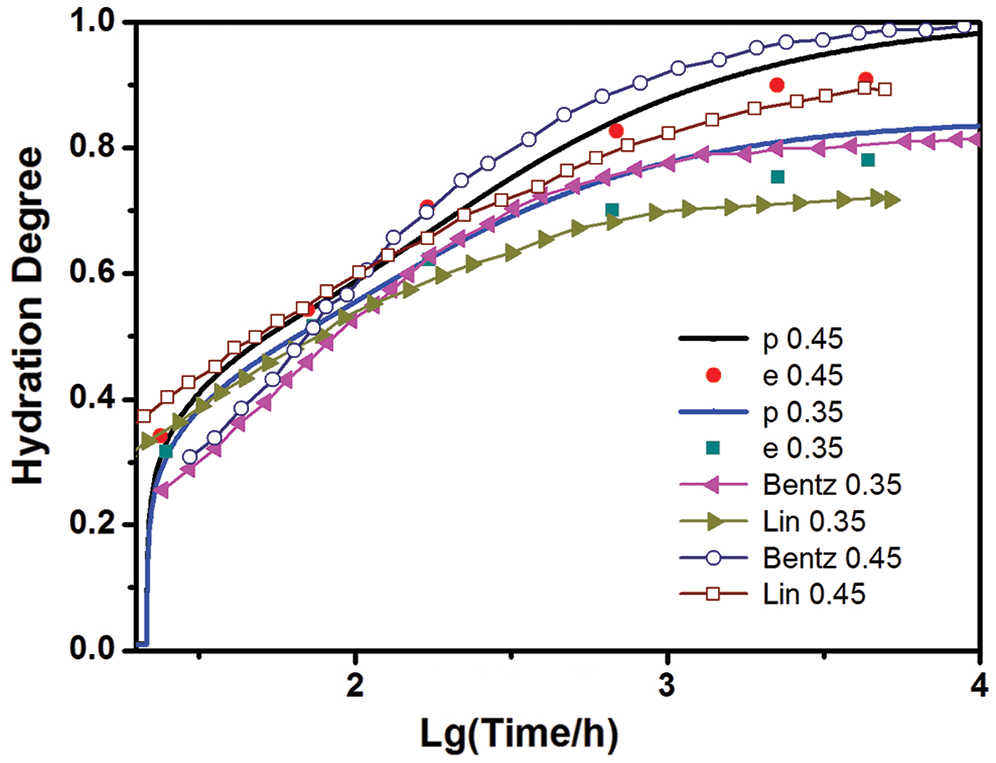

The model results are compared quantitatively with experimental data of [19] in Fig. 1, which shows a reasonably good agreement. It can be seen that the present model is capable of describing the effect of w/c on cement hydration. The values of k0 were determined by the experimentally measured degrees of hydration for several w/c at an age of t0, as shown in Fig. 2. Based on Bentz’s research [11], here t0 = 3 days is applied.

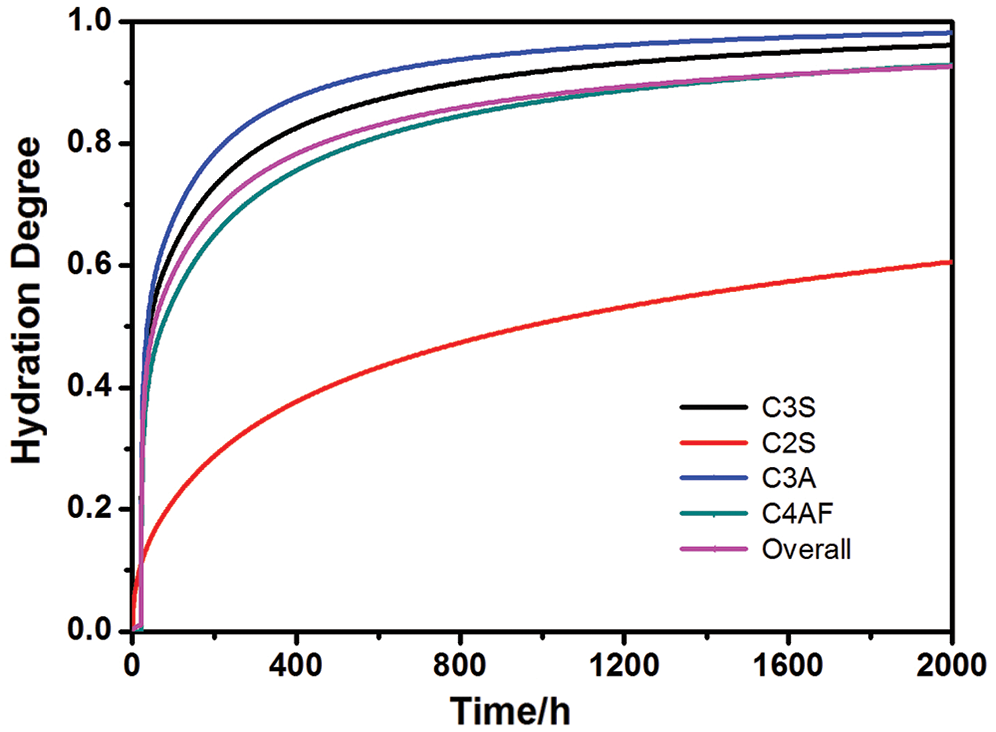

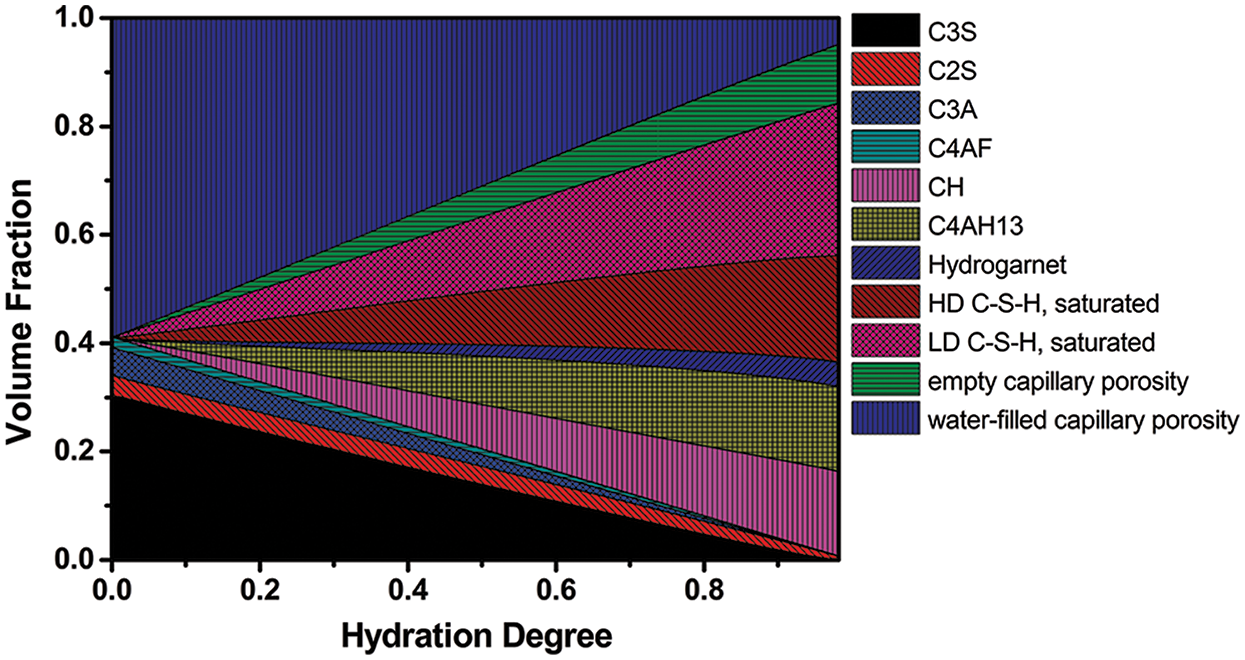

Fig. 3 presents the experimental data in the literature [20] along with the results of the present model and those proposed by Lin [6] and Bentz [11]. It turns out that the present model can provide an adequate quantitative description of the available experimental data. Moreover, while the model in [6,11] can only predict the overall degree, the present model can give separate rates of reaction to different minerals in Portland cement, thus provides the relative volumes of each of the phases in the cement paste, as shown in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. Here the example is for C152 with w/c of 0.45 under sealed curing conditions [20]. Fig. 4 indicates that C3A reacts fastest, followed by C3S and the other two, which is in accordance with the experimental results in the literature [21].

The main advantages of the present approach are easy to use (need only one correlating experimental data) and the capability to provide separate rates of reaction to different minerals. Maybe someone will argue that Eq. (3), a revised Avrami equation, is also adequate but simpler. So we compare Eq. (3) and the present model in Fig. 6, by using the experimental data of [20]. The comparison suggests that the single Eq. (3) cannot describe the later periods for larger slopes, which is owing to the inability of the Avrami equation to describe the more complex reactions governed by diffusion.

Figure 1: The present hydration model results (p) vs. experimental results (e) from [19] with different w/c (t0 = 3)

Figure 2: k0 for different w/c in experiment [19]

Figure 3: The present hydration model results vs. experimental results [20] and others (t0 = 3 days)

Figure 4: The hydration degrees for overall and each of the principal compounds as a function of time

Figure 5: Relative volumes of each of the phases (predicted by the present model) as a function of the degree of hydration

Figure 6: The comparison between Eq. (3) and the present model (t0 = 3 days)

A simple hydration kinetics model for Portland cement has been proposed based on the combination of a revised Avrami equation and the model developed by Bentz, which is on the basis of spatial considerations. The revised Avrami equation is used to describe the early dominant mechanisms of cement hydration, i.e., nucleation and growth reactions, while the later complex reactions governed by diffusion are depicted by Bentz’s model, which is very similar to the expression of the first-order binary homogeneous chemical reaction. The effects of the chemical composition and the water-cement ratio are taken into account in this model. The complex interactions between the four clinker phases are characterized by sharing the same volume fraction of water-filled capillary porosity in Eq. (4).

The comparison between the model results and the experimental data shows that the proposed hydration kinetics model is easy to use and capable of predicting hydration development.

Noted that in the application of the present model, an experimentally measured degree of hydration at an early age (such as 3 days) is required to determine the undetermined parameters, and then the long term hydration development up to a year or more can be obtained. Therefore, the method in this paper has reasonable engineering practicability.

Although the present model has a high value in engineering application with the convenience, it shows some limitations for a lack of rigorous argumentation and comprehensive theoretical analysis of hydration mechanisms. Besides, the present model only considers ordinary Portland cement without any mineral or chemical admixtures. For blended cement or those with admixtures, the interactions between the clinkers and other mineral phases deserve further investigation.

Data Availability Statement: All data used to support this study are included within the article or cited at relevant places within the text as references.

Funding Statement: The work was supported by Yunnan Local Colleges Applied Basic Research Projects (No. 2018FH001-119), Science Research Foundation of Yunnan Education Department of China (Nos. 2019J0734, 2019J0733, 2017ZZX177 and 2018JS422), the Candidate Talents Training Fund of Yunnan Province (Project No. 2015HB064) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11802265).The authors (MBY and QLH) gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Hundred Talents Program of Yuxi (Grant 2019).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1The cement’s chemistry abbreviations will be used in this paper (C3S = 3CaO · SiO2, C2S = 2CaO · SiO2, C3A = 3CaO · Al2O3, C4AF = 4CaO · Al2O3 · Fe2O3).

1. Reardon, E. J. (1992). Problems and approaches to the prediction of the chemical composition in cement/water systems. Waste Management, 12(2–3), 221–239. DOI 10.1016/0956-053X(92)90050-S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Stepišnik, J., Ardelean, I. (2016). Usage of internal magnetic fields to study the early hydration process of cement paste by MGSE method. Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 272(12), 100–107. DOI 10.1016/j.jmr.2016.09.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shen, P., Lu, L., He, Y., Wang, F., Hu, S. (2016). Hydration monitoring and strength prediction of cement-based materials based on the dielectric properties. Construction & Building Materials, 126(1), 179–189. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.09.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Schackow, A., Effting, C., Gomes, I. R., Patruni, I. Z., Vicenzi, F. et al. (2016). Temperature variation in concrete samples due to cement hydration. Applied Thermal Engineering: Design, Processes, Equipment, Economics, 103(1), 1362–1369. DOI 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.05.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Rahimi-Aghdam, S., Bažant, Z. P., Qomi, M. J. A. (2017). Cement hydration from hours to a century controlled by diffusion through barrier shells of C-S-H. Journal of the Mechanics & Physics of Solids, 99(1), 211–224. DOI 10.1016/j.jmps.2016.10.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lin, F., Meyer, C. (2009). Hydration kinetics modeling of Portland cement considering the effects of curing temperature and applied pressure. Cement & Concrete Research, 39(4), 255–265. DOI 10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang, X. Y., Lee, H. S. (2012). Modeling of hydration kinetics in cement based materials considering the effects of curing temperature and applied pressure. Construction and Building Materials, 28(1), 1–13. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.08.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bernard, O., Ulm, F. J., Lemarchand, E. (2003). A multiscale micromechanics-hydration model for the early-age elastic properties of cement-based materials. Cement & Concrete Research, 33(9), 1293–1309. DOI 10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00039-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shatat, M. R. (2013). Hydration behavior and mechanical properties of blended cement containing various amounts of rice husk ash in presence of metakaolin. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 9(2), 1869–1874. DOI 10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dalziel, J. A., Gutteridge, W. A. (1986). The influence of pulverized-fuel ash upon the hydration characteristics and certain physical properties of a Portland cement paste. Cement & Concrete Association Technicall Report, 560. [Google Scholar]

11. Bentz, D. P. (2006). Influence of water-to-cement ratio on hydration kinetics: Simple models based on spatial considerations. Cement & Concrete Research, 36(2), 238–244. DOI 10.1016/j.cemconres.2005.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tennis, P. D., Jennings, H. M. (2000). A model for two types of calcium silicate hydrate in the microstructure of portland cement pastes. Cement and Concrete Research, 30(6), 855–863. DOI 10.1016/S0008-8846(00)00257-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hansen, T. C. (1986). Physical structure of hardened cement paste. A classical approach. Materials & Structures, 19(6), 423–436. DOI 10.1007/BF02472146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Powers, T. C. (1958). Studies of the physical properties of hardened Portland cement paste. Journal of the American Ceramic Societys, 41(1), 1–6. DOI 10.1111/j.1151-2916.1958.tb13494.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Igarashi, S., Kawamura, M., Watanabe, A. (2004). Analysis of cement pastes and mortars by a combination of backscatter-based SEM image analysis and calculations based on the powers model. Cement & Concrete Composites, 26(8), 977–985. DOI 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2004.02.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Stefan, L., Benboudjema, F., Torrenti, J. M., Bissonnette, B. (2010). Prediction of elastic properties of cement pastes at early ages. Computational Materials Science, 47(3), 775–784. DOI 10.1016/j.commatsci.2009.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lin, F., Meyer, C. (2007). Micromechanics model for the effective elastic properties of hardened cement pastes. Fuhe Cailiao Xuebao/Acta Materiae Compositae Sinica (in Chinese), 24(2), 184–189. DOI 10.1007/s10870-007-9222-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Taylor, H. F. W. (1987). A method for predicting alkazi ion concentrations in cement pore solutions. Advances in Cement Research, 1(1), 5–17. DOI 10.1680/adcr.1987.1.1.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Danielson, U. (1960). Heat of hydration of cement as affected by water-cement ratio. Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on the Chemistry of Cement, pp. 519–526, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

20. Cement and and Concrete Reference Laboratory (2004). Cement and concrete reference laboratory proficiency sample program: Final report on Portland cement proficiency samples number 151 and 152. Gaithersburg, MD. [Google Scholar]

21. Escalante-Garcia, J. I., Sharp, J. H. (1998). Effect of temperature on the hydration of the main clinker phases in Portland Cements: Part I, neat cements. Cement & Concrete Research, 28(9), 1245–1257. DOI 10.1016/S0008-8846(98)00115-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Holmes, N., Kelliher, D., Tyrer, M. (2020). Simulating cement hydration using Hydcem. Construction and Building Materials, 239(4), 117811. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wu, L., Yan, R. Y., Cai, J. Y., Yue, W. X. (2020). Hydration kinetics model of rice husk ash-blended system. Key Engineering Materials, 842, 306–313. DOI 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.842.306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sera, I. (2020). Sequential diffusion spectra as a tool for studying time-dependent translational molecular dynamics: A cement hydration study. Molecules, 25(1), 68–83. DOI 10.3390/molecules25010068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kim, H. S., Park, D. W., Oh, G. H., Kim, H. S. (2021). Non-destructive evaluation of cement hydration with pulsed and continuous terahertz electro-magnetic waves. Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 138, 106414. DOI 10.1016/j.optlaseng.2020.106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Qi, T., Zhou, W., Liu, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, S. (2021). Predictive hydration model of Portland cement and its main minerals based on dissolution theory and water diffusion theory. Materials, 14(3), 595. DOI 10.3390/ma14030595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chu, L., Dui, G., Zheng, Y. (2020). Thermally induced nonlinear dynamic analysis of temperature-dependent functionally graded flexoelectric nanobeams based on nonlocal simplified strain gradient elasticity theory. European Journal of Mechanics-A/Solids, 82(3), 103999. DOI 10.1016/j.euromechsol.2020.103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chu, L., Li, Y., Dui, G. (2019). Nonlinear analysis of functionally graded flexoelectric nanoscale energy harvesters. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 167(8), 105282. DOI 10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2019.105282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |