Open Access

Open Access

CASE REPORT

Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm of the bladder with peritoneal metastasis

1 Department of Urology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA

2 Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA

3 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA

* Corresponding Author: Peter J. Arnold. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(1), 47-53. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064694

Received 15 September 2024; Accepted 30 December 2024; Issue published 20 March 2025

Abstract

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) are a diverse group of mesenchymal neoplasms. While they have been described throughout the genitourinary system, PEComas are quite rare within the bladder. We present the case of a 37-year-old male who presented in clot retention and was found to have a bladder PEComa. Staging images seemingly demonstrated solid tumor confinement to the bladder and pelvis. Intraoperative pathology revealed peritoneal metastasis. The patient underwent a pelvic mass excision and partial cystectomy. The patient had plans for adjuvant chemotherapy, but later returned to the hospital and passed away from acute hypoxic respiratory failure.Keywords

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas), first described by Bonetti and colleagues in the early 1990s, represent a rare subset of mesenchymal neoplasms that arise from perivascular epithelial cells.1,2 This group includes clear cell “sugar” tumors, angiomyolipomas, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, and other perivascular epithelioid cell-derived tumors.1–4 PEComas are immunoreactive for both melanocytic and smooth muscle markers and are typically found around blood vessels, where they appear to contribute to vessel walls.1,2

The most common locations where PEComas have been documented include the liver, kidneys, soft tissue, and lungs. Within the genitourinary tract, PEComas have been reported in the prostate, testis, kidney, urethra, and the bladder.2 In children, albeit rare, PEComas have been associated with tuberous sclerosis complex.1,2 PEComas generally show a higher incidence among women compared to men, with a 5:1 ratio, and typically occur in the fifth and sixth decades of life. However, bladder PEComas tend to present earlier in the third or fourth decade of life with no significant gender differences.2–6 Patients vary in presentation. Hematuria is the most common complaint, with urinary hesitancy, urinary urgency, polyuria, abdominal pain, and abdominal distension also being reported.2–6 There have also been a few asymptomatic cases where PEComas of the bladder were found incidentally via imaging studies for workup of other presentations.

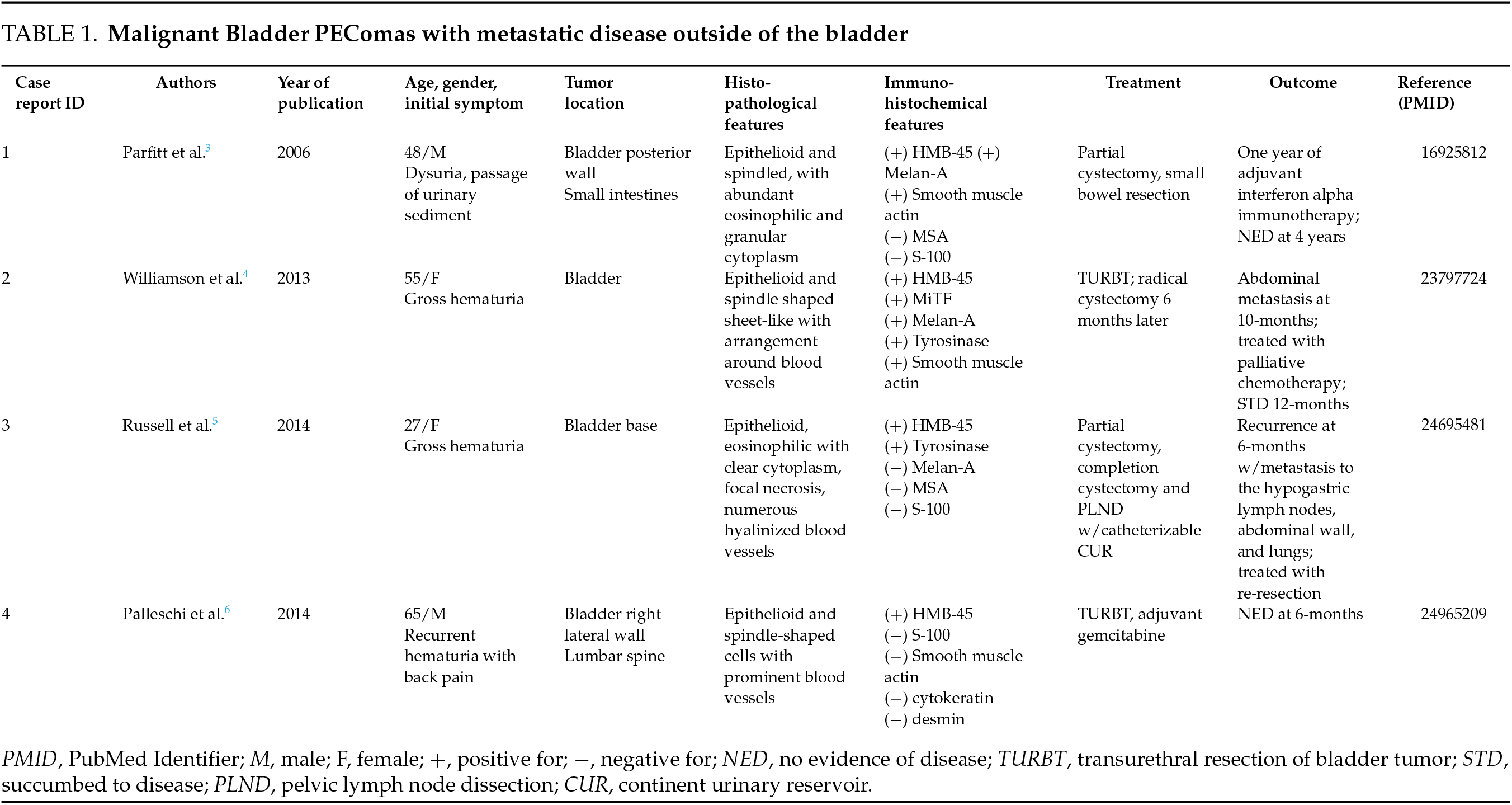

Bladder PEComas are typically benign in nature and indolent in their growth. However, there are a few reported cases in which bladder PEComas were found to be malignant and metastatic (Table 1).3–6 The current challenge involving PEComas is their management, as surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment for aggressive cases. Chemotherapy and immunotherapy have shown mixed results in treating metastatic, unresectable tumors.3–7 Due to the rarity of the disease and even smaller subset of metastatic cases, very few patients and follow-ups have been documented. Hence, it is difficult to characterize the prognosis of bladder PEComas as less than 50 cases have been reported so far in the medical literature. In this report, we present the case of a 37-year-old male who presented to the emergency department in clot retention and was found to have a pelvic PEComa with bladder invasion.

The patient in question is a 37-year-old male with a history of human immunodeficiency virus with an undetectable viral load, latent tuberculosis treated previously with nine months of isoniazid and pyridoxine therapy, syphilis, obesity status post gastric bypass, depression, and anxiety. The patient was initially evaluated at an outside hospital (OSH) where a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 9 cm pelvic mass (Figure 1). A biopsy was conducted, which was consistent with a PEComa, with no evidence of a malignant component at that time. He was admitted to the OSH around one month later with hematuria and found to be in clot retention. This was resolved with Foley catheter placement and continuous bladder irrigation (CBI). The patient discharged to home on hospital day 5. The patient presented to our tertiary referral care center five days later following his discharge, and less than 12 h after his Foley catheter had been removed, where he was again found to be in clot retention.

FIGURE 1. Complex, heterogenous pelvic mass measuring 9.2 cm × 8.4 cm × 9.5 cm as shown on MRI of the pelvis in axial (left pane), coronal (middle pane), and sagittal (right pane) views

A 3-way 20-French urinary catheter was replaced and hand irrigated, with return of clot material. The patient was restarted on CBI overnight and taken to the operating room the next morning for a clot evacuation and transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT). Approximately 1 L of clot material was evacuated from the bladder. Diagnostic cystoscopy demonstrated most of the bladder dome to be replaced by an ulcerated, necrotic mass. His trigone, bilateral ureteral orifices, and lateral bladder walls were spared. Samples of the mass were obtained via TURBT and sent for pathological evaluation. Postoperatively, the patient was resumed on CBI and initiated on an aggressive regimen to control bladder spasms.

Following the operation, the medical oncology and colorectal surgery teams were consulted. While awaiting the pathology results, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan was obtained to evaluate for further pelvic invasion and distant metastasis. This study demonstrated a “large heterogenous peripherally hypermetabolic pelvic mass invading the posterior wall of the urinary bladder and partially compressing the rectosigmoid colon and right internal iliac vasculature without hypermetabolic nodal or distal metastasis” (Figure 2). Pathology was returned 7 days later, confirming the diagnosis of a PEComa as had been reported by the OSH. However, in this pathological analysis, the PEComa was reported to be malignant. Per the pathology report, “biopsy of the mass shows a malignant spindle and epithelioid neoplasm involving the wall of the bladder. The tumor cells have a myoid appearance with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm as well as areas of clear cell change. Cytologic atypia is present along with focal hemorrhage and notable areas of necrosis. Mitotic activity is markedly increased.” Notably, slides from the previous mass biopsy provided from the OSH and read at our hospital did not report any malignancy in that sample.

FIGURE 2. Heterogenous, peripherally hypermetabolic pelvic mass shown on PET scan taken during the patient’s index admission

Following the pathological analysis and PET scan, multiple interdisciplinary discussions were held at tumor board meetings to collaborate on the best course of action for the patient. These discussions focused on: the chance of a curative operation; the possibility of an organ sparing operation vs. the need for radical cystectomy; the best urinary diversion for the patient if radical cystectomy was indicated; and whether preoperative radiation therapy had any role. After these meetings and extensive discussions with the patient, the patient elected to proceed with a partial cystectomy with a pelvic mass excision. If this was not possible based upon intraoperative findings, the patient elected for a radical cystectomy with an ileal conduit creation. No preoperative chemotherapy or radiation therapy was pursued.

The patient was taken to the operating room on hospital day 12 for definitive surgical management. Diagnostic laparoscopy revealed a friable pelvic mass. Peritoneal inspection revealed what visually appeared to be tumor implants. A portion of this anterior peritoneal tissue was sent for urgent frozen inspection, which was returned positive for malignancy. With confirmed metastatic disease, the goal of the operation shifted from curative to palliative. Given the friable nature of the tumor, the decision was made to convert to an open procedure to give better control and limit any further peritoneal spread. An open pelvic mass excision (final pathology in Figure 3) and partial cystectomy was performed. The colorectal surgery team assisted intraoperatively and ruled out rectal and distal sigmoid colonic involvement. The rest of the surgery was performed without major complication.

FIGURE 3. (A–F) Clinicopathologic Features of Malignant PEComa, (A): On gross examination, the tumor reveals a gray-white cut surface with areas of degeneration and focal hemorrhage (B): On histopathology, low-power magnification reveals a lesion composed of sheets of spindle cells (H&E 10×), (C): Other areas display epithelioid morphology (H&E 20×), (D): High-power magnification shows frequent mitotic figures (H&E 40×), (E,F): On immunohistochemistry, there is diffuse expression of smooth muscle actin and variable expression of Cathepsin-K (10×)

The patient progressed well postoperatively. He was placed on an aggressive regimen to limit the extent of his bladder spasms given the resection of approximately one-third of his native bladder as part of the pelvic mass excision. He was placed on CBI postoperatively, which was gradually titrated down until it was clamped on postoperative day 5. He was discharged to home on postoperative day 7 with a 3-way Foley catheter in place in case additional hand irrigation needed to take place at home. At the time of discharge, the patient had follow-up plans in place with both the urology and oncology services.

Further treatment options with the oncology team were planned to involve upfront systemic chemotherapy vs. further tumor excision with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Genomic profiling was conducted in order to determine tumor genetic markers to help guide this decision and therapy choice. A comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) test including both DNA and RNA was utilized, which reported on both biomarker findings and genomic findings. This testing revealed the bladder PEComa to have microsatellite stability and a tumor mutational burden of 5 mutations per megabase. It also revealed alterations in platelet derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRB) gene, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) gene, and loss of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A and 2B (CDKN2A/B). While not studied specifically in bladder PEComas, the testing indicated a possible therapeutic benefit to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib.

Unfortunately, the patient was readmitted to the hospital with back pain, flank pain, and low-grade fevers before this information could be utilized to guide the patient’s treatment. This occurred one-month after his initial discharge from our tertiary care center. The patient proceeded to have a complicated hospital course. He required bilateral nephrostomy tube placement, and later developed acute hypoxic respiratory failure (AHRF) requiring intubation. The patient was subsequently extubated but continued to decline from an overall functional status. After multiple discussions involving the patient’s goals of care, he was eventually transitioned to a comfort care status. The patient passed away 10-weeks after his partial cystectomy.

PEComas represent an uncommon malignancy of the genitourinary tract. Their infrequent presentation within the urinary bladder has previously been reported to be largely benign in nature and responsive to simple resection. The above patient’s presentation is exceptionally rare given the metastatic nature of the lesion and the resultant patient mortality. We present this case in hopes of furthering the literature for other urologic oncologists faced with this neoplasm.

Our initial approach to this patient was guided by both the OSH pathology, MRI and PET imaging, and the results of the TURBT. The tumor was reportedly benign, and preliminary imaging appeared to indicate solid tumor confinement to the bladder and pelvis. While awaiting the results of the TURBT pathology, a PET scan was still obtained to assess for metastasis. As noted above, the PET scan was “without hypermetabolic nodal or distal metastasis”. The pathology results of the TURBT returned showing some malignant potential. Given the apparent lack of metastasis and limited data reporting benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy, a tumor board discussion between urology, oncology, and radiology decided that pursuing a partial cystectomy was prudent. The patient agreed with this plan, but also was made aware of the possible need to convert to a radical cystectomy with urinary diversion if indicated intraoperatively. The speckled appearance of the peritoneum on diagnostic laparoscopy was apparent shortly after entering the abdomen, and metastasis was confirmed shortly thereafter on frozen inspection. In postoperative discussions, the patient was very interested in pursuing systemic therapy, and elected to proceed with genomic testing.

The genomic profiling test evaluated more than 400 DNA-sequenced genes and more than 250 RNA-sequenced genes. Results were classified into biomarker and genomic findings. From a biomarker standpoint, the genomic testing revealed the patient’s PEComa to have microsatellite stability. Tumors with microsatellite stability have been shown to be less responsive to PD−1 immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab as compared to microsatellite unstable tumors. The genomic testing also showed a tumor mutational burden (TMB) of 5 mutations per megabase (i.e., 5 Muts/Mb) of interrogated genomic sequence. PEComas have previously been reported to have a median TMB of 1.6 Muts/Mb.8 Studies have demonstrated a more favorable response to PD−1 immune checkpoint inhibitors with a TMB > 10.9 As such, no possible therapies were demonstrated from the biomarker analysis of the bladder PEComa.

From a genomics standpoint, the testing identified alterations in the platelet derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRB) gene, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) gene, and loss of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A and 2B (CDKN2A/B). While not studied in bladder PEComas, PDGFRB gene mutations have shown a response to the small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib in studies of other genitourinary tumors such as renal cell carcinoma. As such, the CGP testing recommended possible therapy with this agent. Unfortunately, progression of the patient’s disease and decline in overall clinical status prevented him from trialing this therapy.

The current literature on malignant bladder PEComas with metastatic disease is limited given the rarity of this disease process. Russell et al.5 compared nine different cases of bladder PEComas using the classification schemata proposed by Folpe et al.2 High risk features of PEComas include size >5 cm, infiltrative growth, high nuclear grade (>2) and cellularity, mitotic rate ≥ 1/50 HPF, evidence of necrosis, and evidence of vascular invasion. PEComas with <2 high risk features are considered benign; those with ≥2 high risk features are considered malignant. PEComas ≥ 5 cm with no other high risk features or those with nuclear pleomorphism or multinucleated giant cellsa are of uncertain malignant potential.2,5 Our review of the literature identified 4 cases of malignant bladder PEComas with metastatic disease (Table 1). Parfitt et al. described a case of bladder PEComas with invasion into the small intestines. Interestingly, the tumor described was <5 cm in size and did not share many of the high-risk features described by Folpe et al. The patient was treated with partial cystectomy and a year-long course of interferon alpha. The patient remained disease free at 4 years of follow-up.3 Williamson et al. reported a case initially treated with transurethral resection (TUR), followed by radical cystectomy 6-months later. At 10-months post-TUR, surveillance imaging revealed disease recurrence with abdominal metastasis. The patient underwent salvage chemotherapy, but died 12-months post-TUR.4 Russell et al. reported the case of a 27-year-old female who initially underwent partial cystectomy, later followed by completion cystectomy, pelvic lymph node dissection, and creation of a catheterizable continent urinary reservoir. The patient had disease recurrence at 6-months with metastases to the hypogastric lymph nodes, anterior abdominal wall, and lungs, which were reportedly treated with re-resection of these sites but further follow-up was not reported.5 Palleschi et al. described a case in a 65-year-old male who presented with recurrent hematuria and back pain. The bladder lesion was treated with TUR, but follow-up PET imaging revealed concerning lesions in the lumbar spine and left iliac crest. The patient underwent a 4-week cycle of gemcitabine, and was reportedly disease free at 6-months, although confirmatory biopsy of the bony lesions was not reported.6

The increasingly mainstream application of CGP is providing more therapeutic guidance for cancer patients and their physicians, even in patients with exceptionally rare tumors like the metastatic bladder PEComa described above. Prior adjunctive therapies for the treatment of bladder PEComas have included chemotherapy and immunotherapy in conjunction with surgical resection.3,4,6 Again, given the rarity of these reports, the efficacy of these adjunctive therapies cannot be statistically validated. Nevertheless, the prospective use of CGP will hopefully elucidate more targeted therapies for this subset of patients, and provide urologists and oncologists adjunctive treatments when surgical resection alone is not enough.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The first draft of the manuscript was written by Peter J. Arnold and Mabel Spio. Reem Youssef provided gross and microscopic image collection and interpretation. Peter J. Arnold, Mabel Spio, Reem Youssef, Carina Dehner and Kevin Rice provided revisions on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The Indiana University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board exempt status was granted for the conduct of the study (IRB #23221) prior to any data collection or documentation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Masterson TA, Cary KC, Foster RS. Retroperitoneal tumors. In: Campbell A, Walsh P, Wein A, editors. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th edition. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Elsevier, 2023. p. 2234. [Google Scholar]

2. Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29(12):1558–1575. [Google Scholar]

3. Parfitt JR, Bella AJ, Wehrli BM, Izawa JI. Primary PEComa of the bladder treated with primary excision and adjuvant interferon-alpha immunotherapy: a case report. BMC Urol 2006;6(1):20. [Google Scholar]

4. Williamson SR, Bunde PJ, Montironi R et al. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) of the urinary bladder with TFE3 gene rearrangement: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37(10):1619–1626. [Google Scholar]

5. Russell CM, Buethe DD, Dickinson S, Sexton WJ. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the urinary bladder associated with Xp11 translocation. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2014 Winter;44(1):91–98. [Google Scholar]

6. Palleschi G, Pastore AL, Evangelista S et al. Bone metastases from bladder perivascular epithelioid cell tumor—an unusual localization of a rare tumor: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014;8(1):227. [Google Scholar]

7. Sanfilippo R, Jones RL, Blay JY et al. Role of chemotherapy, VEGFR inhibitors, and mTOR inhibitors in advanced perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas). Clin Cancer Res 2019;25(17):5295–5300. [Google Scholar]

8. Akumalla S, Madison R, Lin DI et al. Characterization of clinical cases of malignant PEComa via comprehensive genomic profiling of DNA and RNA. Oncology 2020;98(12):905–912. [Google Scholar]

9. Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21(10):1353–1365. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools