Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Safety of nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg: review of data from phase 2 and phase 3 studies

1 Department of Urology, University of Minnesota and Allina Health Cancer Institute, Minneapolis, MN 55407, USA

2 Department of Urology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

3 Department of Urology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA

* Corresponding Author: Badrinath R. Konety. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(1), 29-36. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064710

Received 09 December 2024; Accepted 21 February 2025; Issue published 20 March 2025

Abstract

Introduction: Non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is a common malignancy worldwide. While Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is standard of care for treatment for most patients with high-risk NMIBC, many will either not respond to BCG initially or will eventually develop BCG-unresponsive disease. A treatment option in BCG-unresponsive disease is nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg (Adstiladrin), a nonreplicating adenoviral vector–based gene therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of adults with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with carcinoma in situ with or without papillary tumors. Objective: To review safety outcomes of participants who received the FDA-approved dose of nadofaragene firadenovec (3 × 1011 vp/mL) across phase 2 (NCT01687244) and phase 3 (NCT02773849) studies. Methods: Data from the phase 2 and phase 3 studies were collected and analyzed. The findings were reported using descriptive statistics to summarize the key outcomes observed across studies. Results: Common adverse events (AEs) among nadofaragene firadenovec recipients were leakage of fluid around the urinary catheter, fatigue, bladder spasm, chills, dysuria, and micturition urgency. Most study drug–related AEs were mild and localized, with no grade 4 or 5 study drug–related AEs observed in either study. Study drug–related AEs were generally transient, with most study drug–related AEs having a median duration of ≤2.0 days in the phase 3 study. Discontinuation rates due to study drug–related AEs were low, with none (0%) in the phase 2 study and three (1.9%) in the phase 3 study. No specific postmarketing surveillance was required by the FDA besides routine pharmacovigilance monitoring; no new real-world safety signals have been observed. Conclusion: Nadofaragene firadenovec demonstrated a favorable and tolerable safety profile across its clinical study program, allowing for broad patient selection among those with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC.Keywords

Bladder cancer ranks as the ninth most common cancer globally and the sixth most common cancer in the United States.1,2 Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy has been the cornerstone of treatment for non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) for several decades, with initial complete response rates varying between 55% and 65% for papillary tumors and 70% to 75% for carcinoma in situ (CIS).3,4 However, despite high initial response rates, a substantial proportion of patients may experience recurrence and progression of disease during long-term follow-up, ultimately becoming BCG unresponsive.4,5 Radical cystectomy is considered definitive treatment in the setting of BCG-unresponsive disease; the invasive nature and the accompanying morbidity and mortality make it unsuitable for certain patients.6–8 In addition, many patients prefer to forgo or delay radical cystectomy to avoid potential lifelong consequences of the procedure and the resultant decreases in health-related quality of life.9 Bladder-preserving treatment options are essential for patients who cannot undergo or prefer to avoid radical cystectomy. While four therapies are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS with or without papillary tumors, a global unmet need remains.10–15

Nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg (rAd-IFNα/Syn3; Ferring Pharmaceuticals A/S) is an intravesical gene therapy approved by the FDA for patients with high-risk BCG-unresponsive NMIBC with CIS with or without papillary tumors.13 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines also support the use of nadofaragene firadenovec in select patients with high-grade papillary Ta/T1 only tumors without CIS.6 Nadofaragene firadenovec consists of rAd-IFNα, a nonreplicating adenoviral vector–based gene therapy that delivers the gene encoding human IFNα2b to uroepithelial cells of the bladder wall. The drug formulation also contains Syn3, a polyamide surfactant that enhances viral transduction of the urothelium.16–19 Expression of IFNα2b protein causes antitumor effects through various mechanisms, which include cytotoxic, immune-mediated, and antiangiogenic effects.20 Across four clinical studies, more than 200 participants have been treated with nadofaragene firadenovec.21–24

Nadofaragene firadenovec is an effective therapy for patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, with more than half of participants with CIS ± Ta/T1 tumors experiencing a complete response within 3 months of a single dose in the phase 3 CS-003 study.23 The phase 2 (NCT01687244) and phase 3 (NCT02773849) studies included prespecified safety endpoints, with monitoring periods of 4 years and 5 years following administration of the first dose of nadofaragene firadenovec, respectively. This brief report reviews the clinical safety data of nadofaragene firadenovec across the phase 2 and phase 3 studies.22–24

Safety of Nadofaragene Firadenovec

Methods of phase 2 and phase 3 studies

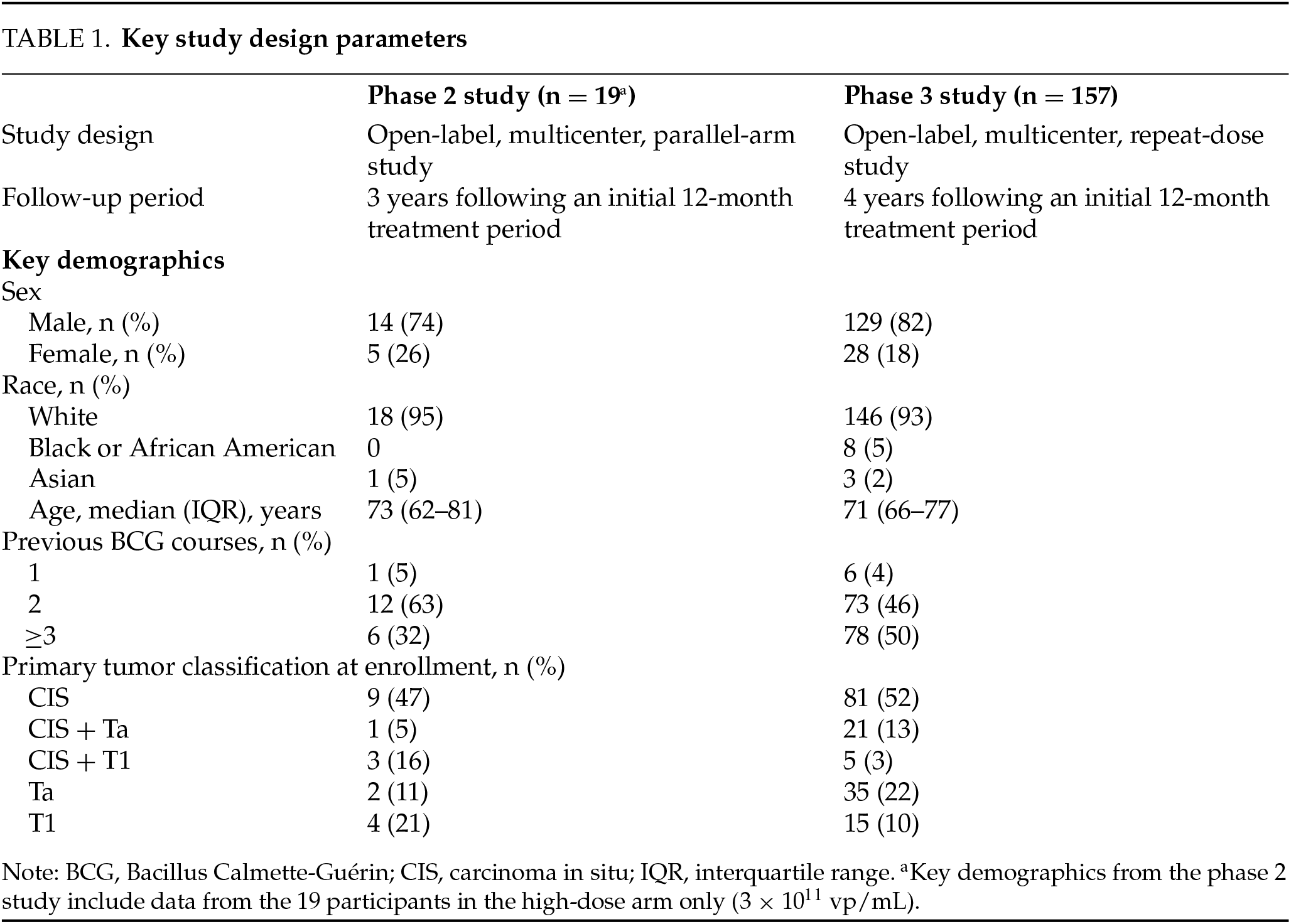

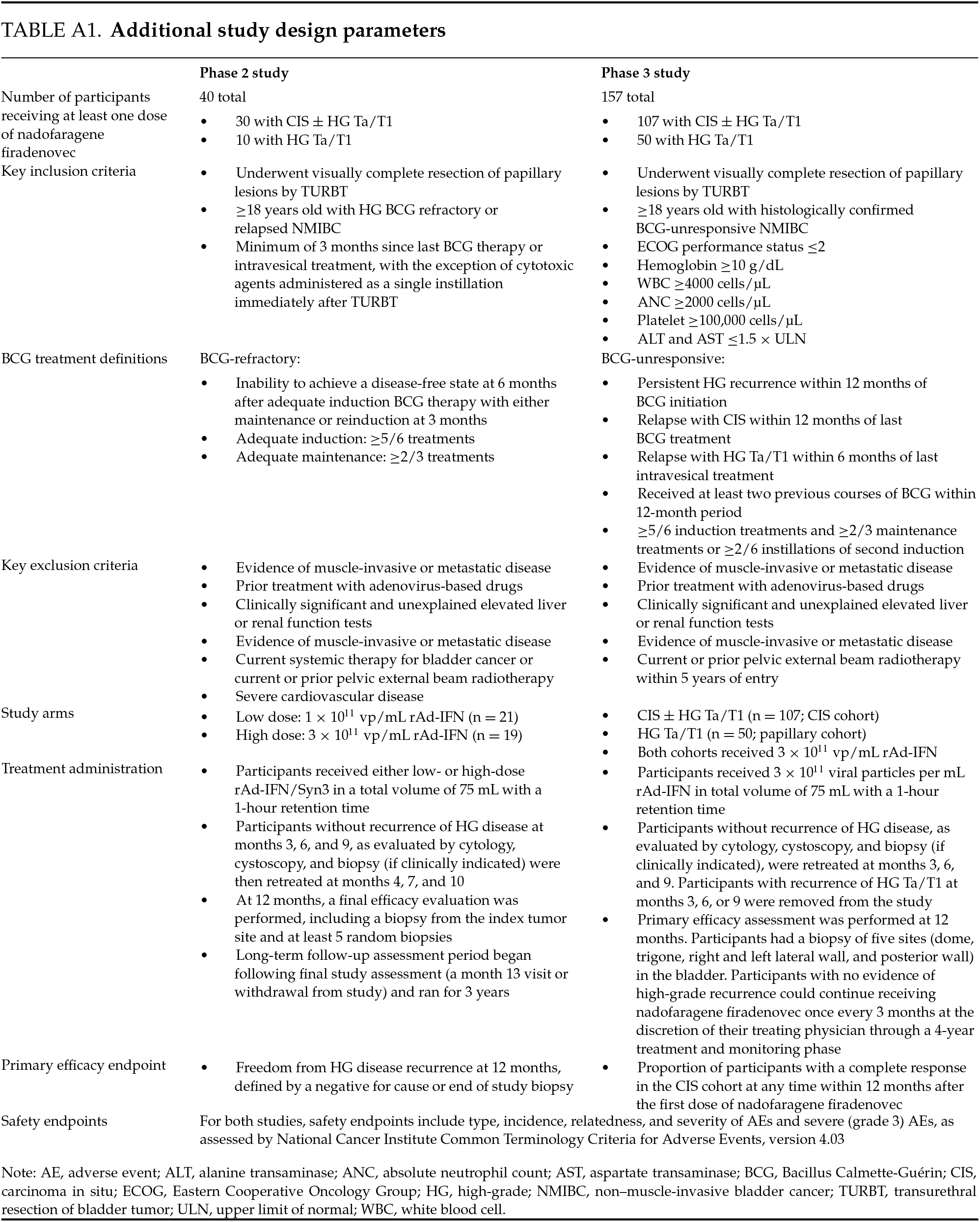

Key study demographics from the phase 2 and phase 3 studies are reported in Table 1, and key study parameters are reported in Table A1. The phase 2 study enrolled participants with CIS (with or without high-grade Ta/T1) and high-grade Ta/T1 only and assigned them to low- and high-dose treatment arms of 1 × 1011 vp/mL and 3 × 1011 vp/mL, respectively. Participants were monitored for 4 years following administration of the first dose of nadofaragene firadenovec, with prespecified safety endpoints (Table 1). All adverse events (AEs) were documented for up to 12 months, after which only serious study drug–related AEs and/or procedure-related AEs were collected. Based on the clinical safety and efficacy profile of the high-dose (3 × 1011 vp/mL) arm in the phase 2 study, this dosage was used in the single-arm CS-003 phase 3 study, which enrolled participants into two cohorts: CIS (with or without high-grade Ta/T1) and high-grade Ta/T1 only. Participants in the phase 3 study were monitored for 5 years after administration of the first dose of nadofaragene firadenovec, with prespecified safety endpoints. All AEs were documented for up to 24 months, after which only serious study drug–related and/or procedure-related AEs were collected. For patients who had disease progression and agreed, follow-up data on long-term survival and time to cystectomy was collected annually for up to 5 years or until consent was withdrawn. For all patients, serious adverse events (SAEs) were followed up until resolution and AEs were followed up for a maximum of 30 days after the withdrawal from study visit. For both studies, an AE was protocol-defined as any untoward medical occurrence associated with the use of a drug in humans. An AE was defined as serious if it resulted in death, was life-threatening, resulted in hospitalization, caused a significant disruption in normal life functions, caused a congenital anomaly or birth defect, or jeopardized the participant and required intervention to prevent a negative outcome. All AEs and SAEs were assessed for relationship to the study drug or study procedure. The severity of each AE was graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03.

Full methods, statistical analyses, and outcomes for each study have been reported previously.22–24 To better describe data across multiple studies, the safety data reported here include only participants who received the same FDA-approved dose of 3 × 1011 vp/mL.

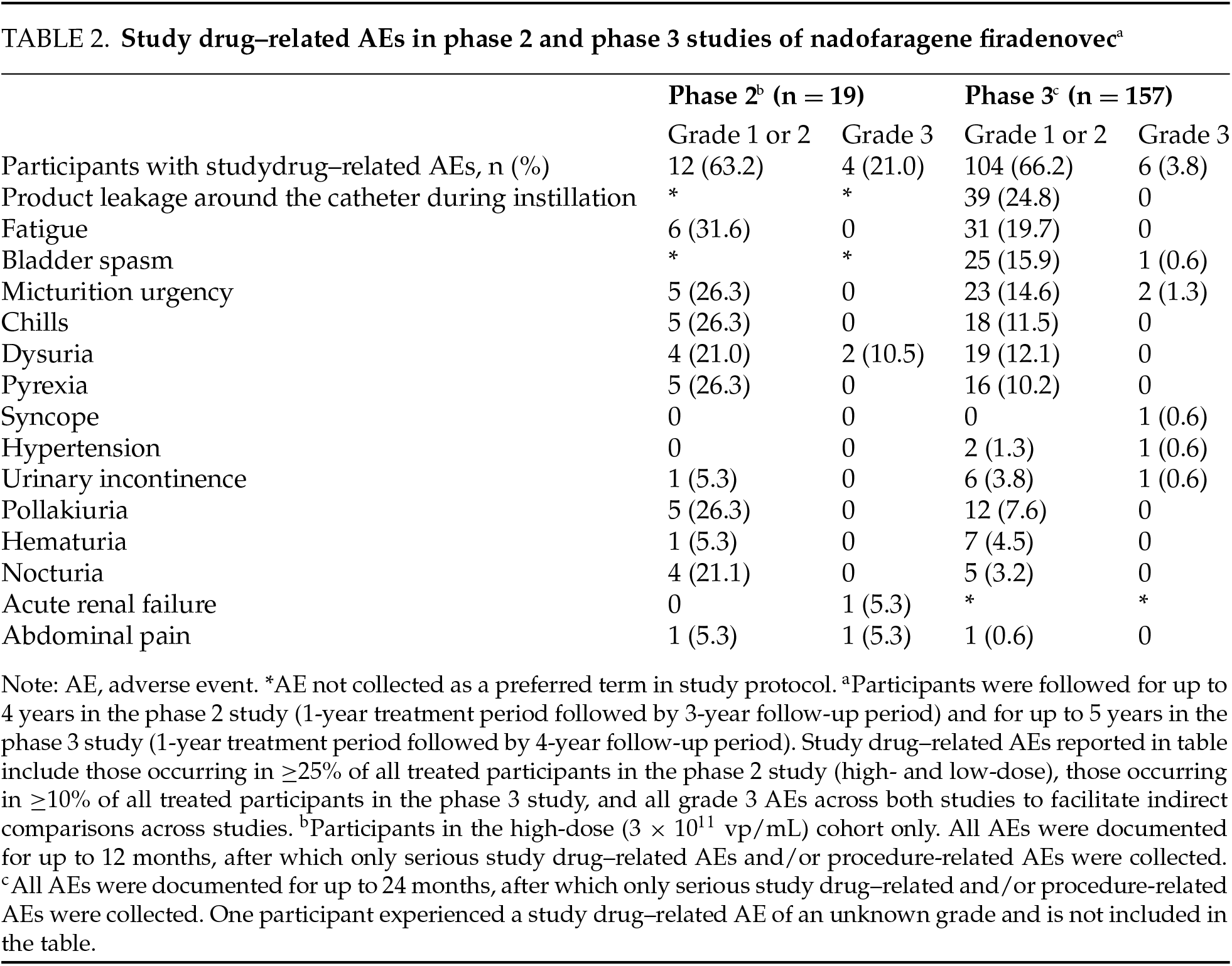

Nineteen participants received at least one dose of nadofaragene firadenovec 3 × 1011 vp/mL in the phase 2 study. Among these, all 19 (100%) experienced at least one AE, with the highest AE severity being grade 1 or 2 for most participants (84.2%). There were four grade 3 study drug–related events (abdominal pain, dysuria [n = 2], and acute renal failure) reported in three participants (15.8%); no grade 4 or 5 AEs were reported.

Sixteen participants (84.2%) reported at least one study drug–related AE. The most common study drug–related AEs included fatigue, micturition urgency, dysuria, and chills (Table 2). Two participants (10.5%) experienced a total of two grade 3 SAEs, of which one was related to study drug (acute renal failure), which resolved with routine medical care. All SAEs occurred only once. There were no dose interruptions or discontinuations that were attributed to a study drug–related AE. One participant discontinued treatment due to a grade 3 SAE, which was assessed to be a symptom of disease progression and unrelated to study drug administration. There were no recorded SAEs deemed to be treatment related following the initial 12-month treatment period for up to 3 years of follow-up. No deaths were assessed as related to nadofaragene firadenovec during long-term follow-up.

No clinically significant changes in mean values of laboratory parameters or vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG) findings, or physical examination were found over the course of the study. Participants in the low-dose arm demonstrated similar rates of AEs, with no additional safety signals reported.

Phase 3 study results (CS-003)

A total of 157 participants (CIS ± Ta/T1 cohort, n = 107 participants; high-grade Ta/T1 only cohort, n = 50 participants) received at least one dose of nadofaragene firadenovec 3 × 1011 vp/mL. Of these, 42 participants (26.8%) continued treatment after 12 months, and 31 participants (19.7%) continued treatment at or after 24 months. Among the safety population (N = 157), 146 participants (93.0%) experienced an AE: 101 in the CIS cohort and 45 in the high-grade Ta/T1 cohort. There were 58 participants (36.9%) with dose interruptions, with 54 dose interruptions (34.4%) involving an AE. Study drug–related AEs were experienced by 111 participants (70.7%) (Table 2). Most study drug–related AEs were transient and grade 1 or 2 in severity. There were only six grade 3 study drug–related events (two cases of micturition urgency and one case each of bladder spasm, urinary incontinence, syncope, and hypertension).

The most common study drug–related AEs included leakage of fluid around the catheter during instillation (24.8%), fatigue (19.7%), and bladder spasm (16.5%). There were no grade 4 or 5 study drug–related AEs, and most study drug–related AEs were of a short median duration (≤2.0 days). In total, 79 (50.3%) participants had a study procedure–related AE. The most common study procedure–related AEs included leakage of fluid around the urinary catheter (20.4%), bladder spasm (10.2%), and micturition urgency (7.6%). Study procedure–related AEs had a short median duration of ≤1.0 day.

SAEs were reported in 19 participants (12.1%). One SAE was assessed as being related to study drug by the investigator but not by the sponsor (syncope). Three SAEs were related to study procedure (one case each of sepsis, pyrexia, and hematuria). Only three participants (1.9%) discontinued treatment due to a study drug–related AE (grade 3 bladder spasm, grade 2 instillation site discharge, grade 2 benign neoplasm of the bladder); none of these events were assessed as being serious. Laboratory parameters were collected as part of routine safety monitoring, and transient abnormalities in blood glucose, triglycerides, creatine, phosphate, and hemoglobin were reported. However, these changes were largely not deemed clinically significant by site investigators. There were also no notable changes in vital signs, ECG parameters, or physical examination results across either cohort. No new safety signals were observed following the initial 12-month treatment period and for up to 4 years of follow up, and no deaths were assessed as being related to nadofaragene firadenovec.

Nadofaragene firadenovec was approved for use in the United States in December of 2022. Since market authorization, all reported side effects have been mild, nonserious, and consistent with experience in the phase 2 and phase 3 studies.

Safe and efficacious bladder-preserving treatments for NMIBC represent a global unmet need because there are few available options approved worldwide for patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC who are not eligible for or who are unwilling to undergo radical cystectomy. Patient factors such as risk group, comorbidities, and intolerances are all considerations when selecting treatment for NMIBC, and well-tolerated therapies help alleviate concerns about AEs. Nadofaragene firadenovec was well tolerated, with mild grade 1 or 2 study drug–related AEs reported for most participants, and no grade 4 or 5 study drug–related AEs observed in phase 2 or phase 3 clinical studies with up to 4 years of follow-up following the initial one-year treatment period. The median duration of AEs was generally short, with the majority of study drug–related AEs having a median duration of ≤2 days in the phase 3 study. No study drug–related AEs led to discontinuation in the phase 2 study and only three (1.9%) discontinuations were seen due to study drug–related AEs in the phase 3 study.

Since nadofaragene firadenovec is administered intravesically, most AEs were limited to transient bladder–related events. Several bladder–related AEs such as pollakiuria, urinary urgency, hematuria, and bladder spasm have been observed in studies of other intravesically administered therapies such as BCG, gemcitabine, and docetaxel, suggesting some of these AEs may be characteristic of intravesical administration as a whole.25,26 Some AEs may be mitigated with supportive medical therapy, such as premedication with an anticholinergic agent to prevent urinary urgency, fully thawing the medication and allowing it to come to room temperature (as cold fluids may cause bladder spasms), and appropriate catheterization techniques to avoid bladder pain and hematuria.13

There were no reports of grade 4 or 5 study drug-related AEs during the treatment or monitoring phases in either the phase 2 or 3 clinical studies of nadofaragene firadenovec, with a median duration of follow-up in the phase 3 study of 50.8 months. Importantly, no additional risk mitigation measures and safety–related postmarketing requirements were imposed by the FDA beyond appropriate labeling and routine pharmacovigilance activities.27

A potential concern is that delaying cystectomy could lead to the development of muscle-invasive or metastatic bladder cancer. The rate of progression to muscle-invasive disease during long-term follow-up was 16% (3 of 19 participants in the high-dose arm) in the phase 2 study and 3% (5 of 151 participants in the efficacy analysis set) in the phase 3 study. In the phase 2 study, reports of progression were collected after treatment discontinuation and after first recurrence of high-grade disease, while in the phase 3 study, reports of progression were collected only at the time of first disease recurrence and not at any time point afterwards. Therefore, the number of reports of progression cannot be compared between the studies. However, the low rate of muscle-invasive progression in the phase 3 study suggests nadofaragene firadenovec did not put participants at increased risk for progression and subsequent death from delayed cystectomy.23

This analysis is a retrospective report of safety data from phase 2 and phase 3 studies. Due to differences in methodology and data collection parameters between the two studies, an integrated safety analysis and direct comparisons were not conducted. Detailed AE profiles after study drug administration were available for up to 1 year after the first dose in the phase 2 study and up to 2 years after the first dose in the phase 3 study, after which only SAEs related to the study drug were collected.

In summary, this safety review highlights nadofaragene firadenovec as a safe and well-tolerated bladder-preserving therapeutic option for patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC. Continued research on real-world safety, patterns of use, and patient and provider experiences with nadofaragene firadenovec is ongoing in the phase 4 ABLE-41 study (NCT06026332).28

Acknowledgement

Medical writing support, under the guidance of the authors, was provided by ApotheCom (Yardley, PA, USA), and was funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Parsippany, NJ, USA). Contributions to manuscript conceptualization, review, and development were also provided by Francis Emmanuel Crisostomo, MD (Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Parsippany, NJ, USA).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Author Contributions

Badrinath R. Konety: Conception, performance of work, interpretation of data, writing the article. Yair Lotan: Conception, performance of work, interpretation of data, writing the article. Amanda Myers: Conception, performance of work, interpretation of data, writing the article. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Inc., will provide access to data upon reasonable request via a secure portal, to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, while ensuring compliance to patient privacy regulations. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Ferring.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare the following potential conflicts of interest relating to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Badrinath R. Konety: served as a consultant/advisor and received funding from Photocure, Asieris Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc., Illumina, Inc., and Abbott and has ownership/investment interest in Astrin Biosciences and Styx Biotechnologies. Yair Lotan: served as a consultant/advisor and received funding from Pacific Edge, Photocure, AstraZeneca, Vessi Medical, Nucleix, Merck, Engene, CAPS Medical, C2i Genomics, FerGene, AbbVie, Ambu, Seattle Genetics, Verity Pharmaceuticals, Urogen, Stimit, Nanorobot, Convergent Genomics, Aura Biosciences, Nonagen, Valar Lab, Pfizer, Phinomics, CG Oncology, Virtuoso Surgical, XCures, Uroviu, On Target Lab, Promis Diagnostics, and Uroessentials. YL received funds for involvement with data monitoring and safety committee from Urogen. YL discloses nonfinancial scientific study or trial involvement with FKD, MDxHealth, and GenomeDx Biosciences Inc. Amanda Myers: served as a consultant/advisor for Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Appendix A

References

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 2023;73(1):17–48. doi:10.3322/caac.21763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74(3):229–263. doi:10.3322/caac.21834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Narayan VM, Dinney CPN. Intravesical gene therapy. Urol Clin North Am 2020;47(1):93–101. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2019.09.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD et al. Maintenance Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol 2000;163(4):1124–1129. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67707-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lerner SP, Dinney C, Kamat A et al. Clarification of bladder cancer disease states following treatment of patients with intravesical BCG. Bladder Cancer 2015;1(1):29–30. doi:10.3233/BLC-159002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Bladder Cancer. Version 4.2024 Plymouth Meeting, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2024. [updated 05/09/2024]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. Shabsigh A, Korets R, Vora KC et al. Defining early morbidity of radical cystectomy for patients with bladder cancer using a standardized reporting methodology. Eur Urol 2009;55(1):164–174. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Stimson CJ, Chang SS, Barocas DA et al. Early and late perioperative outcomes following radical cystectomy: 90-day readmissions, morbidity and mortality in a contemporary series. J Urol 2010;184(4):1296–1300. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Collacott H, Krucien N, Heidenreich S, Catto JWF, Ghatnekar O. Patient preferences for treatment of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a cross-country choice experiment. Eur Urol Open Sci 2023;49:92–99. doi:10.1016/j.euros.2022.12.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chang SS, Boorjian SA, Chou R et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO guideline. J Urol 2016;196(4):1021–1029. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Holzbeierlein JM, Bixler BR, Buckley DI et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO guideline: 2024 amendment. J Urol 2024;211(4):533–538. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) injection, for intravenous use [package insert]. Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc; 2024. [Google Scholar]

13. ADSTILADRIN® (nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg) suspension, for intravesical use. Kastrup, Denmark: Ferring Pharmaceuticals; 2022. [Google Scholar]

14. VALSTAR® (valrubicin) solution, for intravesical use [package insert]. Malvern, PA: Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2019. [Google Scholar]

15. ANKTIVA® (nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln) solution, for intravesical use [package insert]. Culver City, CA: ImmunityBio Inc; 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. Benedict WF, Tao Z, Kim CS et al. Intravesical Ad-IFNalpha causes marked regression of human bladder cancer growing orthotopically in nude mice and overcomes resistance to IFN-alpha protein. Mol Ther 2004;10(3):525–532. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tao Z, Connor RJ, Ashoori F et al. Efficacy of a single intravesical treatment with Ad-IFN/Syn 3 is dependent on dose and urine IFN concentration obtained: implications for clinical investigation. Cancer Gene Ther 2006;13(2):125–130. doi:10.1038/sj.cgt.7700865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Connor RJ, Anderson JM, Machemer T, Maneval DC, Engler H. Sustained intravesical interferon protein exposure is achieved using an adenoviral-mediated gene delivery system: a study in rats evaluating dosing regimens. Urology 2005;66(1):224–229. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.02.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yamashita M, Rosser CJ, Zhou JH et al. Syn3 provides high levels of intravesical adenoviral-mediated gene transfer for gene therapy of genetically altered urothelium and superficial bladder cancer. Cancer Gene Ther 2002;9(8):687–691. doi:10.1038/sj.cgt.7700488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Narayan VM, Meeks JJ, Jakobsen JS, Shore ND, Sant GR, Konety BR. Mechanism of action of nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg. Front Oncol 2024;14:1359725. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1359725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dinney CPN, Fisher MB, Navai N et al. Phase I trial of intravesical recombinant adenovirus mediated interferon-α2b formulated in Syn3 for Bacillus Calmette-Guérin failures in nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol 2013;190(3):850–856. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shore ND, Boorjian SA, Canter DJ et al. Intravesical rAd-IFNα/Syn3 for patients with high-grade, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin-refractory or relapsed non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a phase II randomized study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(30):3410–3416. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Boorjian SA, Alemozaffar M, Konety BR et al. Intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec gene therapy for BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a single-arm, open-label, repeat-dose clinical trial. Lancet Oncol 2021;22(1):107–117. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30540-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Narayan VM, Boorjian SA, Alemozaffar M et al. Efficacy of intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec for patients with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin-unresponsive nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: 5-year follow-up from a phase 3 trial. J Urol 2024;212(1):74–86. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000004020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Decaestecker K, Oosterlinck W. Managing the adverse events of intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. Res Rep Urol 2015;7:157–163. doi:10.2147/RRU.S63448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. McElree IM, Steinberg RL, Mott SL, O’Donnell MA, Packiam VT. Comparison of sequential intravesical gemcitabine and docetaxel vs Bacillus Calmette-Guérin for the treatment of patients with high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6(2):e230849. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sharma A. Summary basis for regulatory action. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2022. [updated 12/16/2022]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/164532/download. [Google Scholar]

28. Daneshmand S, Shore ND, Scholz K et al. ABLE-41: nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg early use and outcomes in a real-world setting in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2024;42(4_suppl):TPS705. doi:10.1200/JCO.2024.42.4_suppl.TPS705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools